Let’s talk about framing issues- described in the Wikipedia entry here.

Let’s talk about framing issues- described in the Wikipedia entry here.

In social theory, framing is a schema of interpretation, a collection of anecdotes and stereotypes, that individuals rely on to understand and respond to events.[2] In other words, people build a series of mental “filters” through biological and cultural influences. They then use these filters to make sense of the world. The choices they then make are influenced by their creation of a frame.

Framing is also a key component of sociology, the study of social interaction among humans. Framing is an integral part of conveying and processing data on a daily basis. Successful framing techniques can be used to reduce the ambiguity of intangible topics by contextualizing the information in such a way that recipients can connect to what they already know.

Framing involves social construction of a social phenomenon – by mass media sources, political or social movements, political leaders, or other actors and organizations. Participation in a language community necessarily influences an individual’s perception of the meanings attributed to words or phrases. Politically, the language communities of advertising, religion, and mass media are highly contested, whereas framing in less-sharply defended language communities might evolve imperceptibly and organically over cultural time frames, with fewer overt modes of disputation.

Two additions to the Wikipedia entry. Scientific communities and disciplines specifically also do framing (“other actors”). But what the entry isses is that individuals are each entitled to her or his own framing of any issue. We can each drop our pin and define the problem in our own way. But only some of us have access to research funding to investigate and publish on a particular topic. So when folks say “the science says, so we should..,” it can be another case of “authority by privilege,” as people without access to research funding to study questions within their framing, remain unheard. Different framings most commonly lead us into talking past each other. Let’s look at an example.

Since the 80’s (at least) folks have been talking and studying about the pros and cons of harvesting trees in Western (and to a lesser degree, Central and Eastern Oregon). If you’re in Western Oregon, the framing may be “should timber harvest occur? If so, what practices will sustain the (owls, fish), minimize carbon loss, be resilient to climate change, and so on?”

But what if the pin is dropped instead somewhere in the Front Range of Colorado, which is a wood products sink, not source, with expanding residential and commercial development? If we were to look for environmentally protective things to do (to use less wood), we could try (1) not allowing people to move here, (2) changing building codes to allow only multi-family housing (from the lumber and heating and cooling efficiency perspective), plus a variety of other planning and development regulation options.

Let’s imagine our fully-funded Front Range Sustainable Development Research Center. First we’d gather stakeholders, including representatives of state and county governments, who would decide what questions to be addressed. Perhaps we’d do a study comparing wood and other construction materials in terms of their environmental costs and benefits (or at least try to figure out why existing studies disagree). Environmental impact would include emissions from transport to us, what would happen if trees weren’t cut in terms of carbon, including the social likelihood of other uses of forested areas (say the Southern US) or possibly burning up (with more fires due to climate change), as well as all the other considerations.

But all that is from the environmental perspective, which is not the only one. There are also possible social costs, due to (maybe) higher prices from Canada (cue the various incarnations of the Softwood Lumber DisAgreements). Plus, there are tax and feeding families advantages to producing products in our own country. Our Center would do research on all these aspects of wood product sources and uses, as guided by the stakeholder group.

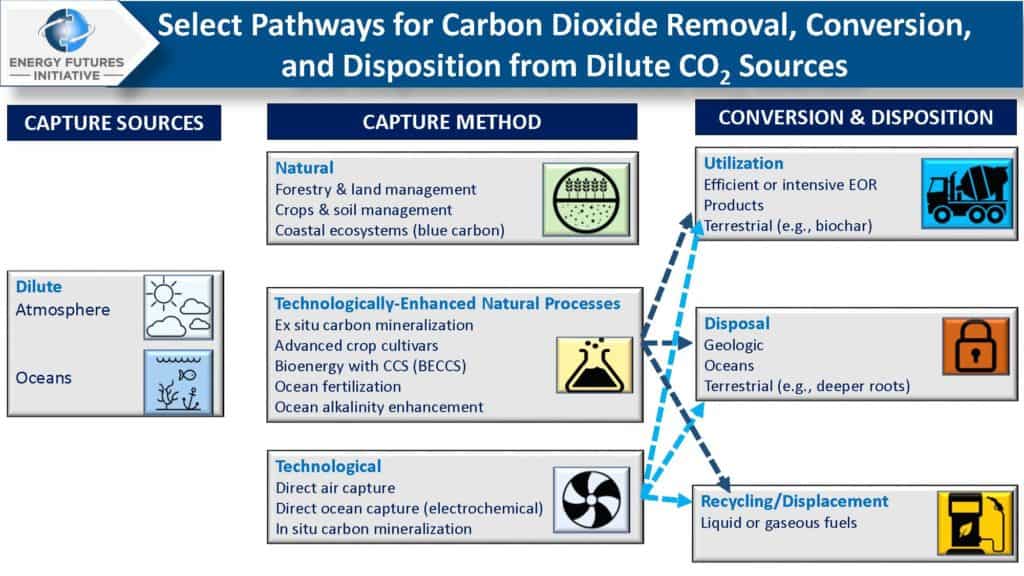

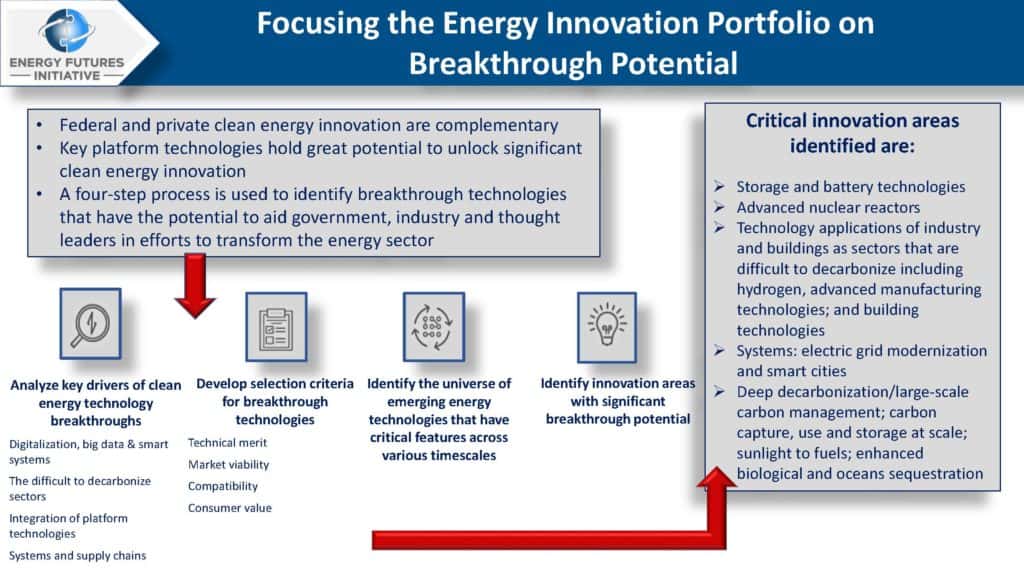

And we can’t leave out the conditional nature of any scientific knowledge. So the folks working on putting CO2 into concrete might change all these calculations if/when they scale up.

Holy Pseudotsuga! There are a great many things that could be studied, from a variety of perspectives and across a wide range of disciplines! And whether your state or county is a source or a sink might well affect the design of research. And while all these studies will help inform policy, none should determine policy. After all, perhaps the most environmentally preferable one would be to keep people out. But then where would they go, and what would be the impacts there?

So where do you drop your pin or frame the issue?And what would your research program look like?

One more thing you may have noticed. It’s fairly easy to calculate some impacts, but at some point you are making guesses about what people and technology are going to do or not do. Is it better for decision makers and the public to openly discuss those guesses (say, scenario planning) or to put guesses into models where they lose the information on their uncertainty?