In a small gesture for accuracy in media, I took the liberty of retitling Shellenberger’s November 4 Forbes piece for our TSW post. Here’s the link.

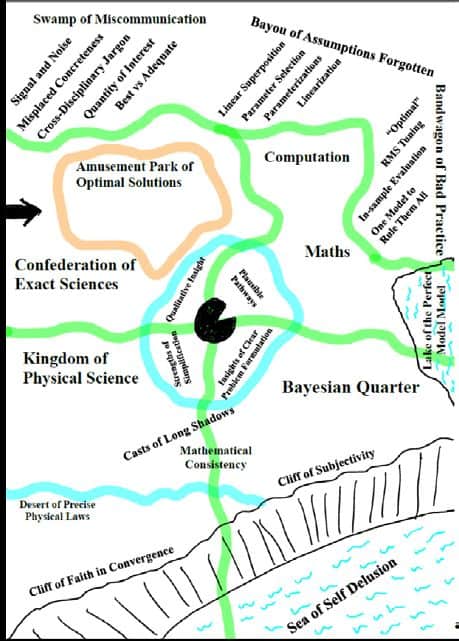

Let’s look at this article in light of what we discussed yesterday. Climate and wildfires both have their own sets of experts and a variety of disciplines, each of which having different approaches, values and priorities. I’m not saying that studying the results of climate modelling is entirely a Science Fad, but listen to Keeley here:

I asked Keeley if the media’s focus on climate change frustrated him.

“Oh, yes, very much,” he said, laughing. “Climate captures attention. I can even see it in the scientific literature. Some of our most high-profile journals will publish papers that I think are marginal. But because they find climate to be an important driver of some change, they give preference to them. It captures attention.

And the marginal ones are funded because.. climate change is cool (at least to “high-profile” journals, which have their own ideas of coolness). And who funds it? The US Government. Me, I would give bucks to folks for, say, physical models of fire behavior,(something that will help suppression folks today)rather than attempting to parse out the unknowable interlinkages of the past. But that’s just me, and the way the Science Biz currently operates, neither I nor you get a vote.

Note that the scientists quoted, (Keeley, North, and Safford) in this piece are all government scientists. Keeley and North are research scientists while Safford appears to be a Regional Ecologist (funded by the National Forests), so if we went by the paycheck method (are they funded by R&D?) Safford would have to get permission from public affairs, while Keeley and North would not. On the other hand, Safford has published peer-reviewed papers, so perhaps he should not have to ask permission? Even with permission requirements, though, they seem able to provide their expertise to the press.

Keeley talks about the fact that shrubland and forest fires are different beasts, and sometimes get lumped together in coverage. Below is an interesting excerpt on the climate question.

Keeley published a paper last year that found that all ignition sources of fires had declined except for powerlines.

“Since the year 2000 there’ve been a half-million acres burned due to powerline-ignited fires, which is five times more than we saw in the previous 20 years,” he said.

“Some people would say, ‘Well, that’s associated with climate change.’ But there’s no relationship between climate and these big fire events.”

What then is driving the increase in fires?

“If you recognize that 100% of these [shrubland] fires are started by people, and you add 6 million people [since 2000], that’s a good explanation for why we’re getting more and more of these fires,” said Keeley.

What about the Sierras?

“If you look at the period from 1910 – 1960,” said Keeley, “precipitation is the climate parameter most tied to fires. But since 1960, precipitation has been replaced by temperature, so in the last 50 years, spring and summer and temperatures will explain 50% of the variation from one year to the next. So temperature is important.”

Isn’t that also during the period when the wood fuel was allowed to build due to suppression of forest fires?

“Exactly,” said Keeley. “Fuel is one of the confounding factors. It’s the problem in some of the reports done by climatologists who understand climate but don’t necessarily understand the subtleties related to fires.”

So, would we have such hot fires in the Sierras had we not allowed fuel to build-up over the last century?

“That’s a very good question,” said Keeley. “Maybe you wouldn’t.”

He said it was something he might look at. “We have some selected watersheds in the Sierra Nevadas where there have been regular fires. Maybe the next paper we’ll pull out the watersheds that have not had fuel accumulation and look at the climate fire relationship and see if it changes.”

I asked Keeley what he thought of the Twitter spat between Gov. Newsom and President Trump.

Sharon’s note: I don’t know Keeley, but I thought he handled this very well, considering it’s not really a question about his research. The above italics are mine.

“I don’t think the president is wrong about the need to better manage,” said Keeley. “I don’t know if you want to call it ‘mismanaged’ but they’ve been managed in a way that has allowed the fire problem to get worse.”

What’s true of California fires appears true for fires in the rest of the US. In 2017, Keeley and a team of scientists modeled 37 different regions across the US and found “humans may not only influence fire regimes but their presence can actually override, or swamp out, the effects of climate.” Of the 10 variables, the scientists explored, “none were as significantly significant… as the anthropogenic variables.”

It’s encouraging to think that research shows that fire suppression has an big impact on fires. Otherwise, we’d have to give it up because fire suppression isn’t “based on science” 😉