More grist for our continuing discussion of future forests and climate change. An open-access paper in Environmental Research Letters, “Biomass stocks in California’s fire-prone forests: mismatch in ecology and policy.” In essence, the authors suggest a shift in policy, based on likely forest-carbon scenarios, is in order.

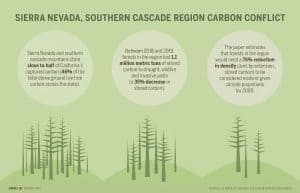

A PR about the paper notes that “….between 2018 and 2019, forests in the region lost 1.1 million metric tons of stored carbon to drought, wildfire, and invasive pests. That loss represents a 35% decrease in stored carbon and calls into question the feasibility of California’s long-term carbon policy.”

This illustration accompanies a UC Berkeley article about the paper:

Much of this region is federal land, so the question for us here on Smokey Wire is how the USFS is to move forward with forest planning and management, given this scenario.

Abstract:

Restoration of fire-prone forests can promote resiliency to disturbances, yet such activities may reduce biomass stocks to levels that conflict with climate mitigation goals. Using a set of large-scale historical inventories across the Sierra Nevada/southern Cascade region, we identified underlying climatic and biophysical drivers of historical forest characteristics and projected how restoration of these characteristics manifest under future climate. Historical forest conditions varied with climate and site moisture availability but were generally characterized by low tree density (∼53 trees ha−1), low live basal area (∼22 m2 ha−1), low biomass (∼34 Mg ha−1), and high pine dominance. Our predictions reflected broad convergence in forest structure, frequent fire is the most likely explanation for this convergence. Under projected climate (2040–2069), hotter sites become more prevalent, nearly ubiquitously favoring low tree densities, low biomass, and high pine dominance. Based on these projections, this region may be unable to support aboveground biomass >40 Mg ha−1 by 2069, a value approximately 25% of current average biomass stocks. Ultimately, restoring resilient forests will require adjusting carbon policy to match limited future aboveground carbon stocks in this region.

I wonder how the Dixie and Caldor fires (among others) affect the carbon accounting and longterm strategies, now. We cannot just allow ‘whatever happens’ to happen in our forests.

There’s a problem in dry forests with “keeping trees around” as a carbon policy- they tend to burn up. Or die from something and then burn up. And possibly not grow back.

As for me, I’d pick other carbon reduction options that don’t depend on the kindness and stability of Mother Nature.

This helps define desired future conditions and suggests a course of action. Of course, there will be opposition…

Mother Nature moves continents, raises mountains, grows tropical rainforests around the world and then buries them under miles of glaciers. Seashells that once were underneath an ocean that can be found at altitudes where oxygen becomes scarce… And then there is us… Fighting over what to do over a problem we apparently “caused” in 250 years of industry? We managed our way into this mess, might as well manage our way through it. I doubt any of us will be around to see the day when we actually clean it all up, if that’s even a realistic expectation.

I am not sure I understand what those other options are? The other options have to be feasible and scalable. How does one treat a fire-prone landscape that includes large areas that are not economically or operationally feasible for non-fire treatments?

Sorry A, I was off in carbon reduction land.. not forest land.. I was thinking of technical carbon removal schemes in which people have more control over the outcomes.

I’m in favor of treating the fire-prone landscape and using the material thereby obtained in a carbon-helping way. I’m in favor of trees, and for planting post fire, and for maintaining stocking for drought and fire resilience.

I’m just not in favor of depending on trees themselves continuing to suck carbon out of the air as a carbon reduction policy.. too many uncontrollables and unknowns compared to other alternatives. Hope this is clearer.

“Ultimately, restoring resilient forests will require adjusting carbon policy to match limited future aboveground carbon stocks …” I think that’s a normative conclusion that prioritizes resilient forests over carbon reduction. Why shouldn’t we adjust forest “resilience” policy by also considering the relative carbon gains from retaining more density than would be the desired condition for “resilience” (factoring in fire risk as appropriate)? This sounds to me more like a sliding scale that would be hard to draw general conclusions about.