This is a guest post by Jim Furnish.

Commentary: Counteracting Wildfire Misinformation, by Jones et al 2022: Response

I recently read and reflected on Commentary, a piece from a well-intentioned group of authors, in which they attempt to bring clarity to efforts to identify solutions and responses to the

increasing impact on wildfires on homes, communities and wild lands. They appropriately titled their contribution as commentary, as I find it long on opinion and short on facts. Any time one

sets out to discern what constitutes “misinformation” they should have facts on their side, lest they be just one more voice suggesting they alone are credible, as is the case here.

First, let me lay out incontrovertible truths and observations. Climate change is upon us and increasing wildfire activity in both human communities and large swaths of forest, particularly the American West. Rising temperatures and prolonged drought have lengthened fire seasons and, along with strong wind events, have led to many large fires that are too often becoming destructive to human communities. Costs of fire suppression have risen dramatically, with little correlation to reduced acres burned. Nor have we experienced reduced risk to communities and development near and within forests, in spite of increasing investment. Fire science has made dramatic gains in recent decades, yet forest fires present an enigma: how can we bend the curve of escalating cost and losses, for both natural resources and urbanized areas?

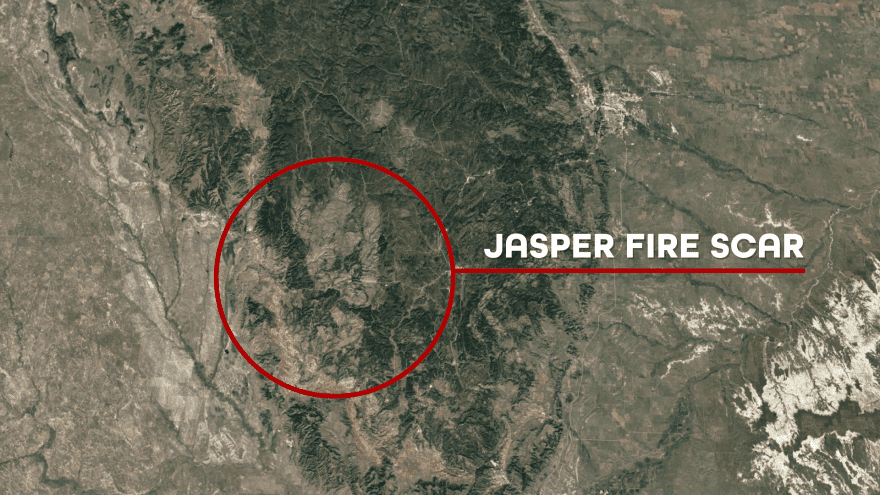

The authors of Jones et al suggest that part of the problem is misinformation, and ask us for their faith that they alone are the arbiters of what is true and what is working. Let me begin by citing the large Jasper Fire, in SD’s Black Hills National Forest, circa 2000. Jasper Fire burned almost 90,000 acres of intensively managed Ponderosa pine forest, about 10 percent of the entire national forest. Human caused, it was ignited on a hot, dry, windy July day – quite typical of weather in peak burning periods nowadays. Suppression efforts were immediate and used every tool in the agency’s tool box… to no avail.

Notably, the burned terrain exemplifies what we consider the best way to fire proof a forest. This mature forest of small sawtimber had been previously thinned to create an open stand

intended to limit the likelihood of a crown fire. Yet, the fire crowned anyway and raced across the land at great speed, defying control efforts. Much of the area remains barren 20 years later,

while the Forest Service slowly replants the area.

I cite this example, because it represents precisely what agencies posit as the solution to our current crisis: 1) aggressively reduce fuel loading through forest thinning on a massive scale

of tens of millions of acres (at a cost of several $billion), while trying to 2) come up with sensible answers about how to utilize woody material that has little or no economic value; and 3)

rapidly expanding the use of prescribed fire to reduce fire severity. These solutions are predicated on the highly unlikely (less than 1%) probability that fire will occur exactly where

preemptive treatments occurred before their benefits expire. These treatments are not durable over time and space, and only work if weather conditions are favorable, and fire fighters are

present to extinguish the blaze.

How does this relate to misinformation? To be blunt, the ineffectiveness of current practices has led many scientists to suggest, based on peer reviewed science and field research as

opposed to modeling, that agency “fire dogma” needs to be revisited. The call for a true paradigm shift is occurring both within and outside the agency. Several themes and truths have

emerged, for example:

1) Fires burn in ways that do not “destroy”, but rather reset and restore forests that evolved with fire in ways that enhance biodiversity.

2) Forest carbon does not “go up in smoke” – careful study shows that more than 90 percent remains in dead and live trees, as well as soil, because only the fine material burned.

3) The biggest trees in the forest are the most likely to survive fire, and thinning efforts that remove mature and older trees are counter-productive. We are seeing more cumulative fire

mortality in thinned forests, than in natural forests that burn.

4) Thinning and other vegetation removal increases carbon losses more than fire itself and, if scaled up, would release substantial amounts of carbon at a time when we must do all we

can to keep carbon in our forests.

5) If reducing home loss is our goal, experts are telling us that the condition of vegetation more than 60 feet from the home has nothing to do with the ignitability or likelihood a home will

burn. The best most durable investments to reduce home loss are focused on hardening homes in at-risk communities using proven fire wise technology.

6) Large, wind-driven fires defy suppression efforts and many costly techniques simply waste money and do more damage. Weather changes douse big fires, people do not.

Do the authors of the Commentary believe these scientific findings are misinformation necessitating “debunking and prebunking” based on their authors “collective experience in wildfire science.” Boiled down, their commentary suggests that they know best what constitutes valid information; that they are the self-appointed gatekeepers of fire science and truth.

My charitable judgment is that their belief that thinning forests to reduce fire severity may be effective sometimes at accomplishing that goal – if weather is favorable, when we don’t

have extreme wind and drought, and we have adequate firefighters on hand. Overall, however, this strategy is not working out well for human communities – as we have been at it for over

thirty years, and we are seeing increasing loses. While careful thinning can work in favorable conditions, the authors cannot and do not claim that their recommendations for careful thinning

are always faithfully implemented by the line officers in federal agencies. They cannot and do not say that careful forest management is occurring on private industrial lands that dominate

significant swaths of at-risk forestland in the Western United States, nor do they suggest that private industrial forests incur less fire losses. In fact, studies have shown that fires are often

worse on private forests. They spend no time identifying industry misinformation, which are often grossly oversimplified and pushed out to the public through well-funded campaigns.

The authors are dismissive of anything that questions their position, and uncomfortable with answering the hard questions about the costs and challenges of scale regarding landscape

vegetation management. No credible business plan exists for scaling up what they propose based on a full accounting of costs and operational challenges, and that is free from confirmation bias .

They also fail to acknowledge the scientific findings that efforts to control vegetation and fire severity in wet, western Cascade forests, for example, are unequivocally useless over space and

time because the forests quickly grow back.

I encourage authors to welcome contrary opinion and emerging science that does not conform to their collective experience. The nasty truth is that forest fires defy simple explanations and solutions. They ought to embrace paradox, not demand fealty. They ought to ask the tough questions, not claim that there are no questions to ask.

But one thing is quite clear – what’s been done and being done hasn’t worked well, and we are not close to pulling ourselves through the knothole of now. We need new thinking and new approaches that see fire management in context with climate change, forest carbon sequestration and storage, biodiversity, clean water and good air quality. New voices are as worthy of careful consideration as those authoring the subject commentary.

References

CITATIONS

Abatzoglou, J.T., Juang, C.S., Williams, A.P., Kolden, C.A. and Westerling, A.L., 2021. Increasing synchronous fire danger in forests of the western United States. Geophysical Research Letters, 48(2), p.e2020GL091377

Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P., 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 113, 11770-11775.

Bartowitz, K.J., Walsh, E.S., Stenzel, J.E., Kolden, C.A.,Hudiburg, T.W., 2022. Forest carbon emission sources arenotequal: Putting fire, harvest, and fossil fuel emissions in context. Front. For. Glob. Change, 5, 867112.

Calkin, D. E., Cohen, ). D., Finney, M. A. & Thompson, M. P., 2014. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. lll, 746-751.

Campbell, J.; Donato, D.; Azuma, D.; Law, B., 2007. Pyrogenic carbon emission from a large wildfire in Oregon, United States. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences, 112, G04014.

Campbell, J.L.; Harmon, M.E.; Mitchell, S.R., 2012. Can fuel-reduction treatments really increase forest carbon storage in the western US by reducing future fire emissions? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 83–90.

Cohen, J.D. 2000a. Preventing disaster, home ignitability in the wildland-urban interface. J Forestry 98(3):15– 21.Cohen JD. 2000b. A brief summary of my Los Alamos fire destruction examination. Wildfire 9(4):16-18.

Cohen, J.D. 2001. Wildland-urban fire—a different approach. Proceedings of the Firefighter Safety Summit, Missoula, MT. Fairfax, VA: International Association of Wildland Fire.

Cohen, J.D. 2003. An examination of the Summerhaven, Arizona home destruction related to the local wildland fire behavior during the June 2003 Aspen Fire. Report to the Assistant Secretary of the US Department of Agriculture.

Cohen, J.D. 2004. Relating flame radiation to home ignition using modeling and experimental crown fires. Canadian J ForRes 34:1616-1626. doi:10.1139/Xo4-049.

Cohen, J.D. 2010. The wildland-urban interface fire problem.Fremontia 38(2)/38(3):16-22.

Cohen, J.D. 2017. An examination of home destruction: Roaring Lion Fire. Report to the Montana Department of Natural Resources.

Cohen, J.D., Stratton, R.D., 2003. Home destruction. In RT Graham (ed). Hayman Fire Case Study. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-114. Ogden, UT: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 396 p.

Cohen JD, Stratton RD. 2008. Home destruction examination Grass Valley Fire. USDA R5-TP-026b. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/ pubs_other/rmrs_2008_cohen_j001.pdf

Coop, J.D., Parks, S.A., Stevens-Rumman, C.S., Ritter, S.M, Hoffman, C.M, 2022. Extreme fire spread events and area burned under recent and future climate in the western USA, Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2022;00:1–11.

Downing, W.M., Dunn, C.J., Thompson, M.P., Caggiano, M.D. and Short, K.C., 2022. Human ignitions on private lands drive USFS cross-boundary wildfire transmission and community impacts in the western US. Scientific Reports, 12(1), pp.1-14.

Evers, C., Holz, A., Busy, S., Nielsen-Pincus, M., 2022. Extreme Winds Alter Influence of Fuels and Topography on MegafireBurn Severity in Seasonal Temperate Rainforests under Record Fuel Aridity, Fire, 5, 41.

Harmon, M.E., Hanson, C.T., DellaSala, D.A, 2022.Combustion of Aboveground Wood from Live Trees in Megafires, CA, USA, Forests, 13, 391.

Hanson, C.T., 2022. Cumulative Severity of Thinned and Unthinned Forests in a Large CaliforniaWildfire, Land, 11, 373.

Hudiburg, T.W.; Luyssaert, S.; Thornton, P.E.; Law, B.E., 2013.Interactive Effects of Environmental Change and Management Strategies on Regional Forest Carbon Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13132–13140.

Hudiburg, T.W.; Law, B.E.; Wirth, C.; Luyssaert, S., 2011.Regional carbon dioxide implications of forest bioenergy production. Nat. Clim. Change, 1, 419–423.

Hurteau, M.D.; North, M.P.; Koch, G.W.; Hungate, B.A. 2019. Opinion: Managing for disturbance stabilizes forest carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 10193–10195.

Keeley, J.E.; Syphard, A.D., 2019. Twenty-first century California, USA, wildfires: Fuel-dominated vs. wind-dominated fires. Fire Ecol., 15, 24.

Levine, J.I, Collins, B.M., Steel, Z.L., de Valpine, P., Stephens, S., 2022. Higher incidence of high-severity fire in and near industrially managed forests, Front. In Ecol. & Env., 20, 397-404.

Mitchell, S.R.; Harmon, M.E.; O’Connel, K.E.B. (2009). Forest fuel reduction alters fire severity and long-term carbon storage in three Pacific Northwest ecosystems. Ecol. Appl., 19, 643–655.

Reilly, M.J., Zuspan, A., Halofsky, J. S., Raymond, C., McEvoy, A., Dye A.W., Donato, D.C., Kim, J.B., Potter, B.E., Walker, N., Davis, R.J., Dunn, C.J., Bell, D.M., Gregory, M.J., Johnston, J.D., harvey, B.J., Halofsky, J.E., Kerns, B.K., 2022, Cascadia Burning: The historic, but not historically unprecedented, 2020 wildfires in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Ecosphere, 13:e4070.

Rhodes, J.J.; Baker, W.L., 2008. Fire probability, fuel treatment effectiveness and ecological tradeoffs in western US public forests. Open For. Sci. J., 1, 1–7.

Schlesinger, W.H., 2018. Are wood pellets a green fuel? Science, 359, 1328–1329.

Schoennagel, T., Balch, J.K., Brenkert-Smith, H., Dennison, P.E., Harvey, B.J., Krawchuk, M.A., Mietkiewicz, N., Morgan, P., Moritz, M.A., Rasker, R. and Turner, M.G., 2017. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(18), pp. 4582-4590.

Solomon, S.; Plattner, G.-K.; Knutti, R.; Friedlingstein, P., 2009.Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 1704–1709.

Stenzel, J.; Berardi, D.; Walsh, E.; Hudiburg, T., 2021. Restoration Thinning in a Drought-Prone Idaho Forest Creates a Persistent Carbon Deficit. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences, 126, e2020JG005815.

Sterman, J., Siegel, L., Rooney-Varga, J.N., 2018. Does replacing coal with wood lower CO2 emissions? Dynamic lifecycle analysis of wood bioenergy, Environ. Res. Lett. 13 015007.

Syphard, A. D. & Keeley, J.E., 2019. Factors associated with structure loss in the 2013-2018 California wildfires. Fire 2, 1-15.

Syphard, A. D. et al., 2007. Human influence on California fire regimes. Ecol. Appl. 17, 1388-1402.

Zald, H. S. J. & Dunn, C. J., 2018. Severe fire weather and intensive forest management increase fire severity in a multi-ownership landscape. Ecol. Appl. 2, 1-13.

Zhou,D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, S.; Oeding, 2013. J. A meta-analysis on the impacts of partial cutting on forest structure and carbon storage. Biogeosciences, 10, 3691–3703.

Jim Furnish

Deputy Chief, USDA Forest Service (Ret.)

Author: Toward A Natural Forest (Oregon St Univ Press 2015)

Gila, New Mexico

Allowing ‘whatever happens’ to happen has also been proven to be horrifically wrong. Preservationists want a nationwide decree to end all logging, everywhere, as a ‘solution’ to all of our forest problems. Fighting against ignorant political ideas involving forests is ‘low-hanging fruit’.

The need to use site-specific science is more critical than ever, but BOTH extremes want to disregard those ideas, in favor of political desires not supported by science, or even ‘common sense’.

Of course Larry is spot on with his assessment. Jim Furnish always speaks against managing the forests, so his opinion is no surprise.

One change far greater than anything the climate is giving us is the exponential expansion of we humans into the forested environment. Pulling vast quantities of water, paving over wetlands and grasslands, tearing down timber stands for new subdivisions, etc. Reckon that may be having an impact? We put a commercial thinning up near Greer, adjacent to Wink Criglers X-Diamond ranch. Her family homesteaders that land and had pictures of that commercial thinning actually being used as rangeland – nary a tree in sight! Incursion of ponderosa pine is a big problem in the West.

As for the Jasper fire, I’ll let my buddy “Dave Mertz” speak to that. I can tell you, thinning done through White Mountain Stewardship on the Apache-Sitgreaves did absolutely save the towns of Greer, Alpine and Nutrioso in Arizona. However, Wallow was only six times the size of Jasper, so things may be different.

I know of several papers done on Wallow, and the San Juan fires that proved the effectiveness of that cultural work, and saw it for myself, as it was happening! I saw the “hands off” approach to the Escudilla Wildeness provide a pyrocumulus spectacle that absolutely incinerated the entire Wilderness.

We know the results of doing nothing, surely we are smart enough to learn from our successes…… and mistakes.

Jim Z: “Jim Furnish always speaks against managing the forests, so his opinion is no surprise.”

I say “Not so fast, Grasshoppa…”

I actually speak FOR managing forests, and anyone familiar with my record as Forest Supervisor on Siuslaw NF (1992-1999), post NSO crisis would know that. Furthermore Siuslaw NF has had no appeals/lawsuits for over 25 years, while consistently producing some of the highest annual commercial timber volumes in PNW. I know of no other NF – not one – that can make such a claim. I DO recommend managing differently than has been FS practice for decades. So yes, I strongly oppose CC’ing OG on Tongass NF, and huge overstory removals on Black Hills NF, for example. But, I’m quick to laud sensible, “working with nature” practices.

So grateful for this even-handed presentation by you Jim, especially the part about fact vs. opinion, as well as all the references.

Trees take a really long time to grow big enough to harvest so the opinions of how to manage trees tends to carry more weight than the actual facts because the person responsible for replanting the forest is almost never held accountable for the losses/unsustainable consequences when that forest is ready to harvest. At the root of this debacle is the fact that in growing crops there’s usually an annual yield that determines if your farming opinions are based on facts. If your opinions don’t line up with the facts you fail to pay your bills and lose your farm quickly.

But it’s the opposite of that in forestry. On forestlands, you can BS your way through a whole career and even into retirement and never be held accountable for regeneration failure. That’s what the crazies like like Jim Z and Larry Foto do in pretending that their overly-dramatic sweeping overgeneralizations matter more than the facts.

And if all else fails they resort to the toddler-like temper tantrum trips of “you don’t want to do anything for the forest but ignore it,” which is the same argument the British empire used about conquering India and North America. They pretended like only they had the ability to create benefits and no one else did and if we stopped their plunder, it will all go to waste and nothing will get done and we’ll return to the stone age.

But truth is not only is the British empire a faint shadow of its former self, the tree nurseries sales number are making it clear that we’re no longer going to be growing highly flammable tree farms like we used to because fire severity has gone off the charts with for example 1 in every 4 acres of forest in California (1 in 8 acres of all veg. types) has already burned in less than 2 decades.

The future of forestry is no longer about growing flammable mono-crops, but in creating a new era of re-growing/cultivating alternative forest resources in burned over landscape and we have a lot to learn and develop because much like India and America after we drove the British out we have to create something brand new because tree farmers are no longer going to invest in the high risk of growing trees for 40-60 years without fire mortality making them broke because there’s too many fires to guarantee a return on investment now and long into the future.

What we’re going to regrow in the smoking ruins of industrial forestry is going to be amazing in a century or two. There will be all kinds of harvesting of resources rather than just lumber liquidation at an unsustainable rate. The future has never looked more bright for alternative forest resources / wildcrafting cultivations, especially if we get funding to restore landscapes using the Miyawaki method: https://daily.jstor.org/the-miyawaki-method-a-better-way-to-build-forests. But we’ve barely even begun, so it’s easy to pretend nothing is going to get done.

Hi Jim, the Jasper Fire does stand out as a fire that had been largely thinned (80 BA) and this thinning did little to mitigate fire behavior. There are other examples of this in the Black Hills and certainly other Forests. The question is, why was it such a failure? Does it simply come down to fire conditions at the time? Most likely, under moderate fire conditions, it would have fared pretty well.

I remember seeing a study after the Wallow Fire which evaluated treatments around Alpine (I hope my memory is right here) and it showed pretty well that thinning was somewhat successful in providing mitigation and that thinning with Rx burning was the most effective. Now, I know that the Wallow Fire burned under some extreme conditions and I also think the Pondo forest of N. Arizona is not that different from the Black Hills. Why the difference? I really wish that someone or some entity that is seen as unbiased, could do a large-scale study on these questions and come up with some meaningful answers.

I think it is certainly clear that 120+ years ago, there were far fewer trees across a lot of the Western landscape (due to fire and bugs) and stand replacement fire was much more rare. Of course, managing stands for 40 BA does not maximize per acre growth, and some folks don’t like that either.

Were the thinned stands prescribed burned afterward? Thinning without Rx burning often leads to worsening conditions. If not, that fire is a poor example. On many forests, <25% of thinned stands are Rx burned afterward.

I agree that it certainly could have helped. I believe that very little prescribed burning went on within the fire area. The Black Hills NF does not do that much prescribed burning (2,000-3,000 acres/year) and hasn’t for decades.

After a century of fire suppression, a decades-long moratorium on prescribed burns, a lack of environmental litigators and GOP retrenchment the Black Hills National Forest and surrounding grasslands remain at risk to more blazes like the Jasper and Legion Lake Fires. But according to one wildfire boss it’s far cheaper to fight wildfires than to burn prescriptively.

https://www.sdnewswatch.org/stories/custer-fire-how-much-did-the-fight-cost/

Thinning without the follow on Rx burning all too often leads to a worsened next instance of fire.

Thanks for pointing that out Paul! Just putting space between trees is not enough. To say that a treatment failed when there was not an adequate fuels reduction component is not fair!

How refreshing to read this, thank you very much for these excellent points. The scientific evidence is quite clear that windy hot dry conditions overwhelm fuels treatments, making them ineffective during extreme fire weather which ends up burning the vast majority of acreage in forests fires. We need a new paradigm that focuses on real solutions rather than the same tired old logging proposals, which only worsen fire. I also very much appreciate your first point about forest fires restoring forests and enhancing biodiversity. This is true of the hottest, most severe fires. I urge readers to check out the great variety of scientific literature about the wildlife and plants that thrive in post-fire forests, and are harmed by post-fire logging. Many native organisms virtually require severe fire to survive, which strongly indicates that this type of fire is natural and important and always has been throughout the evolutionary history of western forests (and eastern forests too). So much of the media ignores this important point (I am a wildlife biologist so this issue is close to my heart). Also the size of fires now is increasing, but still nowhere near the amount of fire in certain pre-historical times, especially during the Medieval Climatic Anomaly. The best thing we can do is focus on hardening homes and ensuring safe evacuation routes if necessary. Such preparedness will save human lives while still preserving important and natural forest processes such as fire.

Sooooo, you’re just fine with the MASSIVE losses of old growth nesting habitats for owls and goshawks? (because that is what is currently happening)

There aren’t many species of trees that can survive today’s intense firestorms. Even giant sequoias and knobcone pines aren’t reproducing, because their cones were ‘vaporized’. And, seriously, do we want ultra-flammable forests replacing stands that could survive wildfires, with a little help?

Again (ad nauseum), we should not be confusing private logging practices with modern Forest Service projects. It’s is not a valid comparison. Stop pretending it is.

“The scientific evidence is quite clear that windy hot dry conditions overwhelm fuels treatments….”

Yes, but the vast majority of fires do not become large and uncontrollable fire storms. Fuels treatments are crucial to reducing the extent, intensity, and severity of those relatively small fires, so they are easier to contain and control.

AND, with fires generating their own weather, those conditions cannot be used to illustrate anything. If you want to judge the weather’s effects on wildfires, you MUST use the weather OUTSIDE of the wildfire perimeter.

Along with that idea, conditions in the mountains are very often very dry and hot, with variable winds. Another ‘semi-constant’ which has consistent effects on wildfires. Of course, actual wind events do overcome fuels projects. They also overcome overstocked “pristine” forests with huge fuel loading.

The scientific evidence does not say that windy hot dry conditions overwhelm fuels treatments, making them ineffective during extreme fire weather. Please read the in-depth review of that literature led by Dr Susan Prichard at UW here: https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2433

“Weather changes douse big fires, people do not.”

This phrase caught my eye because it sparked a memory of my Forest Entomology professor (mid-1980s) saying the same thing about insect epidemics – humans have rarely if ever altered the path of an insect epidemic.

While the loss of natural resources can be contrary to our values, those values are just that – human. Our society has struggled with what is “right” and “wrong” in forested landscapes when much of what happens in the natural world just “is”. Jim’s commentary, and the response commentaries here, reflect that no one solution works everywhere. So, here is what I believe: we need to be open-minded to other possibilities/perspectives while ALSO recognizing that sometimes there is not a damn thing we humans can do to alter wildfire dynamics.

Furnish is NOT saying – allow fires to just happen – he’s saying what we are doing is NOT working because the climate is now driving large fires and is overriding on the ground efforts. Until we address that reality, it’s akin to Sisyphus pushing a boulder up hill as noted here -https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320722000520. Also, Jones et al. is a commentary – much of what they present is cherry picked science to support their views while they completely avoid criticisms of their cited studies. This is far from settled in the scientific community and cutting off debate is akin to confirmation bias.

How can you say that when fire suppression folks are actually out there right now… using tools to stop fires from going where we don’t want them to go. Which works most of the time. So are you talking about certain fires?

The Mosquito Fire is burning in unmanaged lands, with very little abnormal winds on it. The column of smoke was so straight and tall that it could be seen from downtown San Francisco. Much of the terrain is steep and brushy canyons. And, yes, they do seem to be using managed forest to successfully accomplish ‘black’ firelines.

It seems like ‘you people’ are just complaining about the Congressional decisions to do more forest management than has been done in the past. Perhaps you should write your Congress-folk? Since potential lawsuits are likely to fail, it seems like all you are really trying to ‘preserve’ is the controversy, at this point. You people are just one of many ‘charlatans’ out there, vying for diminishing eco-donations.

I am all for smart climate actions, but do not pretend that such actions will ‘save’ any of our current at-risk forests in the western US.

With all due respect to the article….we have a “epidemic of trees” on our public lands. Bio-mass burns and it is driving the destructive wildfires that we are seeing on the landscape since 1988.

I don’t think most people, even most foresters understand how dramatically the dry forest types in the west have changed in recent decades.

In 1994, the Wenatchee National Forest experienced the Tyee Fire. Our first 100,000 acre fire. I had just writing completed a draft paper with the Forestry Sciences Lab, and others that predicted that we would lose our Spotted Owls due to fire. We had 50 pairs of owls in Chelan County at that time, we lost 14 pairs in the Tyee Fire. Today, we have ONE owl left in Chelan County. Granted the Barred Owl was also a factor.

When I came back to the office in November of that year I decided to see just how much bio-mass the Wenatchee National Forest was growing each year. Including Wilderness and other no-cut allocations the solution showed that the forest was growing 500 million board feet a year. Our harvest level under the Clinton Forest Plan was 25 million. For a forest that has historically had fire on the landscape, that growth was “removed” in stand replacement fires that were impossible to control.

At that same time I found the cruise plots from the state of Washington sections 16 and 36 pending transfer to state management. It was eye-opening to see the very light stocking that existed on the landscape in the early 1900’s.

The landscapes we accept as “normal” stocking today are grossly overstocked. Foresters still refuse to give up their German heritage and look at full stocking as normal and desirable. I suspect the stocking on Jasper Fire did reflect “intensively managed Ponderosa Pine forest”.

It is simple, remove the bio-mass and the fire intensity goes down significantly. Keep on our present path and we are rapidly converting are National Forests to National Brush Fields.

Worse yet, on many areas the high intensity fires are destroying basic soil productivity. It will centuries before those areas of the National Forests will have trees growing on them.

The problem is much, much worse than we can even imagine. With all due respect, we cannot log our way out of this, nor can we continue on the present path. We have lost hundreds of lives, thousands of homes, and endangered the health of the American people with wildfire smoke, the consequences of which will not be totally known for decades.

We can save our communities, we can save our forests from becoming brushfields, and we can save the public health. BUT that will take planning and more importantly money and the will to protect our forests and other wildlands.

I disagree with Furnish. Reducing bio-mass works, but it is a big job.

I was on the Tyee Cr. Fire. I was a Crew Boss of a 20-person crew. We were on the fire on day 2. I got to work on a number of Divisions and saw a lot of the fire. It has been a long time, but my memory is that there seemed to be a considerable amount of active management in the area at that time. I don’t remember any big ah ha moments, where I saw the management made a big difference (unlike some other places I have been over the years, on fires). There was some pretty impressive fire behavior, it was hot and dry that summer. Am I wrong? Were there big differences between active management areas and untreated areas? Did anyone look at that?

I was there from day 1 as the PIO on the initial team. I do remember we had ONE twenty person crew for the first two days or so. Were you that crew?

We ended up working THREE 14 day shifts on the fire. I believe that was the first time that had ever happened in the Forest Service.

Lots of interesting things came out of Tyee. The Wenatchee has already shifted gears to its Dry Site Strategy a couple of years earlier. Pretty much the entire Forest was working on reducing the large wildfire threat to communities for over two years when Tyee broke out. There was a fire two weeks earlier in Tommy Creek that the Forest staffed heavily.

I was writing a paper with the Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Lab on why Spotted Owls on the Wenatchee were NOT sustainable given our fire history.

BUT, getting back Tyee and ah ha moments. There were quite a few.

I was working at the Cache and dispatch center that night when a thunder cell decided to drop about 2000 strikes on forest. I saw the GIS plot at 2:00 am when I was told that our team was meeting at the Entiat Fire Hall at 6:00 am that morning to take over management of the fire.

Out of 2000 strikes the Forest picked THREE fires to manage with teams. We lost all three fires, kept ONE to 2000 acres so technically did not lose that one. The other 1,997 strikes went nowhere. That was a ah ha moment and a scary one at that. You pick the right fires to staff and still lose them.

The Forest and it was a local team quickly made the decision that if it got into Shamel Creek that it would not be staffed in that drainage. Shamel Creek had advanced reproduction, combined with standing snag, and criss-crossed down timber. When it got into Shamel Creek the fire blew up.

That column and fire storm was quite impressive. If you remember that night the fire made a 13 mile run in the middle of the night. That was a “holy crap” moment. Nobody expected it to do that. I had wrote into my paper that the Wenatchee fire folks were quite confident that they could hold any fire in the Entiat to 50,000 acres….oops.

When the column collapsed all sorts of interesting things happened. My recollection and I am not a fire person, is that the problem with fire spread wasn’t related to high winds, but the column collapse. On the Wenatchee the high winds were always a concern, but the real fear was when the columns collapse.

The IC described the column collapse as a blow-torch moving across the landscape. In Mud and Potato Creek there were Ponderosa Pine trees burned that were quite a distance from other trees. I personally wonder, when folks talk about high winds, were they winds or was it a column collapse??

The forest did have treated areas and untreated areas. The treated areas came out pretty well even with the column collapse.

I remember sitting with plans at 2:00 am looking at a map. That night every town in Chelan County was under evacuation orders. The Plans Chief said that it looked like all the fires might meet in Section 19!! The team was the first joint Forest Service and DNR team in the state and that paid dividends as the fire grew and more and more help arrived from other agencies and DOD. Love those Marines, they come totally self-contained.

Timonthy Egan of the New York Times did a front page article in late August, 1994 on the treatments the Forest and private land owners had made prior to Tyee. It would be worth to find that article and take a look at it with todays eyes.

We set up the tour for him and he wanted me to lead the trip for him, but I have a very bad personal history with the New York Times and decided to assign a PIO to Egan. It was a well written article if I remember correctly, but I had little time to read it. Probably worth finding the article if you have a library with the New York Times in the archives. It would give you a perspective on what the Forest was doing at the time of the Tyee fire.

The Forest did hire a photographer to document the fire. In the middle of the fire, the Forest hired John Marshall to establish and photograph photo points throughout the fire area. I believe the photo’s were redone at 10 and 20 years. I think John owns the photo rights, don’t ask how that happened.

Lots of “good” things came out of Tyee. When it came to fire management the Wenatchee was pretty confident with their abilities. With Tyee, the Forest made significant moves to improve their abilities. Which turned out to be very helpful in future fires.

Well, my memory is a little fuzzy but I am thinking that we got there in the evening that a Team got assigned. We had a briefing at a park in Entiat. The next morning we went on a road west of Entiat and started prepping homes. I believe it was out near the fish hatchery? Then the fire came over the ridge to the west and spot fires popped up all over the place. We ran around like crazy, putting out spot fires. Then we moved down the road to the FS work center at dark, and burned off all around the work center. It was one of my more exciting days working on fires. We got to see a lot of action on that fire.

Vladimir Steblina- I see my name mentioned with respect to photography I did of forest burned in the Tyee fire of 1994. I retook some of those photographs this spring, and am looking toward 2024 as the thirtieth year after the fire. Interest and support from the Forest Service over the years has been inconsistent. The Forestry Sciences Lab did fund twentieth year re-takes. I have replicated photography at many sites on my own over the years, and those photographs I own outright. The Forest Service is free to do anything they want with the rest. I have used the sequences of vegetation going back in a couple of museum exhibits, lectures, and an educational DVD.

Thanks for the info.

So the original photos are still in government ownership? Are they are the forestry sciences lab in Wenatchee. I would be interested in revisiting some of the plots, particularly those where the fire burned hot. I am curious about the impact on soils.

I understand about the issue of ownership of photos. I took some great air tanker pictures from my driveway, but when people saw fire pictures and my name they assumed they were in the public domain. The best fire pictures I took were as a civilian!!!

A right click on Google Chrome gets a drop down menu for “check the internet for similar photo’s”. That gives you exact copies of photographs and websites that “borrow” without permission.

For a while there, I just sent bills to people using my photos. Government agencies pay the best, they know the laws and still “borrow” photos!!

Vladimir- Lets continue the conversation outside of the forum. My e-mail address is [email protected]

The Wenatchee lost most NSO due to logging their habitat for decades. State lands have butchered NSO habitat, not to mention private lands. Cumulatively there was little habitat left. The little left was burned by the Tyee fire. To blame loss of NSO on fire is simply a falsehood.

That is NOT true.

I was there. I worked on the Spotted Owl issue on almost a daily basis until I took the Recreation and Wilderness job in 1997.

I only have a hard copy of my Spotted Owl paper otherwise I would send you a copy.

Tyee was the start of the decline of Spotted Owl habitat on the Wenatchee. I-90 played a interesting role.

Both northern California and the Wenatchee had high spotted owl populations with high reproductive success. They are had high mortality of young, probably due to the fact that most of the territory was already occupied.

A very large portion of the owls on the Wenatchee, were in second and third growth stands.

I do admit to losing all interest in Spotted Owls once I took the Recreation job.

I would find this commentary quite humorous if it weren’t written with sincerity. You provide no counterpoints to the listed examples of misinformation in wildfire science. Instead, you just repeat those examples of misinformation without any scientific basis except for anecdote examples and half-truths which the authors specifically call attention to in their paper (https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fee.2553).

I refer you to voluminous list of citations…

Which of those citations provide substantive criticisms of the 5 examples of misinformation the authors lay out in Supplemental Table 1 (https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/downloadSupplement?doi=10.1002%2Ffee.2553&file=FEE2553-sup-0002-Table_1.pdf)

Schoenagel et al

Mitchell et al

Abatzgolou et al

Evers et al

And many more

And how do those citations provide substantive criticisms of the 5 examples of misinformation that the authors lay out in Supplemental Table 1? It is pretty funny reading through the comments – did folks actually read the paper?

Hey Patrick – If you are hesitant to read the entire papers, perhaps just read the conclusions of all the cited papers. A quick scan will reveal many of the answers you are seeking. The papers themselves contains the conclusions, findings, and links to supporting information. For example, here is a link to a 2022 synthesis, which was published in a peer reviewed science journal, which has a number of the citations listed below Jim Furnish’s Response.

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/11/5/721/pdf

+++++++++++++++++

2.3. Thinning to Reduce Fire Risk or Severity and Carbon Loss

2.3.1. Broad-Scale Thinning to Reduce Fire Severity Conflicts with Climate Goals

A reaction to the recent increase in the intensity and frequency of wildfires is to thin forests to reduce the quantity of combustible materials. However, the amount of carbon removed by thinning is much larger than the amount that might be saved from being burned in a fire, and far more area is harvested than would actually burn [42,46–49]. Most analyses of mid- to long-term thinning impacts on forest structure and carbon storage show there is a multi-decadal biomass carbon deficit following moderate to heavy thinning [50].

For example, thinning in a young ponderosa pine plantation showed that removal of 40% of the tree biomass would release about 60% of the carbon over the next 30 years [51]. Regional patchworks of intensive forest management have increased fire severity in adjacent

forests [49]. Management actions can create more surface fuels. Broad-scale thinning (e.g., ecoregions, regions) to reduce fire risk or severity [52] results in more carbon emissions than fire, and creates a long-term carbon deficit that undermines climate goals.

As to the effectiveness and likelihood that thinning might have an impact on fire behavior, the area thinned at broad scales to reduce fuels has been found to have little relationship to area burned, which is mostly driven by wind, drought, and warming. A multi-year study of forest treatments such as thinning and prescribed fire across the

western U.S. showed that about 1% of U.S. Forest Service treatments experience wildfire each year [53]. The potential effectiveness of treatments lasts only 10–20 years, diminishing annually [53]. Thus, the preemptive actions to reduce fire risk or severity across regions have been largely ineffective. Effective risk reduction solutions need to be tailored to the specific conditions. In fire-prone dry forests, careful removal of fuel ladders such as saplings and leaving the large

fire-resistant trees in the forest may be sufficient and would have lower carbon consequences than broad-scale thinning [54]. The goals of restoring ecosystem processes and/or reducing risk in fire-prone regions can be met by removing small trees and underburning to reduce surface fuels, not by removal of larger trees, which is sometimes done to offset the cost of the thinning. With continued warming and the need to adapt to wildfire, thinning may restore

more frequent low-severity fire in some dry forests, but could jeopardize regeneration and trigger a regime change to non-forest ecosystems [53]. While moderate to high severity fire can kill trees, most of the carbon remains in the forest as dead wood that will take decades to centuries to decompose. Less than 10% of ecosystem carbon enters the atmosphere as carbon dioxide in PNW forest fires [21,46]. Recent field studies of combustion rates in California’s large megafires show that carbon emissions were very low at the landscape-level (0.6 to 1.8%) because larger trees with low combustion rates were the majority of biomass, and high severity fire patches were less than half of the burn area [55,56]. These findings are consistent with field studies on Oregon’s East Cascades wildfires and the large Biscuit Fire in southern Oregon [57,58].

To summarize, harvest-related emissions from thinning are much higher than potential reduction in fire emissions. In west coast states, overall harvest-related emissions were about 5 times fire emissions, and California’s fire emissions were a few percent of its fossil fuel emissions [59]. In the conterminous 48 states, harvest-related emissions are 7.5 times those from all natural causes [60]. It is understandable that the public wants action to reduce wildfire threats, but false solutions that make the problem worse and increase global

warming are counterproductive.

42. Hudiburg, T.W.; Law, B.E.; Wirth, C.; Luyssaert, S. Regional carbon dioxide implications of forest bioenergy production. Nat.

Clim. Change 2011, 1, 419–423. [CrossRef]

43. Schlesinger, W.H. Are wood pellets a green fuel? Science 2018, 359, 1328–1329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

44. Körner, C. Slow in, Rapid out–Carbon Flux Studies and Kyoto Targets. Science 2003, 300, 1242–1243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

45. Solomon, S.; Plattner, G.-K.; Knutti, R.; Friedlingstein, P. Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1704–1709. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

46. Campbell, J.L.; Harmon, M.E.; Mitchell, S.R. Can fuel-reduction treatments really increase forest carbon storage in the western US

by reducing future fire emissions? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 83–90. [CrossRef]

47. Mitchell, S.R.; Harmon, M.E.; O’Connel, K.E.B. Forest fuel reduction alters fire severity and long-term carbon storage in three

Pacific Northwest ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 643–655. [CrossRef]

48. Rhodes, J.J.; Baker, W.L. Fire probability, fuel treatment effectiveness and ecological tradeoffs in western US public forests. Open

For. Sci. J. 2008, 1, 1–7.

49. Hudiburg, T.W.; Luyssaert, S.; Thornton, P.E.; Law, B.E. Interactive Effects of Environmental Change and Management Strategies

on Regional Forest Carbon Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13132–13140. [CrossRef]

50. Zhou, D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, S.; Oeding, J. A meta-analysis on the impacts of partial cutting on forest structure and carbon storage.

Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 3691–3703. [CrossRef]

51. Stenzel, J.; Berardi, D.; Walsh, E.; Hudiburg, T. Restoration Thinning in a Drought-Prone Idaho Forest Creates a Persistent Carbon

Deficit. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2021, 126, e2020JG005815. [CrossRef]

52. Zald, H.S.; Dunn, C.J. Severe fire weather and intensive forest management increase fire severity in a multi-ownership landscape.

Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1068–1080. [CrossRef]

53. Schoennagel, T.; Balch, J.K.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Dennison, P.E.; Harvey, B.J.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Mietkiewicz, N.; Morgan, P.;

Moritz, M.A.; Rasker, R.; et al. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

USA 2017, 114, 4582–4590. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

54. Hurteau, M.D.; North, M.P.; Koch, G.W.; Hungate, B.A. Opinion: Managing for disturbance stabilizes forest carbon. Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10193–10195. [CrossRef] [PubMed]55. Stenzel, J.E.; Bartowitz, K.J.; Hartman, M.D.; Lutz, J.A.; Kolden, C.A.; Smith, A.M.S.; Law, B.E.; Swanson, M.E.; Larson, A.J.;

Parton, W.J.; et al. Fixing a snag in carbon emissions estimates from wildfires. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3985–3994. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

56. Harmon, M.E.; Hanson, C.T.; DellaSala, D.A. Combustion of Aboveground Wood from Live Trees in Megafires, CA, USA. Forests

2022, 13, 391. [CrossRef]

57. Meigs, G.; Donato, D.; Campbell, J.; Martin, J.; Law, B. Forest fire impacts on carbon uptake, storage, and emission: The role of

burn severity in the Eastern Cascades, Oregon. Ecosystems 2009, 12, 1246–1267. [CrossRef]

58. Campbell, J.; Donato, D.; Azuma, D.; Law, B. Pyrogenic carbon emission from a large wildfire in Oregon, United States. J. Geophys.

Res. Biogeosciences 2007, 112, G04014. [CrossRef]

59. Bartowitz, K.J.; Walsh, E.S.; Stenzel, J.E.; Kolden, C.A.; Hudiburg, T.W. Forest carbon emission sources arenot equal: Putting fire,

harvest, and fossil fuel emissions in context. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 867112. [CrossRef]

60. Harris, N.L.; Hagen, S.C.; Saatchi, S.S.; Pearson, T.R.H.; Woodall, C.W.; Domke, G.M.; Braswell, B.H.; Walters, B.F.; Brown, S.;

Salas, W.; et al. Attribution of net carbon change by disturbance type across forest lands of the conterminous United States.

Carbon Balance Manag. 2016, 11, 24. [CrossRef]

How does that paper in anyway address the pre-bunked misinformation items listed in supplemental table 1 from the Jones et al paper? I am going on a big stretch here and say that it doesn’t. I have not read a single counter point in the comments so far that makes any arguments against the base elements listed in the original commentary paper.

What about the ecological resilience gained through “thinning from below”? Anti-thinning folks won’t touch that issue (as seen in the here and now of this posting).

What about burned human infrastructure, including bridges, roads, canals, power lines, campgrounds, interpretive sites and more?

I think the decisions have been made, via Congress. Will there be lawsuits from the ‘usual suspects’? I’m sure they will try.

Now tell us how to deal with land disposition and disbursement patterns, and how the Justice Department and IRS will deny the Federal/Private interface land ownerships any right to use their land. That fits the socialist pattern we saw from Region One advice for western Montana and checkerboard railroad land grant and USFS ownership answers to fire and occupied homes. If I remember, it was a 30 mile NO OCCUPATION private land buffer between USFS land and homes. Private land to give up a 5 township wide buffer to protect the Federal lands.

The fact that we must live with is the USFS is NOT a dependable source of anything. It is a fiefdom. A political pawn. It is governed by the Executive and executive appointments that are approved by the Senate. It now regulates forest use by limiting how many can hike on their primarily unmaintained trails each day, week and year. Internet frenzy for an hour each year to get a permit to camp in a wilderness. USFS is now not important in our economy except as forever employment and a threat to private land and assets. Worse, the citizen cannot gain tort claims against the sovereign.

Fire policy is a threat and the citizenry has no recourse when damaged by poorly exercised authority. But let a Federal tree limb land on a power line, and PG&E is liable for deaths and damage, to the tune of $32 Billion dollars. One of the litigants is the Federal Government trying to get their pound of flesh from the quasi public private public utility. How much of that can America afford? Federal fire from power lines that are required by Federal and State law, now in insanely narrow rights of way overgrown by trees not there a century ago when lines were placed to serve rural residents. Energized power lines are vulnerable to wind thrown trees and limbs, and always the public utility is the ONLY pockets deep enough to sue. Never the sovereign. So pontificating from the safety of the protections of English law, on sidelines with full security from liability, ever, is meaningless. Civil Service full protection to screw up and never have to suffer consequences is a fantasy world. Be sure to use the correct pronouns.

The real deal is that no Federal timber of any amount that is meaningful to build affordable housing. The hundreds of millions of acres of Federal land unavailable to provide affordable housing is criminal and against all principles of public interest. Biden wanting to leave office having 30% of the Nation in Federal hands is a threat to our democracy and no way to site affordable housing in gerrymandered zoning regulations made by citizen pawns of elected leadership. The super majority needs to look in the mirror, and see what the forces of societal suppression actually look like.

The USFS land will catch fire, and the most vulnerable to fire destruction is the 10-50 year old private stand of timber. You thin it or don’t thin it, and it is totally incinerated. From Blue River to Leaburg. From Detroit to Sublimity. Green Diamond was diligently managing its holdings in Lake county, and all the post Weyerhaeuser planted trees burned totally in all stages of admired management. What didn’t burn totally were trees over 100 feet high. Any and all under 60 feet tall are black sticks, almost limbless. 50 to the acre or 500. Lots of green grass under them today. Wet spring and only a few thunder storm hundredths of an inch since. No cows.

Lots of fine fuels for next year. But no trees left to burn. Half million acres and more.

Ice and rocks at Cascade summit. Go west and it is almost now all Wilderness until you get to 4000 feet and lower. Wilderness is the fire source annually. It burns into roadless and patch clear cuts now with 30 years of regrowth and not a new clear cut to be seen. ENGOs are pyromaniacs. Sue and settle has brought no good. I was happy to see Warner creek area burn in Cedar fire this month. Karma. President Clinton paid the purchaser of the Warner Salvage sale to give it back to USFS. With Federal money. In August of 1996. Big Green win late in re-election campaign. Furnish needs to tell you how that went down, its cost, and how Bill Clinton made an ass, again, of the USDA-USFS.

West of Federal, USFS land, and you are in industrial forests, clear cut at annual mean increment of growth. 35 to 50 years. With luck, capture returns on investment and then face proposed punishing taxation. More homeless who have given up chasing every increasing costs of government and no equal return in opportunity.

ALL the private industrial timberlands are at risk each year. Just like salmon. Fire from the Fed’s land is the predator on private industrial timberlands. Thin it and you have the needed 30% green top and that flammable hot fuel has replaced, by design, the 10% or less green tops in stands with no cutting and removal of trees in order to maximize light and water to the “leave” trees. Both burn equally in crown fires. Equal fuel. Far fewer trees with four times as many needles.

Chinook salmon are being consumed at sea by Marine Mammal Act totally protected seals, sea lions, orcas. Resident orcas (three types of north Pacific orcas: resident which eat chinook salmon and lightly on mature chum salmon, second largest of salmons. Transient orcas who predate primarily marine mammals, from whales, to whale calves, to seals, sea lions, sea otters, dolphins, porpoises. Off Shore orcas, who predate sharks. Very little observation and reporting. Now have been videoed killing Great White Sharks, off SF Bay, consuming only their very large liver. Neatly excised. To the point that when orcas show up and predation happens, the annual convocation of GWS to predate elephant seal females who leave the rookeries to feed to be able to continue nursing pups, suddenly ends and no GWS are seen for another year or more.

Resident orcas pursue and eat the largest chinook. Chinook become larger by staying at sea for more years. Each year they are larger the more likely to be killed by an orca in NE and SE Alaska. Hence, today’s troll caught AK chinook is half the size it was 30 years ago. Apex predator causing chinook losses at sea, to the point research indicates a 15% annual loss of returning adults from their parent class. To the point that CA has great hatchery returns of Chinook that now are three and some four year old females, and 2 and three year old males. Natural selection and some what impacted by troll retention minimum lengths of 26″ and 28″, depending on whether off CA coast or Oregon coast where 28″ is legal and 27″ is a $500 fine for one fish. Or more, depending on which Oregon court you end up in. Selecting to save small chinook is resulting in more survival of small hatchery chinook. Nobody has reported if that is true at government hatcheries elsewhere.

Salmon doomed by an act of congress to protect predators, and private timber by an act of congress to “protect” Wilderness. Which Wilderness in Oregon has NOT burned since 1986? What was Opal Creek Wilderness’s actual life as “untrammeled by the hand of man” with a village of special environmental activists and activism within its boundaries. 30 years?

Fire today is primarily about who owns what and how they are protected or not protected. It is about geography, local weather and geology. It is hesitant managers. Missing policy. Misinformation from many sources, some official and government produced. Others from “non profits” words to raise money to pay handsome salaries. Reality in Oregon, where over 60% of the State is Federal land, is 20% of the timberland produces 80% of the timber. And is the most vulnerable to loss to fire before reaching market size. j Federal, State, other government, and private timberlands, and the industrial sustainable, under 50 year rotation clear cutting, Is making the lumber. And that is a very few high production mills carrying most of the load. Timber Barons, as it were. It appears to me it is also the most at risk to be consumed by fire, just like chinook are to marine mammals.

All of this is the result of land use patterns and US Govt land disbursement and disposal. Now the Wilderness Act has had its logical impacts predicted in opposition to wilderness in the 1960s. French Pete. Remember it well. And that had the Rebel fire, I believe, a decade ago.

Geography, geology, Federal land use policies over a century and a half, and this is what we have. Now the US Govt will create more problems with failed socialist solutions aimed at private initiative. And the fire will never end. The orcas will eliminate chinook as “kings” of salmon. Small is better able to survive. Isn’t that the “island theory” of passerine bird size? And pygmy mammoths on Siberian sea islands? Geography will save islands of trees from wilderness fire. And do it better than Congressional protections made with votes, not tree survival, as the driver.

I made it almost all the way through this screed, until I came to a question I could actually answer: “Which Wilderness in Oregon has NOT burned since 1986?” Devil’s Staircase Wilderness! 😉

When something contradicts one thing you know something about, you tend to not bother to pay much attention to the rest of it. “Biden wanting to leave office having 30% of the Nation in Federal hands” is of course not true. (Nor are any obviously uninformed cries of “socialism.”)

Jim Furnish is mixing up, challenging the conventional wisdom, and that’s a good thing. Timber management, in particular commercial thinning, is presented by many to be the solution to today’s problems in forest management. Specifically, to the problems with wildland fire. There are problems with that solution and Jim brings up several of them.

Number one, how effective is it in addressing our wildland fire situation? There are those that say it is the solution, we just need to do a whole lot more of it. Others say, like Furnish’s example of the Jasper Fire (he is right by the way, the Jasper Fire area had been extensively thinned for years and now most of it is a prairie, 20 years later) that it is far from a cure all.

Of course, the timber industry says, “we are your solution, just let us do it”. There is certainly some degree of self-interest here. I recently visited a fire from this summer. It had had recent commercial thinning combined with non-commercial thinning within some parts of the fire area. Now, some of those areas, where I think most people would agree the FS did everything right, are now proposed for salvage as most of the trees will not survive.

Thinning in and of itself, can certainly be beneficial. If you are worried about climate change, having fewer trees on the landscape creates less demand for water, and should help stands better survive climate change impacts. This is regardless of what it does for fire mitigation.

I think the answer of what type of forest management, treatment types, in what areas, needs to be determined to the best that it can be. USFS Research should be making it job one, to go out and visit a lot of wildfires, armed with timber management info from the local unit, and see what worked and what didn’t. There are plenty of examples to research, just go do it! Otherwise, these arguments will go on ad infinitum.

What we have been doing, hasn’t gone so great, certainly not to scale anyway. Maybe it’s time to look at the problem differently.

Thank you, Sharon, for posting this commentary. We need to have all “sides” of the issue considered respectfully to get anywhere. The issues are so complex.

Right now, the Jones et al commentary is being used in the Santa Fe area as an attempt to essentially shut down discussion. Articles, letters to the editor and newsletters are pointing to the commentary as a reason that no science, and no conservation organization or public perspective outside of the science and viewpoint approved of and utilized by the Forest Service and their collaborating agencies is valid, or should even be a part of the discussion. It’s just “misinformation.” This is simply wrong and shuts down all potential for arriving at real solutions.

I do think Steve Wilent’s comment “Yes, but the vast majority of fires do not become large and uncontrollable fire storms. Fuels treatments are crucial to reducing the extent, intensity, and severity of those relatively small fires, so they are easier to contain and control” has some validity. But the amount of times this is true are decreasing. The weather-drive fires we have been having are much less responsive to fuel treatments.

Consideration of whatever positive effects fuel treatments out in the forest may have needs to be counterbalanced by consideration of the risks and adverse impacts of the treatments. In New Mexico we just had a 341,000 acre fire that literally destroyed communities, homes, and livelihoods. Three people died in the ongoing post-fire flooding. About 80,000 acres burned at high severity. In the bigger picture, even high severity fire is within the natural range of variability, and may ultimately promote biodiversity, but this is too much for our local forest and communities to reasonably withstand. And it was a direct result of two prescribed burns gone very wrong. Two Forest Service fuel treatments gave us the largest fire in New Mexico history.

A genuine cost/benefit analysis is needed and never has been done. Along with the risks of escaped prescribed burns, the massive ecological damage that fuel treatments have caused to our forests needs to be considered, and the public health impacts of the increasing amounts of prescribed burn smoke in our air.

Yet Jones et al, and those who subscribe to their views want to basically shut down an open scientific discussion, and to silence public input that does not agree with their perspectives and actions. We are not going to be silenced, the issues are much too important.

Recently, the National Prescribed Fire Review was released. Is this an example of how we should trust the Forest Service and associated scientists and experts? It contains one massive contradiction. It states that the USFS intends to greatly increase fuel treatments (up to 4X current levels,) while at the same time acknowledging failures in implementing burns almost across the board. Failures include issues with the Forest Service culture, lack of agency capacity, lack of equipment and contingency resources, and a need to develop and implement better training programs. Also a shortage of personnel, including specialists. I would add to this failure to incorporate a broad range of the best available science in project planning and analysis.

Solving these issues will take much time and resources, if it’s even possible with their current approach, and that’s doubtful. And yet they have given the conditional go-ahead to resume the prescribed burn program now. This is likely to lead to more escaped prescribed burns. Solving the issues will take a new approach to a great extent, not more of the existing approaches. None of this is evident in the National Rx Review.

All peer-reviewed scientific research, input from conservation organizations, and from the public needs to be included in the dialogue, and incorporated into a better national fire policy. It is time for a new paradigm as the old one is absolutely not working any more.

Sarah and others: I’ve said several times here that one peer-reviewed paper by 20 coauthors, based on a meta analysis of numerous papers, is a must-read for anyone interested in wildfire: “Adapting western North American forests to climate change and wildfires: 10 common questions.” Open access:

https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eap.2433

I have got to run and get back to my project to remove invasive avian bird species from the shrub-steppe slopes of south-eastern Washington. Besides which my bird dog is giving the stink eye for wasting time typing on this subject.

But a couple of parting shots.

We are wasting much time and energy debating management of National Forests. It is awful what is going on in the National Forests, but it is even worst in the communities just outside the National Forests where we are losing lives and homes every year.

The focus needs to shift on protecting those communities. On the National Forests and Parks really at this point all we can do is save a few of the unique ecosystems such as the Giant Sequoia’s. Our National Forests and Parks will be unrecognizable is a few short decades. Even return to the mass logging of the 1970’s will not solve the problem.

The issue is that unlike the National Forest and Parks there is no ONE management agency responsible for management of fire risk on the adjacent private lands. In Washington state, even the Department of Natural Resources contracts out the fire fighting for these lands….until a mega-fire visits the landscape. They do have great programs for reducing fire risk in forests. None in the shrub-steppe where Washington’s largest fires have occurred in the past decade.

The second issue is climate change and its effect on forests. The solution, according to the environmental community is for MORE Industrial Wind and Solar areas across the lands. Reverse climate change and save the forests!!

Early in my professional career I did a growth study for a medium sized privately held forest property. I learned two things.

One is that climate does affect forests. I told my boss, that maybe we should do a growth study for a 10 year drought period. That number would be significantly different that for the “wet” 10 years that our growth study was based.

Two, trees grow at amazing rates!! The company told us that our growth and inventory data must be wrong. They had been “liquidating” the property for the last ten years. We pointed out that the VOLUME on the property was EXACTLY the same as the previous inventory ten years previous. They just didn’t have many trees over 24 inches. They had lots of trees in the 12-24 inch age class.

It took them 50 years to finally run out of trees and finally convert the property to subdivisions.

This book should be required reading for every forester.

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520286009/the-west-without-water

It covers the “natural” climate history of California for the last 10,000 years. I suspect that since the last hundred years were abnormally stable and WET in California, that future forest management challenges will be daunting. Great book, needs to be read by every forester.

If anything, this conversation (which some seem to think should be a shouting match) illustrates the key point Furnish is trying to make in his well documented counterpoint:

“…agency “fire dogma” needs to be revisited… we are not close to pulling ourselves through the knothole of now”.

It’s all about looking beyond our own confirmation bias and paying closer attention to what is actually happening on the ground (i.e., commercial “thinning” and other conventional approaches — as practiced — aren’t working). Only then will hearts and minds change, with policies and better outcomes to follow.

Everything else is just smoke.

If anything, this conversation (which some seem to think should be a shouting match) illustrates the key point Furnish is trying to make in his well documented counterpoint:

“…agency “fire dogma” needs to be revisited… we are not close to pulling ourselves through the knothole of now”.

It’s all about looking beyond our own confirmation bias and paying closer attention to what is actually happening on the ground (i.e., commercial “thinning” and other conventional approaches — as practiced — aren’t working). Only then will hearts and minds change, with policies and better outcomes to follow.

Everything else is just smoke.

Additionally, there should be some talk about the No Action alternative of those lands that burned. How would the fire have burned if that land was not thinned? This talk about “commercial “thinning” and other conventional approaches — as practiced — aren’t working” is based on recent projects? It sounds rather anecdotal, to me. For example, the Caldor Fire burned through much ‘managed’ forest, but the whole of the burned acres ‘labeled’ as ‘managed forest destroyed by wildfire’.

In the Sierra Nevada, there should be some examples of some very recent projects that burned. In many cases, such huge pieces of burned lands haven’t been scrutinized, yet. Many large parcels were unmanaged. Private lands were ‘managed’ by clearcut. Fuel loadings were very high. Terrain is problematic for both firefighting and fuels projects. Finally, during a serious drought all forests are at high risk from burning, probably human-caused.

Site-specific conditions are addressed on the stand level. Climate change affects regions. Apples versus oranges, although they are both fruit that grows on trees.

NY Times today: “California’s Largest 2022 Wildfire Puts U.C. Research to the Test” — University of California scientists previously conducted controlled burns on 250 acres where the Mosquito fire recently traveled.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/16/us/california-wildfire-research.html

Subscription

Excerpt:

After crews wrestled the Mosquito fire into submission within Blodgett’s bounds over the weekend, York re-entered the forest on Monday. In areas where he and his colleagues hadn’t used prescribed fire and other methods to thin out the flammable brush, he saw death and devastation everywhere. The fire racing across the ground had been intense enough to ignite the treetops.

“When I look up into the canopy, it’s just completely black, and the crowns are completely charred,” York said.

But the 250 acres or so where prescribed burns had taken place were largely spared the worst, he said. Some large trees were still killed along the edge of this area. But in other spots, he said, the blaze appeared to have moderated quickly.

We all have perceptions, we all have opinions, the ability to rationalize where we go from here is always in play. I remember Char Miller explaining what the greatest good is now, and will it be the same for the future? Same thing here; however, thinning commercially in forest lands is a proven cultural action against wildfires. Region 3 has proven that! Don’t color all work going on within the national forests as good, bad or indifferent. Too much emphasis on western disasters when western successes are also evident. Thinning worked in Arizona’s Wallow; 4- FRI is trying to emulate that success.

Sara is correct on the New Mexico “prescribed fire to wildfire” assessment, this is the biggest self induced black eye on the forest service in generations, and nothing, nor no one is being held responsible for it! Climate change did not influence one bit, the reckless operations leading to that disaster.

Vladimir hits that proverbial nail on the head; there is an epidemic of trees on the landscape, in the western us! Regions 8 and 9 know how to take care of that simply, being east of the 100th Meridian helps.

As for Jim? I read your book. I do tend to oversimplify impression. I do agree more with you than not, and certainly agree that the Black Hills timber program is unsustainable, but my opinion still stands.

Sharon, I think you found a topic that brings out the passion and interest to a wide range of commenters. Good work!!

Jim points out we need to re think our fire policies given their failures during extreme events that are becoming more common. We always need to be open to evaluating our present policies IMO.

My forest management observations of over 60 years began as I was charged with laying out a pre-sold spruce budworm sale which were all streamside trees up bottoms surrounded by lodgepole. I bring that up only as an example how often the Forest Service has changed and chased many different forest treatments for a variety of usually erroneous or oversimplified reasons. DDT for spruce budworms, pulling Ribes for white pine, creating patchwork of even age stands are a few more examples

And now the Forest Service is in the midst of massively increasing fuel treatments as the new panacea for keeping fire dependent forests from burning. On a landscape scale, the fire-dependent Forests of the Intermountain West are generally allocated to something that 1) those allowing or encouraging timber management , 2)Wilderness or Recommended Wilderness, and 3) everything else. The “everything else” lands are usually too steep or otherwise economically infeasible to manage for timber, but can be a significant if not the majority of a National Forest. Yet the Forest Service continues to attack low or moderate intensity fires relatively successfully on the “everything else” lands as if timber values were to be lost or the ecosystem will be damaged. So these “everything else” lands continue to build unnatural fuel loads and suffers loss of diversity as the forest replaces meadows and grasslands. This month the Bitterroot Forest continued to attack a reburn on a 20 year old burn that is a very dense jackstraw of fire killed downed lodgepole that is impenetrable to anything without wings. What is the end game for these “unmanaged” lands? Will managers just write off the importance of diversity on these lands that only fire can provide by continuing to attack fires in a fire dependent forest ?

Having managed a Ranger District, I am all to aware of the limitation of scale that prescribed fire can accomplish. Smoke constraints, short or-non-existent burning windows and limited manpower combine to make prescribed burning as administered today a very limited option at any measurable scale.

I remain open to other ideas, but realistically many of the current practices are no longer appropriate. In addition, owners of structures in fire zones must take preventative action or accept that land managers can no longer be held accountable for wildfire. Insurance companies could accelerate this greatly if they based fire insurance rates on individual structure risk rather than spread those costs to a wider pool.

At the heart of this debate is “commercial thinning”. However, there seems to be many opinions of what they are, and what they aren’t. For the sake of argument, we should consider “thinning” to mean leaving the overstory in place. There are only a few kinds of commercial logging projects within the Forest Service. I suggest we use those standard terms, for better transparency.

Most thinning projects I have worked on have other objectives than just wildfire safety. Silvicultural objectives are major parts of thinning projects.

Thinning can be very destructive to ecosystems. The thinning done in the SFNF is so aggressive that treated forests oftentimes no longer resemble forests, but instead open, relatively barren and ecologically broken novel landscapes. If you “thin from below” so aggressively that the vast majority of trees are removed, along with virtually all understory, I cannot imagine what silvicultural objectives are being achieved. Certainly not resiliency and certainly not any kind of “forest health.” And then they burn off new regrowth at much too frequent intervals so the forest cannot ecologically recover.

I certainly cannot defend ‘over-logging’, especially in those drier mountain landscapes. If you are going to thin, you should leave the best of the best. I also think that such a massive thinning (to reach a desired ‘trees per acre’ number), should be done in two stages, to ensure that proper stocking will occur, despite unexpected mortality.

The highest value to protect in those landscapes are the genetics of those vigorous surviving trees. Their log value is very low, compared to their future offspring. If the Forest Service has to cut all those older trees, in order to “make the sale go”, then it shouldn’t be a timber sale.

Correct Larry, we need to separate the pepper from the fly poop. However, Region 3’s “restoration prescription” IS a commercial thinning that includes overstory trees. The analogy with the “restoration prescription” is the spotted hog/spotted dog concept, leaving fire proof (my words, can’t remember the proper term – forgive me Richard Reynolds) openings within the stand. GTR 310 is developed to demonstrate the concept. It was developed and implemented on the Apache-Sitgreaves, and THE treatment that protected the towns in Wallow.