This is posted with the permission of the author, Sarah Hyden. Here is a link to the original. I thought she raised some interesting questions worthy of discussion.

Forest Service wildfire management policy run amok

From suppressing fires, to confining fires, to expanding fires, to igniting fires

One of the most important roles of the US Forest Service is to contain wildfires. Firefighters can often help to prevent wildfires from becoming disastrous to the human environment — they can help to protect communities, along with homeowners’ own efforts to fireproof their properties. However, Forest Service wildfire management policy can also cause the destruction of communities, and result in excessive and overly-frequent burning of some of our most valuable natural resources such as old growth, sensitive species and their habitats, and watersheds.

Conservation scientists strongly support “managed wildfire for resource benefit,” which means allowing naturally ignited wildfires to burn when safe to do so. When this is done, fire lines are built to protect communities and other values that could be impacted by the wildfire. This helps to return the natural role of fire in our forests, because fires of all intensities have a role in forest ecology and can promote biodiversity. However, there is also a limit on how much fire is beneficial to forests – too much fire can occur too fast when fires are intentionally ignited.

An increasing trend in Forest Service wildfire management tactics has been to combine intentional burning (prescribed burning) with emergency fire suppression. During at least three fires in New Mexico in just a little over a year, the Forest Service has utilized aerial and ground firing operations to expand wildfires, and to implement intentional burns on landscapes that would not have burned otherwise. These are the Black Fire in the Gila and Aldo Leopold Wildernesses, the Pass Fire in the Gila National Forest and Gila Wilderness, and the Comanche Fire in the Carson National Forest.

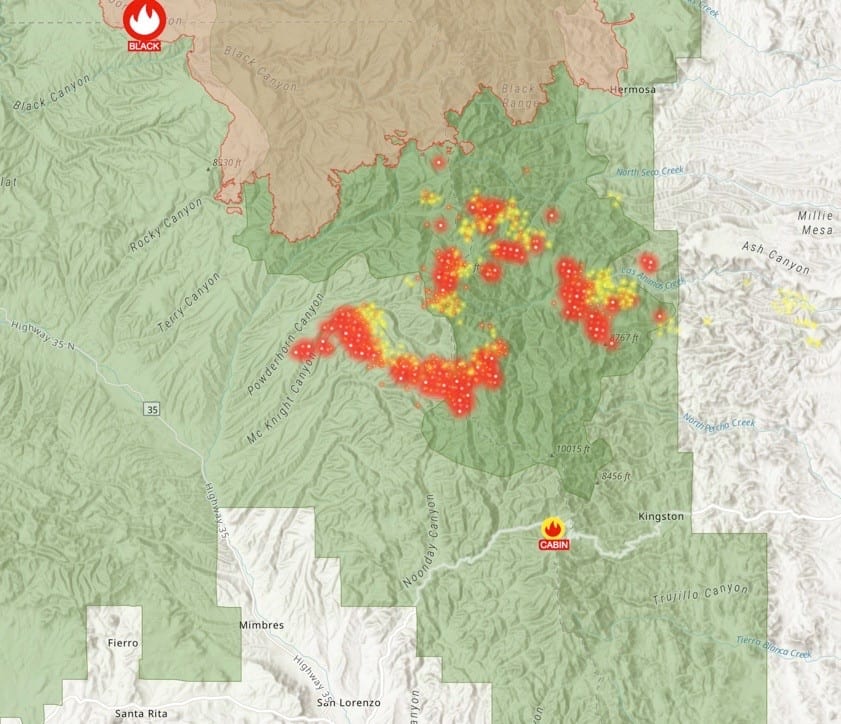

During the more than 325,000 acre Black Fire which ignited on May 13, 2022, it appears from ArcGIS aerial fire hot spot maps, that a very large area of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness was ignited by the USFS up to 10 miles to the south of the main fire with aerial firing operations – meaning dropping incendiary devices from helicopters or drones. See map below. This was clearly not any kind of large-scale back burn intended to contain the main fire, due to its distance from the main fire and its position relative to the wind direction.

This intentionally-ignited fire was herded to the north over several days until it joined the main fire. Then, on the Forest Service’s official fire perimeter map, both fires were suddenly joined together as one fire. There was no distinction made between the original fire which was not caused by USFS actions, and the sections of the fire to the south, amounting to a separate fire, that were directly ignited by the Forest Service. The agency had also expanded the main fire in other directions.

The intentional fire was only stopped by monsoon rains and by the intervention of a Sierra County Commissioner. Shouldn’t there have been a public analysis process before burning most of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness?

The ignitions by the Forest Service, along with the main fire, created a boxing-in formation — fire burning in almost every direction, so that which was in the midst of the formation was surrounded by fire. During wildfires, and also during traditional prescribed burns, wildlife has the opportunity to escape because the fire is generally approaching from just one direction. In a boxing-in fire formation, wildlife can become trapped and either injured or incinerated. There are no opportunities before such on-the-spot firing operations to seriously consider habitats of sensitive and endangered species, or to protect old growth forest and other values.

During the Pass Fire, which was ignited by a lightning strike on May 18, 2023, a substantial section of pinon and juniper in the Beaver Points area was intentionally burned through aerial firing operations, and many other areas were burned in ground firing operations. The ground firing operations were described by the Forest Service as burn out operations, in order to contain the fire and to protect structures. However, those burn out operations seemed very excessive, and some observers considered them to also be intentional burning.

This fire was managed as a “confine and contain” operation – an operation intended to allow a wildfire to burn within a determined fire perimeter for the purpose of reducing the intensity of future fires and to ecologically benefit the landscape. At the beginning of the fire, the Forest Service published on the Gila National Forest Facebook page a map of an approximately 75,000 acre planned fire perimeter. The current fire perimeter almost exactly matches the originally published planned perimeter. See overlay of both maps here.

The Comanche Fire, which began on June 8, 2023, was essentially a prescribed burn, except that the USFS utilized a 20 acre lightning strike ignition as the “match” that lit the fire. They stated in a fire update on June 21 that they have completed, not contained, 1% of the operation at 99 acres, making it clear that they were burning intentionally. The designated “focus area”, which appears to be a planned containment perimeter, was about 10,000 acres, broken into burn units. The intent was to expand a small lightning strike fire to at least 100 times its original size, utilizing both aerial and ground firing operations. The current size of this fire is 1,974 acres.

Such operations are now a substantial part of the work of firefighters across the West. Firefighters are essentially being used as intentional burn crews to implement fuels treatments, carried out with emergency fire suppression funding and no National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) analysis. Some Forest Service personnel believe that we conservationists, by “holding their feet to the fire” to analyze intentional burn operations according to NEPA, are slowing down implementation of burn treatments. So, by expanding wildfires, or even starting new ones in the vicinity of wildfires, the Forest Service is able to greatly expand the implementation of burn treatments, and thereby meet agency quotas.

Any statistics or research about the extent of wildfire in recent years, in relation to climate change or presumed increases in wildfire activity, may be distorted by a substantial portion of total reported wildfire acreage being actually ignited by the Forest Service. This occurs while managing wildfires under full suppression, and in confine and control operations.

The Forest Service has put the concept of managed wildfire for resource benefit on steroids, often using wildfires as opportunities to ignite yet more fire, and to broadly burn landscapes. This is not managing wildfire, but essentially creating fires. They are now using our firefighters as agents to carry out this dangerous and possibly illegal policy that sometimes causes severe unintended consequences to forests and communities. That some burns are ultimately ecologically beneficial does not make it acceptable to carry out fuels treatments without a NEPA process.

Forest Service Chief Randy Moore’s “Wildfire letter of intent 2023” provided direction to agency staff regarding wildfire suppression, stating “We will also continue to use every tool available to reduce current and future wildfire impacts and create and maintain landscape resilience, including using natural ignitions at the right time and place in collaboration with tribes, communities, and partners.” While there is not necessarily a legal basis at this point even for this direction, Forest Service firing operations that expand wildfires cannot be considered to be using natural ignitions. Drones or helicopters dropping incendiary devices are clearly not natural ignitions. And firing operations miles from a wildfire cannot reasonably be considered back burns that are necessary to contain a wildfire.

We have no national wildfire policy that either allows, or places any limits on such operations, and emergency fire suppression funding is not allocated for implementing fuels treatments. The Forest Service has given themselves virtually a carte blanche to conduct intentional burns over a wide area nearby wildfires — all without NEPA analysis or any public involvement in the planning process.

A genuinely cohesive national wildfire policy is essential, analyzed through a comprehensive and open NEPA process. It is necessary to make sure fires are managed safely, and that values like old growth trees, wildlife and their habitat, water quality, and soils are protected. Public health in relation to the smoke generated during intentional burns must also be considered.

The purpose of NEPA is so agencies will “look before they leap,” and therefore avoid causing environmental disasters. We have had more than enough disasters occur, culminating with last year’s Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire. If we allow the Forest Service to largely jettison NEPA and to freely implement fuels treatments under the guise of emergency fire suppression, we are giving up our primary means of protecting our forests and our communities, and it will affect other important conservation priorities. NEPA law acknowledges and supports our right to have a say on what occurs in our forests, and requires comprehensive analysis of the impacts of proposed actions.

The Forest Advocate is investigating USFS firing operations and will report more later. In the Forest Service Southwestern Region, a substantive FOIA request can take years to be fulfilled, so some records are difficult to obtain. The Sierra County Commission made an information request to the Forest Service to provide records of aerial ignitions during the Black Fire, but were told by the Southwestern Region that they have to put in a FOIA request through the standard process.

We need our elected representatives to urge the Forest Service to disclose the extent of all ignitions intended to expand wildfires or ignite new fires, especially during the Black Fire – and to move forward with a revised, comprehensive and clear national wildfire policy, accomplished in a transparent way, in accordance with environmental law.

Please include me in this discussion and followup.

Good to see this post. And, very good to see people taking a look at what appears to be wrong-headed managment of the national forests when fires are made bigger and more destructive. In my view, most all managed fires must be stopped. Given the new climate don’t worry, plenty of fire will be on the landscape in the next few decades. This will happen because certain fires are just to hot to stop right from the beginning. Here in California a few forests have ended “managed fires” altogether. They are the Klamath, the Shasta-Trinity, the Mendocino, and (( think) the Plumas. Such a great percentage of these forests have burned catastrophically in the last two decades that the FS has finally gotten the point. Hopefully this trend will continue.

Sarah Hyden has hit on one of the “hard truths” that has come out of weaponized Appeals and litigation. Harkin this article to that of Lynn Bennet’s and you begin to see the contrast in forest policy implantation, from the “it doesn’t say you can” to “it doesn’t say you can’t” philosophy. As it stands now, managed fire allows the practitioner to accomplish “gobs” of acres under the resource benefit moniker, without any pesky meddling from the public. The upward chain of command will be impressed, and of course “it doesn’t say you can’t”!

However, new Plan Amendments and updated Forest Plans can involve the NEPA process to identify management areas and objectives, with public input. My involvement with the Apache-Sitgreaves Revision adopted a pre decisional “trigger” in the Plan Revision. I was gone as Forest Sup by the time it was signed, but was “handed” the development and got it to signatures, Washington Office and Hill briefings included!

Managed fire, whatever that now entails, is certainly a double edged sword, but too many Line Officers are judged (as in career opportunities and budget implications) on meeting the targets set for WFU, including prescribed fire. Congress, in all its wisdom, generally finds a new and better solution to a conceptionalized problem – real or imagined, and acres burned seems to fit that bill. After all, we (USFS) asked for it, right? I mean, the answer to everything from climate change to cleaning campground toilets seem to include acres burned….

Managed fire used to be a very difficult decision to make; I spent many a sleepless nights after signing off on such proposals, similar to large fires and concern for firefighters well being. I had a few “go over the hill”, but never taking more than minor (?) timber or rangeland assets. I really don’t understand the philosophy of just another “lessons learned” or “learning journey”; I think heads should roll when disastrous results such as the New Mexico debacles of 2022 occur.

So here is my question, what would it look like to involve the public, even if a revised Plan “says you can”? Certainly, it would have to be pre approved; there is no time to call all interested parties over coffee, most of the time we only have hours to make the call. Is there an unspoken authority (given the required fire management for Line Officers and delegated authority) at play here? I think it’s time the FS comes clean on this!

After all, wouldn’t it be great to be as concerned with “volume produced” as “acres burned?”

Good question, Jim!

Does anyone have a fire amendment or part of a plan that described how the public is involved after the amendment or plan is approved?

Most of these efforts are cursory or laughable. Most Forest simply and falsely assert managed fire is in line with Plans written two decades ago. Others (Tonto NF) claim burning 50,000 acres is a FONSI and decision memo. With one or two exceptions, Forest Supervisors are doing the absolute minimum of scoping, public involvement, and alternative actions. It’s a paper-thin defensive move to try to ward off increasingly effective pressure to follow administrative and substantive laws.

Tom Tidwell signed the Chevron Deference in 2009 as a Carte Blanche to govern fire until some disaster or lawsuit drags it to a halt. You hit the nail. “Doesn’t say you can” to “Doesn’t say you can’t.” I think it does say you can’t, not without disclosing cumulative effects and building informed consent with the people at risk. The FS has effectively claimed hegemonic control over all lands, all ownerships, by unilaterally burning the NFS (and the neighbors). It’s not a cooperative or collaborative decision in any way. When our Forest Supervisors let fires burn and then actively expand them and the fires “escape” they are seizing private property for public purposes. The FS has no Power or authority to fix what they break.

We (PFMc) have been studying this issue since the 2012 Flat Fire at Del Loma near Big Bar in the Trinity Alps. Tim Ingalsbee first published a study of the Big Bar Fire showing that 40 percent of the total burned acres were lit intentionally and in excess of suppression needs. Using that study we asserted the Flat Fire was intentionally burned to encompass 1,600 acres and 10 days of expensive firing ops to execute a preplanned Rx burn. That small triangle was the last unburned land in the Trinity Alps. Randy’s FS invented Enhanced Cost Recovery as a way to stick egregiously high firefighting cost to private parties and charged two small companies $12.6 million for the Flat Fire. Randy used a tiny roadside fire to do a project Rx fire at the height of summer and then forced private companies to foot the bill. In subsequent years we discovered hundreds of examples of misappropriating public money allocated for “emergency fire suppression” being used as an open checkbook for prescribed fire. When we realized the scope and scale of fire drones being used to big box the Gila’s Black Fire, I put together a compelling look at several examples of free range burning at the height of fire season including a major mistake in California that led to 16 civilian deaths. I convinced Sarah Hyden and her contemporaries in the Santa Fe Conservation community to hear me out. I made a Zoom presentation to her and she recorded it. Over the next several months and after exhaustive footwork of her own to follow up on my leads and contacts, Sarah wrote this great article which I completely endorse. The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Strategy is a smokescreen designed to make unilateral Forest Service intentional burning of public and private lands look like a group effort. It is not. By hiding behind the 1984 Chevron Deference, the FS has assumed de facto control over public and private ground. They are avoiding APA, NEPA, NFMA accountability, and all of the substantive laws like Clean Air, T&E, and ARPA. Any honest FS employee/retiree should be appalled by what our Green Team is doing. I wish you could read the letters we receive on the impacts of these Rx Wildfires. We want the FS to stop, publish SOPAs, scope, propose an action, invite comments, provide for objections, sign a RoD, and then we will all understand the cumulative effects and costs/benefits of Restoration Wildfires. And the FS can finally confront the astonishing destruction of their perfidy.

Frank, I don’t know of anyone who is against doing fire management amendments with public input that lay out PODs, prescriptions and locations of fuel breaks, prescribed burning and what areas under what conditions can be managed for WFU.

Maybe fire people aren’t planners, and planners are too occupied with other aspects of plan revisions? Clearly if it’s important, we can’t wait for plan revisions to be completed for all the forests.

What do FS people say when you ask them that question “why not do fire management amendments?”

Hi Sharon. You know lots of them. Their answer is they don’t have to do APA NEPA NFMA etc. because the FS has Alternative Arrangements AAs for Wildfire funded by WFM “emergency fire suppression” appropriated dollars. It’s why Fire Teams obfuscate, stay coy in communications, fail to mention what they’re actually doing. The Gila bravely broke the mold after intense pressure from us and Sarah and Jim Paxon. Midway through the Pass Fire this year they dropped the “emergency” and “wildfire” pretense and told the public they were burning on purpose for resource benefits. The FS has maddeningly used (or failed to correct) the climate change narrative in their own or media use to cover every fire activity. Academics, retirees, SAF, NARFSE are almost universally clueless about the scope and scale of summer “firing ops.” It matters that we all understand. On the North Complex in 2020 “widespread firing ops” (IAP for September 3-8) in the face of predicted red flag conditions on September 9 resulted in 180,000-acre firestorm that killed entire herds of wildlife and cattle and burned 16 civilians to death. We are waiting to see an FLA on that fire. The reason all of this matters is because hundreds of studies, scientific and professional papers, and hugely expensive agency plans are all operating with virtually no understanding or even awareness of how consequential burning on purpose has become. It’s not fall back to the next best ridge anymore (M. T. Rains). Now it’s fall back 25 miles (Telegraph and Bush) or drop south 10 miles and burn with no firelines (Black). The FS has given up on fuel treatment other than fire. Rangers and Supervisors are increasingly coming from Fire ranks. Fire has $5 billion and Planning has a billion. Let’s stop and engage the Nation in the conversation. When I asked Shawna to ask Teams to track miles of indirect line constructed and estimate acres burned on purpose on each fire, I got silence. Now, I also want to know acres burned in drone and helicopter strikes where no indirect line was built at all! (Coffee Creek and Black/Pass). So much information. You really have to follow FS fire actions on a scale only outsiders can attempt.

Thanks Frank

I still don’t understand the incentives for this behavior, why they have changed, or why the disincentives have changed over time.

We need to write a comprehensive history of Forest planning. I have a 1970 memo from RF Bill Hurst to all personnel R3. He is so excited to tell everyone about the dawn of a New Age where the FS is going to engage the public in running the Forests. I joined the Coconino planning team in 1980 to help stuff a “three-year process” into seven very long years. 10-hour days, 6 days a week. It started on a high note. As time went by, Robin Silver and Kieran Suckling learned to stop, stymie, change, and harass us to the point of despair. They found that a ten cent stamp and an agency legal department’s unwillingness to actively defend FS decisions was enough to direct the NFS and FS according to their own very narrow lights. They attacked everything. Inexorably, the FS ground to a halt by 2000…except for fire. Tom Harbour responded by beginning to build the greatest Fire Empire in the history of the World following the disastrous fires in Los Alamos and elsewhere that year. Tidwell responded by signing the Chevron Deference in 2009. OC responded by writing the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Strategy in 2014. And the Fire horses hit the ground running and never looked back. We learned to ignore and defeat Robin and Kieran by pivoting our entire efforts into using the only tool we have that is not subject to objections, oversight, fiscal limits, or in any other way. The ant said, “If it tastes good, I haul it. If it doesn’t, I don’t.” The new leaders of the Fire Empire are no longer interested in planning or the law. They suppose their Alternative Arrangements for “emergency fire suppression” are sufficient for the day. There is no incentive to sacrifice any aspect of total agency control over “wildfire” to the tyranny of the 1990-style dysfunction that destroyed our ability to actively manage the NFS.

Well there is that.🤣🤣🤣 I guess you and I are outcasts Frank, or maybe it’s just a Region 3 thing, I don’t know, but I followed every line, nodding and saying “yep”. It’s just unfortunate we have taken the path of destruction over good old fashioned “dirt forestry”. I picked up a FS brochure yesterday and it was so filled with such nonsense I just threw it away. All the resiliency and climate modeling, rolled up in the Milky Way can’t replace good old fashioned forest management!

I’m curious what you are referring to as “the Chevron Deference.”

Maybe it’s worth a closer look at “alternative arrangements.” The Forest Service won a lawsuit on this in 2017 (FSEEE v. USFS) on the Wenatchee, but on a different set of facts, it’s conceivable a court might find that a particular action was not necessary for the specific “emergency” conditions (perhaps the Bitterroot example mentioned elsewhere in this thread).

https://www.gardenlawfirm.com/court-finds-forest-service-not-need-conduct-environmental-review-constructing-firebreak-existing-wildfire/ https://casetext.com/case/forest-serv-emps-for-envtl-ethics-v-us-forest-serv

We also keep hearing about having summer prescribed burns within the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit. Some prefer the risk of the fire’s escape over the possibility of smoke in the fall and spring. Yes, there is often a temperature inversion, trapping pollution over South Lake Tahoe. There are still places in the basin where trees that died in the early 90s bark beetle event are still on the ground, waiting for that inevitable wildfire spark.

This is just a general impression from years ago, but the fire organization in the Forest Service was not a willing cooperator in meshing forest planning and fire planning. It seemed like some believed they were exempt from NFMA (as well as NEPA). The regional fire person assigned to planning always had fire priorities that were higher than working with forest planning. I was a little involved in one national effort to coordinate the two that showed some promise, but it apparently sputtered out when the staffer who believed in doing that (who didn’t seem to be getting a lot of support) moved on.

WFU is a term of art, where if a natural ignition occurs, the fire is allowed to burn, however this policy is not anchored in appropriation law. The annual appropriation for “wildfire management” (Democratic drafting) and/or “wildfire suppression” ( Republican drafting) requires every wildfire fire to receive the emergency suppression response. Starting with Wildland Fire Management (WFM), what does Congress mean? Congress intends by the appropriation language to ensure a policy directed at putting out all wildfires irrespective of ignition source as rapidly as possible, which it terms as “emergency wildfire suppression.” An emergency is an urgent, sudden, and serious event or an unforeseen change in circumstances that necessitates immediate action to remedy harm or avert imminent danger to life, health, or property; an exigency. Suppression is the controlling and extinguishing of fire.

Since the inception of the National Fire Plan (2,000), WFU has come at the expense of appropriations and the law. The National Cohesive Strategy (2009) placed the WFU in an extracurricular status whereby WFU was funded by WFM (emergency suppression appropriations) but the fires in question were allowed to burn, without much suppression action or enhanced to burn with firing operations on-the- ground and in-the-air, usually to achieve the noble goal of returning fire to the ecosystem.

The National Forest Management Act (NFMA) has 3 references to fire – as damaging. The Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act has no references to fire. However, the Organic Act has this about fire: “The Secretary of the Interior shall make provisions for the protection against destruction by fire and depredations upon the public forests and forest reservations which may have been set aside or which may be hereafter set aside under said Act of March third, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, and which may be continued; and he may make such rules and regulations and establish such service as will insure the objects of such reservations, namely, to regulate their occupancy and use and to preserve the forests thereon from destruction; and any violation of the provisions of this Act or such rules and regulations shall be punished as is provided for in the Act of June fourth, eighteen hundred and eighty-eight of the Revised Statutes of the United States.”

NFMA did not repeal this provision of the Organic Act. Nor does NFMA specifically modify the annual appropriations law. This means as a matter of appropriation law, WFU in land and resource management plans; or as a specific amendment to the existing plan would be non-conforming to the annual appropriation bill. In other words, illegal. This is because the annual appropriations can only fund activities and projects that conform to authorizing law (NFMA, MUSYA and the Organic Act).

The Uinta/Wasatch-Cache NF(s) has a specific land and resource management plan (LRMP) for the Uinta. In that plan WFU was programmatically authorized, but never analyzed site-specifically in a failure to follow the 2-step planning/implementation policy of the Forest Service. Instead, a red/green map was produced, whereby fires were suppressed in the red sections on the map and allowed to burn flagrantly in the green section of the map. The Uinta covertly took advantage of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) Alternative Arrangements for compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act granted to the Forest Service. While their LRMP was permissive toward fire use, the managers failed to analyze the site-specific consequences of permissive fire use. In addition, the Uinta has another paramount problem, which is by using emergency suppression appropriations, to achieve LRMP objectives it is misappropriating funds.

In August of 2018 at Pole Creek, a lightning strike was allowed to burn in violation of the appropriation law for FY 2018. A 300-acre maximum management area (MMA) was drawn around the ignited downed-log. However, the fire self-extinguished despite the best efforts of the Uinta. Plan B was then invoked where the remaining 299 acres of the MMA were ignited. Then there were days of red flag warnings for high wind and low humidity. The Pole Creek then merged with the Bald Mountain fire and burned 96,000 acres. That is the story of WFU. Many WFU fires end as large cataclysmic events, damaging lives, property and the national forest.

This example of WFU and many others demonstrate why fires are now perceived to be larger in size and more expensive to control.

This sounds like an interesting point: “This means as a matter of appropriation law, WFU in land and resource management plans; or as a specific amendment to the existing plan would be non-conforming to the annual appropriation bill. In other words, illegal. This is because the annual appropriations can only fund activities and projects that conform to authorizing law (NFMA, MUSYA and the Organic Act).”

My exposure to federal appropriations law is meager and rusty, but I don’t think I agree. NFMA says “Resource plans and permits, contracts, and other instruments for the use and occupancy of National Forest System shall be consistent with the land management plans.” This means funding for fire management must be consistent with the forest plan rather than the other way around. Also, since appropriations only govern what money is spent on, I don’t see a way that a normal appropriation bill (without some extreme riders) could determine the substantive outcome of that spending (forest plans). Past practice is no guarantee that a forest plan that seems out of step with current funding won’t be be funded in the future.

I agree that there seem to be some questions of compliance with appropriation bills in how the agency funds fire-related activities. I would interpret “a lightning strike was allowed to burn in violation of the appropriation law for FY 2018” to mean that suppression dollars were used to do something that was not related to fire suppression. That might be a hard case to make. (If they did nothing at all, that could not be characterized as misuse of funds.)

That is a common misconception of the National Forest Management Act (NFMA), which is itself an amendment to the Resources Planning Act (RPA). Part of the RPA was to allow the Executive Branch to dictate to Congress what programs and amounts to fund the Forest Service with each year. But the time-honored adage of the Executive proposes and Congress disposes has prevailed.

Expenditure of funds for WFU of a natural ignition or human-caused ignition is outside of the Wildfire Management Appropriation because expending funds in that manner is not suppressing the wildfire as an emergency, even if the unit land and resource management plan is permissive of WFU. Congress has termed the expenditure of funds “emergency wildfire suppression.” The key words and plain meanings in this appropriation provision take precedent. NFMA is an authorizing law and by definition appropriates zero dollars. The real power is appropriations law, which means that it takes precedence over NFMA. In NFMA, fire is considered an impact to resources and other attributes defined in the law. The Organic Act still in effect, is specific in its direction to the Secretary on how to address wildfire: “The Secretary of the Interior shall make provisions for the protection against destruction by fire and depredations upon the public forests and forest reservations which may have been set aside or which may be hereafter set aside under said Act of March third, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, and which may be continued; and he may make such rules and regulations and establish such service as will insure the objects of such reservations, namely, to regulate their occupancy and use and to preserve the forests thereon from destruction; and any violation of the provisions of this Act or such rules and regulations shall be punished as is provided for in the Act of June fourth, eighteen hundred and eighty-eight of the Revised Statutes of the United States.” WFU under the annual appropriations act cannot be squared with this provision, because the Organic Act still applies.

“This means funding for fire management must be consistent with the forest plan rather than the other way around.”

What do you mean by this? Are you saying deliberative burning for hazardous fuel reduction under the appropriation for the National Forest System would have to be consistent with the land and resource management plan? If so stated, that is relying on a separate and distinct appropriation and I agree would have to be compliant with the land and resource management plan for that unit. This is because Congress has designated a specific dollar amount in the National Forest System appropriation for hazardous fuel management activities. The management activity can be mechanical, biological/chemical or burning (pile and/or broadcast) and would have to be authorized on the land and resource management plan and site-specifically analyzed and disclosed through the National Environmental Policy Act and the Administrative Procedures Act.

“Are you saying deliberative burning for hazardous fuel reduction under the appropriation for the National Forest System would have to be consistent with the land and resource management plan?” Yes.

I’m also saying that appropriations language does not prohibit forest plans from authorizing WFU unless particular legislation puts that specific restriction on funding forest planning (which would have no effect on existing plans). I don’t know if that’s where you are going with this, but I see no conflict between WFU and the Organic Act’s “preserve the forests thereon from destruction,” which WFU is intended to do. (And hasn’t at least one national forest adopted a WFU amendment to specifically authorize it?)

So, you say “it doesn’t say they can’t, so they can?” Appropriations law is specific. Misappropriation is illegal. Among other things you can’t do is misuse dollars marked for emergency fire suppression to instead pay $1 million/day to keep T1 teams in the field not suppressing the fire. You say burning at this scale aligns with Forest Plan objectives? How do you know? There’s been almost no unit analysis. MUSY requires forests to be conserved and sustained in perpetuity. How does leveling Berry Creek conserve that mature and MOG Forest? It’s gone now.

I don’t think we are disagreeing on appropriations. The FS has to be able to link its activities to an appropriation. It’s not clear to me what those teams would be doing if they are “not suppressing” the fire. If they are encouraging more fire that can’t be deemed necessary for suppression, they could be misusing the funding. But they’re going to get the benefit of the doubt on this, and I’m guessing that Congress would be a better forum than the courts.

I did say that if an activity can’t (even with that benefit of the doubt) be described as necessary for suppression, then there needs to be analysis showing it is consistent with the forest plan. (I would say that suppression has be consistent with a forest plan, too, but I assume all plans are written to make sure that is true.)

What do folks think of NPS using the same tactics? From Inciweb today for the Pika Fire in Yosemite NP:

“Yosemite Fire crews are using a confine and contain strategy utilizing natural barriers and trail, using fire to secure and strengthen control lines. The fire has moderate growth with some isolated active pockets northwest of North Dome.

A confine and contain strategy under favorable conditions allows fire to move naturally across the landscape, providing ecological benefits to plants and wildlife, while also meeting protection objectives to minimize risk to people and infrastructure.”

The Park Service has attempted to do the NEPA and has completed EAs and EISs. Their actions have been catastrophic. They are burning the Old Trees to death at a high rate.

Yosemite National Park has often claimed they have an enlightened view of fire and nature. However, their track record has been pretty bad, in some cases. They used to let fires burn, until they get completely out of hand. Their prescribed burns have had their problems with catastrophic escapes. They do know they need to do better, and it looks like they are getting it right with the Pika Fire. It is a worthy goal to restore frequent fire, with little damages occurring, as the fire speeds through the light and flashy fuels. However, it is important to reduce the fuel loads, so fires can burn without destroying old growth, and other important ecosystem features.

Just as bad is the USFS practice in Montana of using “emergency fire suppression” as a way to accomplish commercial logging projects without NEPA review, often miles away from wildfires. For example, in 2022, Bitterroot National Forest commercially logged a 120-acre square that almost exactly coincided with a 2014 proposed commercial timber project that did not make it through NEPA review. But, with a wildfire burning more than 6 miles away, deep within the Wilderness, they used the “emergency fire suppression” excuse to finally do the project anyway. The only fire model they were able to produce showed an almost 0% chance of ever reaching this “fuel break”—it was late September, near the end of the fire season here. The funny thing is that the fuel break was discontinued to the south where the commercial timber ran out, even though there was also another fire there burning a similar distance back in the wilderness. Although 120-acres is not on the same scale as the fires you are discussing, the project not only destroyed a long-term climate study site, it severely degraded an area valued by locals for its relatively pristine mature forest. Emergency fire suppression provides the perfect cover to make timber targets, or prescribed burning targets, or fuel reduction targets without going through NEPA.

This case would completely overturn the Chevron deference which allows agencies to make laws out of thin air. What Jim Zornes characterizes as “doesn’t say you can’t.” It would end the entire foundation of “managed fire” absent actual laws and following current laws like APA and NEPA.

https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/eenews/2023/07/18/fishermen-launch-supreme-court-war-over-chevron-doctrine-00106818?source=email