Yes, what if. The full article from today’s Missoulian is here, and some interesting snips are below.

“It’s a counter-intuitive result,” said research ecologist Sean Peck. “We put out the fire, but in the long run, there are negative unintended consequences. If we’re putting out all fires under moderate weather conditions, the fire we can’t put out will burn under extreme conditions.”

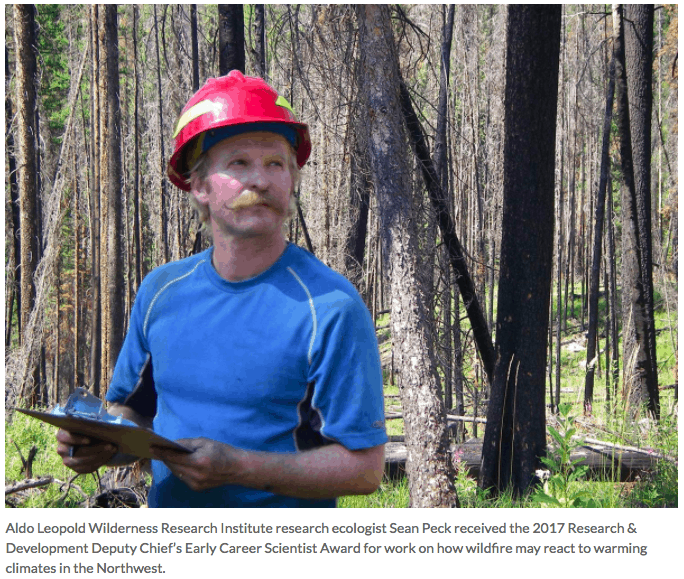

Peck’s work at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute on the University of Montana campus recently earned him the 2017 Research & Development Deputy Chief’s Early Career Scientist Award. Since earning his doctorate from UM in 2014, he’s been lead author of nine peer-reviewed journal articles and co-authored another 11.

Much of Peck’s work focuses on wildfire in federal wilderness, including the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex and the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. Forest fires there typically burn without the swarms of yellow-shirted firefighters and red-tailed aircraft trying to suppress them….

“I think outside wilderness areas, we’re selecting for high-severity fire,” Peck said. “It’s like selecting for a gene in corn crops. It’s not done on purpose, but it happens with certain management practices. We’re not allowing fires to burn in non-extreme years. So fires only occur during extreme events. Those fires are the ones we could not put out.”…

Peck’s current work looks at how future climate changes may affect the tempo of fire seasons. He’s testing the idea that we’re likely to see more extreme fire events in the short term, but less severe fires several decades from now as the climate warms.

“We think we may see the spruce-fir forests converted to something else that may be more resistant to fire, like Douglas fir and ponderosa pine,” Peck said. “And at some lower elevations, dry-forest types are projected to convert to non-forest vegetation, grassland or shrub land. Dry forests are barely hanging on now.

“As Montanans, we’ve grown up with certain kinds of forests,” Peck added. “They are going to change. We can accept it, but it will happen whether we want it to or not.”

Of course, it is all site-specific, especially-so in Montana.

“What if our efforts to stop wildfires actually make them bigger?”

Or what if directly addressing the primary causation — Anthropogenic Climate Disruption– is the last thing the corporate state wants? After all, if the only tools in the agency/industry toolboxes are chainsaws and outsourcing to the corporate firefighting industry, why address the cause if you’re making fantastic money fighting the symptoms?

This steady state of affairs of course being maintained through carefully managed media narratives, while burning through taxpayer dollars faster than you can ask Smokey, “Whatcha been smokin’ there?”

If the fires are not threatening life and property, then sure, why not manage them instead of suppressing themm Putting aside the issue of whether human should be residing in forested land (thus elevating the human concern for “life and property”), where is the harm in allowing an ecological disturbance process play out? (I recognize this potentially overlaps another thread that has put “ecological” under scrutiny)

Tens of million of people, including seniors and children, live ‘downwind’ from burning National Forests. Hey, we’ve even seen one group come here insisting that prescribed burns be banned, and that fires be aggressively fought, in every situation. There needs to be a compromise but, everyone wants it their way.

And has that dynamic (” I want it my way”) been with us in this country for generations, or is it more of a recent occurrence? Say, since the late 1800s/early 1900s? I can see myself cooperating with a “greater good” approach if others around me see the same “greater good”. But, if none of us see any “greater good”, how do we move constructively forward? I argue the “every person for themselves” approach is not helping, and maybe not even working. What has to fail before we all decide to work together to create a better situation for all if us? And isn’t that answer also the answer to solved the “tragedy of the commons”?

People are “managing” not “suppressing” fires outside wilderness, right now, or there wouldn’t be debates about those tactics and the results, as we have seen on this blog.

This is one of those classic “straw person” formerly known as “straw man” arguments, in which someone will say “those folks shouldn’t be doing that” but in reality, those folks aren’t actually doing that.

Hey [Hay?], not much straw person here, in my opinion. At least not 98% of the time, according to the U.S. Forest Service in June 2017.

“Tidwell said President Donald Trump’s fiscal 2018 budget will provide the resources ‘that are necessary for us to maintain our success rate of suppressing 98 percent of our fires during the initial attack.‘” Source, Arizona PBS

Having read the source link you provided, Matt, and given the “98 percent of our fires” are being successfully suppressed, I can surmise where the missing 2% of suppression (though not of fire) occurs. It is most likely to be found from the source himself: USFS Chief Tom Tidwell being reminded by Senator Jon Tester to not be shy, Tidwell needs to ” speak truth to power, but you need to tell us, ‘This isn’t working.” Unsuccessful Suppression indeed.

My hunch on that other 2% is based upon the second definition found for straw man:

(2. “a person regarded as having no substance or integrity: a photogenic straw man gets inserted into office and advisers dictate policy.”

(So I have to agree with Sharon’s invocation of “straw man.” But not the context she quite unsuccessfully attempted. )

On the other hand, the sole comment to the linked article coincidentally references precisely the dynamic I referenced in my earlier comment on this post, when I asked, “After all, if the only tools in the agency/industry toolboxes are chainsaws and outsourcing to the corporate firefighting industry, why address the cause if you’re making fantastic money fighting the symptoms?”

Here’s an excerpt of that comment by Jack Sexton in the linked news article:

“Retardant is a sole source contract. The USFS only allows retardant in air tankers. A company hired senior retired USFS senior employees. The company patented a retardant. Four months after the patent was approved, the USFS changed the specification for retardant. The new specification matched the patent.

The result was a 300% increase in the cost of retardant, the retardant is no more effective than the retardants it replaced and the retardant kills fish with the same ease the retardants it replaced did.”

(As Sharon might quip, … “Just sayin'”)

That 98% likely refers to the percentage of fires for which a suppression strategy is identified during IA. I seems less likely to me that they would consider a fire identified for management purposes as “unsuccessful” initial attack.

Nope, that’s likely not what the 98% refers to.

The 98% refers to the U.S. Forest Service’s “success rate of suppressing 98 percent of our fires during the initial attack.”

“The Forest Service and its partners suppress more than 98 percent of wildfires on initial attack, keeping unwanted fires small and costs down. However, the few fires that cannot be suppressed during the initial stages run the risk of becoming much larger.” SOURCE: USDA

To be precise, the FS defines “initial attack success rate” as the % of ignitions that are less than 300 acres when declared out. Most ignitions (about 70%) would never grow beyond 300 acres even if no one did anything to suppress them.

Thanks for chiming in with that tidbit of information, and perspective. It’s a never-ending battle to ensure accurate information is on this blog.

“Most ignitions (about 70%) would never grow beyond 300 acres even if no one did anything to suppress them.”….. Is there a link to this conclusion?

Soooo, it looks like this is just Andy’s opinion.

Matthew

Consider: “Tidwell said President Donald Trump’s fiscal 2018 budget will provide the resources “that are necessary for us to maintain our success rate of suppressing 98 percent of our fires during the initial attack.””

“98 percent of our fires” is meaningless since it tells us nothing about the associated percentage of acreage burned.

Reading further down in your link you will see “It’s really now 1 percent of fires that contribute often to 20 or 30 percent of our costs“. Which gives you an indication of the difference between % of fires and % of acres burned. This is because cost is a better proxy for proportion of acres burned than than the % of the number of fires.

By my rough calculations given below (1), that 98% suppressed fires number being thrown around probably accounts for only 58% of the acreage burned leaving roughly 42% of the acreage burned resulting from the 2% of the fires that were not suppressed.

As you yourself state in a comment above “It’s a never-ending battle to ensure accurate information is on this blog.” But accurate information is useless if you don’t understand how to use it properly for decision making.

(1) Crude calculations referred to above:

–> Given that as of 12/8/17: There have been 58,109 fires and 9,284,895 acres burned so far this year as compared to the average for the last 10 years of 64,204 fires and 6,083,264 acres.

** We quickly see that the average acres burned per fire is 160 for 2017 ytd and 95 for the average of the last 10 years so 2017 ytd has had larger fires than the 10 year average.

–> Given Andy’s 300 acre max for a fire to be considered to be suppressed.

–> Given Tidwell’s 98% of fires are suppressed.

* We would estimate that 56,947 fires have been suppressed ytd (0.98 X 58,109)

–> Ruled out –> Assuming the worst case scenario that all suppressed fires burned 300 acres

–> Ruled out –> We find that 300 acres per suppressed fire would give us 17,084,046 acres burned so we have to come at this from a different angle to get a more accurate acreage for suppressed fires since the total ytd acres burned is only 9,284,895.

–> assuming the 10 year average of 95 acres for all fires as the max acres for suppressed fires in 2017 ytd, we’d get 5,409,948 acres burned by suppressed fires (0.98 suppressed X 58,109 total # fires X 95 acres per suppressed fire). This 5,409,948 acres number is probably too high for avg acres per suppressed fire since it was the avg for all fires over the last 10 yrs.

** That would mean that we have a conservative estimate of 42% (1 – (5,409,948 / 9,284,895)) for the acreage burned ytd in 2017 which was not suppressed and occurred on the 2% of the fires not suppressed which compares reasonably well in terms of order of magnitude with Tidwell’s statement that ““It’s really now 1 percent of fires that contribute often to 20 or 30 percent of our costs” subtracting 25% ((20+30)/2) from 42% would mean that 17% came from the other half of the 2% (the 1st 1% of fires being 25% of acres).

** Sorry but I couldn’t get ytd numbers for 2017 suppressed fires and their acres so I’ve resorted to ballpark guesstimates to roughly show the magnitude of the discrepancy as being 40% (2% for # of non-suppressed fires versus 42% for non-suppressed acres (i.e. 2% of the fires probably constituted roughly 42% of the total acreage burned)).

Gil,

There are two contemporary items regarding your well-intentioned response here that cause serious concern for me and both invoke the predicament of cognitive bias — something we are all set-up to suffer here on this blog but rarely acknowledge.

The first is from the editorial staff of today’s New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/09/opinion/sunday/looting-americas-public-lands.html

I invoke this, not for what it contains (which describes the formula for, and political predicament of political/corporate capture of our public lands), but for what the editorial does NOT contain: the consequences of willful ignorance of the forces unleashed by, not merely Business as Usual on steroids, but by the most Unusual of Business as Usual: the singular pursuit of self-immolation in the conduct of business as usual.

The second is from scientists whom will never find such an international soapbox as a NYT oped.

They resorted to speaking their conscience and their findings from their blog of December 4th of this year, entitled, “Ridiculously resilient ridge” http://weatherwest.com/archives/tag/ridiculously-resilient-ridge

The blog entry explains the consequences of Business as Usual: the catastrophics of climate disruption linked to GHG emissions and Sea Surface Temperatures in all likelihood at the center of extended drought of the American West resulting in the catastrophic wildfires we argue about on NCFP.

Why then, are we are reduced to polemics here agonizing over the minutiae of management of the effects of a problem — the causations of which will be reliably persistent and result in reliably nonlinear increasing of consequences in the near and long terms?

This leads me to asking you, why would you commit such good intentions to addressing the effects of a problem, that is clearly offered in the best of intentions, but which play no part in seeking the solution to causality?

Even NEPA must acknowledge these “irreversible and irretrievable consequences” resulting from federal actions — how are we as a species, to survive them if we fail to address the well-known causation of wildfires?

(I ask you instead of Sharon because her position is unavoidably clear — she is an unabashed and self-admitted outlier of the international consensus of the scientific community on these matters.)

OH NO! How are we to survive thinning projects which do not cut any large trees?!?!?! We’re gonna DIE! *smirk*

David

Re your 1st two paragraphs and your statement as to the need to correct/combat: “the consequences of willful ignorance of the forces unleashed by, not merely Business as Usual on steroids, but by the most Unusual of Business as Usual”

–> Unfortunately, sin doesn’t confine itself just to business, I find the same problem in envro leaders who refuse to consider the consequences of their positions that fit in with their wishful thinking instead of established science. I find the problem to be increasingly prevalent in all organizations the further up the ladder you go whether it is politics, religion, business, lawyers, “environmental” organizations or whatever. A former head of the Sierra Club got them started on the across the board anti clearcut path regardless of species, site conditions and landscape level balance. His basis was that at six or eight years of age while flying with his parents he saw some clearcuts and was repulsed by the aesthetics that he saw without having any knowledge as to the science involved and the fact that the trees would grow back. One size fits all is great as long as you don’t know what you are talking about.

Re your paragraphs 3 through 5: I didn’t find any concrete conclusions in reading your second article. I read of some research and modeling that led the authors to some suppositions which even they conceded were possible linkages which may or may not be the causal effect that you read into their paper that they specifically stated was not appropriate.

As to your final four paragraphs:

re your question: “Why then, are we are reduced to polemics here agonizing over the minutiae of management of the effects of a problem”

–> Because everyone accepted the 98% number as meaningful in the context of this post and speculated on the reason for the other 2% instead of applying critical thinking skills to understand the literal meaning of what was quoted.

–> Because no one has shown how we can change the weather to eliminate the initiation of the 2% of the fires that result in ~ 40% of the lost acreage.

–> Because forest/fire science validated by extensive operational experience tells us that we can (over a long period of time) incrementally reduce the effects and therefore the acreage, health and infrastructure loss from the 2% of fires causing the ~ 40% acreage loss. Is the health of those downwind so unimportant that we don’t even want to try?

–> Because science doesn’t always translate to law and the enforcement thereof. Some of us thought that chlorofluorocarbons were outlawed and the holes in the ozone were getting smaller but now we find out that it was sort of a voluntary thing and though the voluntary actions were helping, we are just now getting around to making it a law.

–> Because, as a forester, I can only deal with what I know will improve or deteriorate the situation.

–> Because those who are supposedly the climate science “experts” haven’t come up with specific implementable solutions that everyone can understand and therefore can convince people to vote for. They can’t even convince the opposition with science so they have even considered using the law to silence the opposition just like a certain church did to try to silence Galileo.

–> Finally, because just like a burn on your body, you:

1) treat the effects of the burn that you have rather than lay there and say “”Why then, are we are reduced to polemics here agonizing over the minutiae of management of the effects of a problem””, we should just lay here and accept what happened and accept that we can’t do anything to minimize its impact in the future. That seems to be your position.

2) analyze the cause and effect and rearrange the environment, to the extent that resources allow, so as to (incrementally over time) minimize the risk, extent and degree of a future burn. The “minutiae” is where the rubber meets the road and involves managing the forest and the WUI in a prioritized manner so as to reduce the carrying ability of a fire initiation in high access areas and reduce the amount of WUI and the carrying capacity of fire within the WUI. My position, is that you use the knowledge that you have and reduce the risk that you can immediately and keep nibbling away at the problem over time as your knowledge increases.