John asked the question last week “what is AGW?” in the context of my throwing in acronyms to posts without explaining them. This post is my rather-long answer to why I sometimes use the term to indicate the human-caused part of climate change (anthropogenic global warming). I also don’t use it sometimes, I’m sure inconsistently and confusingly, because some windmills are too big for even me to tilt at (!). In this post I’ll talk about the terminology, and in the next post I’ll follow it through a recent real-world series of events.

But first I need to introduce the concept of the Climate Hydra. It’s the mix of conscious decisions by a variety of actors that lead to how climate change is framed and portrayed by scientific communities, the media, and politicians.

But let’s start with the globally validated clump of experts. Here’s how the IPPC SREX defines climate change:

Climate change

A change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings, or to persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use.

Note that this definition involves both human and natural causes and isn’t just about greenhouse gases (GHGs) but also about land use changes, which we know something about, at least for forests.

However, as commonly used, it can mean only the human-caused part.

Weird, huh? “Climate change” has become a shorthand for only a part of climate change. And the natural part kind of disappears from view. You know, natural parts like glaciation, El Niño and La Niña, and so on. It would be a bit like defining “forest regeneration” as natural and planted, and then only talking about planted. You would miss the bigger picture.

I don’t know why this is, and I’m not assuming any bad intentions from anyone. It could be just a natural part of the Hydra ecosystem. My current hypothesis is that it’s too hard for journalists to explain every time, and it’s definitely too hard to keep up with the details of attribution studies for specific parameters and places, so it has just fallen by the wayside. Using AGW (albeit inconsistently) is my own way of saying “natural variation exists also.”

How do scientists determine the proportion of each? I’ll explain that in a later post. I’m sure it won’t surprise you that it is both complicated and contested. You’d think that there would be a great deal more written about it since it is so key to building trust.

Again, I don’t know how much variation in what aspects of climate, where and for what time periods, is natural and how much is human-caused. But I don’t think it’s all human-caused. So let’s take a relatively simple example of something that we are all familiar with, and that has become a poster-child for the Climate Hydra: wildfire.

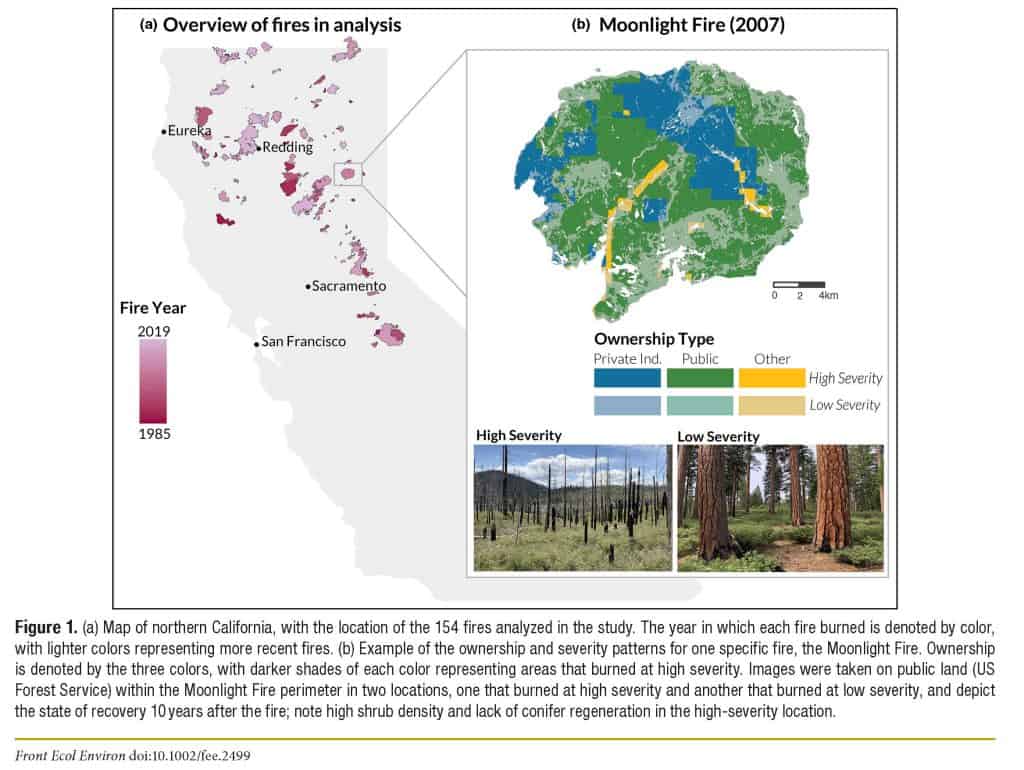

There have been changes in temperature and weather patterns and drought through time, but also fire suppression, more human-caused ignitions, and large-scale fires where we didn’t have the resources to put them out when they were small, so they grew big. And different suppression strategies, and more people living and recreating (in California, but not so much in Kansas). And grass fires are different from forest fires, and so on.. Just understanding ignition sources and how they’ve changed over time would be huge. How can you tease apart the impacts of all these different factors? And what are we trying to model for.. acres burned? Bad environmental consequences? Bad social-economic-health consequences?

What if we agreed…”bad” fire impacts are influenced by :

a) weather

b) fuels

c) ignitions (human and weather)

d) suppression resource availability, strategy and tactics

e) human-caused climate change (of course these would affect weather (sooner) possibly ignitions (by lightning) and ultimately fuels)

f) natural variation climate change (think of El Nino and La Nina and longer term changes) (like human-caused, these affect weather sooner, and then will circle back to changing a b and c.)

g) luck (other fires at the same time; weather luck, convenient stopping points, resource availability and so on), or what we scientists call “stochastic factors”.

Maybe you can think of others. And we can do a simple model.. would we still have bad fire impacts without e? Of course, so it’s a factor- but one of many. And there were bad fire impacts (at least large fires) in our country before human-caused climate change started, so that fits.

When someone says “the average temperature in my county in July has gone up 6 degrees in the last 20 years due to climate change” it makes it sound as though we know all of that was due to human-caused climate change. What IPCC does with this is that it calls the difference “detection” of change (any cause) versus “attribution” which is usually done with models with and without human influences on climate (usually GHG’s and land use).

In conversations, I sometimes hear “how can people observe this difference (warmer temperatures, drought) and “deny” climate change?” Well, they may not be “denying” climate change at all. They may be saying “I don’t know how much is due to humans and how much is due to natural variation.” Or for something more complicated than a temperature measurement, like wildfires, they might be thinking “there are factors a to g and I don’t know how important each one is. I do know if we stopped producing GHGs today (highly unlikely), we would still have problematic wildfires.” Or they might simply distrust attribution models. Or their Grandma may have told stories about droughts in the 1930’s that seemed worse than today. Rather than call someone a denier, we might get further by engaging in these conversations.

One of the essential missing links in climate discourse is an honest acknowledgement of all the related uncertainties. It seems like the Climate Hydra has us stuck on “if we acknowledge them, people won’t want to do anything.” But others (and I) feel “if you’re not honest about uncertainties, people won’t trust you, even you are certain.” So this climate action strategy may be shooting itself in the proverbial foot.