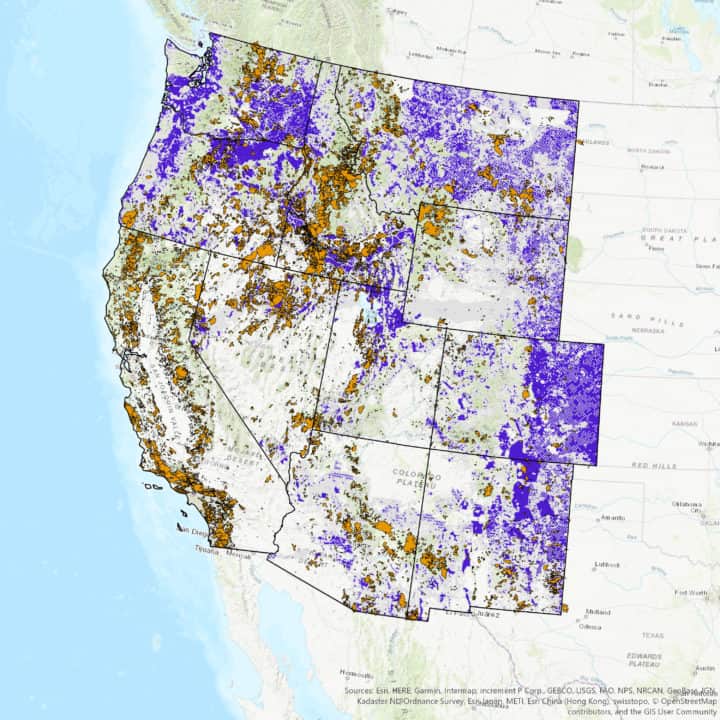

Outdoor Recreation Industry Roundtable (ORIR)

Photo credit: Tami Heilemann

Ruben Navarrette, a syndicated columnist who shows up in the Colorado Springs Gazette op-ed page, recently wrote a column in which he talks about the importance of context in news stories. I like to think of news stories as newborn babies, and the work of NCFP regulars as wrapping the stories in a warm, fluffy blanket of context. Navarette gives some examples and concludes:

Context changes a minor story from what one president is doing wrong into a major story about what’s wrong with our political system.

What he is saying is that our fluffy blankets of context can add not only to fairness and accuracy, but ultimately also to framing problems differently. Here’s an easy example from our own subject area.

This is from Greenwire via the Society for Environmental Journalism here.

“Andrew Wheeler met with a range of companies and trade groups with interests before EPA after he took charge at the agency….

Wheeler was scheduled to call or meet with executives for the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, BP America, Delta Air Lines and Valero Energy Corp. during that month, according to the document. In addition, he was slated to take meetings with agricultural interests, like the American Soybean Association and CropLife America.”

Wheeler met with groups with “interests before EPA”. Oh my goodness. This news story seems to assume that the best regulation is done without speaking to the regulated about their views and concerns. Logically, then Secretaries of the Interior should not meet with members of the Outdoor Recreation Industry? If, on the other hand, we want to add context, as Navarrette suggests, to “what’s wrong with the political system” we can look across administrations, and also in the eyes of state and local government officials.

Here’s a link to quotes from a letter by former Wyoming Governor Dave Freudenthal (D), of Wyoming, to then Secretary of the Interior Salazar about changes in oil and gas regulations.

“I appreciate your stated intentions to restore balance to the leasing program. Unfortunately the proposed changes potentially hand significant control over oil and gas exploration, development and production to the whims of those that profess a ‘nowhere, not ever’ philosophy to surface disturbance of any kind,” Freudenthal wrote Salazar on Jan. 8.

“I have always been a strong proponent of balance” but “Washington…seems to go from pillar to post to placate what is perceived as a key constituency. I only half-heartedly joke with those in industry that, during the prior administration, their names were chiseled above the chairs outside the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Lands and Minerals. With the changes announced [by Interior earlier this month] I fear that we are merely swapping the names above those same chairs [with] environmental interests, giving them a stranglehold on an already cumbersome process,” Freudenthal said.

Freudenthal seems to wonder whether citizens are well-served by disruptive flip flops on policy associated with administrations who change the advisory input from “lots of x” to “never, nohow, no way x” based on listening predominantly to one set of interest groups. The impacted states might prefer a more pragmatic and less ideological middle path, with a focus on reducing impacts rather than removing industry. They were good questions in 2010, IMHO, and remain good questions today.