I thought I’d pull out some topics from the NFF/FS Wildfire Crisis Strategy Roundtables executive summary for more discussion.

Let’s pull this out:

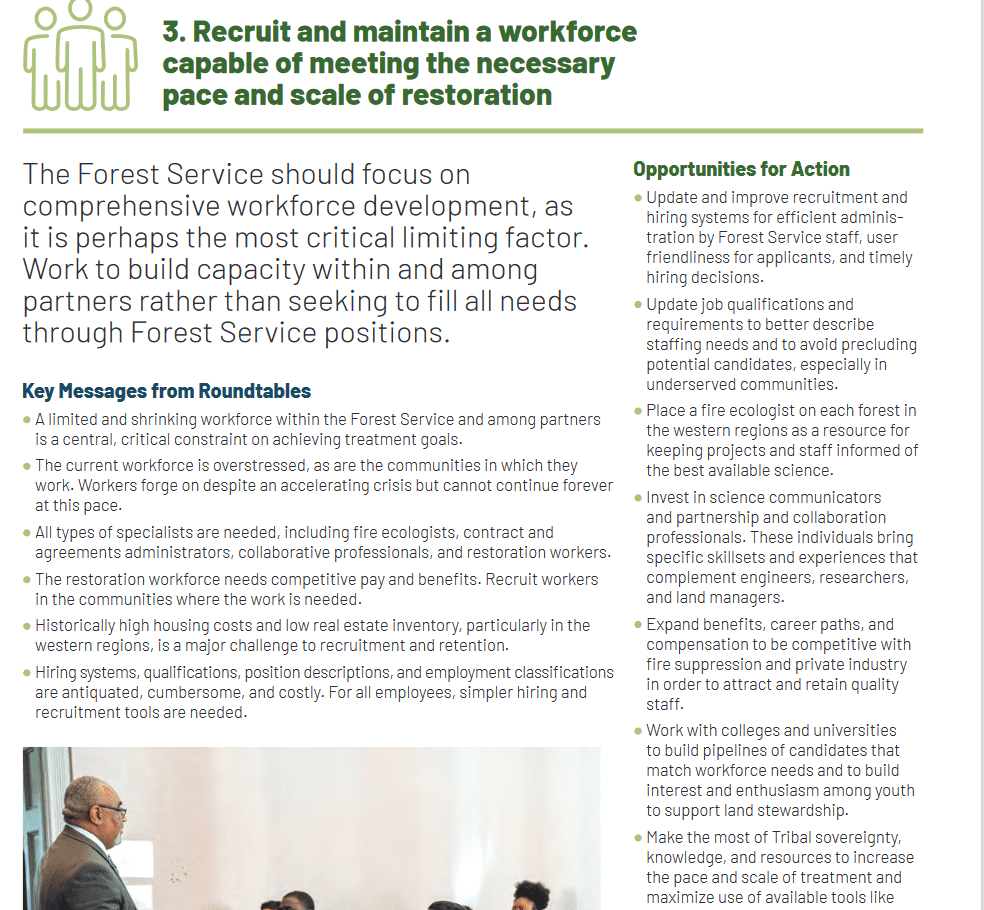

• Work collaboratively to include a range of values into the criteria that guide prioritization and planning for restoration, fuels treatment, and management, such as:

• Fire risk reduction

• Source-water protection

• Habitat resilience

• Recreation and public access

• Local and regional economies

• Underserved, vulnerable, and fire-impacted communities

• Public health and water and air quality, both rural and urban

• Protecting cultural and heritage resources

• Guide investments through a lens of equity and serving fire-vulnerable communities.

. Recruit workers and share leadership with Tribal and rural communities.

• The definitions of “underserved” and vulnerable communities are not well understood or consistently interpreted.

For those of you who have been around awhile, you might remember that agencies were told they couldn’t prefer local residents for contracts because that was against the FARS. And certainly preferences for local people in federal hiring would be against all kinds of rules. Sharing leadership with rural communities.. well, we still discuss that, although perhaps we’d agree on sharing leadership with Tribes?

I’m not surprised that words like “underserved” and “vulnerable” haven’t been defined.

There is something that happens when people in DC use nice-sounding words, and someone else has to interpret them (see also “sustainability” “equity” various forms of justice “environmental” “climate” “social” and numerous other abstractions). Each agency can develop its own interpretation, NGOs have theirs, and it can lead to all kinds of unnecessary discussion and befuddlement.

I thought perhaps the Biden Administration would have a helpful definition of underserved, especially since in his first day in office President Biden signed Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.

It is therefore the policy of my Administration that the Federal Government should pursue a comprehensive approach to advancing equity for all, including people of color and others who have been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality.

Here are the definitions in the EO:

Sec. 2. Definitions. For purposes of this order: (a) The term “equity” means the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.

(b) The term “underserved communities” refers to populations sharing a particular characteristic, as well as geographic communities, that have been systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic, social, and civic life, as exemplified by the list in the preceding definition of “equity.”

I have to admit, I found this confusing, because:

“consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment” could mean one of (at least) two things. One (1) is today and forward “from now on, everything will be fair just and impartial of everyone”. The other (2) is trying to be fair in the sense of say, Aspen and Breckenridge already finished acres of fuel treatments, and so to be fair, fuel treatments around poorer communities should be brought up to the same level.

I think many of us think that (2) would be the “most fair” approach; but that’s not exactly what the definition says.

An example of a pragmatic approach, Colorado State for its wildfire grant programs has a map of the low income areas, which have to provide less of a match than other areas. Is that fair? Or would it be fairer to focus $ only on low income areas until some level of equity had been established? How inequitable have state grants been so far? Or even more broadly, does anyone keep track of the actual amount of money plugged into wildfire mitigation grants by county or zip or whatever scale? That would be feds, state, counties, NGO partners, landowners? Or it fairness by total acres treated and not by funding levels?

Now, fairness is a very difficult and complex topic in itself. But definitions may also require some kind of data collection, and I’m not sure that information is available. Maybe the first step would be analyze current inequities, and then take specific steps to equalize them.

Finally, in the EO definition, I thought the combination of “persons who live in rural areas” and “members of religious minorities” .. there is one state in particular with a high percentage of people who satisfy both of those criteria.

And yet President Biden also reinstated and added acres to Bears Ears Monument – I’m not sure how equitably this was perceived by folks in Utah. Can you have “fair just and impartial treatment of individuals” without involving them in how those decisions are made? Or in other words, should representatives of all the underserved be involved in determining how to achieve equity for them?

Lots to think about, and it’s not surprising that the people who are supposed to be carrying out this quest for justice have asked for more clarification.