I happened to run across the Chokecherry-Sierra Madre Wind Project while driving around the Medicine-Bow National Forest and noted a road that seemed completely out of character for the area (i.e., paved). So I wondered why and discovered the Chokecherry-Sierra Madre Wind Project and the associated Transwest transmission line project. I hadn’t seen much about it in the press; I guess getting the 300th of 900 state/federal/county permits is not too exciting for anyone outside of Carbon County. And there isn’t much controversy, and if there were it wouldn’t be along the traditional narrative lines. After all, it is corporate, industrializing the landscape, has wildlife impacts and so on.

From the BLM project page (just for grins I bolded all the documents):

This project represents the largest proposed onshore wind energy facility in North America (my bold); when fully operational; the project will be capable of generating up to 3,000 megawatts of clean, renewable power, enough to power nearly one million homes.

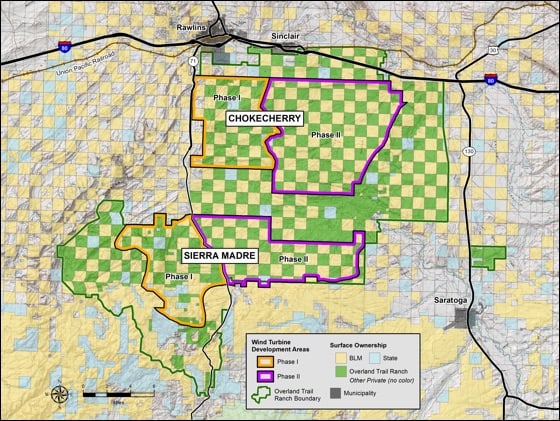

In March, the BLM prepared and released for public review an EA analyzing the potential impacts of constructing and operating 500 wind turbines on mixed ownership land. After reviewing public comments, the BLM has now refined and improved the analysis in the EA, which tiers to a 2012 Environmental Impact Statement that the BLM prepared to evaluate the potential impacts of the project as a whole.

The BLM administers approximately half of the land associated with the project site; the remainder of the site is made up of privately owned and state lands. Only a portion of the total land area would be used for or disturbed by the project. No ground-disturbing activities associated with the turbines can begin until the BLM issues a Right-of-Way (ROW) grant and Notice to Proceed.

The Power Company of Wyoming LLC (PCW), which will develop and operate the project, has consulted closely with the BLM and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to design an Avian Protection Plan and an Eagle Conservation Plan for this project. These plans include measures to avoid, minimize and compensate for impacts to avian and bat species. In addition, the project will avoid Sage-Grouse Core Areas and includes a conservation plan that accommodates ongoing ranching and agricultural operations. The developer also will avoid sensitive viewsheds in the project area to protect tourism and outdoor recreation values. Permits to build the project will be contingent on implementation of wildlife protection measures.

In addition, the BLM will coordinate issuance of a Notice to Proceed for Phase I of turbine development with the FWS’s decision regarding issuance of an Eagle Take Permit for Phase I of development. An Eagle Take Permit would allow for the non-purposeful take of eagles associated with construction and operation of the project. To support its decision, the FWS has prepared an Environmental Impact Statement to analyze the potential impacts of issuing an Eagle Take Permit.

A person has to wonder whether some of the federal analyses/permitting might have been combined and/or streamlined. But there are other issues as well:

No turbines have been installed and none will be available for installation for another three years. According to Jacobson, 2022 is being projected as the year when PCW would begin raising wind turbines. Jacobson stated the reason for the turbine’s delay is the project is waiting for transmission lines to be available to carry their power to consumers.

While 2024 is the projected date for the wind farm to start generating electricity, final completion is set to take a further two years, according to Jacobson.

The schedule and delay requests were the same as presented to the Industrial Siting Council earlier in the year.

Should the current dates hold, the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre wind farm project will have spanned more than a decade without including the enormous burden of planning the project.

And the transmission lines..?

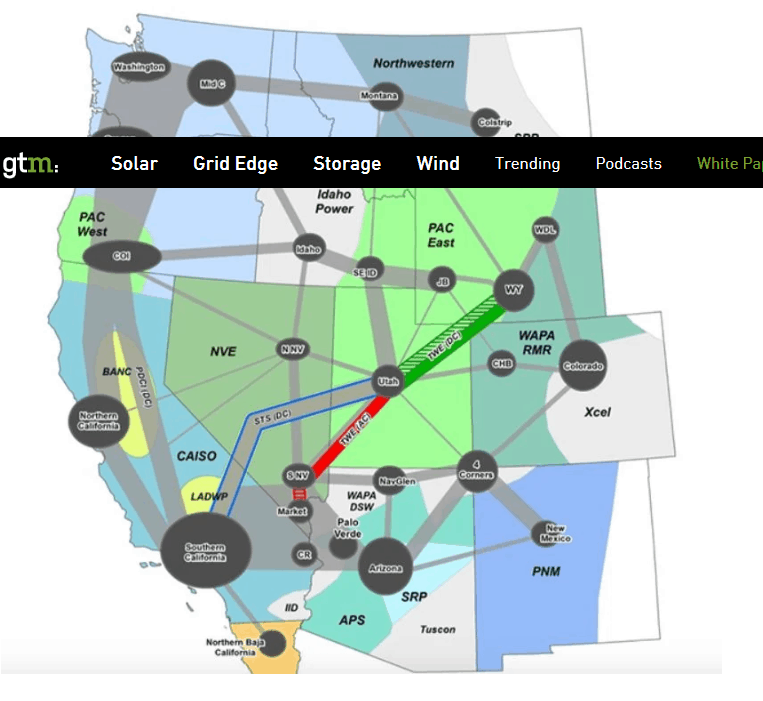

Besides the TransWest and Chokecherry projects, there are at least two other transmission projects being worked on to carry power from Wyoming westward, including the Zephyr Power Transmission Project, which has been in the works since 2011, and the proposed Gateway West and Gateway South projects from utility Rocky Mountain Power.

About two-thirds of the TransWest route lies on federal land, Choquette noted, and the process of obtaining the federal environmental analysis, rights-of-way, easements and licenses to build on that land stretched from 2008 to last year. Wyoming was the last state in its path to grant approval, and the project now has to secure approval from the counties in Utah and Nevada it will cross before it can be built, she said.

These kind of operational timeframes don’t bode well for climate targets that need large renewable contributions from federal lands to hit 2030 targets.

It actually sounds like the processes are working the way they were intended, but that’s an interesting observation about needing to speed things up, and I suppose there are some alternative responses. One is to “streamline” the process. Some of what Trump has been doing with cutting environmental corners would probably help renewable energy, but someone who actually believed in climate disruption (and wasn’t beholden to carbon fuel interests) might target renewable energy differently. Another option would be to just make it a higher priority for resources to get it done faster – more money to make more people make this goal their only priority. That wouldn’t necessarily mean less environmental protection from these developments. Of course there are people who don’t like the government spending more money (especially on things like climate “hoaxes”).

Hmmm. I suspect that much slowdown is when things get passed from agency to agency. It might be hard for FWS to drop everything to work on solar and wind projects when they are under court orders to reanalyze many other things. I’m a veteran of multi agency disagreements/fumbling as I have expect are you.

If there are court orders to reanalyze other things, that only means that those things might have to wait longer before they can proceed. Plaintiffs trying to stop things aren’t going to complain. It’s just a matter of agency priorities (and aligning them across agencies, which yes can be a problem). (Litigation to force ESA listing should also get priority treatment, but they’re always on a slow track.)