This was circulating around at work today…

From E&E News here..

This is enough to give you a flavor.

ARLINGTON, Va. — Peter Kareiva had come to answer for his truths.

Settling at the head of a long table ringed by young researchers new to the policy world, Kareiva, chief scientist of the Nature Conservancy, the world’s largest environmental organization, cracked open a beer. After a long day mentoring at the group’s headquarters, an eight-story box nestled in the Washington, D.C., suburbs, he was ready for some sparring.

The scientists had read Kareiva’s recent essay, which takes environmentalists to task. The data couldn’t bear out their piety, he wrote. Nature is often resilient, not fragile. There is no wilderness unspoiled by man. Thoreau was a townie. Conservation, by many measures, is failing. If it is to survive, it has to change.

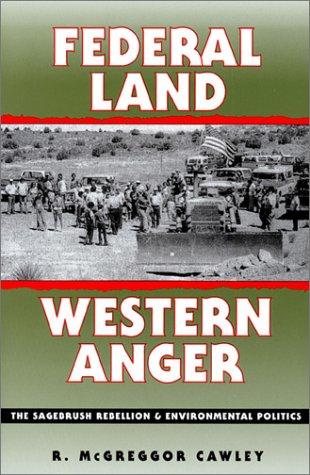

image removed

Inducted last year into the National Academy of Sciences, Kareiva continues to teach part-time at Santa Clara University. Photo by Dave Lauridsen. Courtesy of the Nature Conservancy (TNC).

Many around the table were unconvinced. Some were disturbed.

How could this be coming from the Nature Conservancy?

“We love the horror story,” Kareiva said. He was dressed in New Balance running shoes, a purple sweater and rumpled tan trousers. “We just love it. The environmental movement has loved it. That, I think, is … [a] strategy failure. And it’s actually not supported by science.”

This is not some vague hypothesis, he added to murmurs. He’s seen it in the data.

“The message [has been that] humans degrade and destroy and really crucify the natural environment, and woe is me,” he said. “The reality is humans degrade and destroy and crucify the natural environment — and 80 percent of the time it recovers pretty well, and 20 percent of the time it doesn’t.”

One of the visitors, Lisa Hayward, an ecologist working on invasive-species policy at the U.S. Geological Survey, spoke up. How can that be so? “I feel that does not represent the consensus of the ecological community,” she said.

“I’m certain that it doesn’t represent the consensus of the ecological community,” Kareiva shot back, with a smile and flash in his eyes. A circle of nervous laughter swayed around the room. “I’m absolutely certain of that! Wait two years.”

Kareiva has never feared following the data, or dragging others with him. Already a respected ecologist, for the past decade he has shoved the Nature Conservancy toward a new environmentalism. The old ways aren’t working. Inch by inch, for better or worse, conservation must, he says, enter the Anthropocene Epoch — the Age of Man.

For most of the conservancy’s history, the old way meant one thing: buying and protecting land from human development, through any means necessary. “Saving the Last Great Places on Earth,” the old Nature Conservancy motto went. And it worked. Backed by wealthy donors and corporate deals, the conservancy has long been one of the largest landowners in the United States. Worldwide, it has protected more than 119 million acres.

But not all of its trends point up.

The average age of a conservancy member is 65. The average age of a new member is 62. Each year, those numbers creep upward. Only 5 percent of the group’s 1 million members are younger than 40. Among the “conservation minded” — basically, Americans who have tried recycling — only 8 percent recognize the group. Inspiration doesn’t cut it anymore. Love of nature is receding. The ’60s aren’t coming back.

It’s a problem confronting all large conservation groups, including the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International and the Wildlife Conservation Society. Quietly, these massive funds — nicknamed the BINGOs, for “big nongovernmental organizations” — have utterly revamped their missions, trumpeting conservation for the good it does people, rather than the other way around. “Biodiversity” is out; “clean air” is in.

“In fact, if anything, this is becoming the new orthodoxy,” said Steve McCormick, the Nature Conservancy’s former president. “It’s widespread. Conservation International changed its mission, and it’s one that Peter Kareiva could have crafted.”

For these groups, it’s a matter of survival. But for ecologists like Kareiva, it’s science.

The conservation ethic that has driven these groups — the protection of pristine wild lands and charismatic species into perpetuity — has unraveled at both ends. American Indians dramatically altered the environment for thousands of years, paleontologists have found; even before then, climate shifts followed the planet’s wobbles. And in the future, no land will be spared man’s touch, thanks to human-induced global warming.

The desire to return to a steady-state baseline, before European settlement or human influence, will never work, these scientists say. Many species won’t be saved; some that are saved will not thrive, lingering in a managed existence like the California condor. There is no return to Eden. Population will rise. Triage is coming.

“Conservation is at a crossroads,” said John Wiens, who served with Kareiva as a lead scientist at the conservancy for several years before joining the nonprofit PRBO Conservation Science. “That’s where we are. And we’re likely to be there for some time.”

Kareiva was not the first to see the crossroads. But unlike those of many writers and scientists, his message has come from the inside. And there is every reason to suspect the movement will push back, said Stewart Brand, the environmentalist best known as the editor of Whole Earth Catalog.

“To be the first going somewhat public with this kind of critique from [inside] an organization framework, it’s not only pioneering and important, but brave,” Brand said. “He’s a guy who’s risking his job.”

Here are the last paragraphs:

Ecosystem services are no panacea, though, said Wiens, the former conservancy scientist. It’s a recipe that can easily miss the nonmonetary values of the environment. And it won’t necessarily help managers make the hard choices on what species to save. How will this triage be decided? There are no tools, no paradigm, that can do that yet.

“We don’t have, right now, the framework to think through those cost-benefit calculations,” Wiens said. “And I think that’s partly because people have been avoiding this notion of triage.”

For now, at conservation and ecology conferences, many young scientists speak exactly like Kareiva, said Marvier, his former postdoc. These are the future conservation managers and agency leaders. A generational dynamic is being played out. Kareiva’s team seems to be winning. Team Biodiversity may soon leave the court.

Back at the conservancy’s headquarters, meeting with the young scientists, Kareiva had finished his beer, an India pale ale from Heavy Seas-branded Loose Cannon. It was a good talk. There would be many more like it. Move conservation into working landscapes like farms, he had said. Value nature’s services. Let go of the ideal. And bring in a base beyond affluent, educated whites. Let Thoreau go.

“Broaden the constituency to those loggers,” he said.

The whole article is interesting and you can sign up for a free trial of Greenwire here.

Here is a link to Kareiva’s paper. I think we may have posted it here before, but not sure.