Here is the Forest Service summary: Litigation Weekly July 01 2022 Email

Other links are to court documents.

Court decision in Apache Stronghold v. U.S Department of Agriculture, (9th Cir.)

On June 24, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court of Arizona’s decision denying plaintiff’s motion for a preliminary injunction against the Oak Flat Resolution Copper land exchange on the Tonto National Forest. The case concerns the alleged violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the Free Exercise Clause of the Constitution’s First Amendment, and a trust obligation imposed on the United States by the 1892 Treaty of Santa Fe between the Apache and the United States.

Court decision in Mountain Communities for Fire Safety v. Elliott (9th Cir.)

On June 21, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals denied petition for rehearing en banc submitted by plaintiffs. The case concerns the use of categorical exclusion 6 (for timber stand and wildlife improvement with commercial thinning) for the Cuddy Valley Project on the Los Padres National Forest, which was summarized here.

Court decision in Earth Island Institute v Nash (E.D. Cal.)

On June 16, the Eastern District of California issued a favorable decision to the Forest Service. This case concerns the combined efforts of the State of California, U.S. Housing and Urban Development, and the Forest Service with regard to the 2016 Rim Fire Recovery and Restoration Project on the Stanislaus National Forest and the California Biomass Project. The court determined the 2016 Rim Fire Project activities had already been completed and no new environmental impact statement (EIS) was needed by the State of California, and the use of the relief act funding was permissible.

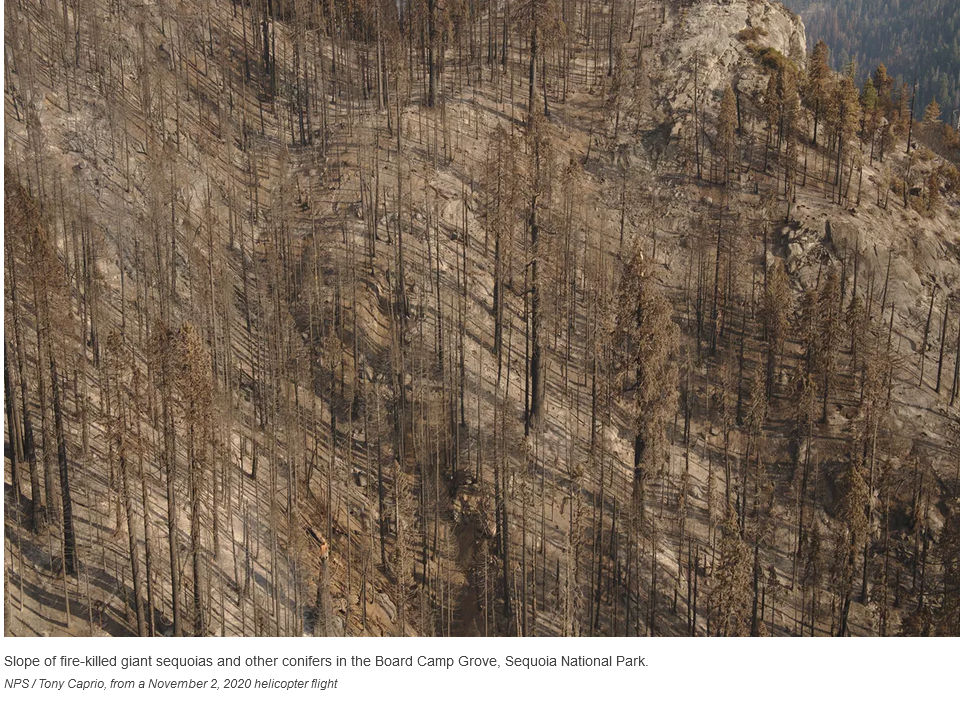

New case against the National Park Service: Earth Island Institute v. Muldoon (E.D. Cal.)

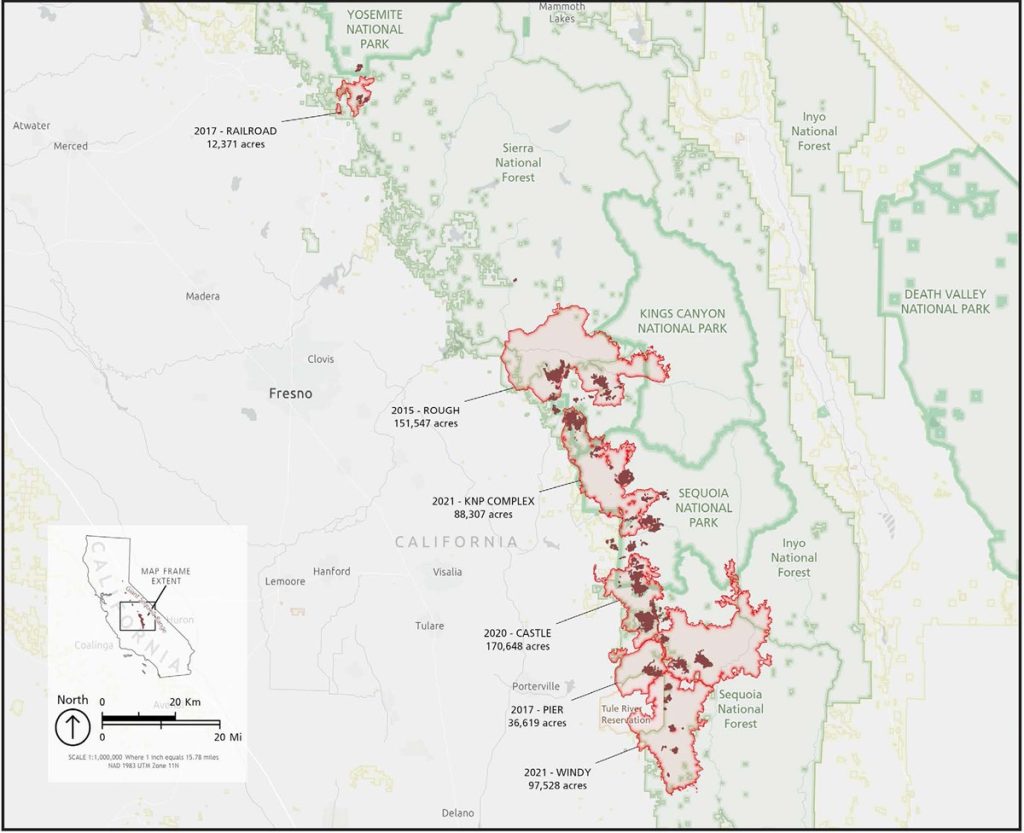

On June 13, the plaintiff filed a complaint against the National Park Service regarding its Biomass Removal and Thinning Project (for removal of hazardous fuels) to protect Sequoias in the Yosemite National Park. The plaintiff alleges the Agency improperly used a categorical exclusion (CE) in authorizing the project.

BLOGGER’S BONUS

The last “weekly” we received was dated June 10, so here’s some other things that have happened since then.

Court decision in WildEarth Guardians v. Bail (E.D. Wash.)

On June 7, the district court upheld the Forest Service’s authorization of domestic sheep grazing on allotments within the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. The court relied on a 2014 amendment of the Federal Land Management and Policy Act that allowed grazing to continue pending completing NEPA analysis for permit renewals to hold that, “Because the Forest Service has not completed its final analysis, there is no final decision for this Court to review at this time.”

- R6 eastside old growth amendment: Hells Canyon complaint

New case: Greater Hells Canyon Council v. Wilkes (D. Or.)

On June 14, six environmental organizations filed a complaint against the “Forest Plans Amendment to Forest Management Direction for Large Diameter Trees in Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington,” which replaces the 1995 “Eastside Screens” amendment with guidelines allowing more harvesting of large trees on six national forests. Plaintiffs allege NEPA violations of inadequate effects analysis and failure to prepare an EIS, and NFMA violations from lack of an administrative objection process and failure to follow procedures for “significant” changes in the forest plans. We discussed this here.

New case against the BLM: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Department of the Interior (D. D.C.)

On June 15, the Center for Biological Diversity and WildEarth Guardians filed a complaint challenging at least 3,535 applications for permit to drill (“APDs”) for oil and gas in New Mexico’s Permian Basin and Wyoming’s Powder River Basin in violation of NEPA, ESA, and FLPMA and those statutes’ implementing regulations. (The article includes a link to the 254-page complaint.)

Court decision in Natural Resources Defense Council v. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (9th Cir.)

On June 17, the circuit court ruled that the EPA’s determination that glyphosate (the active ingredient in the herbicide Roundup) was not likely to be carcinogenic was not supported by substantial evidence. It also held that EPA’s registration review decision under FIFRA was an “action” that triggered the ESA’s consultation requirement, which the agency admitted it did not comply with. The court did not vacate the decision while further analysis occurs as required by FIFRA by October 2022. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)