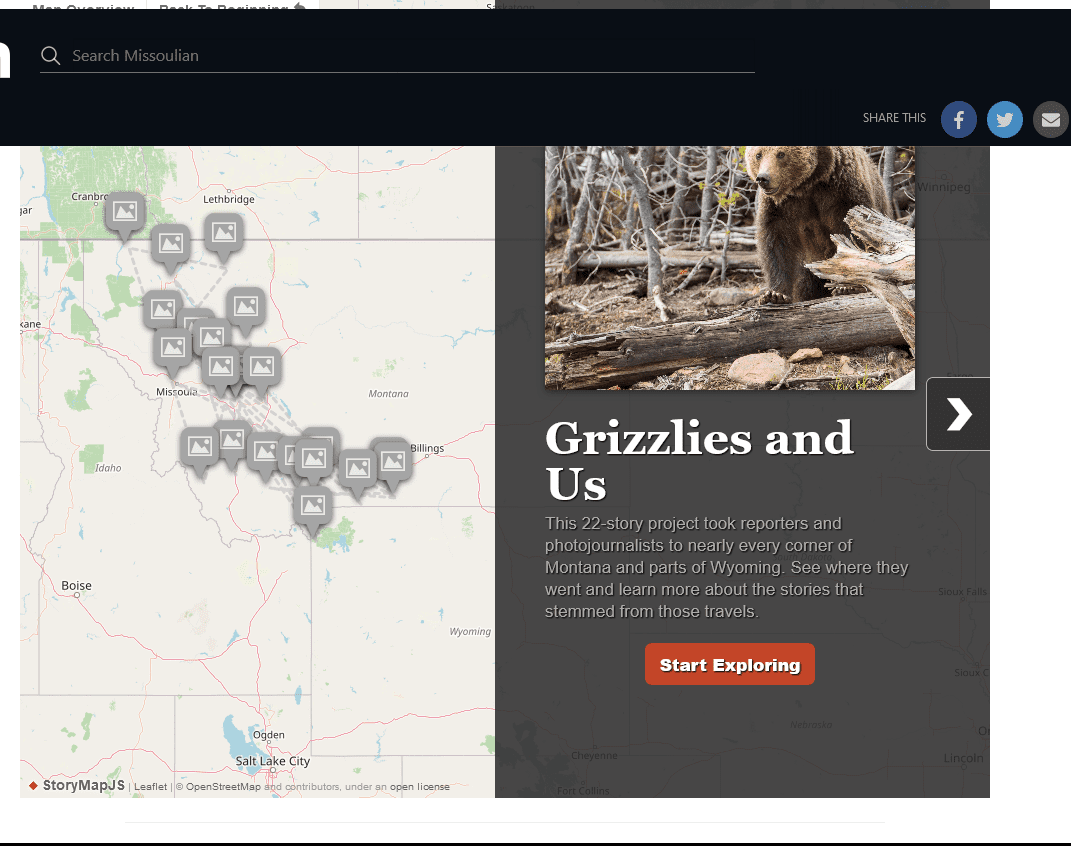

Here’s a really interesting series in the Missoulian. It’s it’s a 10- part series comprised of more than 20 stories. Lots of stories and they seem to be visible to those without a Missoulian subscription (thank you, Missoulian! and Lee Enterprises!)

I picked this one as the bikes/grizzlies issue seems to be of interest to TSW readers, but there are many others.. feel free to discuss any. Here’s one about livestock guardian dogs and technology protecting sheep, and the work of ranchers and the group People and Carnivores.

Grizzlies are expanding their range.. how are people getting along with them?

US Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Wayne Kasworm had just replaced Servheen as interim leader of the grizzly recovery effort. Treat’s death crystallized one of his top tasks: Getting people to agree on how much safety they all must give up to coexist with bears.

“They’re wild animals, and we are not controlling them,” Kasworm said. “What we attempt to do is provide information so people can make reasoned judgments about what is safe activity or not safe activity. We’re trying to get some conversation going, to get people thinking about what is going on out there in the woods.”

To deal with objective dangers in the outdoors, people already self-limit their recreation in many ways. Boaters avoid rivers during spring runoff, or accept the consequences of lost gear, wrecked boats, and possible death. Golfers voluntarily leave the links when a thunderstorm brings lightning over their metal clubs and spiked shoes. Snowmobilers and backcountry skiers check avalanche forecasts and weigh the risks of the day’s adventure.

“We’re trying to get folks to recognize and take on responsibility for their own safety when they walk into known grizzly bear habitat, when grizzly bear habitat is taking over more and more of Montana,” Kasworm told me. “When a bear results in a human safety issue, or it’s killing livestock repeatedly, we remove the bear. But if you’re tooling around on your mountain bike and you bump into the bear and you’re scared, that’s not necessarily a reason to remove the bear.”

Is it a reason to remove the bikes? And what about everything else humans like to do in bear country? Whose interests rule?

Three years to the day after Treat’s death, Flathead National Forest Supervisor Chip Weber declared his disagreement with Servheen’s report. New controversy had arisen over a commercial ultramarathon and a backcountry bike shuttle service in the national forest land around Whitefish, Montana, about twenty miles from Coram.

“I want to start by strongly repudiating the notion that as an agency, we ought not promote, foster or permit activities because engagement in those activities presents risk to the participants,” Weber told the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee’s summer 2019 gathering in Missoula. “The issues around this are much broader than trail use, and grizzly bears and both people and wildlife may suffer if the discussion isn’t expanded.”

As to Board of Review report, Weber told me he had great personal respect for Servheen but “his (Servheen’s) focus is grizzly bear recovery and solely grizzly bear recovery. Mine is serving the American public and the needs they want in the context of many wildlife species and an overall conservation mission that’s very, very broad.”

Individual sporting events like the Whitefish ultramarathon have such minimal impact on grizzly bears, Weber said, they fall under a categorical exclusion from in-depth environmental review. At the same time, those events endear increasing numbers of people to their public lands as the number of users grows year after year.

“There’s a broad public out there with needs to be served and not just the needs of the few,” Weber said. “We think that greater good for the greatest number will be served. That fosters connectivity with wildlands and a united group of people that can support conservation. And the best conservation for bears is served by figuring out how to have these human activities in ways that are as safe as they can be, understanding you can never make anything perfectly safe.”

Darwin sometimes works in unforgiving ways.

I always thought that when you are out and about one should be aware of their surroundings, and also be responsible for one’s own safety. People want to ride bikes such that they crash into big grizzlies at full speed, well, have at it. I notice in the story the cousin watches and then goes away. No mention of bear spray, let alone the ubiquitous 10 mm that many guides and hunters seem to carry these days.

I skimmed the articles and they all seemed of a type. No comparisons to AK where they have many years experience dealing with bears, probably doesn’t fit well with the “narrative”. Lots of generalisations about what biologists think. Only poll referenced said Montanans overwhelmingly support hunting bears. Can’t wait until we get some in Colorado.

I read a Q and A about large carnivore management from an environmental justice perspective. The interview was with Alex McInturff, an assistant professor in the UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences.

In the interview Alex identifies 4 components of environmental justice that should be considered in regards to reintroduction of large carnivores.

1 Distribution considers who is actually being harmed materially and who is benefiting

2 Participation asks who has a seat at the decision-making table

3 Recognition asks whose worldview is being recognized in the terms of the debate or in the discussion itself

4 And finally, affective (or emotional) justice considers how we appropriately account for people’s emotions — fear, anger, happiness, for example — toward the reintroduction of certain species

For his next project he’d like to consider a potential reintroduction of the grizzly into CA as has been proposed.

Thanks Som and Anonymous! These are worth their own post so others can see. So I will.

Oops, link.

https://www.washington.edu/news/2022/01/11/qa-bringing-a-justice-lens-to-wildlife-management/

His paper is pretty readable too. Love the way he tosses in all the most recent DEI jargon.

About the same time this series in the Missoulian started, the states adjacent to the Yellowstone recovery area petitioned to delist the Yellowstone population of grizzly bears as a distinct population segment that has recovered.

https://www.mtpr.org/montana-news/2022-01-12/wyoming-petitions-federal-government-to-delist-yellowstone-grizzly

And immediately after that, pretty much all the Montana biologists who deal with grizzly bears opposed delisting (a reversal of their positions for some) because of changes in state law that would allow more grizzly bears to be killed.

https://mountainjournal.org/prominent-scientists-say-removing-grizzly-bears-from-federal-protection-in-west-is-bad-idea

The Forest Service could of course prohibit all these things on national forests, but I don’t hear anyone suggesting that.

They don’t mention the legal problem with delisting a DPS. Under ESA, distinct population segments are a tool to list only part of a species population that warrants listing, when the species as a whole does not. Not to partially delist a species that still qualifies as threatened or endangered. (And there’s questions about whether the Yellowstone population can even be considered distinct.)

John I went and looked at your article in The Mountain Journal. (I have to admit I’ve never read anything I found favor with there.) I read through the list of biologists all retired. You say that’s all the biologists? No biologists in Montana that aren’t retired? I call BS. That’s the 1% of biologists, I can make up numbers too.

This part at the end and in bold really grabbed my attention.

“It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to realize that if grizzly bears were delisted and turned over to state management, that the Montana legislature and governor would do the same thing to grizzlies that they are currently doing to wolves—they would likely try to legislatively minimize grizzly numbers inside recovery zones and eliminate most grizzlies outside recovery zones.”

I mean my gosh, so what? If the people of montana want to manage wildlife in a certain way, well let them have at it. Who are all those pointy headed types to tell people what to do? After 25 years one would think all those brilliant minds would kind of get the idea, their hobby just doesn’t set well with those who are adversely affected. I certainly haven’t heard of Montana running out of wolves.

You’re right that this can’t speak for the bear biologists who are still working and afraid to publicly sign on, but I can’t imagine very many would disagree with this respected group of experts.

An interesting point about recovery zones. If that was all they need for recovery, then maybe it wouldn’t matter what happened to the bears that strayed outside of them. But the recovery plan also requires connectivity for recovery, which means leaving bears alone enough for them to move between recovery areas. That, as well as increased demographic risk of smaller populations (a big consideration for grizzly bears) are relevant to ESA designation.

Jon, maybe you can explain… if recovery zones are what they need for recovery, and they need connectivity, why don’t recovery zones have corridors between them (among them?) and they why aren’t the combo of areas and corridors as a whole called “recovery zones”?

The recovery plan was written in 1982 and revised in 1993, and that’s not how the FWS chose to write it back then – partly because they didn’t know where to put the corridors (see below). I think most experts agree that is no longer based on the best available science, but a lawsuit to compel an update was rejected because ESA doesn’t require updates to recovery plans (which are considered non-binding on other agencies).

Thanks for making me take a second look at the recovery plan, because it doesn’t explicitly say connectivity is “required.” The current recovery plan required an assessment of linkage areas, but said, “Linkage zones are desirable for recovery, but are not essential for delisting at this time.” However, “It is essential that existing options for carnivore movement between existing ecosystems be maintained while the evaluation of linkage zones is underway.” And, they would be used “as the basis for future linkage zone actions” (p. 25). I worked on how to incorporate the results of that assessment into forest plans (which got little traction in the Forest Service) with the understanding that it was necessary for recovery – but I don’t know what the FWS position is on that question now in the absence of an updated recovery plan.

Also, the 1993 recovery plan discussed artificially relocating grizzly bears for genetic reasons, but I don’t think can be viewed a substitute for the habitat-based recovery that ESA requires.