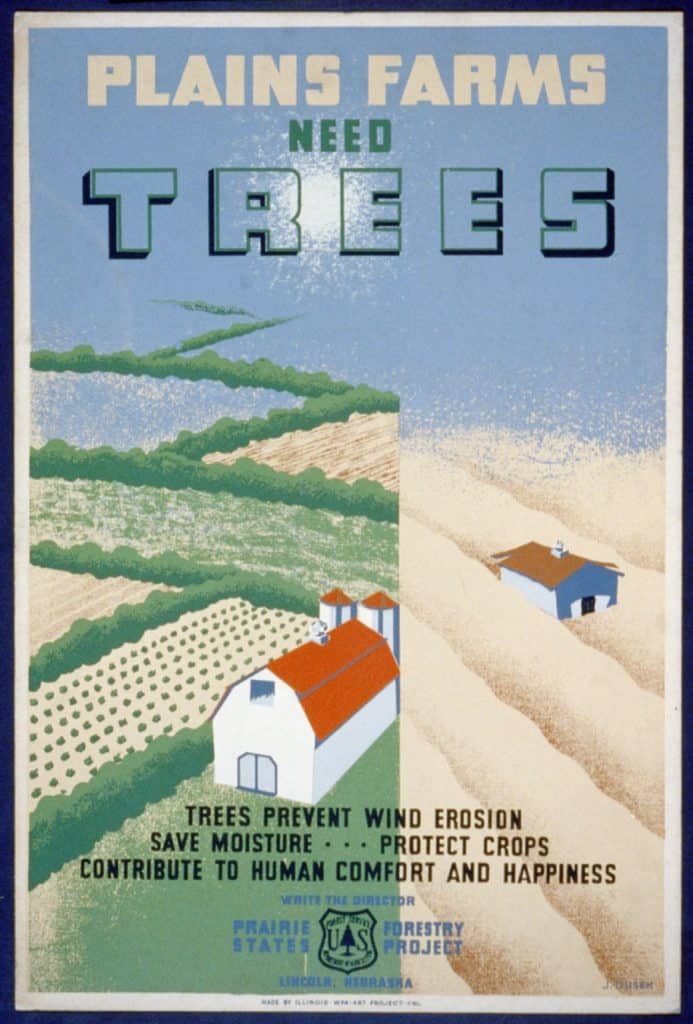

between 1936–1940 (Work Projects Administration

Poster Collection, Library of Congress).

Here’s an excellent piece of history by by Andy Mason and Sarah Karle from the Rendezvous (Rocky Mountain FS retiree newsletter). I particularly liked these photos that show how a few folks with a big dream for improving the environment, almost a hundred years ago, succeeded (after hard work, research and experimentation) succeeded, and is still working today.

Prairie States Forestry Project (1934-1942)

In 1934 President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the New Deal’s Prairie States Forestry Project to create “shelterbelts” of newly planted trees to mitigate the effects of the Dust Bowl in America’s Great Plains. The project stretched from North Dakota to northern Texas and helped stabilize soil and rejuvenate farm communities affected by the dust storms. Under Roosevelt’s Administration from 1934 to 1942, the program both saved the soil and relieved chronic unemployment in the region. The U.S. Forest Service was responsible for organizing the “Shelterbelt Project,” later known as the “Prairie States Forestry Project.” Paul H. Roberts from the agency’s Research Branch directed the project that was headquartered in Lincoln, Nebraska.

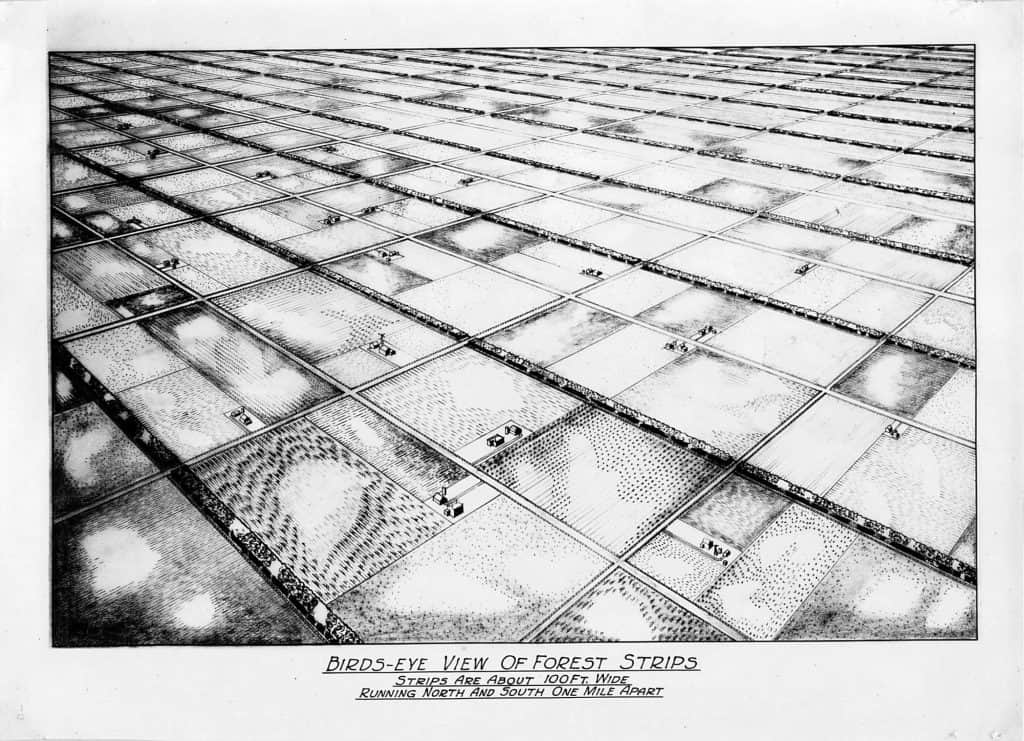

When FDR came to office in 1933, the Great Plains and other regions were suffering from what would become an almost decade-long period of economic, environmental, and social crises. Several large-scale factors led to the environmental devastation of the Dust Bowl and contributed to the economic hardships of the Great Depression, leading to the social upheavals that followed. As president, FDR used conservation projects as a job-creation tool against the Great Depression, and within months of becoming president, he devised the Prairie States Forestry Project. The project, based to some degree on Roosevelt’s personal experience with forest management, was proposed as an ambitious “Great Wall of Trees” using shelterbelts across the Great Plains to reduce soil wind erosion, retain moisture, and improve farming conditions. Trees were typically planted in long strips at 1-mile intervals within a belt 100 miles thick. At the time, it was believed that shelterbelts at this spacing could intercept the prevailing winds and reduce soil and crop damage. The project used many different tree species of varying heights, including oaks and even black walnut. The plan engaged scientific knowledge with shifting political ideals, including regionalism and the role of government in the conservation of private land.

Though seemingly beneficial, the Forestry Project was ridiculed from its inception. Some professional foresters expressed doubts about its chances of success, while the general public perceived it as an outdated scheme of dubious credibility to “make rain.” Despite a general lack of scientific and Congressional support, the Forest Service worked across six states with local farmers, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Works Progress Administration to plant over 220 million trees, creating more than 18,000 miles of windbreaks on 33,000 Plains farms. Although Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps workers planted the trees and shrubs, landowners were responsible for their long-term care and maintenance. At the height of the Great Depression, the project employed thousands of residents (notably both men and women) of the Plains states and CCC members from around the country.

The program officially ended in 1942, but by 1944 (scarcely a decade after its inception} environmental and economic benefits from these shelterbelts, including land management practices, control of wind erosion, soil conservation, cover for game birds, and the creation of snow traps along highways, were already apparent. Since 1942, tree planting to reduce soil losses and crop damage has been carried out primarily by local soil conservation districts in cooperation with the Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service) with help in later years from State forestry agencies aided by U.S. Forest Service programs. Today the rows of shelterbelt plantings, while diminished by subsequent changes in agricultural policies and practices, continue to communicate culturally recognized signs of human intervention and interaction with the landscape.

and that’s how the Barred Owl got to the PNW. Awesome.

Historically the Great Plains had much more forest cover than is commonly believed. For example, Iowa was 22% forest, mostly in riparian belts. It took 100 years and a lot of effort to remove those forests. I doubt planting shelterbelts had much to do with Barred Owl incursions in the PNW. More than likely it was poor forest management in the PNW that allows Barred Owls to out-compete owls indigenous to those forests.

Planting shelterbelts was one of the more useful programs to come out of that era. These small patches of forest continue to add a modicum of ecologic diversity and biologic activity to a devastated landscape.

Mark and Scott, as a biologist I think that certain species have advantages and disadvantages such that when conditions change, they may grow or decrease in populations. Conditions change for a variety of reasons (climate, other aspects of the environment, competitor, parasite and predator adaptations, and all the permutations thereof). So it seems like the Barred Owl is a bad guy.. is that a biological thing or a philosophical thing or ???

Thanks for solving a mystery. I wondered how those trees got there. Game bird hunters must love them. I am still curious about the Osage Orange. How did it get where it is now?

I checked on Wikipedia and it had many interesting things to say about this tree, including that it was used in shelterbelts… and Native Americans used it to combat cancer, and the EPA doesn’t think it’s effective as an anti-insectant. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maclura_pomifera

It would be interesting to see more about the impact of shelter belts and even natural tree growth around ponds are being removed from the midwest to expand farmland. I’m wondering if there is a way to increase public awareness or their importance? Is there any further research on this as it relates to maintaining productive and healthy farmland?