Some of us will get sucked in to writing answers to these questions.. there sure are a lot! The questions are pretty much about how can the FS plan and use adaptive management in managing for “climate resilience.” Conceivably managing for climate resilience will also help with resilience non-climate biological, physical, economic and social stressors, unless folks have defined those not to exist (Everything Stressful is Due to Climate). It would be handy IMHO if the results of this and a 10- year review of implementation would lead to an amended Planning Rule. A girl can dream… Anyway, below are the questions. I’m still looking for helpful reviews of “why adaptive management hasn’t worked in the past, or has it?” if anyone knows of any.. the above paper is about the approach taken in the NW Forest Plan in 2003.

*********************************************

We are interested in public feedback and requests for Tribal consultation on a range of potential options to adapt current policies or develop new policies and actions to better anticipate, identify, and respond to rapidly changing conditions associated with climate-amplified impacts. Overarching questions include:

- How should the Forest Service adapt current policies and develop new policies and actions to conserve and manage the national forests and grasslands for climate resilience, so that the Agency can provide for ecological integrity and support social and economic sustainability over time?

• How should the Forest Service assess, plan for and prioritize conservation and climate resilience at different organizational levels of planning and management of the National Forest System ( e.g., national strategic direction and planning; regional and unit planning, projects and activities)?

- What kinds of conservation, management or adaptation practices may be effective at fostering climate resilience on forests and grasslands at different geographic scales?

- How should Forest Service management, partnerships, and investments consider cross-jurisdictional impacts of stressors to forest and grassland resilience at a landscape scale, including activities in the WUI?

- What are key outcome-based performance measures and indicators that would help the Agency track changing conditions, test assumptions, evaluate effectiveness, and inform continued adaptive management?

Examples, comments, and Tribal consultation would be especially helpful on the following topics:

1. Relying on Best Available Science, including Indigenous Knowledge (IK), to Inform Agency Decision Making.

a. How can the Forest Service braid together IK and western science to improve and strengthen our management practices and policies to promote climate resilience? What changes to Agency policy are needed to improve our ability to integrate IK for climate resilience—for example, how might we update current direction on best available scientific information to integrate IK, including in the Forest Service Handbook (FSH) Section 1909.12?

b. How can Forest Service land managers better operationalize adaptive management given rapid current and projected rates of change, and potential uncertainty for portions of the National Forest System?

c. Specifically for the Forest Service Climate Risk Viewer (described above), what other data layers might be useful, and how should the Forest Service use this tool to inform policy?

2. Adaptation Planning and Practices. How might explicit, intentional adaptation planning and practices for climate resilience on the National Forest System be exemplified, understanding the need for differences in approach at different organizational levels, at different ecological scales, and in different ecosystems?

a. Adaptation Planning:

i. How should the Forest Service implement the 2012 Planning Rule under a rapidly changing climate, including for assessments, development of plan components, and related monitoring?

1. How might the Forest Service use management and geographic areas for watershed conservation, at-risk species conservation and wildlife connectivity, carbon stewardship, and mature and old-growth forest conservation?

ii. How might the Forest Service think about complementing unit-level plans with planning at other scales, such as watershed, landscape, regional, ecoregional, or national scales?

a. Adaptation Practices:

i. How might the Agency maintain or foster climate resilience for a suite of key ecosystem values including water and watersheds, biodiversity and species at risk, forest carbon uptake and storage, and mature and old-growth forests, in addition to overall ecological integrity? What are effective adaptation practices to protect those values? How should trade-offs be evaluated, when necessary?

ii. How can the Forest Service mitigate risks to and support investments in resilience for multiple uses and ecosystem services? For example, how should the Forest Service think about the resilience of recreation infrastructure and access; source drinking water areas; and critical infrastructure in an era of climate change and other stressors?

iii. How should the Forest Service address the significant and growing need for post-disaster response, recovery, reforestation and restoration, including to mitigate cascading disasters (for example, post-fire flooding, landslides, and reburns)?

iv. How might Forest Service land managers build on work with partners to implement adaptation practices on National Forest System lands and in the WUI that can support climate resilience across jurisdictional boundaries, including opportunities to build on and expand Tribal co-stewardship?

v. Eastern forests have not been subject to the dramatic wildfire events and severe droughts occurring in the west, but eastern forests are also experiencing extreme weather events and chronic stress, including from insects and disease, while continuing to rebound from historic management and land use changes. Are there changes or additions to policy and management specific to conservation and climate resilience for forests in the east that the Forest Service should consider?

3. Mature and Old Growth Forests. The inventory required by E.O. 14072 demonstrated that the Forest Service manages an extensive, ecologically diverse mature and old-growth forest estate. Older forests often exhibit structures and functions that contribute ecosystem resilience to climate change. Along with unique ecological values, these older forests reflect diverse Tribal, spiritual, cultural, and social values, many of which also translate into local economic benefits.

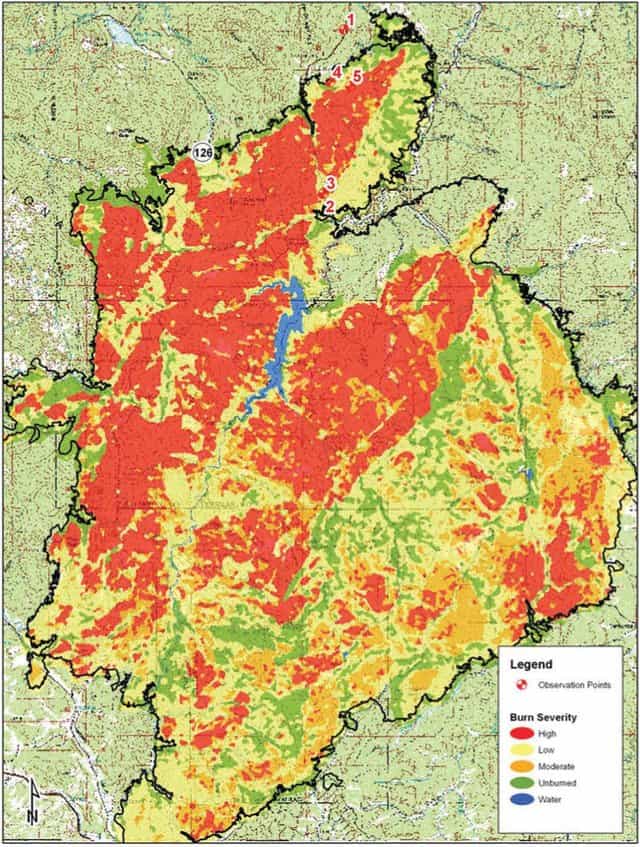

Per direction in E.O. 14072, this section builds on the RFI to seek public input on policy options to help the Forest Service manage for future resilience of old and mature forest characteristics. Today there are concerns about the durability, distribution, and redundancy of these systems, given changing climate, as well as past and current management practices, including ecologically inappropriate vegetation management and fire suppression practices. Recent science shows severe and increasing rates of ecosystem degradation and tree mortality from climate-amplified stressors. Older tree mortality due to wildfire, insects and disease is occurring in all management categories.

The Forest Service is analyzing threats to mature and old-growth forests to support policy development to reduce those threats and foster climate resilience. Today’s challenge for the Forest Service is how to maintain and grow older forest conditions while improving and expanding their distribution and protecting them from the increasing threats posed by climate change and other stressors, in the context of its multiple-use mandate.

a. How might the Forest Service use the mature and old-growth forest inventory (directed by E.O. 14072) together with analyzing threats and risks to determine and prioritize when, where, and how different types of management will best enable retention and expansion of mature and old-growth forests over time?

b. Given our current understanding of the threats to the amount and distribution of mature and old-growth forest conditions, what policy, management, or practices would enhance ecosystem resilience and distribution of these conditions under a changing climate?

4. Fostering Social and Economic Climate Resilience.

a. How might the Forest Service better identify and consider how the effects of climate change on National Forest System lands impact Tribes, communities, and rural economies?

b. How can the Forest Service better support adaptive capacity for underserved communities and ensure equitable investments in climate resilience, consistent with the Forest Service’s Climate Adaptation Plan, Equity Action Plan and Tribal Action Plan?

c. How might the Forest Service better connect or leverage the contribution of State, Private and Tribal programs to conservation and climate resilience across multiple jurisdictions, including in urban areas and with Tribes, state, local and private landowners?

d. How might the Forest Service improve coordination with Tribes, communities, and other agencies to support complementary efforts across jurisdictional boundaries?

e. How might the Forest Service better support diversified forest economies to help make forest dependent communities more resilient to changing economic and ecological conditions?