Court decision in Central Oregon Landwatch v. Connaughton (9th Cir.)

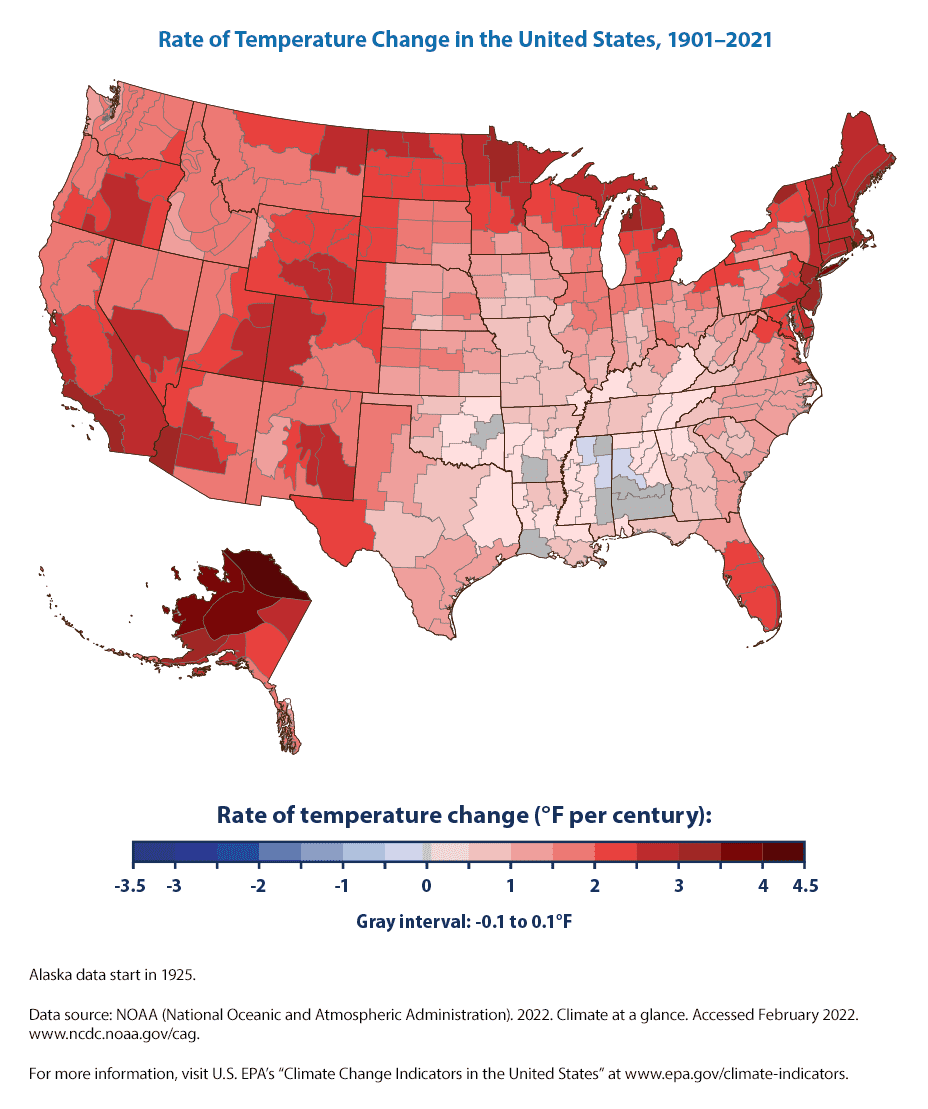

On October 23, the circuit court upheld a special use permit granted by the Deschutes National Forest to the City of Bend to upgrade its Bridge Creek intake facility, construct a new pipeline, and operate the system for 20 years. The court found that the permit was consistent with the forest plan’s Inland Native Fish Strategy guidelines to “avoid effects that would retard or prevent attainment of the [interim water temperature Riparian Management Objectives (RMOs) established by INFISH] and avoid adverse effect on inland native fish.” The court also found that the EA’s failure to evaluate a “no diversion” alternative was not arbitrary or capricious, and that the analysis of climate change did not have to be quantitative because it affected streamflow in both alternatives equally. (The link to the opinion at the end of the article works.)

Court decision in Gescheidt v. National Park Service

On February 27, the district court held that the Park Service has no statutory duty to revise its 1980 General Management Plan for the Tomales Point portion of the Point Reyes Seashore to address the fact that elk are dying from starvation and dehydration as a result of a fence that limits their movement into areas that would compete with livestock.

Court decision in Great Basin Resource Watch v. U. S. Department of the Interior (D. Nev.)

On March 31, the district court vacated the BLM’s approval of Eureka Moly’s planned molybdenum mine about 250 miles east of Reno. The judge cited the 9th Circuit’s ruling in an Arizona case (Rosemont Mine) last year that upended the government’s long-held position that the 1872 Mining Law conveys the same rights established through a valid mining claim to adjacent land for the disposal of tailings and other waste without having to show that valuable minerals are present there. This article provides more background and discusses proposed legislation to reverse these rulings.

New lawsuit: Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center v. U. S. Bureau of Land Management (D. Or.)

On April 10, four environmental groups sued the BLM over its approval of the Programmatic Integrated Vegetation Management for Resilient Lands Program and the Late Mungers Project Determination of NEPA Adequacy. The program was not specific about where logging would occur, but would include late successional reserves established in the Northwest Forest Plan which would allegedly be inconsistent with that plan. The complaint also alleges a violation of NEPA for failure to prepare an EIS for the Program. (The press release includes a link to the complaint.)

Court decisions in West Virginia v. EPA (E.D. N.D.), and Kentucky v. EPA (E.D. Ky., 6th Cir.)

On April 12, following the decision in February in Texas v. EPA, (which affected Texas and Idaho, noted here), the North Dakota district court issued an injunction against the Biden Administration’s Clean Water Act regulations covering 24 more states. In addition, a March 23 opinion barring a similar challenge in the Kentucky district court was reversed by the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals on April 21, which granted a stay of implementation. (There lots of links in the article.)

In case you haven’t been keeping up, there’s a summary provided here:

- The 2015 Obama WOTUS attempted to expand the types of waterways under federal protection. Various states successfully sued to stop its implementation.

- The Trump Navigable Waters Protection Rule reduced the number of waterways under federal protection. It was implemented in 2020 and was repealed by a federal judge in 2021.

- The Biden 2023 WOTUS rule (now being litigated) returned the U.S. to a definition put in place during the Reagan administration and observed until 2015.

These cases are backing up behind a pending Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA, which will determine whether the 9th Circuit applied the proper test for determining whether wetlands are “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act.

Notice of intent to sue

On April 12, the Center for Biological Diversity notified the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service of its intent to sue for reducing critical habitat for two endangered snakes (the narrow-headed and northern Mexican garter snakes) by more than 90% from what it originally proposed to protect these species found in riparian areas. The Forest Service provided substantial comments on the original proposal, including that proposed critical habitat would affect numerous livestock grazing allotments on the Tonto National Forest. Critical habitat would be designated there and on the Gila, Apache-Sitgreaves, Prescott and Coconino national forests and BLM lands. The news release contains a link to the notice, and additional background is provided here.

New lawsuits

On April 17, Protect the Public’s Trust, which describes itself as an unincorporated association dedicated to restoring public trust in government, filed lawsuits against the Department of the Interior and the BLM for failing to meet Freedom of Information Act requirements to provide documents involving communications between agency officials and Somah Haaland, who is the daughter of Deb Haaland, the Secretary of the Interior. Somah Haaland has lobbied lawmakers as a media adviser for the Pueblo Action Alliance in support of a drilling moratorium around Chaco Culture National Historical Park in northwest New Mexico, and the request focuses on a movie about the protection efforts. The FOIA request was made on January 2.

(Family ties seem to be important to some these days; Hunter Biden comes to mind. Here’s an example of how more transparency might play out in such situations.)

Preliminary injunction granted in Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Mont)

On April 24, the district court enjoined the Knotty Pine Project on the Kootenai National Forest. The project would add 3.76 miles of road to the road system, 1.2 miles of temporary road construction, 35 miles of road maintenance, and 4.04 miles of road storage, and would include commercial harvests on 2,593 acres, non-harvest fuel treatments on 4,757 acres, precommercial thinning on 2,099 acres, and 7,465 acres of prescribed burning. The court said the agencies failed to adequately account for the harm to grizzly bears in the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem Recovery Zone from illegal roads when they authorized the project. The judge pointed out that the forest plan said any road found to have illegal use would be considered an open road for that year, so such roads should be considered in the calculation of open roads relative to compliance with forest plan road density requirements. The article includes a link to the opinion. Plaintiffs provide additional background here.

Court decision in Murphy Company v. Biden (9th Cir.)

On April 24, the circuit court upheld the expansion of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument made by President Obama in January 2017 against a challenge by timber interests. The court found that the expansion did not violate the Oregon and California Lands (O&C) Act. Cascade-Siskiyou is the only national monument in the nation specifically established to protect biodiversity. “In rejecting Murphy’s lawsuit, the Ninth Circuit today definitively concluded that conserving O&C Lands for their ecological values is consistent with the law,” said Susan Jane Brown, senior attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center. (The news release contains a link to the opinion.)

On April 24, the Supreme Court turned away five appeals by oil companies of lower court decisions that determined that the lawsuits seeking damages for climate change belonged in state court, a venue often seen as more favorable to plaintiffs than federal court. The lawsuits were filed by the state of Rhode Island and municipalities or counties in Maryland, Colorado, California and Hawaii.

Notice of intent to sue

On April 25, the Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, Appalachian Voices, Appalachian Mountain Advocates, Greenbrier River Watershed Association, and Kanawha Forest Coalition notified the Forest Service of their intent to sue related to the Forest Service’s approval of a road use permit authorizing SF Coal Co. to haul coal through the Monongahela National Forest, and related road reconstruction work. They claim that the Forest Service failed to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service regarding the effects on listed species and critical habitat in the Cherry River watershed, as well as NEPA violations. (The press release includes a link to the notice.)

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. D.C.)

On April 25, three conservation groups sued the Department of the Interior for failing to respond to a rulemaking petition to phase out oil and gas extraction on federal public lands, and a subsequent notice of intent to sue. The petition was submitted in January, 2022. The Administrative Procedure Act requires federal agencies to initiate rulemaking or provide a substantive response to rulemaking petitions within a reasonable timeframe. This lawsuit alleges that the administration’s failure to respond to the petition constitutes an unreasonable delay given the urgency of the climate crisis. (The press release includes a link to the complaint.)