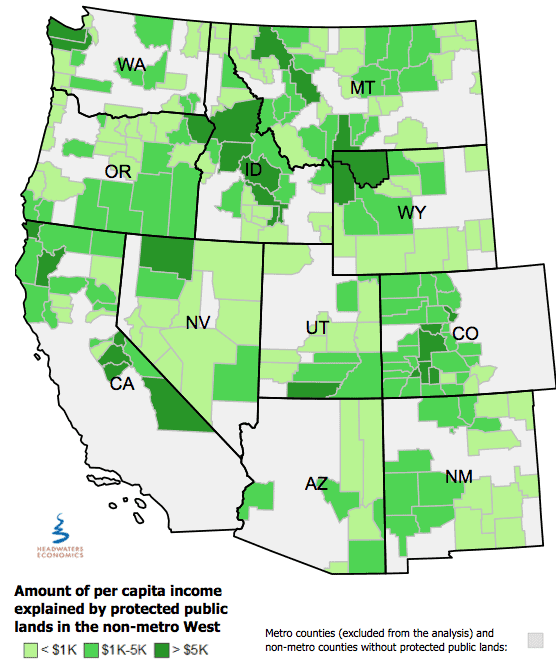

Headwaters Economics – a non-profit economic research group based in Bozeman, Montana that specializes in community and economic development – has created an interactive map to show the amount of per capita income explained by protected federal lands for each county in the non-metropolitan western U.S.

Headwaters Economics – a non-profit economic research group based in Bozeman, Montana that specializes in community and economic development – has created an interactive map to show the amount of per capita income explained by protected federal lands for each county in the non-metropolitan western U.S.

For example, in Gallatin County, Montana $2,655 of the per capita income (7% of total PCI) can be explained by the presence of protected public lands. Or, in Gunnison County, Colorado, $5,203 of the per capita income (15% of total PCI) can be explained by the presence of protected public lands. Meanwhile, in Teton County, Wyoming $23,897 of the per capita income (24% of total PCI) can be explained by the presence of protected public lands.

The new interactive map and explanation take into account each county’s characteristics and shows an estimated amount of per capita income that can explained by protected federal lands for each non-metropolitan county.

This new county-specific analysis builds on earlier work (West Is Best) by Headwaters Economics that looked at the U.S. West’s 286 non-metro counties as a region, and found a meaningful relationship between the amount of protected public land and higher per capita income levels in 2010. According to this analysis, the effect protected public lands have on per capita income can be most easily described in this way: on average, western non-metro counties have a per capita income that is $436 higher for every 10,000 acres of protected public lands within their boundaries.

Matthew, just to be clear, correlations in a complex system like the economy are not always associated with causation.

Below is one of the points I raised when we discussed it before: that it’s not clear that “protected lands” has any real meaning. Here’s a link to my previous comment on the Headwaters Report. Does anyone really think that if we removed the ski areas along I70 and made those areas a national monument, that the economy of the I70 corridor would improve? Or maybe the economy of Colorado?

Then climate change might be a good thing for the economy, because those ski areas would ultimately close and we could convert them to parks or wilderness, and Colorado would be better off?

Here’s a link to my previous comments on the “West is Best” study.

Every piece of public land has some kind of “protection”. So, that would make the definition fluid enough to make it fit any desired study outcome. It’s a HUGE reach to claim such outcomes when so very many variables are ignored.

In addition, state, county and private lands have “protections” of various kinds and are also more or less, “park-y”. For example, I use Jefferson County open space more than nearby state and national parks because a) they are free and b) they are close, reducing my carbon footprint. In fact, the one I use most, I can walk to.. perhaps those are the most utilized by folks, and most important in quality of life for actual residents of these communities.

Per capita income rank:

1. Washington, DC

2. Connecticut

3. New Jersey

4. Maryland

5. Massachusetts

6. Virginia

Full table here.

It doesn’t take statistical masturbation to conclude that % federal land, regardless of its “protected” status, and per capita income are not correlated at the state level. With the Headwaters study attributing differences in per capita income on the order of 1% to protected land status, I’m underwhelmed.

Also a stark contrast between the Headwaters’ thesis (protected federal land increases economic wealth) and EcoNorthwest’s “second paycheck” argument, e.g., “if amenities in a region improve people will tend to move to that region, bidding houses prices up and wages down.”

Andy, thanks for your link…

I also looked at this list of highest income counties by median household income http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_highest-income_counties_in_the_United_States

Looking at 2011, of the highest income counties, there appear to be 3 in the interior west, Douglas and Boulder Counties, Colorado, and Davis County, Utah. which are fairly urban (Metro-Elk).

Interestingly, one interior west county, Los Alamos was #4 in 2006-2010, and did not place in the top 100 in 2011. I wonder what happened?

I conclude from Andy’s links that there are many different economic statistics related to income, at many scales, that form a variety of different patterns.

Am I to conclude from this study that if all of the land in a county were “protected” (whatever that means) then local economies would soar? Tell that to Liberty County, Florida or Lane, Douglas, Curry etc. counties in Oregon where federal land management for the “protection” for the redcockaded woodpecker, marbled murrelet or spotted owl has produced near bankruptcy. Get real!

And I’ll bet that 80% of Gallatin county wants the Bozeman Municipal Watershed project to be logged just like the majority of “Aspenites” want Smuggler mountain to be logged (Ican’t think of project name right off). Yes, even Aspen has embraced forestry as the hip new thing. For most people it’s not an “either or” thing. It’s a “there’s enough to have both thing.”