Nice poster, Sage Grouse Initiative!

Somehow I hadn’t been following sage grouse, but apparently there’s another plan in the works. Pew sent out this notification…

Dear Wilderness Supporter,

Populations of the iconic greater sage-grouse have fallen significantly over the past six decades, with an 80% decline across their range since 1965—and half of that drop occurring since 2002. These disturbing findings, together with the Biden administration’s focus on combating climate change, compelled the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)—the largest federal land manager of sage-grouse habitat—to reexamine its management of the 67 million acres of habitat in California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North and South Dakota, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming.

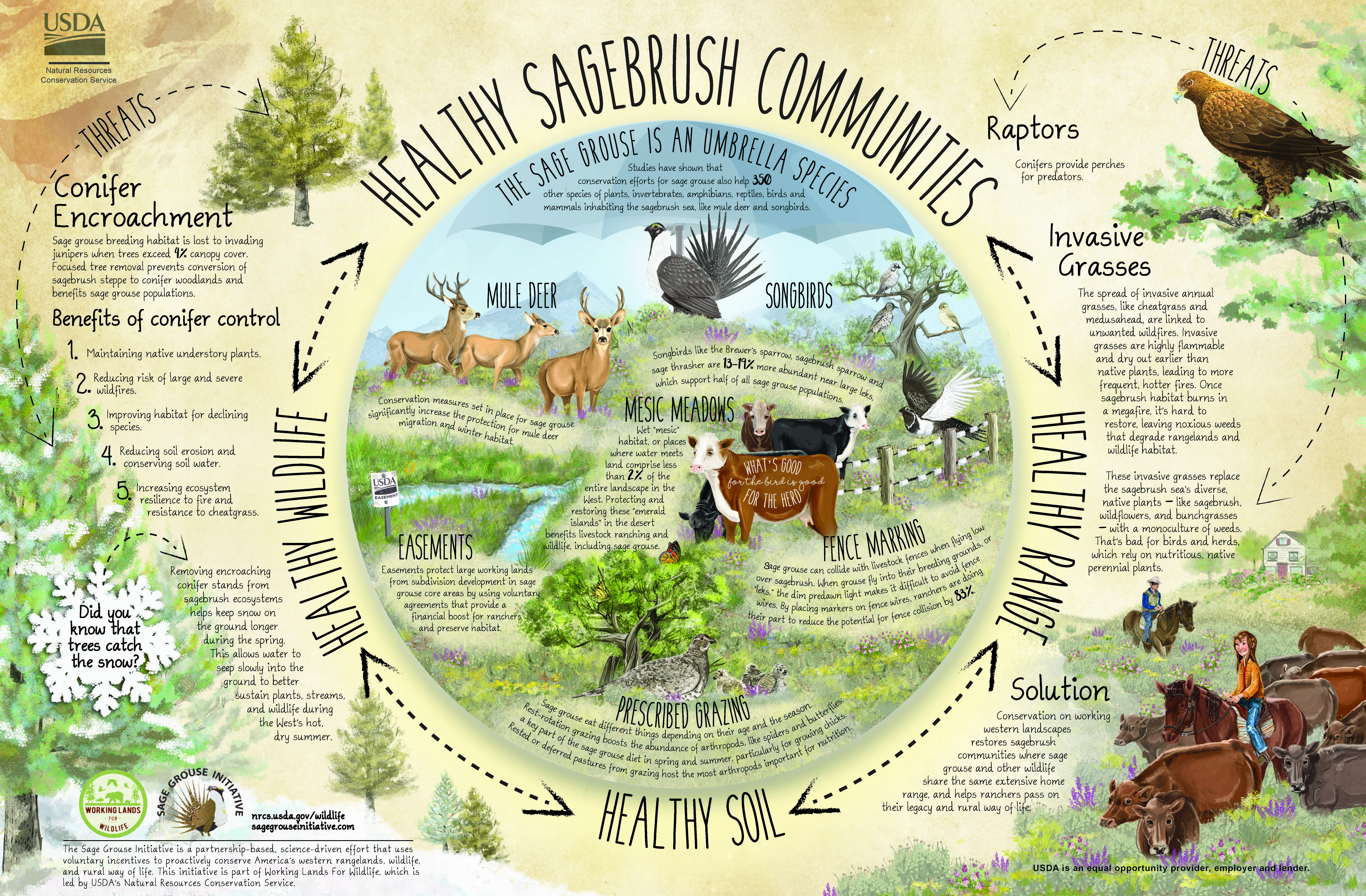

We have an opportunity to slow the alarming decline of the sage-grouse and its habitat. The public comment period closes June 13th! Act now to ensure your voice is heard.The sagebrush steppe of the interior American West covers tens of millions of acres and is one of the nation’s most imperiled ecosystems. Sagebrush landscapes—which are home not only to greater sage-grouse but also to mule deer, pronghorn, pygmy rabbits, and more than 350 other species—continue to shrink rapidly because of a host of growing threats, including wildfire, energy development, and the spread of invasive plant species.

While the draft plan is a step in the right direction, science points to the need for even stronger management so that the greater sage-grouse population can recover. The BLM is requesting public input on its draft plan. Please take a moment to submit your comments so that the BLM hears a resounding message from the public urging it to:

- Provide strong and consistent management action that takes into account changing climatic conditions to stem the ongoing population declines.

- Protect and expand intact landscapes that support sage-grouse and the 350 other species that depend on the sagebrush steppe through designations of Priority Habitat Management Areas and Areas of Critical Environmental Concern.

- Mitigate against any impacts across this vulnerable habitat to ensure the long-term viability of the species.

Please act today to help slow the alarming decline of the sage-grouse and its habitat. The deadline to submit comments is June 13th. Act now!

**************

Note: were it not for the last-minute twist I described in this post. the Obama Admin could have had a sage grouse deal that stuck. Here is what my source said:

Folks from Garfield County, CO did a FOIA and found out that the changes were associated in time with meetings with various environmental organizations, including Pew. One particular idea added during these last changes was the idea of “focal areas”. The States went ballistic.

If the Obama Admin had not listened to these groups, it’s likely that we would have spared the sage grouse workers, BLM folks of all stripes, (and the public) two more goes at this planning effort (one Trump and one Biden).

I’m always interested in lessons learned from various efforts and it turns out that there was a paper written about Wyoming’s lessons learned. Since 2003, Local Sage-Grouse Working Groups worked together (LWGs) , Wyoming also had an SGIT:

In 2007, a statewide SageGrouse Implementation Team (SGIT) was appointed to advise the governor of Wyoming on all matters related to the Wyoming Greater Sage-Grouse Core Area Protection Policy. The Core Area Policy was established by a governors’ executive order and provided mechanisms for limiting human disturbance in the most important sage-grouse habitats. Federal land management agencies have incorporated most aspects of the Core Area Policy into their land use planning decisions

Process and project implementation.

Successes at the statewide scale appeared to be largely the product of sound science used to inform policy making and effective leadership by Governors Freudenthal and Mead as well as the SGIT chairman, Bob Budd. While the potential for ESA listing certainly provided economic motivation for individuals and interests not otherwise dedicated to wildlife and habitat conservation to earnestly participate in the process, charismatic leadership should not be underestimated as a compelling force guiding diverse interests to work cooperatively toward a mutually acceptable outcome. Even so, challenges remain at both the local and state scale. These include:

• Increasingly infrequent LWG meetings impact group dynamics, as LWG members need to refresh their memories and reestablish working relationships.

• LWG project outcomes are often unquantified and undocumented, so their effectiveness is uncertain.

• The consensus decision-making model often results in more discussion and deliberation on an issue than would have occurred under a simple majority vote model. In the Wyoming LWGs, this appears to have led to better decisions being made. However, the resulting decisions can alternatively be a compromise that insufficiently addresses an important issue, but stands nonetheless as parties to the decision prioritize cooperation over outcome.

• Some individual LWG members harbor modest resentment of the SGIT, which has greater policy-making influence. Including more LWG representation on the SGIT could improve these relationships.

• Although adaptive management is an operative concept in the CAP, the reality is that people, and especially business, prefer stability and certainty. Consequently, resistance to change can be a difficult challenge to overcome, even in the face of compelling science.

• Overriding of advisory group recommendations by decision-makers may threaten the success of the group process. Examples of this include the federal designation of “Sagebrush Focal Areas” in the federal land-use planning process completed prior to the 2015 listing decision, the Department of Interior Secretarial Order 3353 directing review of all planning decisions made by the previous administration relative to sage-grouse, and 2016 legislation in Wyoming allowing private bird farms to collect eggs from wild sage-grouse and develop captive flocks. Each of these decisions was made with no or minimal consideration of established advisory group processes, resulting in concern from various participants that might

undermine their interest in continuing to be involved.Paramount to all is the fact that both the local and state processes are reliant on the ability of diverse participants, who often hold adversarial viewpoints, to develop and maintain positive working relationships in seeking to achieve mutually agreeable goals. We believe the Wyoming model has potential to succeed in an era of political polarization.

I think there’s probably a better way to go than Partisan Policy Ping-Pong on western lands. Hopefully the Biden Admin will ultimately pick something of a more peace-keeping and likely to be permanent nature, and not a pre-election sharp stick in the eye that would lead us into another round of (potentially pointlessly provocative) planning..