Char’s post today is written in support of Change.org’s Blog Action Day, which this year is focused on water.

The monsoonal rains this summer came down so hard, so fast, that when they finally stopped, much of Pakistan was inundated.

No one doubts but that the speed and amount of rain overwhelmed the capacity of the land to absorb it all; the surging floodwaters, and the devastation they wrought, were a direct consequence of nature’s clout.

But humans had a distinct and heavy hand in the stunning devastation: for the past decade or more, Taliban fighters in the northwestern Swat Valley ignored Pakistan’s environmental regulations with every swing of their axes: “Employing termite-like efficiency,” the Los Angeles Times reports, “the militants felled and carted away vast swaths of Himalayan cedar, blue pine and oak, leaving mountainsides dotted with stumps.” They ripped out the timber to fund their political agenda and military campaigns that have so unsettled the region. Just as consequential is the denuded terrain they left behind; local farmers and Pakistani environmentalists are convinced that these illegal harvests contributed significantly to the floodwaters’ overwhelming force. Observed Ghulam Akbar, director of the Pakistan Wetlands Program: “Deforestation played a tremendous role in aggravating the floods. Had there been good forests, as we used to have 25 years back, the impact of flooding would have been much less.”

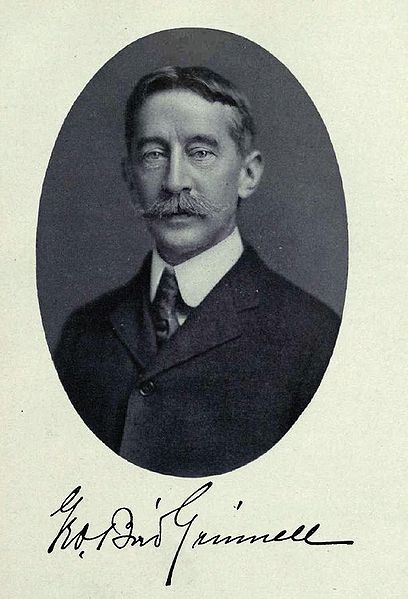

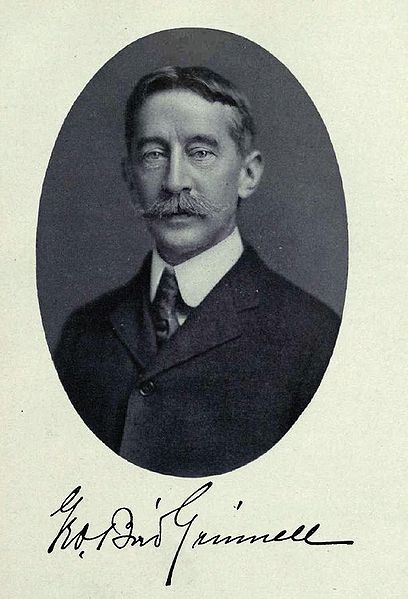

Akbar’s assertion of a tight link between environmental devastation and downstream flooding, and the related claim that maintaining forest cover would have mitigated the resulting damage, is not just an early twenty-first-century argument. It also was central to the creation of a powerful environmental movement in nineteenth-century America. One of its key architects was George Bird Grinnell,

a shrewd rhetorician and skilled organizer, who through his bully pulpit as publisher of Forest and Stream transformed how his fellow citizens conceived of their place in and responsibility for the landscape that sustained them.

Consider his seminal 1882 editorial, “Spare the Trees,” (page 19, here) a brilliant articulation of the ineluctable connection between water and forests. Speaking to his audience—which consisted of hunters and anglers, conservationists, politicians, and scientists—Grinnell challenged them to stop what he called “tree murder.” To succeed in this struggle, however, required them to appreciation the complex interactions between resource exploitation and forested ecosystems. Regulatory action could achieve only so much, he noted: “All the protection that the law can give will not prevent the game naturally belonging to a wooded country from leaving it when it is deforested, nor keep fish in streams that have shrunk to a quarter of their ordinary volume before midsummer.” To insure the “the proper and sensible management of woodlands” Americans must think in terms of habitats, Grinnell declared, a declaration that led him to close his commentary with a succinct, bumpersticker-like refrain: “No woods, no game; no woods, no water; and no water, no fish.”

Grinnell used his words to alter the political landscape. Through his magazine columns, social connections in New York City and Washington, D.C., and backroom lobbying along the nation’s corridors of power, he helped build a political consensus around the need to protect high-country watersheds. One outcome of which was congressional legislation that in 1891 gave the president the power to establish forest reserves on the public domain in the west. Known officially as the Land Revision Act of 1891, it granted the chief executive the authority to “set aside and reserve…any part of the public lands wholly or partly covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not.” Under its provisions, President Benjamin Harrison declared upwards of 13 million acres to be protected forests, the first of which was the Yellowstone National Forest; his successor, Grover Cleveland, added another five million. What is striking about the acreage they set aside is where it was located. Although the 1891 Act did not specify which lands qualified—outside of its claim that they have some kind of growth on them—those these two presidents designated were wrapped around and along mountainous watersheds. Grinnell’s claims had achieved legislative sanction.

They secured even greater authority six years later when Congress enacted what is now known as the Organic Act of 1897. It resolved a critical set of related questions about which the 1891 law had been silent: if some public lands became forest reserves, what were they reserved for? How, if they were to be managed, would they be managed? The new act answered these queries: it gave the Secretary of the Interior the authority “to improve and protect the forest within the reservation,” with a particular goal in mind: “securing favorable conditions of water flows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States.” Note that water flows preceded timber supplies, that the regulation of forest-cover in watersheds was the legislation’s preeminent concern.

The dynamic link between water and forests received even greater impetus with the passage of the Weeks Act of 1911. Initially proposed in the 1890s in response to intense logging in New Hampshire’s White Mountains,

and to similar depredations within the southern Appalachians, it took nearly 15 years for the legislation to clear Congress.

One reason for the delay was that the bill for the first time would grant the president the ability to use public funds to purchase private lands, a power that its opponents declared to be unconstitutional. They also rejected the proponents’ demands that the president use the power of the purse to protect the aesthetic qualities of the lands then under an axe-attack. Snorted Speaker of the House Joe Cannon: “Not one cent for scenery.” (yes, this is the Cannon for whom the Cannon House Office Building was named- sf).

Chastened but unbowed, conservationists revised their tactics and rhetoric, ripping a page from the George Bird Grinnell playbook: they wrote countless editorials and delivered innumerable speeches that explicitly tied cutover mountainsides to the flashfloods that ripped through industrial cities lining the banks of the Merrimack River that rose out of the White Mountains; they circulated innumerable photographs that illustrated these and other damaging ramifications of unrestrained logging in North Carolina and New England’s northern tier.

This is actually the 1936 Flood, but this is emblematic of the flooding that routinely surged down the Merrimack River, and which conservationists and business leaders were convinced was a partial consequence of heavy logging in the White Mountains.

And they redrafted what would dubbed the Weeks Act, named for its savvy floor manager, John W. Weeks,

a successful banker then representing a suburban district outside of Boston. The new version made no mention of the preservation of landscape beauty, as is captured in the legislation’s official (and leaden) title:

AN ACT TO ENABLE ANY STATE TO COOPERATE WITH ANY OTHER STATE OR STATES, OR WITH THE UNITED STATES, FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE WATERSHEDS OF NAVIGABLE STREAMS, AND TO APPOINT A COMMISSION FOR THE ACQUISITION OF LANDS FOR THE PURPOSE OF CONSERVING THE NAVIGABILITY OF NAVIGABLE RIVERS

Nothing could have been more utilitarian and yet nothing less would have persuaded Speaker Cannon to allow the legislation to come to the floor for a vote. It passed, and on March 1, 1911, President William Howard Taft signed the Weeks Act into law. With his signature, the national-forest system became fully national in fact, and watershed protection became the unifying policy mandate.

That concerns over water and watersheds were the driving agents behind the crafting of early U. S. environmental regulation may be a boon to contemporary Pakistani conservationists. Here’s hoping that they can turn the recent disastrous floods into a powerful campaign for the rigorous protection of upstream forests.

Char Miller is director and W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College, Claremont, CA. He is author of the award-winning Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism and editor most recently of Cities and Nature in the American West and River Basins in the American West.