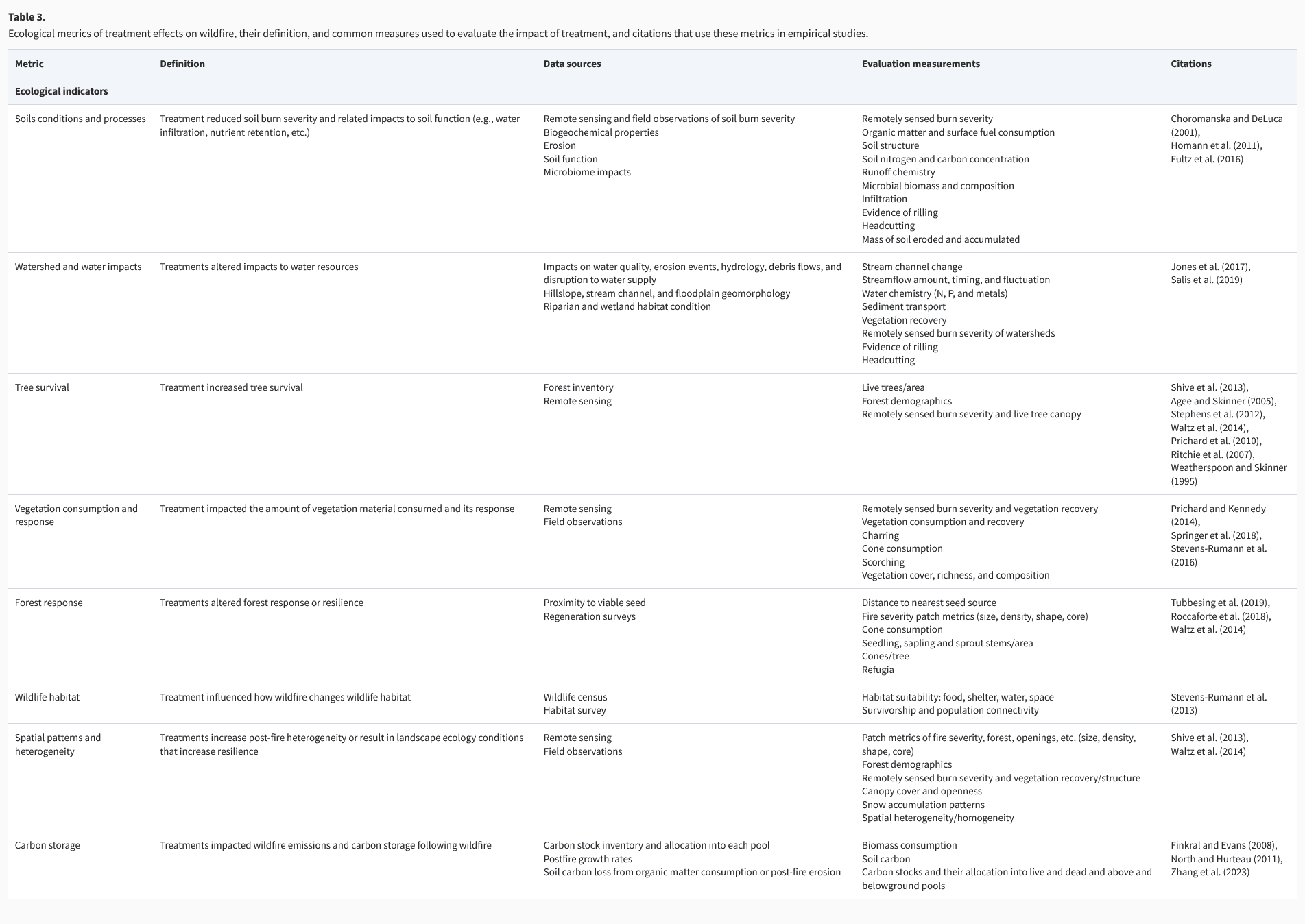

There are three tables of these metrics in the paper, the “ecological” (I would tend to think “biophysical” since are soils and watershed subsets of ecology? Interesting how terminology and associated thinking changes over time) table is posted at the end.

There are three tables of these metrics in the paper, the “ecological” (I would tend to think “biophysical” since are soils and watershed subsets of ecology? Interesting how terminology and associated thinking changes over time) table is posted at the end.

*****************************************

It seems to me that many wildfire/climate studies suffer from a scientific “streetlight effect”. They correlate area burned with weather conditions or other broadscale data and voila! make conclusions. I mentioned this in my comments to Steve’s post last week.

So I’d like to give a vigorous shout-out to the authors of this study. Vorster et al., Journal of Forestry 2023. It’s called “Metrics and Considerations for Evaluating How Forest Treatments Alter Wildfire Behavior and Effects.” Just logically, wouldn’t you want to have a common idea of exactly what “fuel treatment effectiveness” means.. effective in what sense? So these folks decided to dig in and actually talk about 1) different things it could mean, and 2) what data is available to address those things. This seems incredibly obvious and useful, and it’s only surprising to me that no one did it sooner.. otherwise researchers are basically analyzing past each other (like talking past each other only with research studies).

If we were being logical about scientific funding, we’d ask upfront “why are we asking this question? Whom exactly will this knowledge help?” If we identified a group say, land managers or fire suppression folks, we would ask them what information would help them. A serious problem to me is (and it has been in the past, and continues) researchers often define the problem their own way and then make a strange left turn at the end of the proposal and paper claiming that this information will be useful to people. Nowhere in the chain does there appear to be a reality check, or an advocate for the people whose work is claimed to have been helped.

What I really like about this paper is that this group of researchers decided to dive into all these questions and laid out a framework for a common language. It’s great that this effort was funded (by NIFA, CFRI , NSF and the Forest Service).

Interpretations of forest treatment effects in moderating fire impacts, and whether treatments are deemed effective, can vary widely depending on the audience. Treatment effects are objective measures of the influence on wildfire parameters, whereas effectiveness connotes a human judgment of this effect relative to a value-based goal. News media and the public often ascribe a treatment’s effectiveness to a few metrics: did treatments reduce the number of homes or high-value assets lost? Did treatments contain a fire? In contrast, firefighters may be focused on effectiveness through the lens of their ability to defend structures more efficiently or engage in suppression activities that otherwise would not have occurred (Jain et al. 2021). Meanwhile, land managers might be focused on soil impacts and associated short term watershed risks (i.e., debris flows, flooding, sedimentation, threats to drinking water supplies), as well as longer term ecosystem responses to wildfires, such as forest recovery. Interpretations of effectiveness may also change over time, as different outcomes become more or less important to the management goals of a given group.

Treatments can affect wildfires in a number of ways, including changing fire behavior and intensity, fire size, or footprint, altering impacts to ecological processes, facilitating incident operations, reducing suppression costs, and affecting the number of homes and structures lost (Agee and Skinner 2005; Kalies and Kent 2016; Thompson et al. 2013; Weatherspoon and Skinner 1996). However, quantifying the effect of treatments is complicated by the potentially minor influence relative to numerous other factors driving fire behavior, such as vegetation type, fuel arrangement and load, fire weather, topography, time of day of burning, and fire suppression efforts. In studies that look at these factors combined, the dominant influences on fire severity are often temperature, wind, and vegetation cover type (Birch et al. 2015; Evers et al. 2022; Martinson and Omi 2013; Prichard et al. 2020). Another challenge of quantifying the effect of treatments is the integration of data and processes operating at multiple spatial and temporal scales. Further, the scale of intended treatment effects varies widely. For example, some treatments are designed for local effects (e.g., defensible space around a home) whereas others may be designed for landscape effects (e.g., watershed protection). Fire behavior, typically measured as fire intensity, is commonly reduced following prescribed fire and in areas with previous fuels treatments or basal area reductions (Cansler et al. 2022; Kalies and Kent 2016; Prichard et al. 2020; Ritchie et al. 2007; Symons et al. 2008). Given these interacting factors, treatment effects are hard to quantify yet critical to understand as we are faced with growing costs and losses from wildfires (Bayham et al. 2022; Peterson et al. 2021; Steel et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2021) with increasing size and severity of these fires (Abatzoglou and Williams 2016; Stephens et al. 2014).

Evaluating treatment performance relative to stated or implicit objectives and how landscapes should be managed are topics of active research and discussion (Hessburg et al. 2021; Hood et al. 2022; McKinney et al. 2022; Sánchez et al. 2019). We add to these conversations by identifying a range of metrics to measure treatment effects on wildfire outcomes and considerations, challenges, and recommendations when evaluating and communicating about treatment effects. Here, we (1) present a framework to define metrics of treatment effects on wildfires that can be used to evaluate effectiveness of forest treatments for mitigating wildfire behavior and socioeconomic and ecological outcomes and (2) discuss important considerations and recommendations for evaluating these effects of treatments on fires. We draw on experience and literature primarily from the western United States and use the 2020 Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado, USA, as a case study to illustrate these considerations and evaluate the multiple modalities of treatment effects. Quantifying wildfire outcomes in treated areas provides better data-driven rationale for assessing effectiveness, which can aid in setting realistic expectations for how treatments will fare when confronted by extreme fire behavior and thus inform treatment prioritization and justify costs. This framework and these considerations can guide evaluations of treatment effects and assist managers, researchers, policy makers, and the general public in developing a common language for communicating about treatment effectiveness.

I really like this.. this is the opposite of the “streetlight effect”.. these folks actually are asking for the right info to address the question, including firefighter observations. And noting that data collected for different purposes may not be all that helpful for this purpose.

I really like this.. this is the opposite of the “streetlight effect”.. these folks actually are asking for the right info to address the question, including firefighter observations. And noting that data collected for different purposes may not be all that helpful for this purpose.

The treatment effects on wildfire metrics (Tables 1–3) fit into frameworks for characterizing cross-scale cumulative forest treatment impacts, such as the fuel management regime presented by Hood et al. (2022). Conversations about treatment effectiveness are prone to oversimplification and bias by highlighting certain cases to demonstrate a point while ignoring counterfactual evidence. A risk of having so many metrics of effects (Tables 1–3) is that every treatment can be deemed effective or ineffective post hoc by some metric rather than matching postfire metrics with pre-fire intentions for that treatment. We provide the following recommendations for advancing evaluations of treatment effects on wildfire:

Consider multiple treatment effects metrics and consider local context to give a more holistic view of treatment interactions with wildfire and to account for regional differences such as vegetation types, fire regimes, and management practices. Although it is important to align these metrics with the treatment objectives, additional metrics may reveal unintended consequences of treatments and can be just as valuable to adapting treatment methods.

Explore and communicate the range of treatment effect outcomes across burn conditions, treatment characteristics, spatial and temporal scales, and treatment effects metrics.

Improve documentation of suppression activities and firefighter observations, as they are critical for assessing many of the metrics and for attributing the effect of treatment or other drivers of fire behavior.

Improve treatment databases by providing more details and complete attribution of treatment prescriptions, adding historical treatments, providing regular updates, and working towards standardization across agencies so that data can be more readily used during wildfires by incident management teams and firefighters and so effects can be more accurately and efficiently measured.

Advance capabilities to evaluate treatment effects by improving methods for evaluating landscape-scale treatment effects, integrating diverse data streams, and targeting effects that have been difficult to quantify (e.g., watershed impacts, wildlife impacts, fire suppression and postfire recovery costs).

These recommendations can help to better characterize and communicate treatment effects on wildfire, but determining what is effective incorporates additional considerations, such as value systems, management goals, and treatment costs.

Here’s the figure with the ecological indicators..