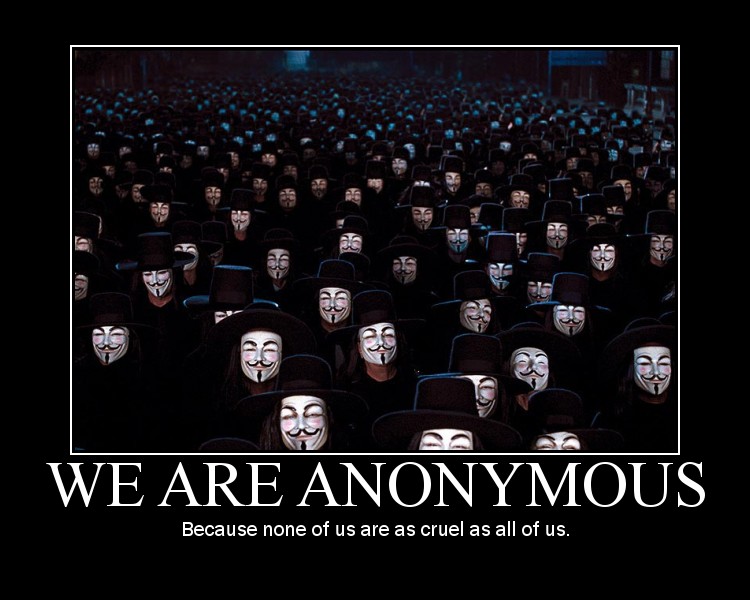

As we are seeing these days in the Middle East and Africa, even Wisconsin, democracy is never easy—whether to initiate or to keep. What we know is that we cannot maintain a democratic form of government without “voice.” After all, democracies are “temples of talk.” Yet, many times it proves too threatening to express opinions, or even to interject facts, into public discussions. Discussions sometimes threaten work, family, or community relations, yet without discussions, none of these institutions can long survive. In many situations, only the few dare voice opposition to either the status quo or to proposed change. But these days it is getting easier to be heard without some of the threat that has traditionally attached to voice. We are seeing an upwelling of “anonymity” as a form of voice.

I follow a bunch of blogs in the economics and finance arena. Believe me, there are a bunch of these. As you might guess, given recent financial shenanigans events, there are very active conversations in these blogs, and also in mainstream periodicals—that themselves now embed blogs. Some who comment and some who blog remain anonymous. Why? Because of perceived threats, sometimes very real threats. Anonymity allows a particular voice that would be disallowed if people were to “post” or comment under their real names.

Here are two examples. One noted financial blogger, The Epicurean Dealmaker, posts as TED (an acronym). TED is widely viewed as a sage in the arena of Wall Street financial deal-making. TED claims to be a mid- to higher-level employee of a Wall Street firm. He (or she? Not likely!) has been very critical of the culture wherein he makes a fine living. And his posts, and guarded/shielded interviews, have helped to unravel some of the mysteries of this arcane world. TED is unabashed. He even challenges people to find out who he is. He is so sure of himself that he believes that he will not be “outed.”

Then there is Maxine Udall (girl economist), who spent a few years blogging and attracted a following. Turns out that “Maxine” was not her real name. Unfortunately, the real author passed away suddenly a few weeks ago. She was “outed” after her untimely passing. Most everybody had previously thought Maxine was a savvy graduate student. Turns out that she was a professor. Had she been blogging under her real name, her voice would have been less edgy.

If you want to comment with anonymity, here’s what you can do. First create a fictitious name/email address, then begin commenting. Or, particularly if you want to carry conversation “off line” set up a real email, like TED did, with a “handle”, not your real name. If you feel you have more to say, start an anonymous blog—it is very easy.

We need more “voice” in the public lands arena. I don’t understand why there are not more blogs on matters we discuss here. Is it just timidity? Is it that there is so little passion among employees and public lands watchers? Really? Likely not. So what else is going on?