I hadn’t realized NRCS had this program.. here’s the link.

CEQ Uses First Street’s “Wildfire Risk Maps” Instead of US Government Maps in EJ Screening Tool- Why?

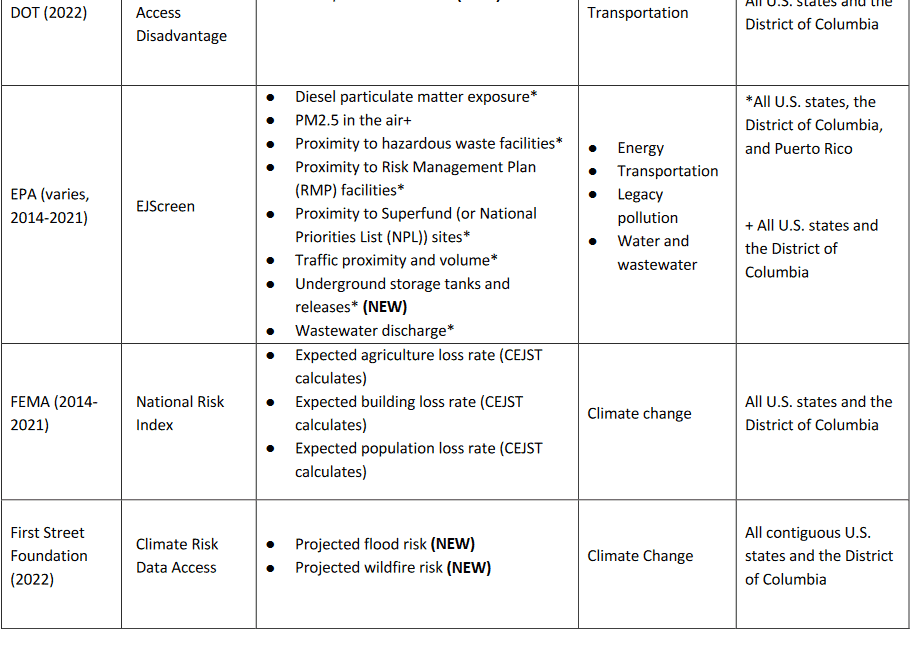

There are two current tools (at least) one by CEQ and one by EPA. We’ll look at EPA’s in another post. Both of them refer to the CEJST, which is:

Federal agencies will use the CEJST for the Justice40 Initiative. It will help them identify disadvantaged communities that should benefit from the Justice40 Initiative. The Justice40 Initiative seeks to deliver 40% of the overall benefits of certain Federal investments to disadvantaged communities. These investments relate to seven areas: climate change; clean energy and energy efficiency; clean transit; affordable and sustainable housing; the remediation and reduction of legacy pollution; the development of critical clean water and wastewater infrastructure; and training and workforce development. This task of delivering the benefits of hundreds of Federal programs to disadvantaged communities is challenging. It requires fundamental and sweeping changes to the ways in which the whole Federal government operates

So that’s why it’s important to us. It will be a tool to disperse government funds, so .. should be looked at quite carefully. There are a variety of ways to do this. This one combines data sets collected for other purposes with intentions of “justice” so certainly deserves some scrutiny.

First, CEQ used First Street’s questionable Wildfire Risk Maps instead of the USG’s own. Why? We’ve critiqued those maps here.

If you read their v. 1.0 technical support document, table 2 on page 18, it stands out among the other sources. If CEQ needs wildfire risk data, wouldn’t it make more sense to ask the wildfire agencies… and if it doesn’t work for CEQ for some reason… explain why and ask the agencies to analyze that? I think it’s really quite puzzling, given the extra transparency and quality that government data requires (e.g. the Data Quality Act). And taking public comment and so on.

Anyway, that was a surprise!

If you think it’s a bad idea to use their data, or have other improvements to suggest, they have a couple of places on the website to give feedback.

****************

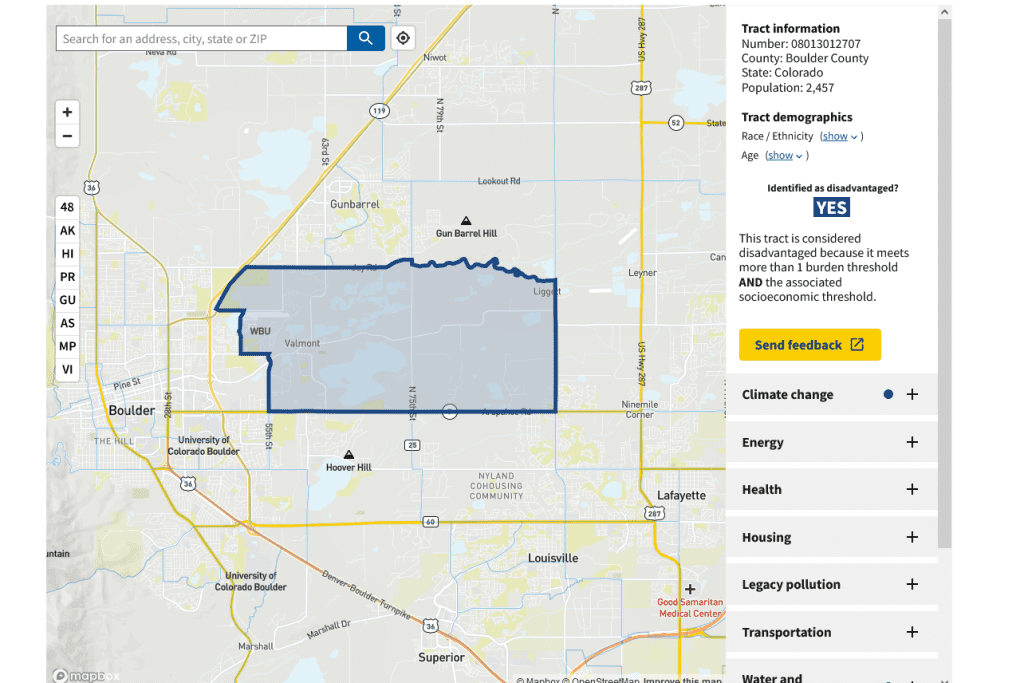

Here’s what I did.. check out some area you know. (they use census tracts so that leads to straight lines where you can imagine more of a gradient).

And then on the right side, you can check out why it is “overburdened and underserved.”

For example, I picked one next to Boulder, Colorado an area I’m familiar with.

It explains:

This tract is considered disadvantaged because it meets more than 1 burden threshold AND the associated socioeconomic threshold.

Expected building loss rate

Economic loss to building value resulting from natural hazards each year 95thabove 90th percentile

- Expected population loss rate Fatalities and injuries resulting from natural hazards each year 96thabove 90th

And

Low income People in households where income is less than or equal to twice the federal poverty level, not including students enrolled in higher ed

71st above 65th

Housing cost

Share of households making less than 80% of the area median family income and spending more than 30% of income on housing 55th not above 90th

Wastewater discharge

Modeled toxic concentrations at parts of streams within 500 meters 96thabove 90th

Also: High school education

Fish and Wildlife Service Proposes ESA Listing for California Spotted Owl

From Greenwire (subscription) today… Lots of data and background in the Federal Register notice.

The Fish and Wildlife Service proposed distinct Endangered Species Act protections Wednesday for two California spotted owl populations that have long provoked heated policy and political debate.

In a kind of split decision, the agency is proposing that the owl’s Coastal-Southern California population be listed as endangered while the larger Sierra Nevada population would receive the more lenient designation of threatened.

…

The proposal is not out of the woods yet. In addition to finalizing a listing decision after what will be a lively public comment period, the Fish and Wildlife Service has yet to designate critical habitat that could conceivably spread across millions of acres.

Public Lands Litigation Update – through February 15, 2023

Now that we are no longer receiving the Forest Service’s updates, my goal is to provide a summary of relevant lawsuits twice a month. (Did you know that “bi-monthy” can mean either twice a month or every other month? That’s pretty useless.) I’ll try to include a link to the court document in or via the header when I’ve got that.

My sources of information are pretty hit-or-miss, so some of them may be a little late. Still, if it looks like I missed something you think should be included, let me know about it. (There’s one of those included here – thanks!)

(Another) court decision in Friends of the Clearwater v. Probert (D. Idaho)

This court had (for the second time) previously granted summary judgment on Plaintiff’s challenge to a travel planning decision in 2017 allowing motorized use of the Fish Lake Trail trail in a Recommended Wilderness Area on the Clearwater National Forest, finding violations of elk habitat standards in the forest plan, and “minimization” requirements of the Travel Management Rule. On December 1, the court vacated the exception in the travel plan for that particular trail, meaning that the trail would no longer be designated as open to motorized use, and therefore such use would be prohibited. The court found “no reasonable justification” for the more than seven-year failure to comply with the first remand order in 2015, in particular with no end in sight for completing the revised forest plan. It established a June 1, 2024 deadline for completing the remand and it required interim reporting to the court.

- Oil and gas leasing delays

Intervention: State of Wyoming v. U. S. Department of Interior (D. Wyo.).

In December, Wyoming and two industry trade groups challenged the Bureau of Land Management’s decision to not hold lease sales during parts of 2021 and 2022. Plaintiffs claim the agency has an “unwritten policy” pausing leasing and want the court to order the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the BLM to hold lease sales every three months across the west. On February 9, 17 conservation organizations were granted intervention (per the motion attached to this news release). An earlier case in Wyoming held that the federal government has broad authority to postpone sales to address environmental concerns (see Western Energy Alliance v. Biden (D. Wyo.)).

Intervenor briefing in State of North Dakota v. U. S. Department of Interior (D. N.D.)

In January, North Dakota also sued the BLM for postponing oil and gas leases and not issuing them every three months, mimicking the Wyoming lawsuit and its own similar lawsuit in 2021. This press release includes a link to a brief filed by conservation group intervenors on February 9.

Court decision: Dine´ Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment v. Haaland (10th Cir.)

On February 1, the circuit court ruled on the adequacy of an “EA Addendum,” prepared after a previous loss in district court, and 81 individual Environmental Assessments. The circuit court held that the BLM again violated NEPA by failing to account for the impacts – including health effects – of toxic air pollution from oil and gas drilling and fracking, and the impacts of added carbon pollution to the climate. The court also ordered a halt to new drilling permits. (The article linked above includes a link to the decision.)

The district court had upheld the decision, and this reversal by the 10th Circuit is the first time it has ruled in favor of citizen groups on these issues. This article explains the reasoning:

Arguably the most noteworthy element of the ruling was that the BLM could, and indeed should have compared the volume of greenhouse gasses emitted by permitted wells to the levels budgeted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

On appeal, the BLM had claimed that “incremental contribution to global (greenhouse gasses) from a proposed land management action cannot be accurately translated into effects on climate change globally or in the area of any site-specific action.”

“(The BLM) is not free to omit the analysis of environmental effects entirely when an accepted methodology exists to quantify the impact of GHG emissions from the approved (Applications for Permits to Drill),” the court ruled.

The court did not see this preapproval as an unlawful predetermination, given the BLM’s willingness to revoke permits if the wells were found to violate the final environmental analysis.

Partial court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. Minn.)

On February 1, in the latest iteration of this case, the district court dismissed parts of a claim that the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Army Corps of Engineers should have reinitiated consultation on the land exchange that removed the site from the Superior National Forest, and on a Clean Water Act permit. It allowed the case to proceed with this claim, but limited it to determining if reinitiation was necessary to address the recent decline in the northern long-eared bat population, and alleged changes in the mine proposal. (There are also additional claims remaining in this case.)

New lawsuit: Wilderness Watch v. Halter (D. Minn.)

On February 3, Wilderness Watch sued the Forest Service for failing to implement a 2015 settlement agreement where it agreed to study and correct excessive motorized towboat use to shuttle canoes farther into the Superior National Forest wilderness. (The article includes a link to the complaint.)

Court decision in Bartell Ranch v. McCullough (D. Nev.)

On February 6, the district court held that the BLM complied with NEPA for the Thacker Pass mine, and met its tribal consultation obligations, but violated FLPMA as it relates to the approximately 1300 acres of land that Lithium Nevada intends to bury under waste rock because BLM did not first make a mining rights validity determination as to those lands. The court did not vacate the decision while BLM makes this determination. (A link to the opinion is provided at the end of the article.) We most recently discussed this case here.

On February 7, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent to sue the Fish and Wildlife Service for unlawfully delaying final listing decisions for species it had proposed for listing: Peñasco least chipmunks, Mt. Rainier white-tailed ptarmigans, South Llano Springs moss, bog buck moths, cactus ferruginous pygmy owls, tall western penstemons, four distinct populations of foothill yellow-legged frogs, and eight freshwater mussels. The notice also opposes the delay in finalizing critical habitat protection for Humboldt martens. The marten was discussed here, and the yellow-legged frogs here. More on the pyramid pigtoe is here.

The Penasco least chipmunk was proposed for listing as endangered in 2021 with proposed critical habitat. The chipmunk is native to the Sacramento and White Mountains in south-central New Mexico in and around the Lincoln National Forest, but remains only in the White Mountains, with about half of the habitat in a wilderness area. In its listing proposal, the Fish and Wildlife Service said it was especially threatened by recreational activities in the area, and livestock grazing is also implicated.

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. Fla.)

On February 8, the National Park Service was sued for failing to prepare an EIS or to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service before removing land-use restrictions to allow construction of Miami Wilds waterpark, hotel, and retail development, where 17 threatened or endangered species may occur, including some critical habitat. Miami-Dade County received these lands in the 1970s and 1980s from the U.S. Department of the Interior and NPS through conveyances that required the county to use and maintain the land for public park or public recreational purposes, along with other terms, covenants, and restrictions. The NPS decision at issue, an agreement with Dade County, would transfer those restriction to lands outside of this project area. (The article has a link to the complaint.)

The Minnesota Court of Appeals has ruled that construction of a new wood products plant requires preparation of an EIS and reconsideration of effects on two public wetlands. The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe challenged the decision by the Cohasset City Council because of perceived threats to wild rice in Blackwater Lake and two eagle nests, and an imperiled fern — called the goblin fern — in its Chippewa National Forest old-growth habitat. (The Forest Service was apparently not a party to the lawsuit.)

We have previously discussed the use of southern forests to produce wood pellets for energy generation. Last fall, a Georgia judge allowed a case to proceed with claims that the permit for the Spectrum Energy pellet mill in Adel, GA violated the Civil Rights Act because the Georgia Environmental Protection Division discriminated against minority residents of a small town by approving an air pollution permit for manufacturing wood pellets.

The BLM is offering a $2,000 reward for information leading to a conviction of anyone responsible for graffiti vandalizing the Moccasin Mountain Dinosaur Tracksite located southwest of Kanab.

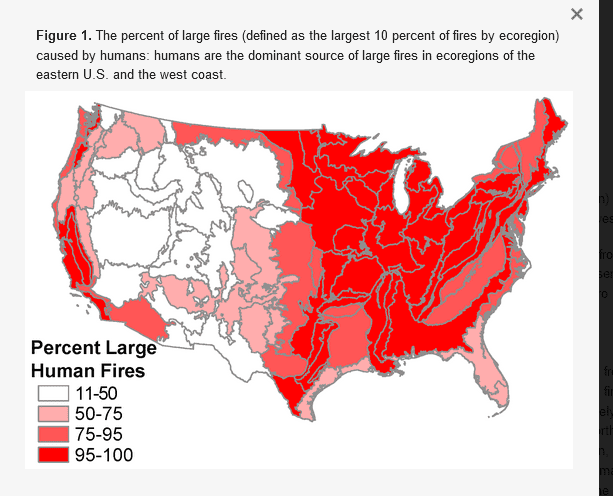

Should Smokey Bear Move to TikTok?

Les’s article about Smokey Bear signage reminded me of this (2018) Nagy et al. paper. I read lots of climate media and papers and it is a given in some that “climate causes increased wildfires.” As we know, climate (or changes in weather over time) can certainly influence fire behavior, but so can fuel conditions, suppression strategies and tactics, and …. ignitions. This seems obvious, and more easily dealt with than decarbonizing global energy production, so it seems like something scientists would want to look at. We have seen fires start from power lines, people driving in dry grass, and people doing what appear to be really stupid things to celebrate events, and a variety of other causes. Many of these ignition sources have been the targets of behavioral change efforts via media, lawsuits or criminal charges. It seems like a likely topic for social scientists to look at.. what are all the human caused sources? What has worked in practice to reduce them?

Does anyone know of such studies?

From the paper:

Large Fire Seasonality

The seasonal expansion of large wildfires in the spring in the eastern U.S. (Figure 3a) was similar to the pattern of fires of all sizes [5], with many large human-caused fires occurring earlier in the year than large lightning-caused fires (Figure S6) and outside of the lightning fire season (Figure S7). Given the strong correlations previously identified between large fires and climate [3,18,34,49,56], we expected large fires across the U.S. to be more likely during dry, hot summer months in the western U.S. In the eastern U.S., the seasonality of large human-caused fires was highly correlated with the seasonality of human-caused fires of all sizes across most eastern ecoregions (Figure 4). These results suggest that seasonal climate does not play an important role in facilitating large fires in the East. Instead, ignition pressure is the primary driver of large fires in these ecoregions. This finding is consistent with [57], who showed that human ignitions are a more important driver of fire than climate in the eastern U.S. In the northwestern U.S., the seasonal correlation between large fires and all fires was lower (Figure 4), suggesting that climate conditions may play a more important role in facilitating large fires here. Nonetheless, even in ecoregions of the intermountain west where climate is known to influence large fires [2,12,56], human ignitions explained a substantial portion of the seasonal pattern of large fires (r > 0.66; Figure 4). This finding suggests that ignition pressure, and human expansion of ignitions [5], plays a much larger role in influencing large fires than previously thought.

The Fastest Staple Gun in the West?

I soon fancied myself “the fastest staple gun in the West” for the way I kept fresh Smokey Bear posters displayed all over the district.

My greatest fire prevention ally as a Toiyabe National Forest fire prevention guard was Smokey Bear. That’s backward, of course. I was Smokey’s ally, and only one of many throughout the United States.

Smokey had been America’s “forest fire preventin’ bear” for nineteen years by the time I became the Bridgeport Ranger District fire prevention guard in 1963. With his famous “Only you can prevent forest fires!” tag line, Smokey had become the most recognized symbol in advertising history.

I was proud to be on Smokey’s team, and used the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Program materials I ordered each year to the fullest. I soon—albeit secretly—fancied myself “the fastest staple gun in the West” for the way I kept fresh Smokey Bear posters displayed on well-maintained peak-roofed signboards—all strategically located, by the way, in accordance with a fire prevention sign plan—all over the district.

In addition to stapling these colorful posters to these signboards, I installed and maintained the signboards—crafted in the ranger station’s shop by fire crew members on days they were not working in the field—all over the district. And so, in addition to its pumper unit and fire tools, my patrol rig was equipped with a post-hole digger, tamping bar, and other sign structure installation tools as well as a five-gallon bucket of brown stain and paint brushes to keep both newly installed as well as older signage looking sharp.

Smokey Bear posters were also displayed in Bridgeport’s public buildings, stores, restaurants, motels, and gas stations as well as at resorts and businesses throughout the district. A supply of Smokey Bear comic books for children met while on patrol was always in the patrol truck along with free national forest maps—yep, they were free in those days—and other information for public distribution. Every campfire permit issued on the district had a small Smokey Bear fire prevention reminder stapled to it.

All of these efforts were, of course, supplementary to the dozens of personal fire prevention contacts with forest visitors and users which I made every day while on patrol.

Although I could not back up my belief with statistics that all these fire prevention efforts actually prevented any wildfires, the district ranger and the fire control officer and I were convinced they did.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.

For the First Time, Genetically Modified Trees Have Been Planted in a U.S. Forest: NY Times

This article was a total blast from the past for me.. I organized a joint meeting with SAF, ESA, and Pew Agbiotech on forest tree biotech lo these twenty years ago.

This article was a total blast from the past for me.. I organized a joint meeting with SAF, ESA, and Pew Agbiotech on forest tree biotech lo these twenty years ago.

Most forest products companies have not been interested in carrying these kinds of investments (for one thing conifers are harder to grow from culture) with unknown risks over sawtimber rotations.

Nevertheless, it could be that carbon markets upend these traditional economies. Conceivably every year these trees soak up more carbon than your average poplar (or whatever the carbon is measured against), it could be making some money. Even if they ultimately die.. early, or get sick, or eaten by bugs, or various other predators, and start producing less than the average pop. (that’s why I can’t really get my head around many tree carbon market programs). Or maybe not? Note the caption to the photo says “the company has started marketing credits” based on things that haven’t happened yet and could be reversed.

But the landowner in this story is planting a mix of species, so his risk is minimal..his idea is simply to get the hybrid poplars to the same size faster. If that doesn’t work, the other trees will just soak up the carbon. Also, mixing species are handy from the unknown future angle, as forest economists have long understood vis a vis markets and pests, but is also true for unknown climate change.

They’re also being planted alongside native trees like sweet gum, tulip trees and bald cypress, to avoid genetically identical stands of trees known as monocultures; non-engineered poplars are being planted as experimental controls. Ms. Hall and Mr. Mellor describe their plantings as both pilot projects and research trials. Company scientists will monitor tree growth and survival.

Understatement of the week for reforestation practitioners:

“They have some encouraging results,” said Donald Ort, a University of Illinois geneticist whose plant experiments helped inspire Living Carbon’s technology. But he added that the notion that greenhouse results will translate to success in the real world is “not a slam dunk.”

This one gave me a chuckle. I seem to recall a research proposal mentioned low lignin loblolly pine for easier (and less chemical-using) pulping. The old “floppy tree” proposal.

The problem with these approaches has been that researchers want to do something (like get $ for sequencing, or make money in carbon markets). So they dream up ideas and hype them. So environmental groups listen, and think that the hype will really happen (plantations of floppy trees or GE hybrid poplars everywhere!) and get worried, hyping the hype. Meanwhile, the rest of us just yawn and carry on.

That same year, Ms. Hall, who had been working for Silicon Valley ventures like OpenAI (which was responsible for the language model ChatGPT), met her future co-founder Patrick Mellor at a climate tech conference. Mr. Mellor was researching whether trees could be engineered to produce decay-resistant wood.

From floppy trees to decay-resistant wood in only 30 years!

In a field accustomed to glacial progress and heavy regulation, Living Carbon has moved fast and freely. The gene gun-modified poplars avoided a set of federal regulations of genetically modified organisms that can stall biotech projects for years. (Those regulations have since been revised.) By contrast, a team of scientists who genetically engineered a blight-resistant chestnut tree using the same bacterium method employed earlier by Living Carbon have been awaiting a decision since 2020..

“You could say the old rule was sort of leaky,” said Bill Doley, a consultant who helped manage the Agriculture Department’s genetically modified organism regulation process until 2022.

Why would gene-gunning (without Agrobacterium genes involved) be OK? Well, the source of APHIS’s regulatory authority was that Agrobacterium is a plant pest, and thereby subject to the Plant Protection Act. No Agro, no authority. Gene gunning = no authority. As in this sorghum letter I found online:

Because domesticated sorghum is not a plant pest or listed as a federal noxious weed, the genetic elements used to generate TRSBG101B Transgenic Sorghum are all sourced from fully classified organisms, and the transformation process does not introduce any plant pest DNA components, there is no scientifically valid basis for concluding that TRSBGlOlB Transgenic Sorghum is, or will become, a plant pest within the meaning of the Plant Protection Act (PPA).

Ceres therefore asserts that under current regulations, TRSBG101B Transgenic Sorghum is not a regulated article within the meaning of 7 CFR §340.1 because it does not satisfy any of the regulatory criteria that would subject it to the oversight of the USDA’s Animal Plant Health and Inspection Service (APHIS).

There are so many different ways of working with DNAs and RNAs today that the regulatory system must be almost unimaginably complex. It must be difficult to keep up with the technologies.

And from fellow forest geneticists:

Forest geneticists were less sanguine about Living Carbon’s trees. Researchers typically assess trees in confined field trials before moving to large-scale plantings, said Andrew Newhouse, who directs the engineered chestnut project at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. “Their claims seem bold based on very limited real-world data,” he said.

Steve Strauss, a geneticist at Oregon State University, agreed with the need to see field data. “My experience over the years is that the greenhouse means almost nothing” about the outdoor prospects of trees whose physiology has been modified, he said. “Venture capitalists may not know that.”

Dr. Ort of the University of Illinois dismissed such environmental concerns. But he said investors were taking a big chance on a tree that might not meet its creators’ expectations.

“It’s not unexciting,” he said. “I just think it’s uber high risk.”

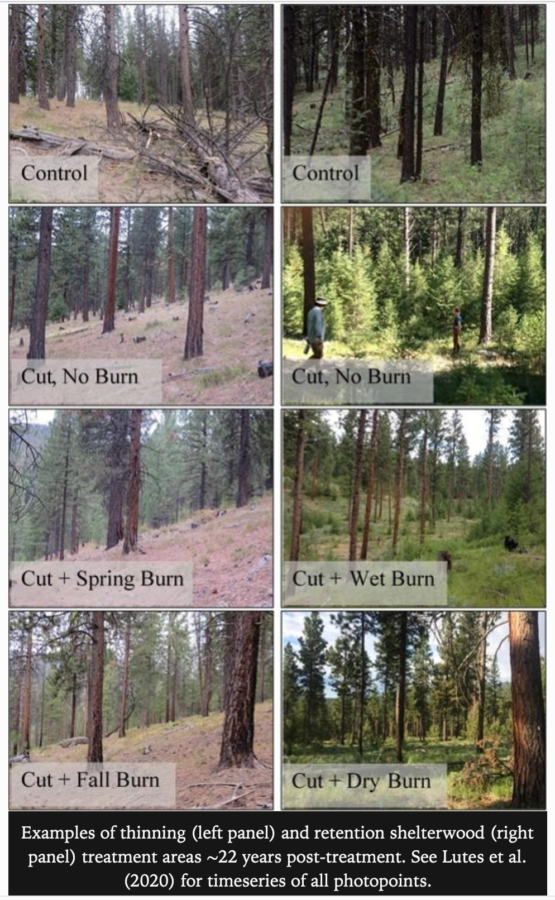

Does Thinning Work for Wildfire Prevention? High Country News Weighs In

https://twitter.com/PSICC_NF/status/1625974301714427905/photo/2

Several people, including WUI residents doing mitigation work, brought this High Country News article to my attention.

****************************

Some of my pet peeves include redefining English words and making up abstractions, simply because those behaviors tend to increase disagreements just by misunderstandings. So here we go:

Thinning is not logging. To its opponents, thinning is a form of “silviculture by stealth,” as wildfire historian Stephen Pyne put it. Pyne, however, says thinning is more like “woody weeding.” Logging, he explained, harvests large, mature trees over large areas, while thinning mostly removes small trees. Logging makes money; thinning almost always costs money.

In plain old Helms Dictionary of Forestry, thinning is a cultural treatment made to reduce stand density. Now, Pyne, is a fire expert for sure, but Steve just posted about the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie project that, according to the Courthouse News article:

The Forest Service approved between 2,000 to 3,300 acres of commercial thinning and 1,060 acres of noncommercial thinning.

Now in plain English “commercial” means that you can make money from the stuff. So conceivably the old way of thinking “must be traditional sized sawtimber” to make money.. it could also be commercial firewood or chips or material for engineered wood products or biochar or….

Please everyone, let thinning mean thinning and commercial mean commercial!

*****************

I hadn’t seen this open-access Commentary by Jones et al, called “Counteracting Wildfire Misinformation” but maybe someone posted it previously. Short and worth a read.

A continually changing media ecosystem presents challenges and opportunities to mitigating the spread of misinformation. Here, journalists and news organizations have a weighty responsibility, playing a critical and often insufficient role in reducing misinformation.

More later on that.

********************

And here we go….

Thinning should be followed by prescribed fire. “If you don’t follow it up with the right fire, then it’s worthless, and in many cases may have made it worse,” said Pyne. Thinning and prescribed burning are the one-two punch that will knock out many severe wildfires. Prescribed fires do have drawbacks: They are complicated to plan and execute, they dump unwanted smoke on communities, they’re subject to litigation, and in rare instances they can spark destructive burns. Nevertheless, they are sorely needed, and without them, thinning rarely succeeds.

Thinning by itself is “worthless” and it “rarely” succeeds. It seems to me that it’s more complicated than that. Certainly thinning without removing the material could make things worse. But what fuels practitioner would design a project that doesn’t remove the thinned material? The discussion in the 10 common questions paper (cited in the HCN article) is more nuanced.

Thinning from below reduces ladder fuels and canopy bulk density concurrently, which can reduce the potential for both passive and active crown fire behavior (Agee and Skinner 2005). For instance, Harrod et al. (2009) found that thinning treatments that reduced tree density and canopy bulk density and increased canopy base height significantly reduced stand susceptibility to crown fire compared to untreated controls.

…

Some studies show that thinning alone can mitigate wildfire severity (e.g., Pollet and Omi 2002, Prichard and Kennedy 2014, Prichard et al. 2020), but across a wide range of sites, thin and prescribed burn treatments are most effective at reducing fire severity (see reviews by Fulé et al. 2012, Martinson and Omi 2013, Kalies and Yocom Kent 2016).

When we talk about “prescribed fires” , pile burning is not the image that springs to mind of “prescribed fire”. Even though it is prescribed fire.. When I looked around for a definition of all the kinds of prescribed fire, I thought this was a pretty good explanation from the BLM. And pile burning is not as complicated to plan and execute as other kinds. Fuels folks across the west have been doing it for years.

I find this discussion a little more confusing than it needs to be.

*************

Kelly Andersson of Wildfire Today had a piece today on this..

Opponents of thinning and other fuels treatment methods really need to take a look at the history of Lick Creek in Montana. The Lick Creek Demonstration – Research Forest studies were established back in 1991 in western Montana to evaluate tradeoffs among alternative cutting and burning strategies aimed at reducing fuels and moderating forest fire behavior while restoring historical stand structures and species compositions.

Firefighters and numerous studies over many years credit intensive forest thinning projects with helping save communities like those recently threatened near Lake Tahoe in California and Nevada, but dissent from some environmental advocacy groups still roils the scientific/environmental community. An Associated Press story out of Sacramento in October of 2021 noted that environmental advocates say data from recent gigantic wildfires support their long-running assertion that efforts to slow wildfires have instead accelerated their spread. “Not only did tens of thousands of acres of recent thinning, fuel breaks, and other forest management fail to stop or slow the fire’s rapid spread, but … the fire often moved fastest through such areas,” Los Padres ForestWatch, a California-based nonprofit, said in an analysis joined by the John Muir Project and Wild Heritage advocacy groups.

********************

It sounds like some groups say.. (1) thinning with burning doesn’t work (as the above statement in the AP story)

others (2) thinning plus mechanical removal doesn’t work without burning the smaller material left over, but that depends on site-specific conditions.

I ran across this paper by Cram et al. from NM and Arizona that said, for example, increasing surface fuels may have advantages in terms of suppression tactics.

Furthermore, when forest canopies are opened up via mechanical means, fine understory fuels can be expected to increase. The silver lining in increased fine surface fuels is the improved potential and efficiency to use back-burns ahead of a wildland-head fire, not to mention a key ecological role in the symbiotic relationship between fire and pine forests. Backfires burning through fine surface fuels are more effective and efficient in burning out understory fuels as compared to a closed canopy forest with a deep, but compacted, litter understory. Estimates of fireline intensity indicated that hand and dozer lines would have been effective containment techniques in treated stand.

IMHO this topic could really use some reporting by interviewing fuels and suppression folks and dig into the specifics of their experiences in different parts of the country. Quoting the usual academic and interest suspects is not adding much value.

Feds Respond in Eastside Screens Lawsuit

This article is free from Law360 after you register.

Feds Cite ‘Scientific Support’ For Policy Shift On Tree Removal

Excerpt:

Law360 (February 14, 2023, 3:33 PM EST) — The U.S. Forest Service is defending its decision, in early 2021, to scrap a decades-old restriction on cutting down old and large trees in the Pacific Northwest, arguing that a more flexible standard is needed to ensure that forests in the region can survive a growing number of wildfires.

Responding on Friday to a lawsuit filed by environmental activists, the Forest Service cast its old regulations — prohibiting the removal of trees that measure over 21 inches in diameter — as outdated and overly rigid.

The federal agency said its new standard, adopted in January 2021, provides a flexible approach that emphasizes protecting old trees in the Pacific Northwest but allows the removal of certain tree species that aren’t fire tolerant and crowd out ecologically beneficial species. That policy shift, the Forest Service said, “satisfies all statutory requirements and enjoys strong scientific support.”

“The weight of scientific consensus counsels the Forest Service to mitigate [wildfire] threats by actively managing forests to favor more historically prevalent, fire tolerant species,” it argued. “But that change is impossible if the Forest Service cannot cut any competing fire intolerant species over 21 inches in diameter.”

Federal authorities adopted the 21-inch prohibition as part of a 1994 series of timber regulations known as the Eastside Screens, which applied to 7.9 million acres of national forests in the Cascade Mountain Range of Oregon and Washington.

Read more at: https://www.law360.com/articles/1575462/feds-cite-scientific-support-for-policy-shift-on-tree-removal?copied=1

Ninth Circuit considers effects of ‘temporary’ logging roads in national forest

That’s the title of a Courthouse News article. Subtitle: “If forest roads can exist as long as 20 years, are they really temporary?”

“On appeal, North Cascades argues nothing within the Forest Service’s contracts with intervenors Skagit Log and Construction, Hampton Tree Farms and Hampton Lumber Mills guaranteed that roads would be closed at the end of its use. As such, the Forest Service violated the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan because there will be a net increase in road mileage within the project area for as long as 20 years.”