(This is from Steve Wilent) Smokey Wire folks, I received an op-ed from Rob Freres, president of Freres Lumber Co. in Oregon, in response to our discussion. It’s long, but worth a read — and a comment or two. A friend had forwarded an email with part of our discussion to Mr. Freres. I invited him to join us and participate in this and other posts. I hope he’ll do so. The more viewpoints the better.

Let’s Take Another Look at John Talberth’s Street Roots Interview

By Rob Freres

Matthew Koehler recently shared a Street Roots News interview with the Center for Sustainable Economy’s John Talberth. The interview reveals the core arguments coming from the fringe of the environmental movement, that is: 1) nobody should make a dime in federal forest management; 2) new taxes and policies are needed to make private forest management unprofitable; and 3) taxpayer subsidies will be necessary once public and private forest management both become unprofitable.

Forestry is a big business. So is environmentalism. The environmental activist industry supports hundreds of well-funded and well-staffed organizations. These self-described “think tanks” and “watchdogs” are subsidized through preferential tax policies, and supported by deep pocketed foundations and millionaire “do-gooders,” and tax-sheltering benefactors – not to mention outdoor retailers that manufacture products overseas with non-renewable materials and questionable labor practices. Federal forest management alone has created a cottage industry as environmental litigation transfers millions of tax dollars to groups through the Equal Access to Justice Act. With so much competition in the industry, it’s hard to blame Talberth for producing provocative “research” that seeks attention, stirs controversy, and attracts funding.

Savvy environmentalists like Talberth understand Americans are wary of corporations, and are now especially sensitive to the influence of foreign actors in domestic affairs. That’s why Talberth expresses alarm over the ownership of industrial forestlands, and in particular the “growing share” of “foreign investors and foreign companies.” Talberth cites a USDA Farm Service Agency report indicating 555,134 forested acres in Oregon are foreign-held, though the report doesn’t delineate how much of that land is used for industrial timber production. To put this number in perspective, that’s just five percent of the 9.4 million acres of Oregon forests that are privately managed, and just a tenth of one percent of Oregon’s total forested land base.

The federal government owns 60 percent of Oregon’s forested land base and pays no property taxes. Large private landowners own 22 percent of the forests and pay a variety of taxes, so do the over 100,000 small private land owners who own and manage their own forests.

Talberth also understands Americans are increasingly concerned about climate change. He and others are aggressively pushing a narrative that “big timber” is a top carbon emitter, even surpassing the transportation sector. Every article and interview pushing this narrative cites research that has long been picked apart. Such agenda-driven science, perhaps more accurately described as “political science,” often doesn’t account for 1) the carbon that is stored in manufactured wood products (such as the wood in your home); 2) the replanting of trees after harvest (a legal requirement in the state of Oregon where more trees are planted than harvested); 3) the rate of carbon sequestration of young forests (a point that was intentionally and completely neglected by the infamous Bev Law “study”); and most commonly 4) “leakage,” where reduced timber harvests in the United States would simply be replaced by timber harvests in Canada, Asia, South American, and elsewhere.

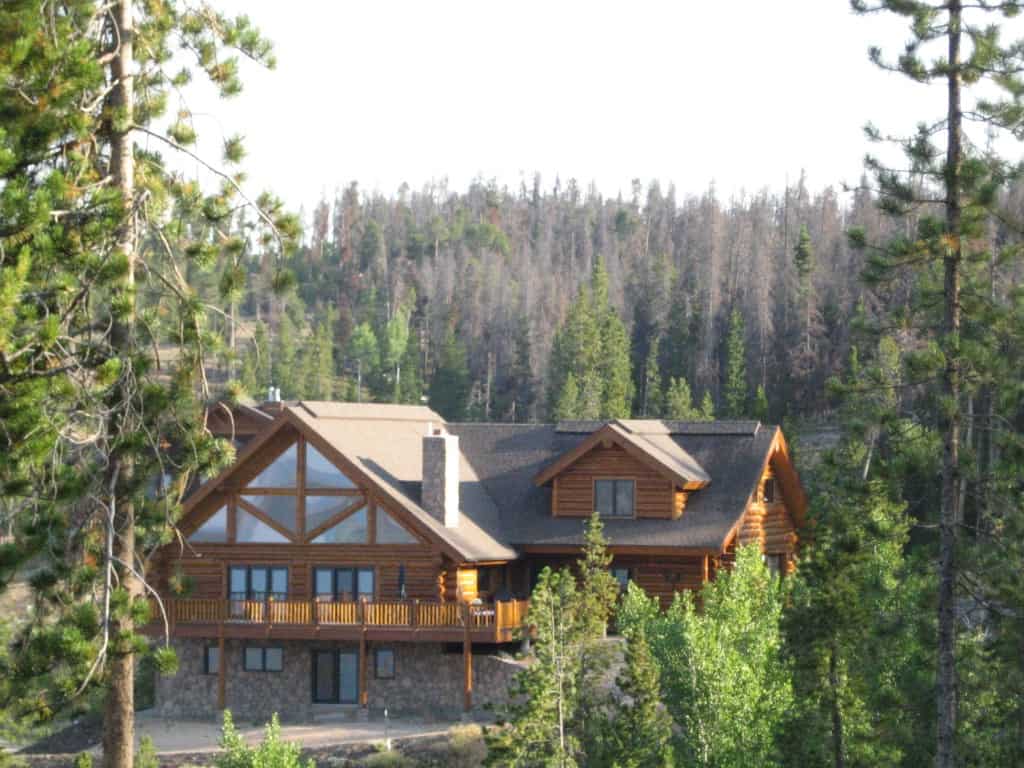

Talberth, an economist by training, is familiar – or at least should be familiar – with the concept of elasticity of supply and demand. “Stopping” timber harvests on federal lands does not diminish worldwide demand for wood products. It would only change where the wood comes from. And there is never any recognition of the carbon emissions from catastrophic wildfires that often burn through unmanaged, overstocked and insect-infested stands on federally-owned forests. There are now national forests in the Rocky Mountain states that are carbon emitters exactly because management has been neglected and forest mortality exceeds forest growth.

Who really benefits from Mr. Talberth’s anti-forestry agenda? Aside from environmental organizations, the prime benefactors are the concrete and steel industries that emit far more carbon emissions than the forest sector. Foreign actors would only benefit from the transfer of America’s technological, engineering, science, and efficiency advantages – and the manufacturing and domestic jobs they support – to countries with less restrictive conservation laws and regulations. Once logs are no longer exported from North America, the fiber will be logged in other countries, such as the Amazon rainforest where loggers do not operate under strict regulations and environmental safeguards. Some members of Congress have sought to bring attention to the influence of foreign actors on the environmental movement itself. Maybe they’re on to something.

Since the 1990s “zero cut” activists have also pushed studies questioning “logging subsidies” on National Forest System lands. Talberth’s latest “report” doesn’t offer anything new and hasn’t gained much traction as Republicans and Democrats alike seek to accelerate forest management activities on federal lands. Just like agenda-driven studies on carbon emissions, it simply cherry picks data, and conveniently ignores variables relating to log markets and the economics of harvesting timber under the current process. In reality, federal timber purchasers have paid over $1.1 Billion for National Forest System timber since 2011, which by law is used to enhance resources on National Forest System lands, ensure reforestation, and provide safe ongoing access to fire suppression, recreational use, and future management. A portion of these logging revenues have also helped build and sustain rural communities and essential public services like law enforcement, education, and transportation for more than a century.

Talberth objects “to the very idea of using federal forest lands for private profit.” He must be referring to timber, because the recreation industry generates billions of dollars in profit off of utilizing these lands. Of course this statement ignores that fact that national forests, unlike national parks, were always intended to be managed for many purposes— timber, recreation, grazing, wildlife, fish and more. In some ways, environmental organizations have succeeded in making forestry on national forests unprofitable. This is especially true in the Southwest, where there is little forest infrastructure left to implement federal restoration projects that reduce wildfire risks, enhance wildlife habitat and protect watersheds. Just ask Arizona, which faces severe forest health and wildfire threats but does not have the infrastructure or workforce to complete the necessary work.

For an economist, Talberth betrays a misunderstanding of forest economics. He also misunderstands the science of forestry by proposing one-size-fits-all prescriptions, which make little sense across different forest types with different tree species. Variable density thinning may make sense in accomplishing specific objectives on certain forest types. But arbitrarily restricting the use of forestry tools and methods only leads to unintended consequences, in some cases the conversion of forests to shrublands, and in others the dominance of species that are less resilient to disturbances. Who would you trust to provide you with good information about how to manage a forest: a professionally trained and certified forester, or an economist and professional activist?

There are a lot of other things that Talberth gets wrong. For example, in attacking industrial landowners for receiving “tax exemptions” for road building and equipment, he misses the fact that most landowners do not own and operate their equipment. Logging and road-building equipment is most often owned and operated by small contractors, and accounting for tax depreciation often determines whether the contractor stays in operation or shuts down entirely. The tax policies that Talberth is proposing would only serve to destroy the small businesses that harvest and transport the wood, but maybe that’s his objective anyway.

Oregon’s system of taxing forestland and timber has evolved over the state’s history, and today is based on progressive property tax and forest practice laws that recognize different forest types, geographic areas, ownerships and forest management objectives. The “special rates” Talberth mentions were developed because past tax policies only served to encourage the liquidation of forest resources and the conversion of forest lands to other users. Private landowners also receive no compensation for the vast amounts of carbon stored on their lands, for opening their lands to the public for hunting and recreational purposes, or for often being the first line of defense for catastrophic wildfires exploding on public lands. Would Talberth suggest the public should pay landowners for these services and benefits?

HB 2659, which Talberth proposed in the Oregon legislature, likely failed to get traction because it would only increase the tax burden on small woodlands owner while repealing exemptions that promote the use of more modern and environmentally-sensitive logging equipment. Such poorly-written tax law would encourage lawsuits, create chaos in land taxation and assessment, impose costly red tape and- once again- encourage the liquidation and conversion of forest lands.

In the face of climate change, we should be pursuing solutions that maximize the carbon-sequestering potential of forests. We would agree with Talbert on that goal, but eliminating private enterprise from American forestry through illogical tax and regulatory policies would result in the opposite effect. America’s forest products industry is the green infrastructure that already supports thousands of “New Green Deal” type jobs that Mr. Talberth says he’s after. Attacking the forest products industry may be good for his business, but Talberth is targeting the very people who keep forests as forests, and are constantly innovating through modern science and technology to tackle some of our greatest social, economic, and environmental challenges. No amount of government subsidy can replace private enterprise.

Rob Freres is President of Freres Lumber Co., an Oregon-based premier wood products manufacturing company dedicated to bringing innovative, high-quality and environmentally sound wood products to market. The company’s operations support more than 450 employees.

As part of our tenth anniversary celebration, from now (the actual anniversary) for the next month, we are going to feature NCFP/TSW faves. Anyone can submit one and email me. All I ask is that you submit the link to the post, why it is your fave (or one of them), and why you think it’s still relevant today.

As part of our tenth anniversary celebration, from now (the actual anniversary) for the next month, we are going to feature NCFP/TSW faves. Anyone can submit one and email me. All I ask is that you submit the link to the post, why it is your fave (or one of them), and why you think it’s still relevant today.