Here’s a press release from Western Watersheds Project about the Forest Service’s plans to eliminate a Black-Footed Ferret Recovery management area of over 50,000 acres on Wyoming’s Thunder Basin National Grassland via a Forest Plan amendment.

Yesterday, Jon Haber shared this account of the Coconino National Forest in Arizona amending a Forest Plan, which was just revised in 2018, to facilitate construction of a powerline.

That got me wondering: Can folks think of many examples where the U.S. Forest Service has amended a Forest Plan to strengthen protections for wildlife, clean water, old-growth forests, soils or biodiversity? If so, please do share these examples. Regardless, my gut feeling is that the number of times the Forest Service has amended a Forest Plan to weaken protections for wildlife, clean water, old-growth forests, soils or biodiversity would far outnumber them.

Here’s that Western Watersheds Project press release:

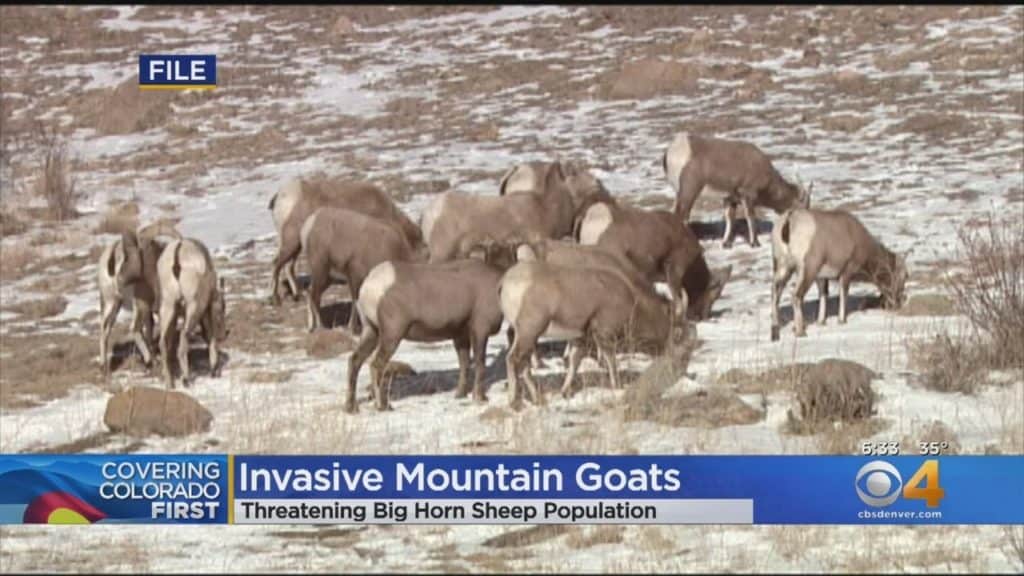

LARAMIE, Wyo. – Western Watersheds Project submitted formal comments today excoriating a Forest Service proposal to eliminate a Black-Footed Ferret Recovery management area of over 50,000 acres on Wyoming’s Thunder Basin National Grassland. The Forest Service’s plan amendment increases the poisoning and shooting of native prairie dogs, upon which ferrets depend for their survival, an action driven by livestock lobby concerns that prairie dogs compete for vegetation with privately-owned cattle on these public lands.

“The Thunder Basin is one of the rare large expanses of public land where black-footed ferrets could be reintroduced on the High Plains,” said Erik Molvar, a wildlife biologist and Executive Director with Western Watersheds Project. “The Forest Service has an obligation to recover both prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets to their natural and healthy populations here, irrespective of livestock industry profits.”

The black-tailed prairie dog is designated as a Sensitive Species by the Forest Service. Ecologically, it is considered a “keystone species” holding grasslands ecosystems together, and it is critical to the survival of many other rare species of wildlife, from burrowing owls to swift foxes to mountain plovers. According to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, black-tailed prairie dogs are down to one-one-hundredth of one percent of their original occupied habitat in Wyoming.

The original Grasslands Plan, completed in 2002, limited prairie dog poisoning to areas immediately adjacent to homes and cemeteries, and protected prairie dogs from sport shooting in the Black-footed Ferret Recovery zone. Thunder Basin ranchers, dissatisfied with the limitations governing prairie dog killing on public lands, pressed for weaker protections and more loopholes, and succeeded in dominating a collaborative process that wound up expanding prairie dog poisoning to Forest Service lands along private land boundaries. The new plan amendment expands poisoning and recreational shooting further still.

“Ranchers shouldn’t be able to rent public lands for private livestock grazing if they can’t coexist with the native wildlife, prairie dogs included,” said Molvar. “The idea that a federal agency wants to authorize the poisoning native wildlife in order to keep them off neighboring private lands – where they are also native – effectively imprisons wildlife on public lands and blocks them from repopulating their original habitats elsewhere.”

The Thunder Basin National Grassland encompasses lands that are the traditional lands of the Cheyenne, Crow, and Lakota peoples.

###