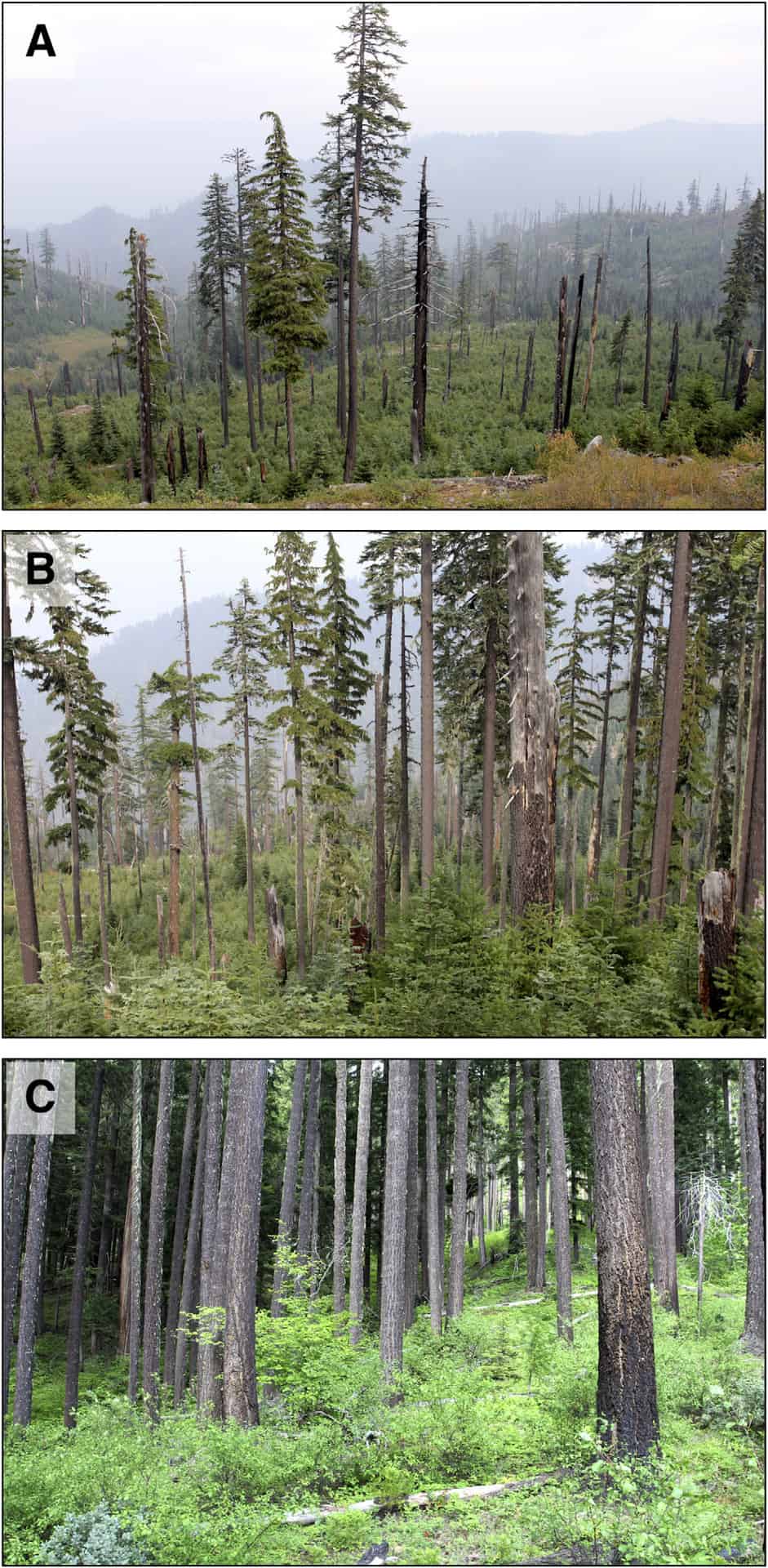

I thought this paper was interesting because the authors directly measured trees, and took photos of the studied stands, which really gives a reader a feel for the study. Here’s a link to the paper itself, and here as described in ScienceDirect.

Highlights

- •Large trees and shade intolerant trees had a higher probability of surviving fire.

- •Radial growth in small trees in burned stands increased.

- •Radial growth in large trees remained suppressed for decades after fire.

- •Radial growth responses can be explained by changes in leaf area.

- •Smaller trees easily add leaf area following fire while larger trees often do not.

These all make sense, in my experience. We used to have the concept of “release” in silviculture. The idea is that if you remove competing trees, sometimes the released tree will grow and thrive, and sometimes it will just sit there or “not release.” It sounds like the large trees may have been old, and some old trees don’t release. Trees don’t release for a variety of reasons, depending on species, age and other factors which silviculturists and silviculture researchers have spent a great deal of time thinking about. Maybe someone can weigh in who knows the studied area, species, etc.?

I think one of points that the authors are making is that one fire severity index measurement can’t really explain what you need to know about trees. If you want to know about stands of trees post-fire, you should measure stands of trees post-fire.

The results we present suggest that fire severity alters forest stand structure not only through mortality but also via individual tree physiological responses. Slower growth in residual trees that results from fire damage may render these trees more vulnerable to mortality in the face of additional stressors (Cailleret et al., 2016; van Mantgem et al., 2003).

We believe it is most likely that fire has a more pronounced longterm effect on radial growth of tall-statured and large diameter trees than smaller trees because recovery of a tree’s leaf area following disturbance is achieved primarily through height growth and the addition of new branches. Large trees at or near their maximum height potential have limited capacity to recover in this fashion, instead relying on the creation of epicormic branches and more complex crown structures to add leaf area without exceeding the tensile strength of the water columns (Van Pelt and Sillett, 2008; Ishii and Ford, 2001; Waring et al.,1982). This has important implications for wildlife species reliant on complex crown or branch structure for nesting, such as northern spotted owl or marbled murrelet (Bond et al., 2009; Ritchie, 1988; Franklin et al., 1981). Fire disturbance may be an important mechanism for creating these features and the persistence of these species in the Pacific Northwest (Fig. 9)

Although we show that MTBS severity classifications are associated with distinctive tree-scale effects, the differential response to fire of trees of different sizes and species suggests that it is important to contextualize field measured or satellite-derived severity metrics by forest structural and compositional attributes. The same fire severity as measured by standard indexes may have different implications for

future forest dynamics depending on residual tree structure and composition. Fire intensity and individual tree resistance drive residual tree structure and composition following fire. As we continue to develop heuristics and management strategies based on fire severity maps, it becomes increasingly important that we find ways to quantify pre-fire forest structure to better understand the future trajectory of forests following disturbance.