Coasts tend to have wetter forests and ideas like “leaving forests alone is the best thing for them” tend to have more of a grip there, because naturally (generally) they would just go on and on until some non-fire disturbance happens.

The history and funding of forest science has had a coastal bias in itself. For example, at Pringle Falls Experimental Forests in the early 80’s, we (the Area 4 Central Oregon silviculture folks) had a class taught by (terrific professors!) Bruce Larsen and Chad Oliver. We studied many models of species that were light limited; there were no models of trees that were water-limited. In our area, also, we hired a full-time reforestation specialist to experiment with planting, as the information we received from Doug-fir country didn’t work for drier areas.

It made some sense at the time to have that focus, as folks on the West side did more intensive management, and there was money related to that. However, we might ask if that coastalism still fits the needs of Oregon, given the overwhelming need to deal with fuels and living with fire in the fire-prone parts of Oregon. Which actually may compose more acres in the State.

Now, I don’t intend to give folks at OSU a hard time. My own Ph.D. professor, Tom Adams, was an OSU prof. They do terrific work. But it’s legitimate to wonder if OSU were located in Baker, or John Day, or even Bend, would the science produced be different? And of course, funding sources like NSF may also have a coastal bias. Since we don’t tend to look at things with that abstraction in mind, we might not observe it.

I wonder if the East Side 21-inch rule might never have been put in place were it not for West Side ideas about old growth colonizing (the idea, that is, not the old growth trees) the East Side? It took almost 30 years for folks on the East side to do their own research and find out…er… it doesn’t work? (We have applauded this co-designed and co-produced research on TSW before). I never thought of it as an antidote to Coastalism in science before.

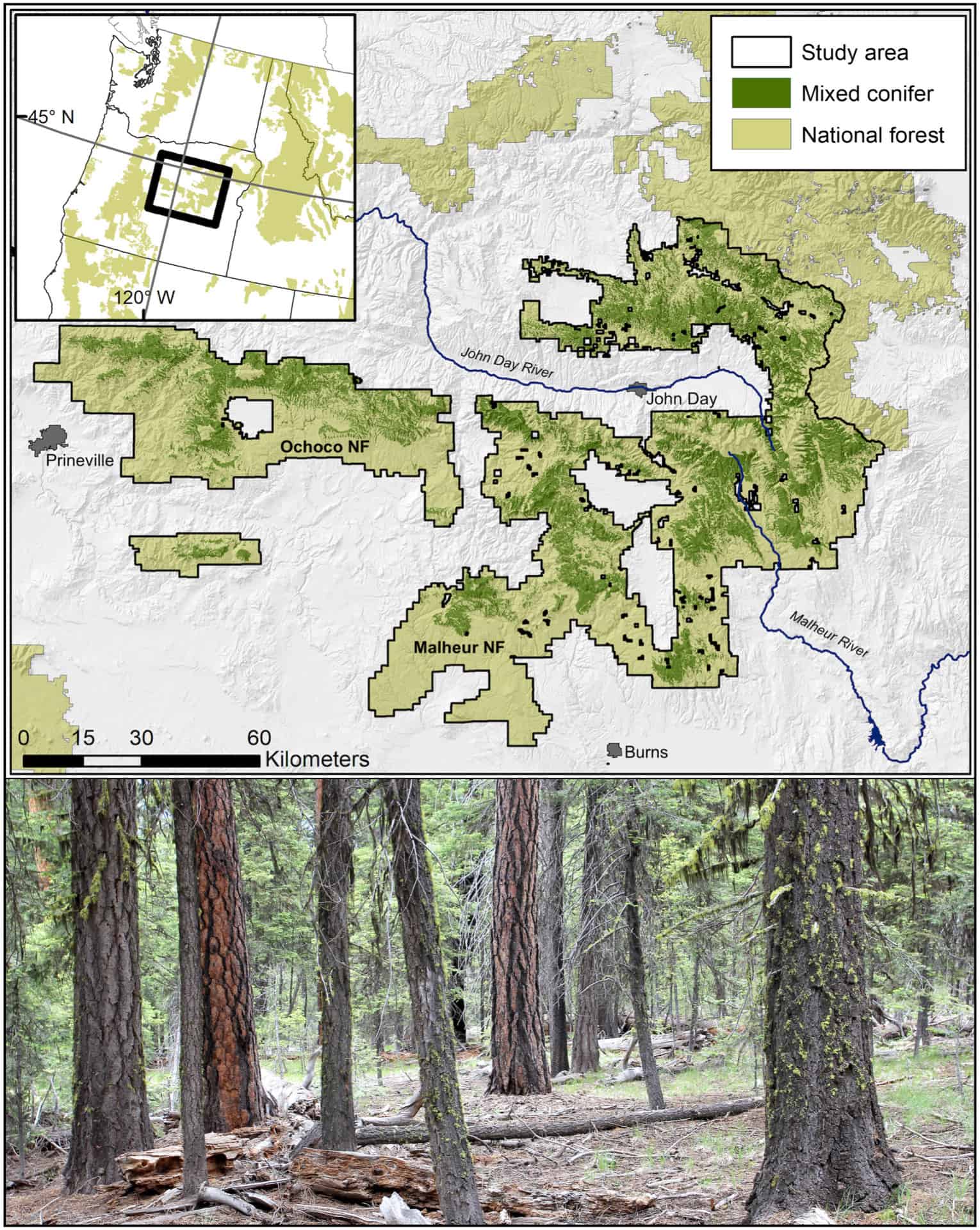

Anyway, here is a news story (thank you NAFSR!) on the findings of the study.

“Historical conditions were much better suited for old growth trees,” said Johnston. “Since we began to suppress fires that maintained open stands of widely spaced old trees, competition from young trees, including fairly large fir that established in the absence of fire, is killing old growth trees faster than they can be replaced.”

Diameter limits were widely adopted by Forest Service managers throughout the 1990s, Johnston said, in the face of social and legal pressure to conserve old growth habitat. Eastern Oregon’s diameter rule was supposed to be temporary as the Forest Service put together a comprehensive ecosystem management plan, but that process stalled, meaning the 21-inch rule is now 25 years past its original sunset date.

“With the Forest Service’s 21-inch rule for eastern Oregon, even stands that could be restored to their historical basal areas still had a lot more shade-tolerant trees than they did historically,” Greenler said. “But allowing the larger shade-tolerant trees to be removed helps reduce competition around old growth trees and improves their chances in the face of future stress.”

Here’s a link to the Ecosphere paper which is open-source. Thank you, Johnston et al.! And all the partners!

It is a lack of fire that allows the grand/white fir to invade and exist. Also possibly a response to climate change. Harvesting does not replace fire in these ecosystems. Chad Oliver is an arrogant and ignorant individual.

Professor Chadwick ‘Foghorn Leghorn’ Oliver is a living dinosaur–one of the most misogynistic individuals I’ve ever met. Also, Corvallis is not on the coast and OSU also has a campus in Bend that hosts a robust natural resources curriculum.

The ideas put forward above are weak and expressing them in a forum like this tends to exacerbate social and cultural divisions that are already rending our nation. It feels like filler content to me and probably ought to be outright ignored. If only I had the will!

OK I’ll bite.. I defined “coast” as anything west of the Cascade or Sierra crest. The east coast is more complicated.

I never noticed anything particularly misogynistic about Chad. In fact, he asked me why it appeared that PNW would not hire his highly capable graduate student, Ann Camp, who was working at the Wenatchee Lab. I helped review the Station at one time in the 90’s and their female science hiring was pretty bad.) Fortunately, Yale hired Ann and she has recently retired.

However, my point was that Bruce and Chad really know their stuff, and are leaders in the field (of silviculture) and when I asked “but what if light isn’t limiting but moisture is?” they were taken aback because I don’t think they thought much about those ecosystems.

OSU does now have a campus in Bend, but during my time there was COCC and the Bend Silviculture Lab. I wonder what the ratio of FTEs in research, extension, and education is between the two campuses (campi?). I’ll note that everyone in leadership seems to have a 541 area code. https://directory.forestry.oregonstate.edu/college-administration

I don’t think I’m “exacerbating social and cultural divisions”- I’d say I’m questioning structures of power and privilege.

I think all people are basically good but some voices tend to be heard more than others. And I wonder why. It’s only by listening to other points of view and understanding that tensions are reduced. And working together as per Susan and the folks on this research project.

On the Ochoco and the Wallowa-Whitman NF there was a plan developed in the 1970s to favor grand fir for timber production due to its fast growth. There were many areas where pine and larch were removed to “release” the grand fir understory. The problem with this approach became apparent after about 6 years of drought followed by a spruce budworm outbreak. So, it many places the predominance of grand fir is due to active management to promote it, not lack of fire.

Yup I remember that time. I worked peripherally on that plan. We were using the “best science” at the time which was Forplan a linear programming tool. We in silviculure and the entomologists always knew this wouldn’t work. The understory was already there to be released though, if we hadn’t cut the pine ( which didn’t happen everywhere). There would still be a fir underst

ory with high fuel loads and ladder fuels.

Plus I’m not sure how much or how long that was in vogue. It certainly hasn’t been for maybe 30 years? Maybe someone here has recent experience?

I cringe when reminded that there was a time when the Forest Service regarded FORPLAN as “science.” Relying on FORPLAN to make stand-level silvicultural decisions is also just plain silly. That’s never what it was designed to do.

Andy, I think it’s more complicated than that. Forplan was a tool developed by scientists to help make planning. Here’s what I found online by Norm Johnson.(1992) https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-4382-3_12

“Long-term planning models for the national forests have focused on determining sustainable levels of timber production over time. Recent forest planning modeling has sought economically efficient harvest schedules under broad constraints, while leaving it largely for plan implementation to discover whether the prescribed actions fully meet the variety of environmental objectives in the plans. ”

The true fir thing must have been an artifact of “economically efficient harvest schedules.” But.. I remember the two Forplan gurus I worked with were Bill Anthony on the Deschutes and John Cissel on the Ochoco. They may be around somewhere to ask for a better history.

So… if scientists develop tools to help the FS now, they aren’t “science” either? Or can we agree that what science gets employed in developing tools is a function of the way the issue was framed in the first place?

Remember the Eisenhower Consortium, circa 1979-80? As one of its hired hands, I helped teach the Forest Service how to use FORPLAN. If someone used it to make stand-level silvicultural decisions, that would be malpractice.

As for what is and isn’t “science,” don’t get me started! 🙂

I doubt whether those folks were “malpracticing”.

No I don’t remember that, I was just a humble Area Geneticist at the time, so it’s altogether possible that my memory is off and/or hall talk was not really correct (!).

I’ll put some retiree feelers out to see if anyone has better memories.

These pieces don’t fit. In the ’70s, there would not have been any completed forest plans that used FORPLAN (though there may have been timber planning models that didn’t seriously account for conflicting uses). And the language quoted from Norm Johnson clearly says that implementation of forest plans was intended to be a different process – not the FORPLAN forest planning model. But I agree that maximizing economic efficiency under the Reagan administration (1980+) would have said to grow what you can grow the fastest. (But I was only a FORPLAN practitioner/forest economist on two forests for 8 years.)

After the high levels of mortality from spruce budworm, that practice was discontinued, but the legacy of that era is still there with simplified species diversity. The community and institutional memory of that era is gone, so there are some who believe that those remaining grand fir stands are “natural” and do not realize the active management that was done to create them.

Thanks, Anonymous. It wasn’t that long ago (40 years?) that I remember the big Spruce Budworm Program. I think it would be a terrific idea if retirees in the Blue Mountain area wrote some of that history, including the project areas and prescriptions.

Kathleen, I’m not getting your point. That if we had run fire through these stands a while back we wouldn’t have the situation we have today? We should just let them burn even though it will now burn up the big pine trees and start over?

I don’t think it’s a response to climate change, as we knew this long before people were aware of it.

See my answer about Chad below.