For those who have been missing this (click links for more) …

Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Update: The energy companies wanting to build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline across the George Washington and Monongahela National Forests are appealing a reversal of that decision to the U. S. Supreme Court. The 4th Circuit Court of appeals held that the Forest Service improperly amended their forest plans to allow it (discussed here).

Rock Creek Mine (no link)

New lawsuit: Ksanka Kupaqa XaʾⱠȼin v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In the latest case in long-running litigation against the Rock Creek copper and silver mine on the Kootenai National Forest, Plaintiffs challenge failure to reinitiate ESA consultation regarding the mine’s impacts on grizzly bears. Plaintiffs also challenge the legality of FWS’s 2017 bull trout biological opinion and the Forest Service’s authorization for the first phase of the project in reliance on the challenged FWS decisions.

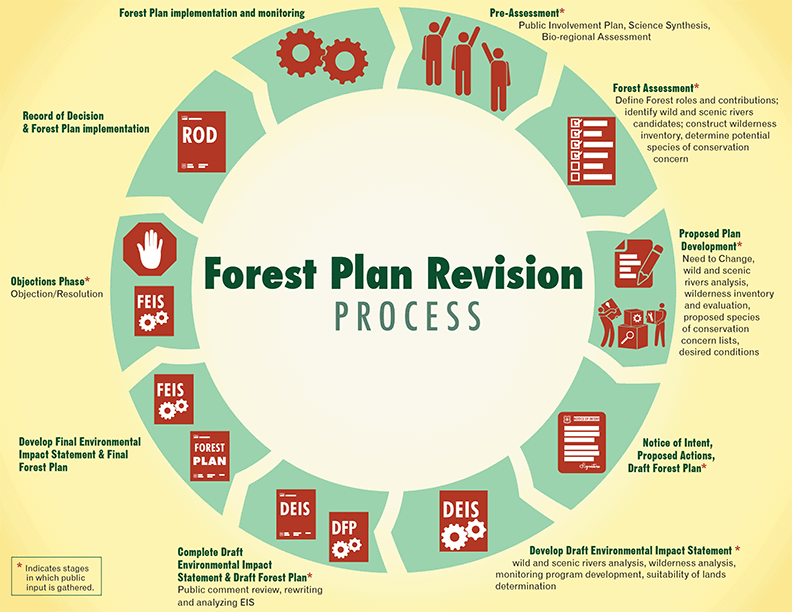

Beaverhead-Deerlodge forest plan

Update: The Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest has decided not to issue any new decisions on timber or vegetation projects until it has completed consultation on the effects of its 2009 revised forest plan on Canada lynx, a species that was found on the forest after previous consultation on the revised plan occurred. This is the result of the NEC v. Krueger lawsuit on the Fleecer Mountains Project discussed here and here.

Flathead Glacier Loon project

Update: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has enjoined the Glacier Loon Project on the Flathead National Forest pending resolution of an appeal from a district court that upheld the Project. Plaintiffs say the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service didn’t properly analyze the project’s potential harm to threatened grizzly bears and Canada lynx and wolverines that are proposed for listing, including cumulative effects of the adjacent Beaver Creek project (also being litigated).

Elkhorn Mountains BLM

New decision: The Montana Federal District Court has enjoined a logging and prescribed burning project on BLM land in the Elkhorn Mountains, which are jointly managed with the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. A supplemental environmental analysis is being required to consider cumulative effects.

Elkhorn Mountains Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest

Also in the Elkhorn Mountains (and who knows, maybe a future lawsuit), the Strawberry Butte Front Country Trail Management Project calls for adding 39 miles of hiking and biking trails to the U.S. Forest Service trail system within a uniquely designated wildlife management unit. The system would designate 28 miles of trail that currently exists but is not recognized by the Forest Service, as well as 11 miles of new trail construction. One complaint during the public comment period: “inviting bike enthusiast from all over the country to the north Elkhorns.”

Kaibab travel plan

New decision: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has upheld a travel plan decision and environmental analysis by the Kaibab National Forest to allow hunters to drive up to a mile off certain routes to pick up big game. According to the State of Arizona the decision was needed to help cull oversized herds of bison that roam areas of the forest near Grand Canyon National Park. Plaintiffs cited potential danger to the habitat of Mexican spotted owls and the black-footed ferret, both endangered species.

Visitor fees

New decision: The Colorado U.S. District Court upheld the Aspen-Sopris Ranger District’s right to charge $10 per vehicle to visit the Maroon Bells Scenic Area. The judge ruled that it didn’t matter if a person doesn’t use the services offered. The plaintiff’s attorney filed a notice of appeal in the 10th Circuit Court; the Recreation Enhancement Act forbids the Forest Service from charging a fee “solely for parking” or for general access to public lands, she said in an email.

Wolf Creek Ski Area inholding

Update: Rio Grande National Forest Supervisor Dan Dallas on Wednesday announced a new decision to provide reasonable access to a 288-acre private property parcel adjacent to Wolf Creek Ski Area. The property owner plans to construct a year-round resort known as the Village at Wolf Creek. Previous litigation was discussed here. Coincidentally, a U.S. magistrate judge has ordered the Forest Service to release documents asked for in the FOIA request that sought information about political intervention in the Wolf Creek decision. The law required the release of the documents by last August.

Nestle bottled water

Update: In another FOIA case, the Forest Service was able to withhold records pertaining to Nestle’s special use permit and water diversion and transmission facilities at Strawberry Creek in the San Bernardino National Forest pursuant to the “trade secrets” exemption.

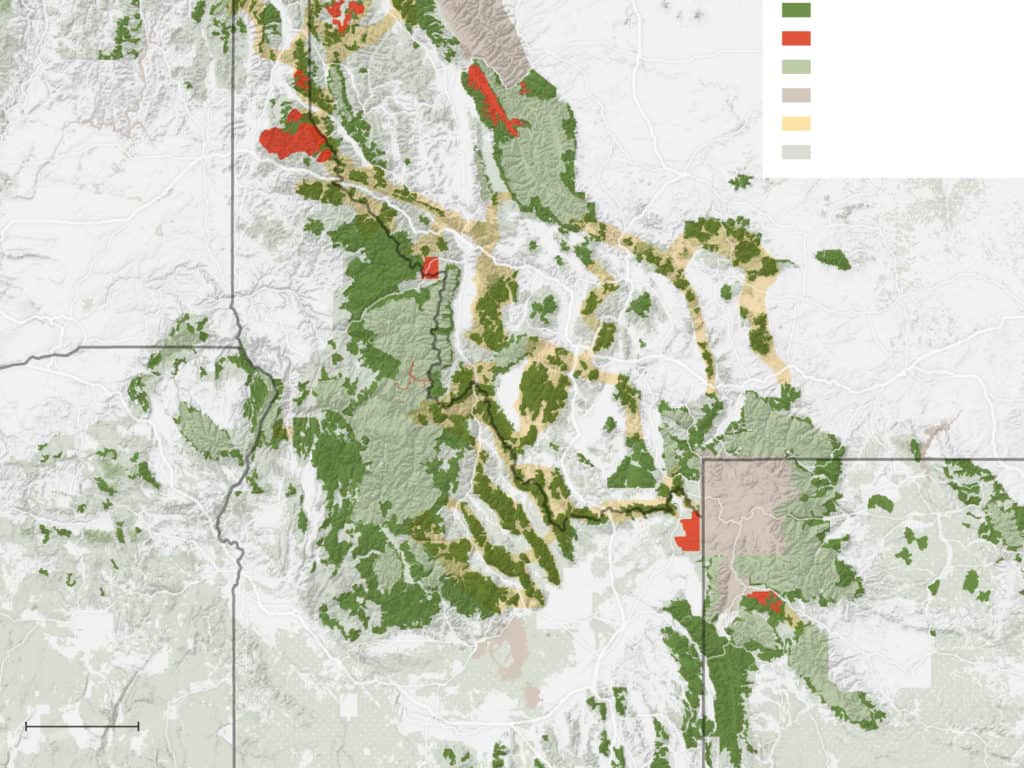

Bi-state sage-grouse

Update: Four environmental groups have intervened on the side of the Forest Service to defend its decision in the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest Plan to protect the listed population of bi-state sage-grouse from motorized users. “The Forest Service did the right thing by strengthening sage-grouse protections under the Humboldt-Toiyabe plan,” said Taylor Jones, endangered species advocate for WildEarth Guardians.

Greater sage-grouse

Future litigation: As for the greater sage-grouse, which was not listed under ESA because the Forest Service and BLM amended their land use plans to include a species conservation strategy, the BLM has changed their plans again to remove key protective measures that would have avoided development in the areas most important to sage-grouse. The Forest Service is likely to follow (although their website is still touting the benefits of their existing conservation measures).

Humboldt-Toiyabe oil and gas leases

No action alternative selected: Also on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, the Forest Service probably avoided another lawsuit by deciding to not allow oil and gas leases on almost 53,000 acres of the Ruby Mountains in Nevada. The Forest Supervisor said his decision was based on overwhelming opposition to the idea and “unfavorable geologic conditions” that suggest there is little to no oil and gas potential in the area. On that latter point, maybe he could have figured it out a little earlier and avoided a little work? And now they have to allow an objection?

Blue Mountains forest plan revisions

No action alternative selected: The Forest Service has decided to not revise the forest plans for the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon and Washington, apparently in response to local complaints that they could not accept any of the action alternatives because of the social and economic impacts. (This was prophesied here.) “For now, the forests will be managed under a previous plan, with a few minor changes.” There is no mention of an objection process for this decision (including the “minor changes”).

Monongahela hydroelectric project

No action proposed: Unlike their decision on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, the Monongahela National Forest successfully used its forest plan to block a proposal to build a water-powered electrical facility. The Forest Supervisor wrote that the project would adversely affect parts of the Forest, including species and vegetation. “In addition to denying the SUP proposal because the proposed licensing studies are inconsistent with the Forest Plan, the project itself would be antithetical to the Forest Plan,” he wrote. This rejection is not subject to administrative appeal. As with the Pipeline, the politicians are now being asked to help.

Forest Service prosecutions:

Helena-Lewis and Clark mining

Umatilla mining

Sequoia marijuana grow

Tahoe archaeological sites