Our previous discussion here, which started out as a post on how the 2001 Roadless Rule does allow utility and hydro corridors, transmogrified into discussing salvage on the Biscuit Fire in SW Oregon. But the comment format didn’t do justice to Foto’s photos, so here they are.

Month: March 2011

ENS Article on Planning Rule Forum- Expecting Too Much From a Planning Rule?

Here it is, with some quotes below.

But Defenders of Wildlife says the draft rule ignores scientific recommendations on wildlife diversity protection.

Rodger Schlickeisen, president and CEO of Defenders of Wildlife said, “President Obama holds the future of our nation’s forests and wildlife heritage in his hands as his administration crafts the new rule governing national forest policy. His administration has an opportunity to lead us into a new century of forest management. Unfortunately, in its present form, the draft rule promises much more than it delivers, leaving the future of wildlife on 193 million acres of land belonging to the American people mostly up to chance.”

The nonprofit Sierra Forest Legacy, based in California, says, “At first reading, we note that the single most important measurable protection to ensure protection of wildlife, afforded by the 1982 regulations, has been removed entirely.”

The group is referring to the “Viability Standard” at 219.19 in the 1982 regulations, which states, “Fish and wildlife habitat shall be managed to maintain viable populations of existing native and desired non-native vertebrate species in the planning area.”

The 1982 Viability Standard continues, “For planning purposes, a viable population shall be regarded as one which has the estimated numbers and distribution of reproductive individuals to insure its continued existence is well distributed in the planning area.”

“In order to insure that viable populations will be maintained, habitat must be provided to support, at least, a minimum number of reproductive individuals and that habitat must be well distributed so that those individuals can interact with others in the planning area,” the Viability Standard concludes.

The Sierra Forest Legacy warns, “Without such clear direction for protecting wildlife, the new planning rule represents a step backward, suggesting that the agency has abdicated its long held responsibility for maintaining our national forests as the last refuge for the continent’s increasingly imperiled wildlife.”

Marty Hayden, vice president of policy and legislation with the public interest law firm Earthjustice, said, “The Forest Service’s draft rule shows that the Obama administration understands and supports the basic concepts of how to protect the indispensible watersheds on our National Forests, but, by failing to adopt enforceable standards, it falls short of guaranteeing the protections our country desperately needs.”

And

But conservationists are not convinced the draft planning rule will protect waters and wildlife. “It’s not just the streams, rivers, and wetlands outside my back door and yours that remain in trouble. Waters across the nation are threatened by a legacy of serious harm from forest and grazing land use on National Forest lands,” said Dr. Chris Frissell, director of science and conservation for the Pacific Rivers Council.

“This history is a principal reason why our native trout and salmon are in such tough shape today, and this means the new planning rule will need to take firm steps forward, not backward, to ensure the health of our watersheds and fisheries is restored,” he said.

“The rule still needs, among other things, clear direction to reduce harm to watersheds by removing and restoring forest roads, an established national minimum streamside buffer zone, and development and compliance with firm standards protecting waters and aquatic life,” said Dr. Frissell. “Good intentions are great, but in an ecosystem as complicated as a watershed, standards and a commitment to real monitoring are necessary to ensure that the agency’s actions in fact protect and restore the environment. This draft rule doesn’t get us there. ”

On the proposed rule’s treatment of science, Dr. Frissell said, “The rule still needs language to say it’s the Forest Service’s job to both bring the best available scientific information to the table and to actually use it as the basis for planning, and to implement and monitor the measurable standards that are necessary to ensure water resources and watershed health are in fact being protected and restored.”

I don’t know what Dr. Frissell means by using science as “the basis” for planning. But I also ran across testimony of Dr. Pielke, Sr. on climate change this week.

Decisions about government regulation are ultimately legal, administrative, legislative, and political decisions. As such they can be informed by scientific considerations, but they are not determined by them. In my testimony, I seek to share my perspectives on the science of climate based on my work in this field over the past four decades.

For those of you unfamiliar with his work, he describes other forcings than CO2 in a way accessible to the public (or at least, me) in his testimony here.

News (?) Article on Planning Rule Forum

This is from the “Public News Service” whose mission is:

The Public News Service (PNS) provides reporting on a wide range of social, community, and environmental issues for mainstream and alternative media that amplifies progressive voices, is easy to use and has a proven track record of success. Supported by over 400 nonprofit organizations and other contributors, PNS provides high-quality news on public issues and current affairs.

Last year the Public News Service produced over 4,000 stories featuring public interest content that were redistributed several hundred thousand times on 6,114 radio stations, 928 print outlets, 133 TV stations and 100s of websites. Nationally, an average of 60 outlets used each story. This includes our bilingual content, which is growing rapidly as we strengthen relationships with Spanish media outlets.

In addition, about one-third of our stories are picked up by national networks and redistributed across the country.

Of course if we were looking for a plain old news story, they might have interviewed people with more than one point of view.

Forest Service Planning Rule Gets Lukewarm Reception

March 11, 2011

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Conservation groups are giving a lukewarm reception to the proposed planning rule that guides U.S. Forest Service policy and will affect much of Oregon when it becomes final.

The agency held a forum on Thursday in the nation’s capital to discuss a draft of the rule, which some say lacks enough “teeth” to protect water quality and wildlife. Concerns were also voiced about whether the focus on monitoring and adaptive management of public land can work for an agency that has been chronically underfunded. Chris Frissell, director of science and conservation for the Pacific Rivers Council, attended the forum.

“The Pacific Northwest, under the Northwest Forest Plan, is somewhat of an exception. But prior to that, and then pretty much everywhere else, the Forest Service has had great difficulty getting any sustained monitoring program off the ground and has not been able to keep it funded. Congress just hasn’t put money into those things.”

Watershed management is another concern, Frissell says, because the rule does not include buffer zones to limit some activities along streams and lakes. The current rule has been in place since 1982, and has been controversial over the years. If there’s one word for the new proposal, Frissell says, it’s “cautious” – and people interested in the various issues affected are taking note.

“It’s pretty much the full slate of issues – everything from restoration to forest fuels treatment and fire management, to timber. And in fact, a lot of the interest groups around that whole table had the same concerns, about uncertainty and vagueness in the rule and what the rule delivers for their interests.”

The draft planning rule is open for public comment until mid-May, and comments can be made online. Two forums will also be held March 25 in Portland to discuss the rule, both at the Sheraton Airport Hotel.

The draft rule, including comment instructions and a related Forest Service blog, are online at www.fs.usda.gov/planningrule.

Not Seeing the Forest for the Trees

If I were a visitor from another planet, who having read some of the recent posts to this blog, wanted to understand what all the fuss about things like “viability” is about, I might look to the Forest Service homepage for guidance. There I would learn that “The mission of the USDA Forest Service is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.” Pretty straightforward so far. Looking for more of what these things called “national forests” are all about, I would learn that the agency’s “Motto” “Caring for the Land and Serving People” means, among other things, “Protecting and managing the National Forests and Grasslands so they best demonstrate the sustainable multiple-use management concept.” I would get confused though because I read that the mission also includes things like “Listening to people and responding to their diverse needs in making decisions.” And although I would agree that that is an absolutely essential thing to do, I wouldn’t be able to find anything in any law that says that is part of the agency’s mission. You might say that I was nit-picking, but fortunately we don’t have nits on my home planet.

Reading on through the Forest Service “Vision” wouldn’t help either. I might find lots of nice statements about “a caring and nurturing environment” where “employees are respected, accepted, and appreciated”, but I wouldn’t find anything about how the agency thinks the national forests should look in the future if it did a good job at carrying out its mission.

If I did a bit of Googling, I could learn that some pretty smart scientists have been thinking about new and better ways to plan and monitor and that they presented some of these ideas at the Forest Service Science Forum. [Full disclosure– I wouldn’t actually have to Google it since I was the principle author of the final report for the forum]. Some of these scientists pointed out, however, that “. . . while science can help inform decision-making processes, it is most appropriately applied first in a context of shared agreement on the agency goals that will drive management decisions.”

In the absence of shared agreement in the form of a clearly articulated and widely shared vision for the future of the national forests, even an alien can see why a number of conservation organizations insist that the proposed rule doesn’t go far enough to require actions to ensure important things like species viability.

Despite the trees, that forest is evident even to a visitor from outer space.

21st Century Problems- Hazard Tree Removal

Interesting headline…couldn’t find a link to the project easily, so no photo.

Judge Protects Forest From Forest Service

By SONYA ANGELICA DIEHNSAN JOSE (CN) – A federal judge granted a preliminary injunction to protect imperiled species on the remaining 600 miles of a $1 million roadside-clearing project in Central California’s Los Padres National Forest. U.S. District Judge Lucy H. Koh granted Los Padres Forestwatch’s requests to protect the National Forest from the U.S. Forest Service.

Judge Koh found that the Forest Service’s failure to seek input from the public or other agencies “flies in the face” of environmental laws designed to ensure an open process.

The project involves removing trees and vegetation along 750 miles of forest roads in the Los Padres National Forest, to reduce fire risks and other potential hazards.

Judge Koh found that the Forest Service had failed to seek public input and consult other agencies over its plan, despite its own biologists’ findings that it could affect threatened and endangered species such as the Smith’s blue butterfly and seacliff buckwheat.

The nonprofit environmental group says the forest hosts 26 species protected under the Endangered Species Act.

After an internal process, the Forest Service in 2009 issued a categorical exclusion exempting the project from environmental review.

The Forest Service accepted a $1.1 million proposal for the clearing a year ago.

A Forest Service biologist had recommended measures to protect imperiled species, which Los Padres Forestwatch later demanded in its lawsuit.

These included a biologist being present to review planned clearing areas for the presence of imperiled species, and avoiding clearing along rivers or streams, and during nesting or breeding seasons.

Koh ordered the Forest Service to do so, in issuing a limited injunction allowing the project to proceed. The Forest Service also must provide weekly progress reports to the environmental group.

The conditions apply to the remaining 585 miles of the project.

Deja Vu, All Over Again

While researching back issues of High Country News for a future post, I ran across this article..from 1995.. the year the original Toy Story was the #1 movie and Microsoft introduced Windows ’95.

– From the September 04, 1995 issue by Erik Ryberg

While reform of the Endangered Species Act captures headlines across the West, some conservationists say an equally important law is also in danger.

It is the National Forest Management Act, or NFMA, which has governed watersheds, soils and wildlife for nearly two decades. Forest Service officials now propose wholesale changes in the regulations that implement the 1976 law.

“The Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act get all the press, but really it’s the NFMA that’s been holding our forests together,” says Jennifer Ferenstein of Missoula’s Alliance for the Wild Rockies.

Ferenstein says the law’s current regulations specifically direct the Forest Service to maintain viable populations of native species throughout their ranges and protect water quality and soil productivity. “No other public-land law is so sweeping and so straightforward,” she says.

But the Forest Service, in a 35-page explanation, contends that these rules are difficult to understand and contain too much “language without real substance.” It says new rules are needed to give the agency greater flexibility, to streamline forest plans, and to allow for “adaptive management” necessary to implement ecosystem analysis.

Environmentalists fear the new regulations go far beyond streamlining.

“All the clarity in the current regulations has been removed,” says Ferenstein. “Wherever the current regulations say the agency “shall protect streams and streambanks,” or “shall provide for fish and wildlife habitat,” the proposed regulations substitute a lot of vague language about professional judgment and the need for flexibility.”

Ferenstein says when her group makes an administrative appeal on a logging project, it is almost always based on the act. “We use (it) to ensure that riparian areas are protected, to ensure that soil compaction doesn’t occur, and to ensure that regeneration needs are met,” she says. “All of that is going down the drain with these new regulations.”

Jeff Juel of the Inland Empire Public Lands Council in Spokane, Wash., says the new regulations amount to “total industrial dominion” over publicly owned forests. His group recently filed a legal challenge to a timber sale on the Kootenai National Forest, alleging the sale will threaten population viability of eight native species. The new regulations would prevent such court challenges on behalf of any species not already listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Speaking for the Forest Service in Washington, D.C., planning specialist Ann Christensen says the current regulations require her agency to perform unrealistic analyses. “The meaning of a term like population viability has evolved over the years,” she says. “Depending on the interpreter it can be beyond the grasp of anyone to implement the current regulations.”

But Kieran Suckling of the Southwest Center for Biodiversity in Silver City, N.M., says rules like the minimum viability requirement are essential. “With the current rules, you can measure the effect of Forest Service projects and hold the agency accountable for them,” says Suckling. “You can go out and count woodpeckers; you can judge the accuracy of a forest plan by acquiring data.”

The proposed rules, he says, reflect an “ethereal world with no measures and no accountability.”

Because grassroots groups across the West have used this law to shut down countless logging and grazing plans, adds Suckling, “It’s no surprise the Forest Service wants to get rid of it.”

A copy of the proposed regulations, which are scheduled to become final in early 1996, can be obtained at any forest supervisor’s office or by requesting them from the Forest Service at P.O. Box 96090, Washington, D.C. 20090.

Planning Rules, Manuals and Handbooks – a flashback

Here is a post from a short-lived blog I ran in 2005, Forest Planning Directives, about Forest Service planning Manual/Handbook rewriting. I think it may shed light on our planning rule critique as well. And it can serve as a guidepost, for the inevitable Manual/Handbook rewriting that will ensue just after the Draft Planning Rule moves to “Final.” Here it is, lightly edited:

Any role at all for NFMA Directives?

I have struggled for the last few days to better understand management and planning systems and ask myself whether we ought to keep any parts of the "interim directives." As usual I answer, No! You may find my thoughts amusing. You may find them bemusing. There is an odd chance you may find my thoughts enlightening. Here they are:

Land Management Planning as an Embedded Process

We have many processes (or systems) to help us manage the national forests and other public lands. Problem is these systems are often fractured and fragmented, and sometimes work at cross-purposes. We have tried to run our systems as pieces of a well-oiled machine. But it can’t work that way. The world is too complex for that, and sometimes politically wicked as well. A better management model is one that mimics nature, one comprised of self-organized complex adaptive systems. See Margaret Wheatley and Mryon Kellner-Rogers A Simpler Way for more.

Looking at things hierarchically, in a complex systems frame, we can see land management planning systems embedded in planning systems, embedded as part of "management systems."

Forest Service Management Systems

It proves helpful to see the map of interrelated systems that aid in adaptive management/organizational learning. Commonly recognized systems include:

- Assessment Systems

- Evaluation Systems

- Inventory Systems

- Monitoring Systems

- Planning Systems

Add to these supporting systems, like:

- Education and Training Systems

- Personnel Recruitment and Support Systems

- Budgeting and Finance Systems

- Information Technology Systems

- And so on

Now overlay all these with various "functions," like:

- Vegetation management (timber, range, etc.)

- Bio-physical resource management (soil and water, wildlife, plants, etc.)

- Fire management (suppression, pre-suppression, etc.)

- Facilities management systems

- Recreation management systems

- And so on

Finally overlay all with what we refer to as "Line Management," with about:

- 900 District Rangers, who report to

- 120 Forest Supervisors, who report to

- 9 Regional Foresters, who report to

- 1 Chief Forester

Now we can begin to get a glimpse of the complex nature of the management systems that we attempt organization with. The trick to all this is to make sure that the systems are not only complex, but adaptive and purposefully interrelated as well. No small order. And there are traps along the path we need to be aware of.

Decision Traps

Identifying systems and subsystems can either empower us or disable us. There are two traps that people commonly fall into here. First, we do not want to overly-reduce the complexity that enfolds us or we may develop overly complex systems or components in any one area, and at the same time neglect other important areas. This trap has been called "Abstracted Empiricism" or "Methodism."

Second, we may simply trap ourselves in the identification of the complex systems themselves. This trap is called "Grand Theory," where the trapped are paralyzed by their own overly-generalized identification and specification of complexity in the universe. In extreme form, this trap paralyzes people to the extent that they do not attempt any organization at all.

Interconnectivity, Dynamics, and Relationships

Traditionally we like to think of our organization as decentralized. But given law, policy, and Manual and Handbooks, etc. it is hardly decentralized.

We also traditionally think of our organization as working according to the dictates of "directives" that guide much of the action. Problem is, the directives tend not to be able to guide the workings of this (or any other) complex, adaptive, system. So what we have is a mess. We pretend to be decentralized, but that cannot be. We pretend to be directed in much of what we do, but the direction seems at best archaic, at worst unworkable from the get-go.

All the management systems are highly inter-connected. For now we will simply recognize them without pigeonholing them into some rigid structure like "plan-do-check- replan." This is not to say that we won’t keep that model in mind. Instead we don’t want to get trapped into thinking that is all we have to do. Our general approach should be mindful of our over-complexification dark side, our penchant to narrow our focus to the inner reaches of whatever box we find ourselves in and begin crafting ever-more- complex regulation, rules, technical guides, etc.

Take planning, for example. We have to plan before we develop any system or subsystem. But we can over-plan any system and ruin it. See, e.g. Henry Mintzberg, The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, 1994. In the Forest Service we have many over- planned and under-used systems. A lesson we continue to fail to learn, is that we need to design systems that can grow and develop as "users" continuously critique them and improve them. That means we have to start small, and let systems grow and develop as they are used. It also means that we have to weed out components, subsystems, and even whole systems that have outlived their usefulness. Pruning and tending are important, if unglamorous tasks in managing systems.

We need fewer teams of people to design work for other people, and more teams that design their own work and do it in ways that both improve and simplify the systems they work with. W. Edwards Deming champions such organization in his The New Economics: For Industry Government Education. Margaret Wheatley and Myron Kellner-Rogers lay out fundamental ideas and concepts on organization, information, and relationships in A Simpler Way. I recommend reading the books beginning with A Simpler Way, then moving to The New Economics, and finally for the devoted (and particularly for planning cheer-leaders) reading The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. But there is no way to practice adaptive management if we are unwilling to think about and read about ways to make it happen.

What does this mean for Manuals and Handbooks?

It means only that we had better do something very different from 18-30 feet of shelf space filled with cumbersome Manuals and Handbooks. We had better cut it all to the bare minimum. We had better take advantage of what’s out there in professional practice, and only add what must be added to help professionals work in our environment. It means The End of Bureaucracy & the Rise of the Intelligent Organization, which is also a very informative book written by Gifford and Elizabeth Pinchot. {Note Gifford is the grandson of the Forest Service’s founder.}

In this spirit, the Forest Service economists recently reduced about 100 pages of Manual and Handbook materials (FSM 1970, FSH 1909.17) to about 2 ¼ pages each for Manual and Handbook. The manual says, in essence, address social and economic context in various ways and places to help set a stage for managerial decision making. And highlight the social and economic consequence of proposed (and actual) action to the extent practical and foreseeable.

What does this mean for the Land Management Planning Manual & Handbook?

For Land Management Planning it means that we need to design and work with a subsystem that contributes to the whole rather than being parasitic on the whole. It means we need to quit thinking about controlling other systems. We need instead to think about contributing our small part to a broader whole.

First lets look at broad management systems. What might such a systems look like? What directives might guide it? The system is a complex web of multiply interrelated systems, all sharing some information with other systems while holding some information within any given system since it only adds "noise" to other systems. All systems are interrelated as well by the relationships between them, and by the relationships between those who take care of each system, and by the relationships of these people with those whose focus is broader, covering several or all systems.

Sustainability

The system is purpose driven, wandering down a path toward what many call sustainability. We know that the path is long, winding, and indeterminate. Sustainability is a vision quest. Sustainability is something that shape-shifts as we move down the path. But sustainability is also something that we are ever-mindful of. It is a goal that hovers in front of us, guiding us. Ecosystem constraints bound the path – some associated with natural and biological systems, some associated with human systems.

Long term, we are rewarded when we stay on the path toward sustainability, and punished when we stray beyond the bounds. Short term, we often blow the boundaries, sometimes by political design and sometimes by human error. Such deviations are punished, but the punishment may be felt by "contemporaneous others" or "future others." There are lags, often very long ones, in the feedback loops.

Surrounding our complex of managerial systems, and connected to them are broader-framed social systems with names like science, ethics, politics, beliefs, participation, that are part of the social/cultural environment. These systems interrelate with natural systems in the physical and biological realms.

Now let’s look at land management planning systems, embedded in ever-larger adaptive management frames.

Land Management Planning

What questions might guide our inquiry? (Similar questions might be framed for any planning)

- What is planning?

- How does it fit into adaptive management?

- What do we expect from planning?

- What if desired deliverables do not include a plan? Remember that Scenario Planning advocates and many others do not believe that the goal of planning be the production of a plan. Instead, they stress the importance of planning to rehash the past and rehearse the future.

- If we expect a plan, along with other deliverables, what do we want it to do?

- If we only want a plan to be a vision document, perchance highlighting vision over a variety of landscapes, but not making any how-to decisions, then we will answer this question much differently than if we expect a much more comprehensive, detailed plan.

Why bother with any Manual or Handbook? Why isn’t the NFMA Rule enough directive? Perchance the NFMA Rule is already too much directive, but that is a question for another time.

——————————–

2011 Update: Closely Related Posts

Why Three Planning Levels?

New Planning Rules Fails as Adaptive Management

The Frame Game

Newsbite: Alaska Roadless Decision

For those of you who follow roadless, here’s a link.

This was an interesting quote:

The Sierra Club’s Mark Rorick says that’s not the case.

“The roadless rule does not stop personal use wood permits, and it does not stop access or road-building to mines. It allows utility corridors through the roadless areas. It allows corridors for hydro. All these things that people are saying the roadless rule would stop are just not true.”

Not too long ago, in a courtroom not far away, we were in litigation about a pipeline where the plaintiffs argued that building a linear facility required the equivalent of a “road” which was not OK by the 2001 Rule. We argued the same as Rorick and won. It’s nice when we can all agree.

HCN Story on Planning Rule: New National Forest Rule Lacks Rigor

Here’s the link.

Here is a quote.

But it’s precisely that flexibility that worries Peter Nelson, federal lands director at Defenders of Wildlife. “Flexibility absent consistent guidance can lead to a variety of outcomes for water and wildlife,” he says, “not all of them good.” For instance, “the proposal directs forest managers to provide for the viability of species” — to make sure, in other words, that no species is at risk of extinction. “But it also says that if you’re not able to, you don’t have to. And it’s not clear to me how forest managers are required to prove that they can’t.”

The proposed rule requires forest supervisors to develop plans that “maintain or restore the structure, function, composition, and connectivity of a healthy and resilient ecosystem,” writes Tony Tooke, the agency’s director of ecosystem management coordination, in an e-mail. Yet there’s little in the rule to define those terms.

“How will you or I know that we’ve walked into a resilient ecosystem?” Nelson says. “There’s no clear criteria set out in the draft to determine that.” Nor does it require proof in numbers that such an ecosystem is, as the proposal assumes, beneficial to a variety of wildlife. “I’m afraid the Forest Service thinks monitoring at the species level is burdensome,” Nelson says. “I think of it as a trust-building exercise.” With ecosystem protection as with nuclear arms control, it’s “trust, but verify.”

In short, the new rule leaves a lot up to the discretion of local forest managers. That’s not necessarily bad: Forest supervisors can observe changes at the local level that would elude bureaucrats in D.C. “It’s hard at the regulation level to provide any one-size-fits-all standard,” says Martin Nie, associate professor of natural resource policy at the University of Montana. “I can think of some forest supervisors who’ll go to town with this thing in terms of meaningful standards and requirements.”

Local supervisors under pressure from politics or industry, however, could theoretically veer in a less constructive direction. “The pushback is always economics,” says Congressman Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., who has criticized the proposal for weakening wildlife protection. “But when you have habitat shrinking, species disappearing and wild places not being protected, your decision-making can’t be subjected to biased outside pressure. You have to have strong federal oversight to make sure what you do is based on facts and science.”

Timber and other industry interests have not yet commented on the rule, except to say they’re watching it closely. Meanwhile, the Forest Service will take public comments through May 16.

Francis thinks everyone should consider contributing. For Westerners, “the planning rule affects everything from where you hike to the quality of your drinking water.” After all, it’s your plane the agency is piloting, he says, “and you need to have some way of knowing whether it’s staying on course.”

The funny thing about this to me is that I think I agree with Peter, for opposite reasons. He sees the FS requiring conceptual ideas like resilience as questionable, because he doesn’t know that the concept means what he wants (protecting species). I don’t like requiring concepts in regulations because judges will ultimately decide anything fuzzy based, more than likely, on their own views.

In any conflictual writing exercise (say legislation, writing plans), fuzzy and vague seems good at first because everyone seems to get what they want. It’s when the poor implementers take it forward (and get litigated) we realize that we just postponed, and changed the arena of, the conflict.

Here’s a quote from Martin in the same article:

In short, the new rule leaves a lot up to the discretion of local forest managers. That’s not necessarily bad: Forest supervisors can observe changes at the local level that would elude bureaucrats in D.C. “It’s hard at the regulation level to provide any one-size-fits-all standard,” says Martin Nie, associate professor of natural resource policy at the University of Montana. “I can think of some forest supervisors who’ll go to town with this thing in terms of meaningful standards and requirements.”

But it’s not the supes we really have to worry about.. at least according to Congressman Grijalva..

Local supervisors under pressure from politics or industry, however, could theoretically veer in a less constructive direction. “The pushback is always economics,” says Congressman Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., who has criticized the proposal for weakening wildlife protection. “But when you have habitat shrinking, species disappearing and wild places not being protected, your decision-making can’t be subjected to biased outside pressure. You have to have strong federal oversight to make sure what you do is based on facts and science.”

I guess it’s politicians ;).

The Future of America’s National Forests Depends on Revised Laws and a Restored U.S. Forest Service

Guest post by Les Joslin

Few would dispute the notion that the National Forest System and the U.S. Forest Service are impaled on the horns of a dilemma of dysfunction. On one horn is the lack of a clear-cut role for the national forests. On the other is the lack of an agency staffed by professional forest officers at all levels able to efficiently and effectively manage those lands.

As a consequence, one of our nation’s great treasures, the 193-million-acre National Forest System established by President Theodore Roosevelt and Forester Gifford Pinchot early in the 20th century and managed for its citizen-owners by the Forest Service for the past 105 years, is at risk. At risk with them are the commodity resources—clean water, timber, livestock forage, wildlife habitat—and amenity resources—scenery, outdoor and wilderness recreation, and more—that benefit all. In the West, close to 70 percent of domestic water originates in the forests. Also at risk is the economic survival of hundreds of rural communities that depend on the forests for jobs created by renewable resources and by recreation.

The role of the National Forest System, of course, is a matter of law. Indeed, of laws—too many and often conflicting laws. Evolution of a clear-cut role for the national forests is as critical as it would be complicated. It would depend on a successful legislative review and revision of these myriad laws to produce a more workable definition and implementation of that role. This is a challenge to the political will of our nation.

Successful meeting of this challenge would produce a revised and realistic legal framework for the National Forest System and for the smaller and more efficient and effective Forest Service necessitated by the get-real-about-deficit-reduction future faced by the U.S. Government and the American people as the United States careens toward national bankruptcy. This would support a revised forest planning rule that would prioritize and implement the community relations and resource management field work that needs to be done and would not be driven by selfish interests and peripheral considerations.

Whatever the role of the National Forest System, a truly viable U.S. Forest Service would have a well-defined national forest management mission implemented by leaders who lead effectively and followers learning to lead effectively—a professional corps of line and staff officers with field savvy and agency panache who understand and practice the art and science of, as the Forest Service’s own motto puts it, “caring for the land and serving people.”

This would be a corps of capable and competent “forest rangers” present and visible in the forests rather than hidden away in offices; supported by rather than subservient to technologies; doing jobs rather than outsourcing them. This would be a corps that capitalizes on rather than squanders its proud heritage, and attracts rather than alienates those who would serve in it rather than just work for it. This would be a corps worthy of the admiration and respect and support of the National Forest System citizen-owners who should be served and would be served by it.

The functional Forest Service of yore grew its own corps of forest officers—dedicated professionals and technicians—on mostly rural or remote ranger districts on which the district ranger depended on each and every member of his small crew to ride for the brand and pull his or her own weight to “get it done” together. But most such ranger districts have been lost to consolidation and urbanization and cultural change. And the generalists they grew have been replaced by more narrowly-focused specialists.

Developing such a corps is the essential challenge for the Forest Service leadership and its U.S. Department of Agriculture masters.

Without such ranger districts offering the formative experiences and training they once did, the Forest Service should train qualified men and women selected to serve as forest officers at a national, residential U.S. Forest Service Academy situated on a national forest that could accommodate and provide and materially benefit from—much as teaching hospitals do with medical students—a wide range of rigorous academic and field experiences. This academy would comprise an entry-level officer candidate school and a mid-career advanced course. And, during its earlier years, it would conduct a short update course for current district rangers.

At the officer candidate school, those recruited to be the line and staff professionals and leaders of the Forest Service would learn to be forest officers first and specialists in one or more relevant disciplines—in which they already would have academic degrees or significant experience—second.

The challenging course would inspire the will, inform the intellect, and develop the physical and practical and philosophical wherewithal of a corps of professional and technical members—not employees, but members—who would be the able and willing and dedicated forest officers required by the Forest Service. After significant career assignments and experiences, these forest officers could return to the academy for mid-career training to further their preparation for district ranger and senior line as well as staff assignments. The academy would be an intellectual and cultural wellspring of the Forest Service, an institutional home of the resolve and resourcefulness the Forest Service needs to succeed at any well-defined mission revised laws would prescribe.

Now is the time to act. It’s too late for a business-as-usual, study-it-again-sometime, put-it-off-until-somebody-else-is-President-or-Secretary-or-Chief approach. The national treasure that is the National Forest System is at risk now, the Forest Service is in extremis now, and the time for action—real action leading to early results to save both the System and the Service for the citizen-owners of the former and the good people of the latter—is now!

Audacious? Yes! Expensive? Yes! But certainly not too expensive for a U.S. Government that allocates hundreds of billions of dollars to rescue Wall Street and spends over two billion dollars (in 1997 dollars) per copy for B-2 Spirit stealth bombers. Indeed, the entire proposed U.S. Forest Service overhaul process could be funded and the entire proposed U.S. Forest Service Academy could be established and operated for a decade or two for half the cost of just one of those bombers.

Expensive? Yes, except when one considers that the value of the national forests to their citizen-owners is in the trillions of dollars, and that these lands are the source of life-supporting water for millions of people and myriad other values for millions more.

Expensive? Yes, except when compared with the millions of dollars spent on wildfires and the billions of dollars in damages to the land and citizens resulting from these holocausts.

Expensive? Yes, except when compared with the opportunity costs of the bureaucratic equivalent of fiddling while Rome burns.

Isn’t a truly effective investment in the future administration of the National Forest System and all the benefits derived by its citizen-owners in terms of commodity and amenity resources as well as jobs and more stable communities worth at least that much?

Impossible? Only if we tell ourselves it is, roll over, and give up.

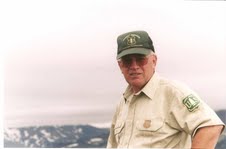

Les Joslin is a retired U.S. Navy commander and former U.S. Forest Service firefighter, wilderness ranger, and staff officer. He teaches wilderness management for Oregon State University, writes Forest Service history, and edits the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Association’s quarterly OldSmokeys Newsletter. He lives in Bend, Oregon.