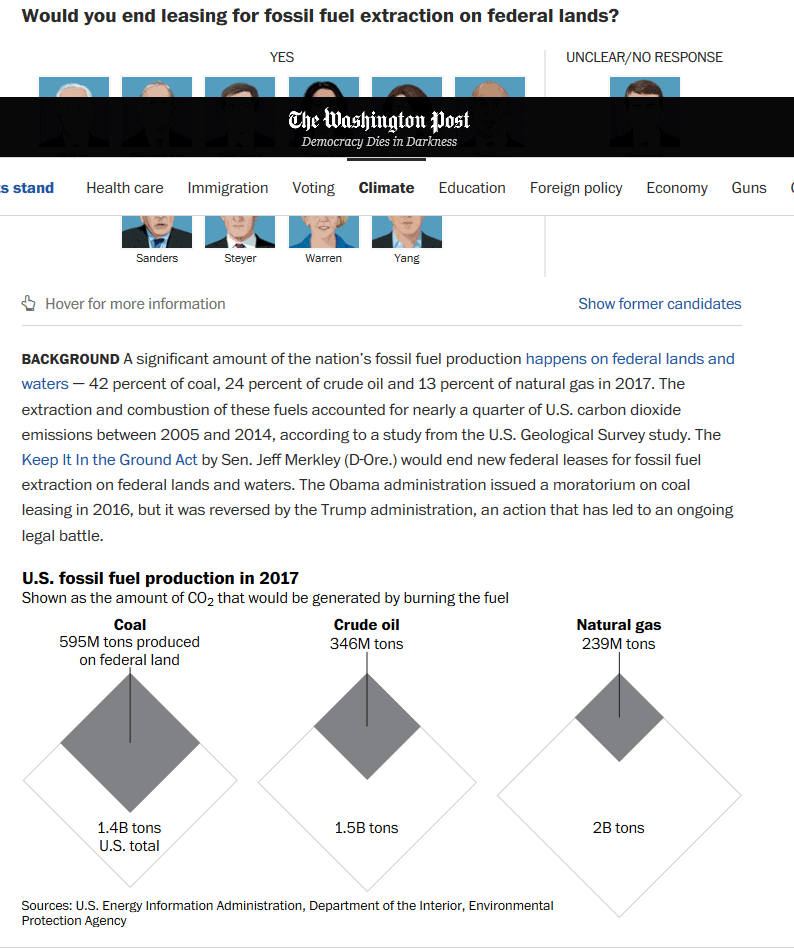

This post is intended to start an information source and discussion on where Democratic primary candidates stand on federal lands issues. The WaPo has a very useful section called “Where Democrats Stand”. Most of the time, federal lands issues would probably not show up, but the WaPo did ask a question “would you end leasing for fossil fuel extraction on federal lands?” Here’s the link. If others can find a handy place where candidates’ other federal lands policy positions can be found, or add to the WaPo findings, please post in the comments. Note: I believe that we can talk about candidates’ positions without saying mean things abouot them or each other.

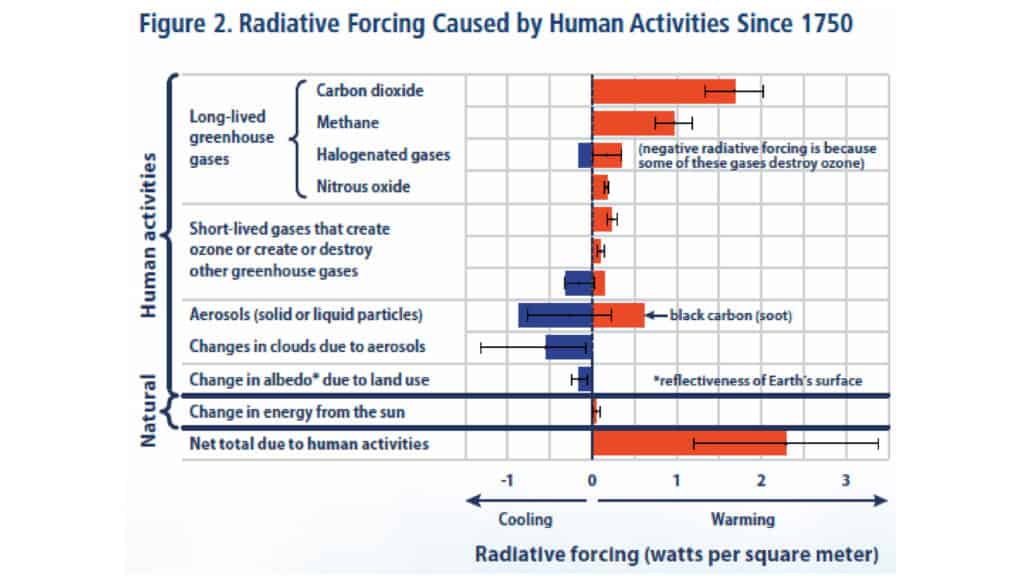

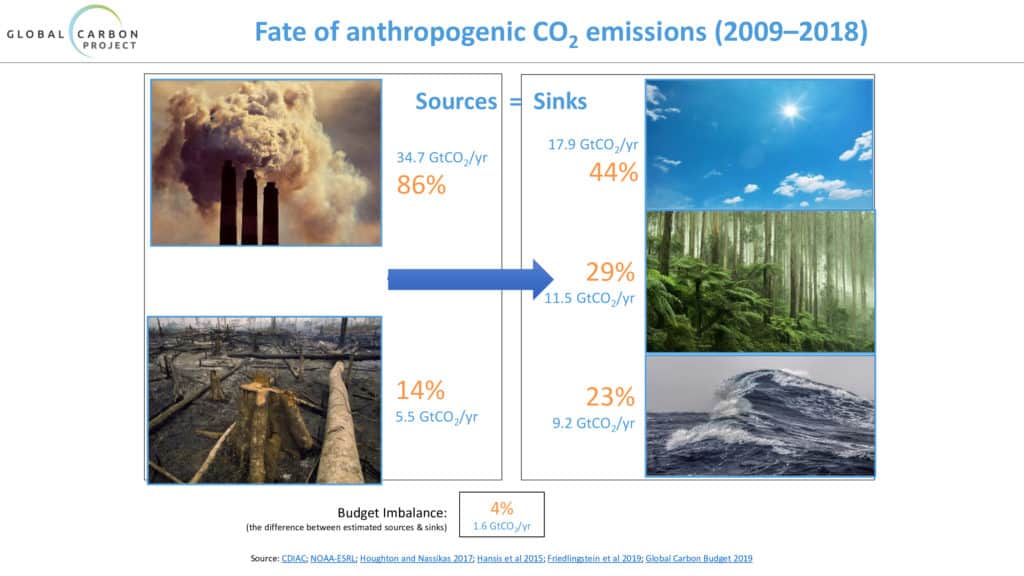

BACKGROUND A significant amount of the nation’s fossil fuel production happens on federal lands and waters — 42 percent of coal, 24 percent of crude oil and 13 percent of natural gas in 2017. The extraction and combustion of these fuels accounted for nearly a quarter of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions between 2005 and 2014, according to a study from the U.S. Geological Survey study. The Keep It In the Ground Act by Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) would end new federal leases for fossil fuel extraction on federal lands and waters. The Obama administration issued a moratorium on coal leasing in 2016, but it was reversed by the Trump administration, an action that has led to an ongoing legal battle.

Note that Senator Bennet, the only candidate from a state with substantial federal lands, did not respond. I did not check the WaPo’s figures, but they seem consistent with this CRS report.

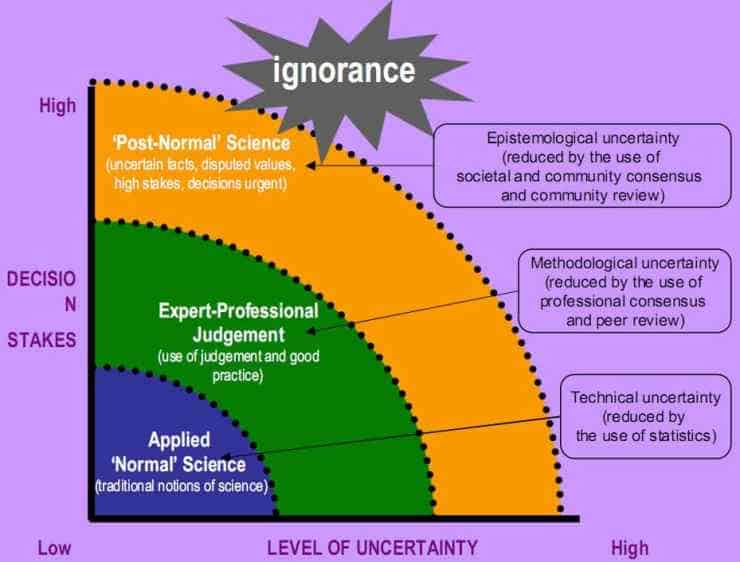

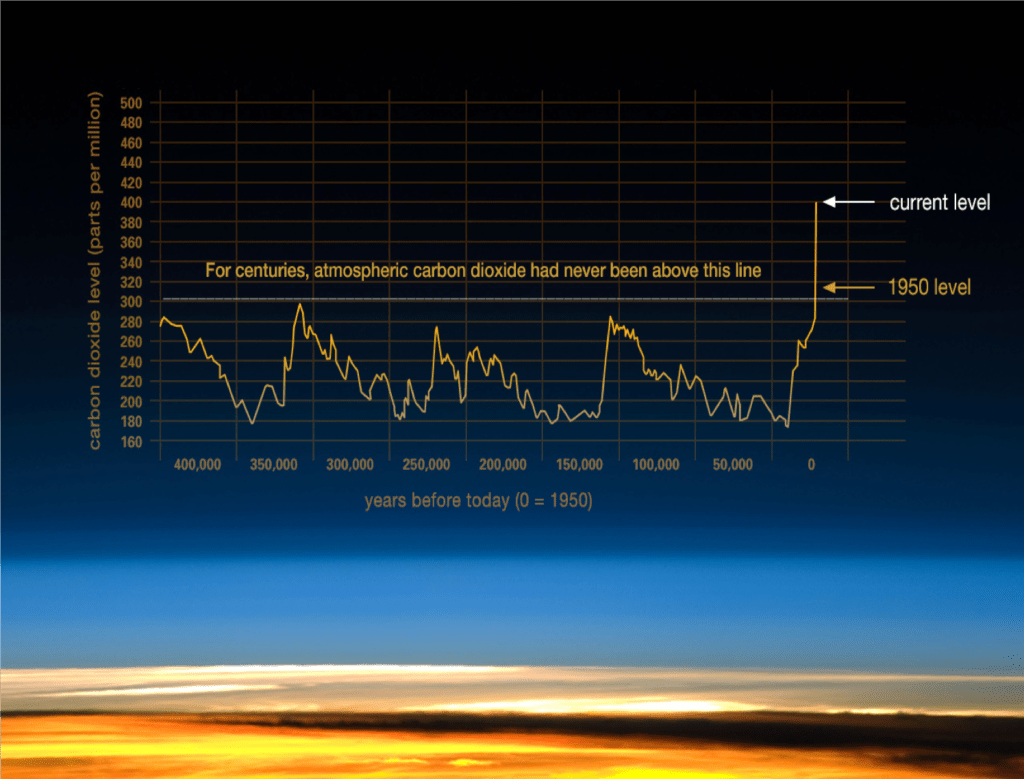

The argument seems to be that if we didn’t produce that coal, oil, and gas on federal land, the GHG’s would not be emitted. It seems to me that experience has shown that we would substitute from private land or import. Perhaps that would lead to increased prices (reduced supply) and therefore the amount of GHG’s emitted would thereby be reduced. However, the need to raise prices for essential heat, electricity and transportation fuel (having the pain felt by those with least discretionary income) to reduce demand doesn’t seem like big vote-getter, so it’s not clear to me exactly what the logic path is.

Biden says “banning new oil and gas permitting” but perhaps not coal? Not clear.

Bloomberg says “I will immediately end all new fossil fuel leases on federal land.”

Buttigieg “supports” ending new leases for fossil fuel extraction. Perhaps this is more realistic than “immediately ending” an activity that is provided for in statute.

Gabbard says “end the leasing of fossil fuel extraction on federal lands and watere.”

Klobuchar and Patrick also “support ending new leases.”

Sanders wants to keep everything in the ground, which includes federal lands.

Tom Steyer says “Keep publicly-owned oil, coal, and gas in the ground by stopping the expansion of fossil fuel leases and establishing a careful process to wind down federal onshore and offshore fossil fuel production.” This sounds a little different than just having new leases, but not sure. Also not sure you need a “careful process” to wind it down if you stop issuing leases.

Warren says “As president, I would issue an executive order on day one banning all new fossil fuel leases, including for drilling or fracking offshore and on public lands.”

Yang supports ending leasing for fossil fuel extraction on federal lands, his campaign told The Post.

Two candidates responded with specific goals for federal lands and renewable energy:

Bloomberg includes “expedite clean energy development in federal lands along with offshore wind.”

Warren pledges “to generate 10% of our overall electricity needs from renewable sources offshore or on public lands.”

Of course, ramping up clean energy on federal lands comes with environmental concerns as well.

There’s also a link to a fracking ban here. Here the candidates are more diverse. Perhaps Bennet has the most nuanced “I believe natural gas has a role to play” in transitioning to net-zero emissions “as long as it is developed in a way that protects the health of our communities” and Klobuchar, perhaps, the oddest “So as president in my first 100 days, I will review every fracking permit there is and decide which ones should be allowed to be continued and which ones are too dangerous.”