From onX report here.

From onX report here.

For our recreation readers:

Here’s a very interesting story, which, for me, had an unexpected twist near the end. Or even in the tagline.. “Researchers find as more humans play outside, a smaller proportion are engaged in stewardship that can protect the lands from growing impacts.”

A black bear padding through the forest freezes. It looks up briefly, then something spurs it to turn and bolt in the other direction.

That something is the sound of hikers — a recording of women’s voices in conversation as they walk along a trail. It is emitted by one of many motion-triggered speakers scientists set up in the Bridger-Teton National Forest as part of a study on the impacts of outdoor recreation sounds on wildlife. And as this grainy game camera footage shows, even sounds that appear benign to us humans can disturb animals.

I wonder whether researchers need to put up signs that peoples’ conversations may be recorded?

It sets out to answer several questions, Zeller said, primarily: “Do mammals have increased stress or vigilance or other types of potentially negative behaviors when they hear recreation noise?”

They also want to know if birds avoid noisy areas, if animal communities change group behavior and what types of sounds are most impactful.

Ditmer and Zeller are only partway through data collection and haven’t quantified responses, but Zeller said they’ve seen many spooked animals — and one activity appears to be particularly startling.

“We’ve found that mountain biking with a large group size tended to result in a higher probability of wildlife fleeing a site compared with the other sound treatments,” Zeller said.

*******************

And yet, human hunters would also cause increased stress or vigilance. If you’re curious about the interaction between ungulates’ vigilance toward hunters vs. wolves, there’s a study with red deer, wolves and hunters in Poland.

Those observations align with a 2016 study co-conducted by Courtney Larson, a Wyoming conservation scientist with The Nature Conservancy. Larson and her co-authors reviewed scientific literature regarding the impacts of non-motorized, non-consumptive recreation on wildlife. Some 93% of the nearly 300 studies that assessed recreation’s wildlife effects found at least one significant effect, most of which were negative, according to their findings.

Those effects can look like habitat fragmentation, or animals spending more time being vigilant and less time feeding, Larson said during a presentation in Laramie this spring. Awareness seems to be growing and people have good knowledge of times of year or places where wildlife are particularly vulnerable, she added. But questions remain on the varying sensitivity of species as well as how much recreation a landscape can hold.

*******************

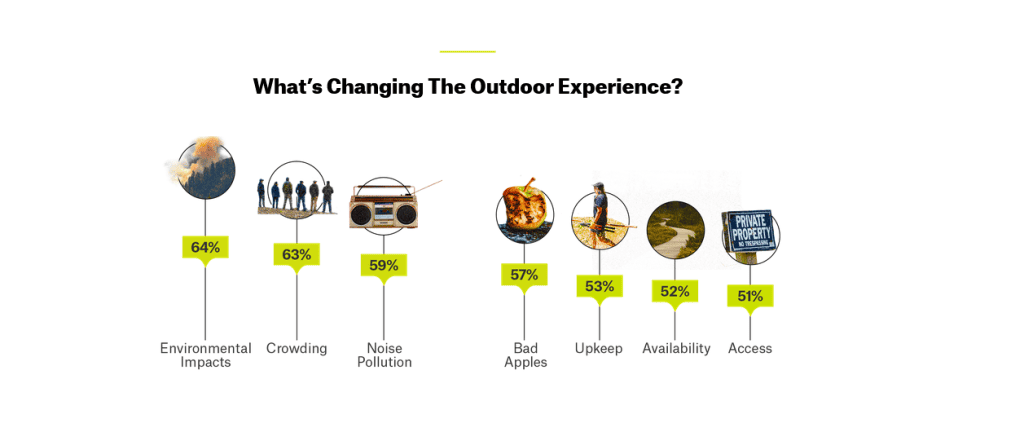

Deteriorating experiences on public lands are on the rise, their study found. “So some of the biggest changes to our outdoor experiences are those caused by the very people that are enjoying the outdoors,” said Becky Marcelliano, onX stewardship marketing manager. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents cited overcrowding as negatively affecting their time in nature, for example. Outdoor recreation participation hit a record high nationwide in 2022, according to the 2023 participation trends report from Outdoor Industry Association.

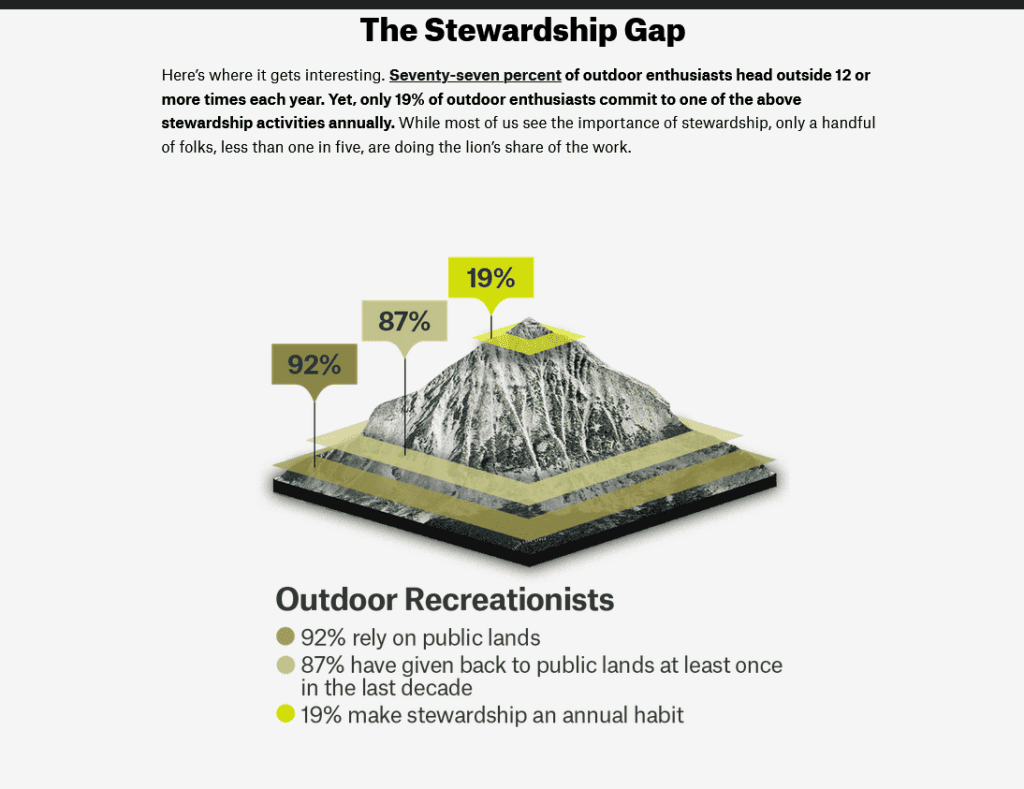

Perhaps the biggest takeaway, she said, is a so-called “stewardship gap.” Though industry data shows 77% of outdoor enthusiasts make 12 or more outings a year, only 19% commit to a stewardship activity in that same timeframe, she said.

“Which means that less than one in five are doing the lion’s share of the work to protect and restore our public lands,” Marcelliano said.

At first I thought this was a little odd. Can’t people just enjoy themselves, and feel glad that their taxes are supporting public lands? If they’re federal, state or county lands, shouldn’t employees and our taxes be doing “the lion’s share”? On the other hand, people should behave as responsible human beings, including as they recreate outdoors. Seems like rules, and enforcement thereof, have a place as well.

Anyway, onX considers these things stewardship.

Next post: onX and access.

I like Wikipedia’s definition of environmental stewardship, which is more in line with the ultimate goal of environmental education: “Environmental stewardship refers to the responsible use and protection of the natural environment through active participation in conservation efforts and sustainable practices by individuals, small groups, nonprofit organizations, federal agencies, and other collective networks.”

In other words, a person who visits a national forest and practices Leave No Trace and/or Tread Lightly skills would be an environmental steward. I would also argue someone who comments on project NEPA is being an environmental steward. The list of things people can do to exhibit environmental stewardship is long and varied, much more so than what falls under onX’s definition.

I like the phrase “responsible use and protection.” That is a whole lot different than passive avoidance, which seems to be how many people are defining “conservation” — which formerly meant “wise use” — in recent decades.