If you’ve been following the coverage of energy needs and why gas prices are high, as the war in the Ukraine has caused concerns about disruptions to energy in Europe, the U.S. and other places, it seems like both the coastal media, ENGO’s and oil and gas producers are, naturally, telling different stories. Can we parse these out and see some of what the facts tell us, and what the federal lands have to do with it? I’m hoping that people more knowledgeable than I on these topics can contribute. Fortunately both the BLM and EIA have easily accessible data, so we should be able to draw our own conclusions. I’d also like to go back to an old post featuring Michael Webber, a mechanical engineering professor:

Take climate change: When scientists and environmental activists take stock of the mess we are in, the oil and gas sector is a handy villain. For people tapping into their instinct for retribution, the petroleum industry ought to be punished for the damage it has caused and cut out from any opportunity to participate in the upcoming transition to a clean energy economy.

Later in the article, he says:

But blaming the industry leaves out our own culpability for our consumptive, impactful lifestyles. Oil consumption is as much about demand as supply.

I received an email from the Sierra Club “URGENT: Fossil fuel leasing on public lands is destroying the planet.” So let’s look at their claim from the demand side.

The WaPo has an article from March 8 describing where countries can go to replace oil from Russia. It’s got some interested charts. According to them,

This is a daunting task, especially since global demand for oil is expected to climb 3.2 million barrels a day in 2022 to a total of 100.6 million a day, according to the International Energy Agency’s most recent monthly report.

I think these discussions are confusing, for one reason, because people don’t necessarily separate oil from natural gas when people talk about “fossil fuels.” And the second thing is that production, workforce, investments, facilities and so on (plus markets) are extremely complicated. It’s dubious as to whether most of the people talking about stopping fossil fuels understand the mechanics of all that. So there is a gap between the talkers and writers, on the one hand, and the doers, on the other hand.

So if we’re to examine the Sierra Club’s claim, first we would look at how much oil and natural gas is actually produced on federal lands?

Here’s what BLM says:

For fiscal year (FY) 2018, sales of oil, gas, and natural gas liquids produced from the Federal and Tribal mineral estate accounted for approximately 8 percent of all oil, 9 percent of all natural gas, and 6 percent of all natural gas liquids produced in the United States.

Another problem with our understanding, besides the oil/natural gas difference, is the onshore versus offshore difference. Clearly they are different in both environmental impacts, and affected and concerned states. And people who round up the numbers don’t use the same years. But we can still see a general outline of the picture.

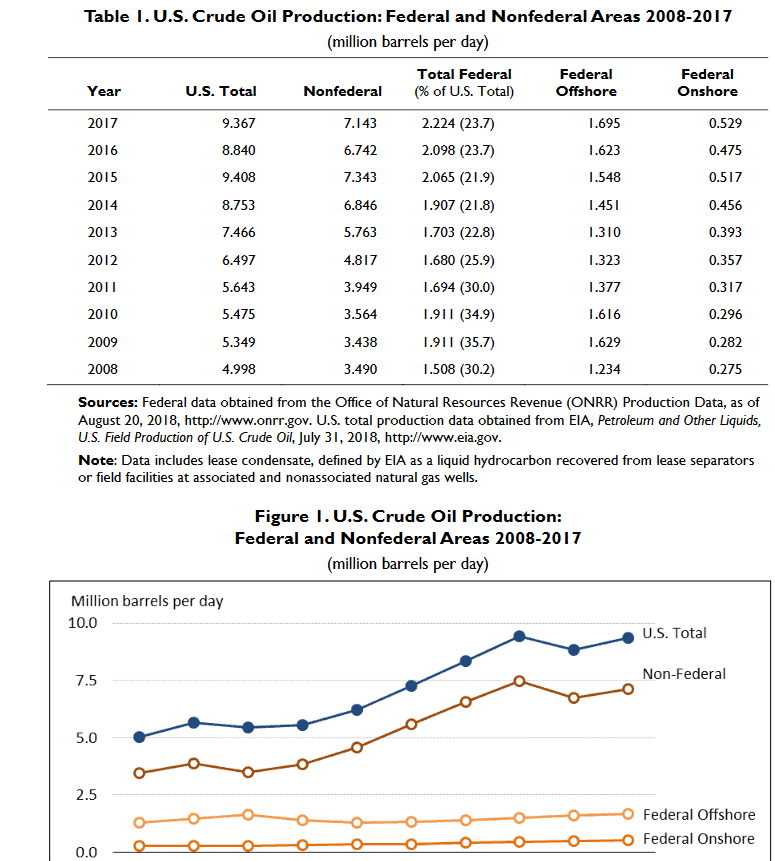

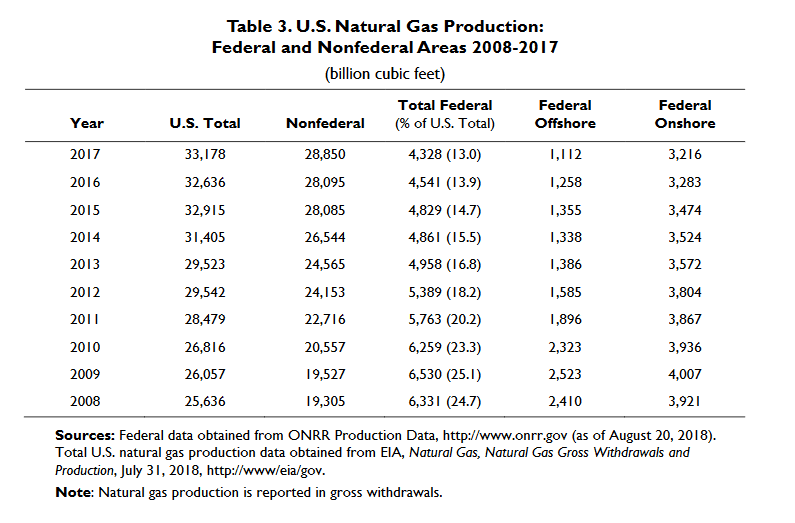

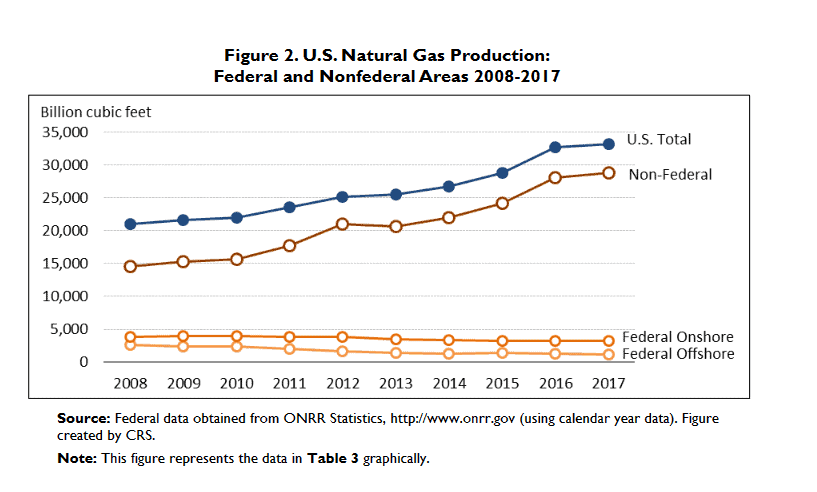

Conveniently, our friends at the Congressional Research Service published a study in 2018 with a handy table.

Now, I’m definitely not an expert on this, but it’s interesting to me how little the onshore produced compared to private and offshore federal. It’s 5% of domestic oil production. Using the same numbers, for 2017, I came up with 10% for onshore natural gas. (Total of domestic production for all federal was 13% for gas).

But what did the US consume in oil and natural gas? According to the EIA,

In 2021, the United States consumed an average of about 19.78 million barrels of petroleum per day, or a total of about 7.22 billion barrels of petroleum.

and

The United States used about 30.5 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas in 2020, the equivalent of about 31.5 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) and 34% of U.S. total energy consumption.

I’d have to say that I can’t agree with the Sierra Club that federal land fossil fuel extraction is “destroying the planet.” It seems like a relatively small piece of the national (no to speak of the planetary) puzzle. It’s also helping out poorer states with bids and royalties, which seems like social justice.

You can check out revenues to states and counties, as well as Native Americans, on this handy DOI website.

I’d like to give a big shoutout to BLM, the Natural Resources Revenue Data folks, and EIA for making my work on this topic relatively easy.

And circling back to the WaPo article, an Admin that favors equity and social justice, it seems logical to me, would prefer production and the associated benefits to accrue to say, Louisiana, rather than to Saudi Arabia, Iran, or Venezuela.

Hyperbole is the way the game is played these days; fear is what motivates people. Thank you for also illustrating that federal oil and gas leasing is a non-issue in terms of gas prices, which debunks the “drill, baby drill” crowd’s arguments as well.

I’d also resist the urge to characterize anything that creates American jobs as “social justice.” Maybe we need a definition of that; here’s one (from “Oxford Resources”): “The objective of creating a fair and equal society in which each individual matters, their rights are recognized and protected, and decisions are made in ways that are fair and honest.”

Well here’s the one I’m familiar with…noun: social justice

justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society.

If we knowingly send blue collar jobs overseas that has an unequal impact .. first because those jobs are lost (while we buy products with the same or more environmental impacts) and second because the taxes we would have collected go to things that the state government funds, including funds for social goods.

But perhaps you’re right it’s not social justice..just a bad deal for blue collar folks, their families, and their communities.

Just between you and me 🙂 (since this is straying beyond our blog territory), “justice” is often in the eye of the beholder, and so it seems to be more useful for posturing than policy-making.

But ENGOs and others frequently use the term “environmental justice” so I think we need to open the discussion up to all interpretations of the abstraction.