As last time, I am just copying the cover email summaries provided by the Forest Service and providing the links to the supporting documents. However, August 28 there were no supporting documents (including the more detailed summary document) they usually provide. Also, apparently there was no weekly summary at all for September 4.

AUGUST 28

Forest Service Summaries: None

Court Decisions: Nothing to report

Litigation Update: Nothing to report

New Cases:

Forest Management | Region 1

WildEarth Guardians and Western Watersheds Project v. Chip Weber et al. (19-0056, D. Mont.) Region 1— On August 8, 2019, plaintiffs filed an amended complaint in the District Court of Montana against the Forest Service concerning the Forest Service’s decision finalizing the 2018 revision to the Flathead National Forest Land Management Plan (revised Forest Plan) on the Flathead National Forest (FNF). The plaintiffs’ amended complaint incorporates the Endangered Species Act (ESA) – 16 USC 1536 and Administrative Procedure Act (APA) 5 USC 706(2)(A) – regarding section 7 consultation with US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), including consultation regarding winter motorized use designations.

BLOGGER’S NOTE: The amended complaint was actually attached to the previous weekly summary and may be found here: WildEarthGuardians_v_Weber_19-56_amended_19-056_8-8-2019

Forest Management | Region 1

Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council v. Leanne Marten, et al. (19-00102, D. Mont.) Region 1— On August 26, 2019, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint in the District Court of Montana regarding the Decision Memorandum (DM) and 2014 Farm Bill Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA)Categorical Exclusion (CE) for the Willow Creek Vegetation Management Project (Project) on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest (HLCNF). Plaintiffs allege the decision violates the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Recreation | Region 1

Yaak Valley Forest Council v. Sonny Perdue et al. (19-143, D. Montana) – Region 1. On August 23, 2019, Plaintiff filed suit in the District Court of Montana against the Forest Service (FS) regarding use of the Pacific Northwest Trail (PNT) through the Yaak Valley within the Kootenai National Forest (KNF). Plaintiff alleges the FS violated the National Trails System Act (NTSA), Administrative Procedures Act (APA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), and the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

(An article on this lawsuit may be found here.)

Notice of Intent:

Transportation | Region 1

NOI (dated August 9, 2019 and received August 13, 2019) by Alliance for the Wild Rockies (AWR) alleging the Forest Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) violated the Endangered Species Act (ESA) requirements pertaining to the Hanna Flats Project on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest (IPNF) — Region 1. The AWR alleges the Forest Service failed to demonstrate compliance with the IPNF Forest Plan’s 2015 Access Amendment’s baseline total and open road miles requirements.

Natural Resource Management Decisions Involving Other Agencies: Nothing to report

SEPTEMBER 11

Forest Service summaries: 2019_09_11_Litigation Weekly_Email

Court Decisions: Nothing to report

Litigation Update: Nothing to report

New Cases:

Forest Management | Region 1

00001_Alliance for the Wild Rockies v Jeannie Higgins_Region 1

Alliance for the Wild Rockies v. Jeannie Higgins et al. (19-0332, D. Idaho) Region 1— On August 29, 2019 the plaintiff filed a complaint in the District Court of Idaho against the Forest Service regarding the Hanna Flats Good Neighbor Project on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest (IPNF). The plaintiff claims the Forest Service failed to demonstrate compliance with the IPNF Forest Plan 2015 Access Amendment (baseline total and open road miles requirements) in violation of the Forest Plan, National Forest Management Act, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), 2014 Farm Bill—Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA), and the Administrative Procedures Act.

Notice of Intent:

Forest Management | Region 1

00003_NOI_Alliance for the Wild Rockies_Willow Creek Veg_Region 1

NOI (dated August 26, 2019) by Alliance of the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystem Council (AWR and NEC) alleging the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Forest Service violated the Endangered Species Act (ESA) pertaining to the Willow Creek Vegetation Management Project (project) on the Helena – Lewis and Clark National Forest (HLCNF) Region 1— The project was approved through use of the 2014 Farm Bill Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) Categorical Exclusion (CE), and concerns the HLCNF Forest Plan’s Amendment 19 road closure requirements.

This NOI is the Second NOI notice filed by AWR and NEC under the ESA. The initial filing was dated June 14, 2019 and concerned Wolverine ESA claims.

BLOGGER’S NOTE: The reference to the HLCNF Forest Plan’s Amendment 19 is incorrect. This is actually a challenge to the 2018 Amendment of the forest plan for grizzly bears that occurred in conjunction with the Flathead Forest Plan revision.

Forest Management | Region 1

00002_NOI_Alliance for the Wild Rockies_North Bridger Project_Region 1

NOI, dated August 30, 2019, by Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council (AWR and NEC) alleging the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Forest service violated the Endangered Species Act (ESA), concerning the North Bridger Project on the Custer Gallatin National Forest, as it pertains to the Canada lynx and its critical habitat (Region 1).

This NOI is the Second NOI notice filed by AWR and NEC under the ESA. The initial filing was dated June 5, 2019 and concerned Wolverine ESA claims.

Natural Resource Management Decisions Involving Other Agencies: Nothing to report

BLOGGER’S NOTE

AWR v. Higgins

The complaint raises NEPA claims regarding the designation of “wildland urban interface” and the development of a community wildfire protection plan. Specifically, the designation of WUI allows the Forest Service to use the HFRA categorical exclusion. The complaint argues that this constitutes Forest Service “adoption” of the community plan and that it did not adequately consider the effects of doing so under NEPA. In fact, the adoption of a plan that determines how national forest lands would be managed must follow the forest planning process in accordance with NFMA. It has always seemed to me that WUI designation changes how national forest lands are managed, and any reference to WUI in a forest plan would require public participation in how that area was identified, and plans for national forest lands can not be viewed as directing national forest management independent of their inclusion in a forest plan. Maybe these issues will come up here.

BLOGGER’S BONUS

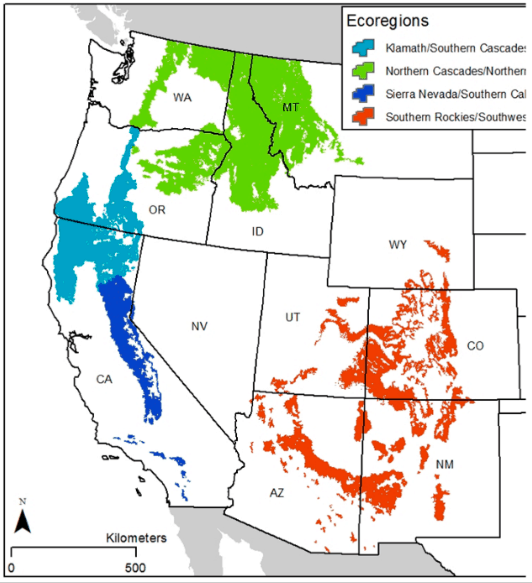

Siskiyou Mountain Salamander

The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that listing of this species, was not warranted despite the loss of BLM regulatory mechanisms discussed previously here. It’s interesting that the FWS stated (as quoted here), “The Yreka Fish and Wildlife Office is working with the Klamath National Forest to develop a conservation strategy for the Siskiyou Mountains salamander, and in Oregon the Roseburg FWO is currently working with the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest and the Medford District Bureau of Land Management to implement a conservation agreement and strategy for this salamander. Together, these actions will help conserve the Siskiyou Mountains salamander on all federal lands across the range of the species.” The ESA caselaw is clear that strategies that do not yet exist can’t be considered “existing regulatory mechanisms” for the purpose of listing decisions, and it’s also been clear that “existing” for national forest lands means included as forest plan components.