Many believe that passing international agreements will be the way to slow or stop climate change. As for me, I believe in the power of human creativity, technology,economics and good will.

If I read the many stories in the press, even “science” stories, it seems like there are more projections of how bad things will get. And if there are stories from observations that things aren’t going as badly as thought, things are still bad because the pressure will be reduced for governments to sign on to international agreements, requiring many regulators and negotiators and checkers. All friction in the system (so to speak ;)), of directly producing and distributing low-carbon energy. Not to speak of the industry of calculating and projecting things that can’t be known. And I wonder if just hearing this side of things might cause people to despair. Which I can never believe is a good thing.

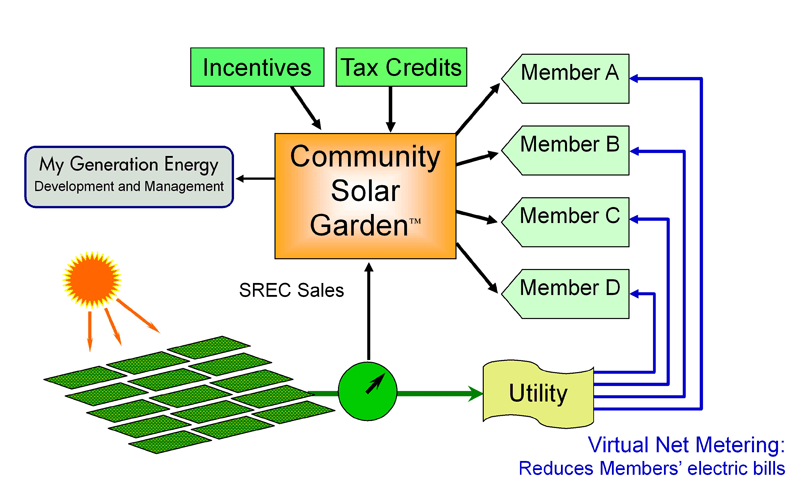

So here’s a piece in the Denver post on solar gardens:

Only about a quarter of the nation’s rooftops are big enough and sunny enough for rooftop solar, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden and not everyone can afford a rooftop array that can cost $12,000 to $18,000 in Colorado.

Solar gardens enable people who don’t have a sunny roof or the money to buy a full array to buy or lease a piece of an array — in some cases for as little as $1,000.

The Colorado Community Solar Garden Act was passed in 2010 to promote the community solar installations and directed the state Public Utilities Commission to include gardens in renewable energy plans. Xcel’s new incentive program for 18 megawatts of gardens in the next two years came out of that effort.

Xcel opened it program on August 15th and within 30 minutes had three times as many applications as it could fill.

Operators will get paid on a sliding scale — 14 cents to 10 cents — for each kilowatt-hour the garden produces. Residents will get a credit on their bill of about 6.8 cents a kilowatt-hour.

The Carbondale-based Clean Energy Collective, a private developer specializing in solar gardens, will develop six projects.

Among them are two gardens in Denver, where space is at a premium. One 400-kiolwatt array will cover the curved roof of the Lowry Hangar 2 and another 500-kilowatt installation will form a parking lot awning at the Evie Dennis school campus.

At the Golden Hoof Sustainable Demonstration Farm, in East Boulder, the collective will build a 500-kilowatt solar garden on pillars over a farm field.

“We’ve looked for innovative solutions for each community,” said Paul Spencer, chief executive officer of Clean Energy Collective.

The collective’s other solar gardens include one 108-kilowatt project in Arvada and two 500-kilowatt units in Breckenridge.

Solar Panel Hosting, Namaste Solar and Solar Power Financial teamed-up to win 497-kilowatt projects in Aurora and Saugache County.

“Installation will be similar to any other array,” Namaste’s Jones said. “The more complex aspect will be dealing with subscribers.”

Community Energy Solar, a Boulder-based project developer, and Bella Energy, another Boulder-based commercial solar installer are developing two 500-kilowatt projects in the City of Lafayette.

The projects will be on municipal land, one is adjacent to Lafayette’s water treatment plant and the city will be the prime customer for the garden, said Community Energy’s Eric Blank.

Lafayette officials and Community Energy executives are planning to donate output to low-income families, who would become subscribers to the garden for free.

“These ten projects are in areas that serve a million people, so the gardens will only be able to take a fraction of a percent of the potential customers,” said the Clean Energy Collective’s Spencer.

Here is an interesting article about new grids “Electric Avenue, When People Have the Power”..it’s subscription only at New Scientist but libraries usually carry it.

What’s the alternative? For the individual, complete separation from the grid remains an expensive, unreliable option suited only to the very rich or to determined eco-warriors.

But a small group of energy researchers is arguing for a third possibility, which they say is emerging thanks to advances in sensing, local storage and small systems for tapping renewable energy such as rooftop solar panels and micro wind turbines. At its heart is a vision of “community grids” that rely mostly on local energy sources and storage. They buy energy from the larger national grid when necessary, but can also feed renewable energy into the national pot. Such a system, they argue, could reduce demand on the main grid, freeing it up to run on a higher percentage of renewable energy sources.

It started with small grids that have for decades successfully allowed a range of self-contained communities to generate their own electricity. These range from military bases, university campuses and jails to remote villages in Alaska, for example, that have found it too expensive to connect to the central grid.

Most of these derive their electricity largely from constantly available sources like diesel generators and batteries. Not all, however: a microgrid at the University of California in San Diego adds clean sources like wind and sun to the mix.

Such microgrids could graduate from speciality niches and become much more common. To do that, however, it would be necessary to find a way for individuals to store the electricity in the community. One source with great potential, says Willett Kempton of the University of Delaware in Newark, is the batteries of electric cars. In April, Kempton, working with the local grid operator and a utility company, unveiled a system to enable electric cars to supply energy to the grid as well as taking it. Car owners can then earn around $5 per day by selling energy, along with providing the grid with a back-up supply.

In many ways, electric car batteries are the perfect storage medium for renewable energy. “The average US car is driven only 1 hour per day, the batteries are huge, and the times of use are fairly predictable,” says Kempton.

When plugged in, the circuit queries the grid every 4 seconds and receives a signal telling it to either charge, discharge or do neither, depending on what the grid needs.Kempton recently compared this Grid Integrated Vehicle (GIV) system with warehouses full of batteries and hydrogen fuel cells. “All three work, but GIV is the least expensive way to do it,” he says.

When I am a philanthropist (that is my next career goal), I would fund studies around which interventions could make the greatest difference in moving us from where we are in terms of energy to where we need to be. I would not focus on programs of “no to biomass” but rather focusing on these positive interventions, and finding an end state that most of us would support and moving there. No “enemizing” allowed.