Previous posts have discussed how where we choose to live contributes to the effects of climate change, both by promoting carbon lifestyles and building in locations at risk. The Missoula Organization of Realtors hosted a conference on the effects of climate change on their industry. This is a step in the right direction. Missing from the presentation though were the perspectives on urban interface living from local government planners and public land managers.

2015: Another Summer of Industry’s Discontent

The following article is written by Keith Hammer, Chair of the Swan View Coalition in Montana. Hammer has shared his views on this blog before – including raising red flags about some types of ‘collaboration’ in Montana. – mk

When there is wildfire smoke in the air, the timber industry and its cronies in Congress blame it on a lack of logging. As though logging prevents wildfires, which it does not. Moreover, they blame the alleged lack of logging on lawsuits brought by conservation groups simply wanting to insure the Forest Service follows the law as it logs public fish and wildlife habitat.

In February, Senator Jon Tester (D-MT), emphatically and falsely told Montana Public Radio “Unfortunately, every logging sale in Montana right now is under litigation. Every one of them.”

Listeners, including Swan View Coalition, challenged Tester’s statement. The Washington Post investigated and found there to be 97 timber sales under contract in Montana’s national forests with only 14 of those being litigated and only 4 of those stopped by a court order! The Post awarded Tester “Four Pinocchios” and noted the Forest Service responded “Things should be litigated that need to be litigated. If there is something the Forest Service has missed, it is very healthy. We absolutely should be tested on that.”

Then politicians and the Forest Service went back to lying as though this never happened. Representative Ryan Zinke (R-MT) visited Essex on the border between Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest and claimed the summer’s wildfire smoke “is completely avoidable.” He went on to promote his Resilient Federal Forests Act, that would speed up federal logging and require citizens to post unaffordable bonds before suing the Forest Service to make it follow environmental laws. He then proposed that future Wilderness designations allow logging to reduce fires.

Such proposals fly in the face of federal studies like the Interior Columbia River Basin Ecosystem Management Project, which found roads and logging render ecosystems less resilient to natural disturbances like fire. Countless other studies find large trees, including fire-killed trees, are essential for fish and wildlife habitat.

Forest Service research shows that forest thinning within the last couple hundred feet of our homes and structures helps save them, not distant logging where fire helps renew natural ecosystems. This summer’s fire that burned the remote and abandoned Bunker Creek bridge shown here was started by lightening in an area burned in 2000.

We’ve supported thinning around the village of Swan Lake, the Spotted Bear Ranger Station, guest ranches, and trail-heads, but such thinning needs to be repeated often to remain effective. Neither the American taxpayer nor our natural ecosystems can afford to apply such front-country logging to the distant backcountry.

As I write this article, Montana’s entire Congressional delegation has done an about-face and is urging the Forest Service to slow down and give loggers more time to log federal timber sale contracts in the face of a glutted timber market.

It’s also time to consider how backcountry logging, most often done at a taxpayer loss, is taking money and market demand away from the thinning that should instead be done adjacent to human homes and other structures.

Timber Industry Fails to Convince Judges that Logging Levels Linked to Wildfires

In a decision dismissing three lawsuits intended to compel more federal land logging in western Oregon, DC federal district court judge Richard Leon found that the timber industry failed to show that less logging means more wildfires (see page 7’s footnote). Judge Leon had ruled earlier in favor of the industry plaintiffs in one of four forum-shopping lawsuits filed by attorney Mark Rutzick. But, judges don’t like being reversed. When the DC circuit court did so in the earlier case, ruling that the timber industry failed to establish standing, Leon took that message to heart and said “ditto” for the other three lawsuits.

Judge Leon’s ruling likely ends a two-decades long legal skirmish by the timber industry to compel federal agencies to increase logging levels from Northwest Forest Plan lands. The campaign has been led by the Portland-based American Forest Resource Council. For 20 years AFRC chose primarily the courts as its strategy to increase logging. Today’s decision suggests that AFRC may change its focus from the courts to Congress, which would play to the strength of its newly-hired executive director, Travis Joseph, former natural resources staff to Oregon Rep. Peter DeFazio. Joseph, who is not an attorney, was DeFazio’s point person during House negotiations over proposed O&C forest legislation that continues to languish in Congress.

Forest Service to pay attorneys fees to industry group that challenged a settlement

The U.S. Forest Service has agreed to pay an oil and gas industry group $530,000 for attorney fees it incurred in a long-running battle over drilling in the Allegheny National Forest, according to a court document filed Thursday.

The Pennsylvania Independent Oil and Gas Association sued to overturn a 2009 agreement between the government and two environmental groups that banned drilling while the agency conducted an environmental impact study. The industry contended that the ban exceeded the Forest Service’s authority.

U.S. District Judge Sean McLaughlin agreed and, in September 2012, permanently overturned the agreement. The 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld his ruling in January 2014.

http://triblive.com/news/allegheny/9152266-74/forest-industry-service#ixzz3n4DOXNQV

I await the cries of indignation.

Forest/BLM planning avoids sage grouse listing; states don’t like that

While the wisdom of Congress prevents the U. S. Fish and Wildlife from saying so, the agency’s draft of the decision to not list the greater sage grouse under ESA states:

“The Federal Plans establish mandatory constraints and were established after notice and comment and review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Therefore, changes to the Federal Plans would require additional notice and comment and further analysis under NEPA. All future management authorizations and actions undertaken within the planning area must conform to the Federal Plans, thereby providing reasonable certainty that the plans will be implemented.”

In 2010, the FWS had found that sage grouse were warranted for listing, in part because of the lack of adequate regulatory mechanisms. The new draft concludes now that, “regulatory mechanisms provided by Federal and three State plans (those with the greatest regulatory certainty) reduce threats on approximately 90 percent of the breeding habitat across the species’ range.” This was a determining factor in reaching the “not warranted” conclusion this time.

Success? Officials in Idaho and Nevada and some mining companies sued the federal government over new restrictions on mining, energy development and grazing that are intended to protect the sage grouse.

Idaho Gov. C.L. “Butch” Otter said Friday that federal officials wrongly ignored local efforts to protect the bird, leading him to sue in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. “We didn’t want a (threatened or endangered) listing, but in many ways these administrative rules are worse,” the Republican governor said in a statement. A similar lawsuit was filed in Nevada by an attorney for two counties and some mining companies.

If these plaintiffs are successful in rescinding the federal plan amendments, the decision to not list the sage grouse would probably no longer be justified (state plans are much more voluntary), and it shouldn’t take the FWS too long to rewrite their conclusion. But I guess that is what the commodity interests want.

Phenotypic Plasticity!

I was on a camping trip last week and one of the stops was at Crater Lake National Park. Within the park are “The Pinnacles”, where I saw this interesting tree, standing out, because of its color. It almost looks like one of those fake tree cell towers. I’m guessing that this is a red fir, on the edge of its elevation range. Of course, we’re all happy about phenotypic plasticity when we look at someone we find attractive.

Also on that trip, I visited Subway Cave, on my old Ranger District at Hat Creek, on the Lassen NF. It is a lava tube where two roof collapses allow you to walk in one way and walk out the other end. A very nice place to stop for lunch.

The Forest Service is Paying Collaborative Partners!

The following article is written by Keith Hammer, Chair of the Swan View Coalition in Montana. Hammer has shared his views on this blog before – including raising red flags about some types of ‘collaboration’ in Montana.

——————

Imagine a world where you donate some time working on a Forest Service project and the Forest Service pays you up to four times what that in-kind donation is worth to continue working on it. This is the world Congress created in the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 as the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP).

The Southwest Crown Collaborative (SWCC) in the Swan-Clearwater-Blackfoot area is one of the collaborative efforts being funded by CFLRP via the Forest Service. Because the Act requires that the collaborative process be “transparent and nonexclusive,” we asked and the SWCC agreed to list on its web site its formal partners, their contributions to projects, and federal contributions to those partners and projects.

In a nutshell, Congress through CFLRP will fund half of the costs of the projects if the Forest Service and its partners fund the other half. Partners need only provide one-fifth of the total project costs, often as in-kind, non-cash donations of work. This minimum one-fifth contribution then entitles the partner to receive federal funds to do work that otherwise would be done by federal employees or under competitive contracts with private businesses.

In a hypothetical example provided by the Forest Service and lodged on the SWCC web site, a partner can consider $2,000 of its work expenses as a non-cash contribution to a project. The Forest Service would pay the partner $5,000 cash, which may include CFLRP funds, “to pay for the partner’s salary, fuel for vehicles, and supplies toward the project.” In a real-life SWCC example, one non-profit has received $2.5 million in federal funds for its non-cash, in-kind contributions of $903 thousand.

While these funds on the one hand enable partners to do some monitoring and watershed restoration work by repairing or decommissioning roads, it also appears to silence public criticisms by partners of the more controversial timber sales being conducted under the guise of “forest restoration.” Moreover, some SWCC partners have collectively promoted “restoration” logging and asked Congress to work with collaborators and not with “organizations and individuals who oppose collaborative approaches to forest management.” (Here)

It is this type of bully behavior by partners that casts a long shadow over the integrity of CFLRP, which at the 5-year/halfway mark is far ahead of its logging quotas and far behind in decommissioning roads and controlling the invasive weeds they bring to the forest. Citizens and scientists that disagree for good reason with the notion that logging is “restoration” (see page 4) deserve equal standing with collaborators being paid millions of tax dollars by the Forest Service.

To see how over $7 million of your tax dollars have thus far been paid to partners in the SWCC, visit:

http://www.swcrown.org/partnership-agreements

Forest planning contributes to listing species under ESA

A recent federal court decision has invalidated the listing of the lesser prairie chicken. A key reason for the court’s decision was that the Fish and Wildlife Service made an assumption that if it didn’t list the species, it would reduce the incentive for participation in a conservation plan. The judge didn’t think that was a valid assumption. The Forest Service seems determined to prove him wrong.

Under the 2012 Planning Rule, the Forest Service has the opportunity to help forestall the need to list species under ESA by identifying them as species of conservation concern and including protective plan components for them. The wolverine received a positive 90-day finding that listing should be considered, but the FWS ultimately decided not to. In response, the three forest plan revision efforts that are proceeding under the 2012 Rule and have wolverine habitat (Nez Perce-Clearwater, Flathead, Helena-Lewis & Clark) have determined that the wolverine should not be identified as a species of conservation concern.

The FWS will be looking for evidence their assumption was correct. The lesser prairie chicken may have the Forest Service to thank when it eventually gets listed. (And the wolverine, too.)

A closer look at Montana’s ‘second-biggest wildfire season so far this decade’

This AP article, which ran in most all Montana newspapers, caught my eye yesterday. I’d like to use it to point out a few things related to wildfires.

The title of the article is “State’s wildfire season second-biggest so far this decade.”

For starters, what’s sort of bizarre, is that the reporter only looked at a 6 year time frame (since 2010) not a decade.

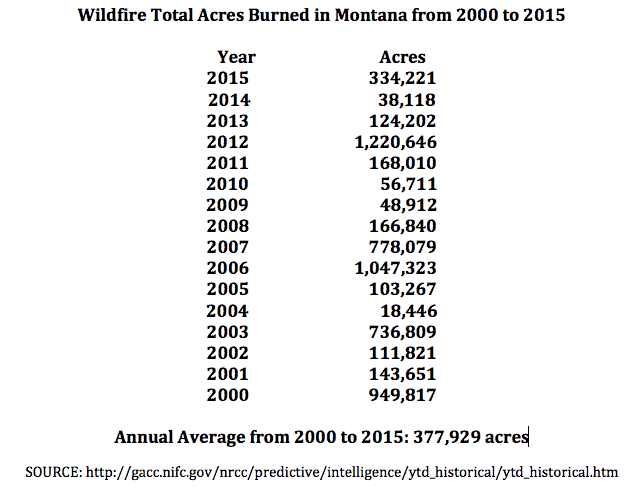

When you dig deeper into the article you see that so far the 2015 wildfire season in Montana (which is quickly coming to a close on account of some weather events last week, as well as more snow and rain coming this week) has only burned 27% of the total acres burned in the 2012 wildfire season in Montana (334,221 acres in 2015 vs 1,220,646 acres in 2012).

Wanting to know more I spent about 30 minutes at this link via the Northern Rockies Coordination Center, which ironically was provided to me by the reporter when I asked him some detailed questions. Why the reporter was unable to apparently spend a few minutes checking out these statistics is a mystery.

So, I copied down all the wildfire burned acres totals in Montana from 2015 going all the back to 2000 (see chart above).

What quickly becomes apparent is the wide range of acres burned from year-to-year.

In fact, based on these numbers a more accurate frame for the AP story about the 2015 wildfire season might have been that so far Montana has seen a little less than the average acres burned going back to 2000.

It’s also worth pointing out that another way of looking at this year’s wildfire season in Montana is that, to date, we’ve only burned 27% to 45% of the acres burned in Montana during the wildfire seasons of 2012, 2007, 2006, 2003 and 2000.

While technically the title of the article, and framing of the story is correct, I’d put forth that there are much more accurate (although, perhaps less ‘flashy’ and ‘sensationalistic’) ways of looking at Montana’s 2015 wildfire season.

Looking at the chart going back to 2000 another issue that becomes apparent, to me anyways, is that there appears to be no correlation whatsoever between the total burned acres and the amount of national forest logging and/or national forest lawsuits; although that fact certainly doesn’t stop some from within the logging industry or politicians from trying to always make that case.

Of course, it goes without saying that weather conditions such as drought, heat and wind have a huge impact on the total number of acres burned, as do long-term climate factors. Another issue is total number of ignitions (whether by people or dry lightening storms) and what part of the state the ignitions occur in (i.e. eastern grasslands vs western forests).

I’ve lived in Montana since 1996 and have to say that compared with my home state of Wisconsin it always seems very dry out here, whether or not we are technically in the grips of drought, which we certainly are in now.

So perhaps ignitions are even more of a key factor in the total number of acres burned in Montana in any given year, rather than drought.

I also suspect that wind plays a huge role in all of this. Really, the common denominator in all major wildfires is wind. No wonder some people find wind so annoying.

This information is not meant to discount specific experiences communities, homeowners or citizens have had with wildfires this year, but just serves as a bit of important, fact-based information and context, at least as far as Montana’s wildfire season goes.

As I’ve said before, information like this is especially important in the context of recent statements (and pending federal legislation) from certain politicians blaming wildfires on a lack of national forest logging or a handful of timber sale lawsuits.

If politicians are going to predictably use another wildfire season to yet again weaken our nation’s key environmental or public lands laws by increasing logging (including calls by politicians like Montana’s Rep Ryan Zinke for logging within Wilderness Areas) then the public should at least have some facts and statistics available to help put the wildfires in context.

Despite Rhetoric, Study Finds Severe Wildfires NOT Increasing in Western Dry Forests

A new study from Dr. William Baker of the University of Wyoming titled “Are high-severity fires burning at much higher rates recently than historically in dry-forest landscapes of the western USA?“, was published today in the international scientific journal PLOS ONE, and is freely available here.

Below is a portion of the press release:

LARAMIE, Wyo., Sept. 9, 2015 /PRNewswire/ — Severe wildfires are often thought to be increasing, but new research published today in the international science journal PLOS ONE shows that severe fires from 1984-2012 burned at rates that were less frequent than historical rates in dry forests (low-elevation pine and dry mixed-conifer forests) of the western USA overall, and fire severity did not increase during this period.

The study by Dr. William Baker of the University of Wyoming compared records of recent severe fires across 63 million acres of dry forests, about 20% of total conifer forest area in the western USA, with data on severe fires before A.D. 1900 from multiple sources.

“Infrequent severe fires are major ecosystem renewal events that maintain biological diversity, provide essential habitat for wildlife, and diversify forest landscapes so they are more resilient to future disturbances,” said Dr. Baker. “Recent severe fires have not increased because of mis-management of dry forests or unusual fuel buildup, since these fires overall are occurring at lower rates than they did before 1900. These data suggest that federal forest restoration and wildfire programs can be redirected to restore and manage severe fires at historical rates, rather than suppress them.”

Key findings from the new study:

• Rates of severe fires in dry forests from 1984-2012 were within the pre-1900 range, or were less frequent, overall across the western USA and in 42 of 43 smaller analysis regions.

• It would take more than 875 years, at 1984-2012 rates, for severe fires to burn across all dry forests, which is longer than the range of 217-849 years across pre-1900 forests. These forests have ample time to regenerate after severe fires and reach old age before the next severe fire.

• Severe fires are not becoming more frequent in most areas, as a significant upward trend in area burned severely was found in only 3 of 23 dry pine analysis regions and 1 of 20 dry mixed-conifer regions in parts of the Southwest and Rocky Mountains from 1984-2012. Also, the fraction of total fire area that burned severely did not increase overall or in any region.

• Although not yet occurring in most areas, increases in severe fire projected by 2046-2065 could be absorbed in most regions without exceeding pre-1900 rates, but it would be wise to redirect housing and infrastructure into safer settings and reduce fuels near them.

Pre-1900 rates of severe fires were calculated from land-survey records across 4 million acres of dry forests in Arizona, California, Colorado, and Oregon, and analysis of government Forest Inventory and Analysis records and early aerial photography. These reconstructions are corroborated by paleo-charcoal records at seven sites in Arizona, Idaho, New Mexico, and Oregon.

Dr. William L. Baker is an Emeritus Professor in the Program in Ecology/Department of Geography at the University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming. He is the author of over 120 peer-reviewed scientific publications, and also contributed to the new book, The Ecological Importance of Mixed-Severity Fires: Nature’s Phoenix, which features the work of 27 scientists from around the world.