By Martin Nie, University of Montana

A defining characteristic of these initiatives is their shared goal of securing greater certainty and predictability in national forest management. This manifests itself in numerous ways.

First, it explains why some groups have chosen to pursue national forest-specific legislation, and in other cases, why some groups have formalized their relationships with the USFS through MOUs and decision making protocols.

Second, most initiatives I reviewed are seeking more permanent types of land designations than that provided by forest planning processes or roadless rules that are viewed as being more tenuous. Consider the following for example:

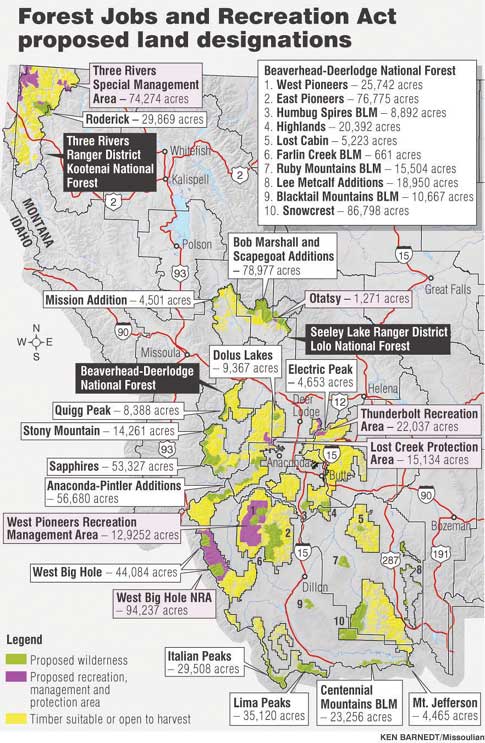

- Senator Tester’s S. 1470, the Forest Jobs & Recreation Act (FJRA): It seeks not only to designate wilderness and special management areas, but to also codify defined “stewardship areas” where timber harvesting and restoration goals are given priority. (These stewardship areas are defined by making reference to the relevant Forest Plans and those areas designated as suitable for timber production). Tester’s Bill also provides greater certainty regarding management of ORVs. In some places, access is permanently restricted, and in others, long-term access is guaranteed.

- The proposed Rocky Mountain Front Heritage Act: It would designate more than 300,000 acres as the “Rocky Mountain Front Conservation Management Area” with a set of customized purposes and restrictions. Chief among these are restrictions placed on motorized usage, as the proposed bill would codify decisions made in the area’s travel plan.

- The Northeast Washington Forestry Coalition Blueprint: It divides the Colville National Forest into three management zones: responsible management areas, restoration areas, and wilderness areas.

Third, these groups hope to take some intractable issues off the table with some finality. Finding permanent protections for inventoried roadless areas is the most common example. But in some cases, this applies to old growth as well. Senator Wyden’s Bill (S. 2895) is most direct in this regard, as it prohibits the cutting of live trees exceeding 21 inches in diameter (with some exceptions). Old growth is also addressed in the Colville and Fremont-Winema MOUs, as both seek to protect and restore old forests. And in Arizona, debate over a diameter cap is front-and-center in the Four Forests Restoration Initiative.

Fourth, several of these initiatives are seeking ways to generate a more certain and predictable flow of timber.

- The most controversial example is provided by Senator Tester’s FJRA. The bill mandates that 70,000 acres on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge and 30,000 acres on the Kootenai are to be “mechanically treated” by the USFS over the next ten years.

- Senator Wyden’s Eastside Oregon Bill also seeks “to create an immediate, predictable, and increased timber flow to support locally based restoration economies.” To kick-start this goal, Wyden’s bill requires interim mechanical treatments that produce an average of 100,000 acres a year for three years. Wyden’s bill is different than Tester’s in that mechanical treatments are to “emphasize saw timber as a byproduct.”

- The two MOUs also share the goal of creating more certainty for the timber industry, but they go about things a bit differently. On the Colville, for example, the Coalition’s designation of a responsible management area, along with its MOU, provides a more predictable land base from which timber may be harvested. The Lakeview Federal Sustained Yield Unit also “promote[s] the stability of forest industries, of employment, of communities, and of taxable forest wealth, through continuous supplies of timber.” The Unit does so through its MOU with the USFS, as it commits the Fremont-Winema “to the extent permitted by and consistent with all applicable laws and land use plans, offer a minimum of 3,000 treatment acres per year” outside the Stewardship Unit, and a minimum of 3,000 acres per year within it.

Securing a more predictable flow of timber is often explained by making linkages between local economies/sawmills and forest restoration goals. Several of these initiatives define the problem similarly: landscape-level forest restoration requires the harvesting of small diameter trees, and that means the necessity of some sustainably-scaled, locally-rooted forest products industry. And for that industry to survive, or to make the requisite capital investments (in say, small diameter processing equipment), it needs greater assurances about timber supply.

Also relevant to this theme is the widespread interest in stewardship contracting. In most of the initiatives I examined, stewardship contracting is a central part of restoration strategies. The tool is seen by some people as a means to secure more predictable dollars for restoration work, money that stays on a particular national forest and is not sent back to Washington, D.C., and thus not subject to the highly uncertain congressional appropriations process. (Stewardship contracting will be discussed again in the context of restoration and funding).

Next Post: What to make of this search for certainty and stability? What does it have to do with forest planning?

So it sounds like people are tired of arguing about

1) land use designations (roadless being a subset of this)

2) travel management

I wonder what makes the areas that have developed PBBAs different from others that share these frustrations? Are they more frustrated than others or just more able to organize to deal with their frustrations?

Certainty of timber production was one of the reasons the Sustained Yield Units were established (in the 1944 Act), so that’s an idea that’s been around a long time. Again, I wonder what makes those areas (other than the Sustained Yield Units – I mean areas where people have taken action on PBBAs recently) interested in PBBAs more than other areas – if industry in those places is about to make a major investment and needs greater than average certainty? Or if they more sociopolitical horsepower to deal with their frustrations?