This is an interesting and pretty comprehensive story from the Colorado Sun. Kind of a bee-centric take on desirable vegetation structures. Ecology is a funny thing in that there are all kinds of ecologists interested in all kinds of critters who may not prefer the same kinds of vegetation. So what is the “ecological work” that needs to be done- and what variety of ecologist decides?

The more-than-decadelong effort to thin Front Range forests to reduce fire danger has brought more bees, more flowers and increased resilience to climate change, new research shows.

The raw number and the diversity of bees and plants exploded a few years after ponderosa pine forests were restored to a “pre-European” state, researchers from Colorado State and Utah State universities found.

“We found that if you cut trees and open up the canopy, between three and 10 years later, you see a pretty good response,” said Seth Davis, associate professor of forest and rangeland stewardship at Colorado State University and co-author of a study recently published in “Ecological Applications.”

“Forest restoration and forest thinning is one of the ways that we can conserve our native communities.”

I like that reporter provided the historical context for how these particular forests came to be.

For thousands of years, natural fires have been an integral part of healthy forest ecosystems in the West. Small fires that clear out underbrush every five to 30 years as well as more devastating fires that can raze the forest to the ground every 50 to 100 or more years clear the way for new growth. Native Americans were known to set small fires to clear out undergrowth for better hunting and regeneration of valuable plants, but did not cause major changes in the ecosystem. Then, beginning in 1859, Euro-Americans flooded into Colorado seeking gold and silver.

I’m not sure that’s accurate; not sure that we can know whether larger pre-European fires were set intentionally. Larger fires did occur.

“Suddenly, in a span of decades, the Colorado Rockies were engulfed by this new, highly unpredictable world of commodity capitalism, of smelters and railroad investment, of boomtowns and sudden busts, of landscape changes so fundamental that they dwarfed the modest human impacts made over the prior 10 centuries,” historical geographer William Wyckoff wrote in his book “Creating Colorado.”

Vast swaths of the Front Range forests were cleared to obtain wood for mining, construction and railroads. Extensive fires also surged across the landscape, fueled by accidental and intentional fires.

To combat the rampant and unregulated logging of these forests, the federal government in the early years of the 20th century created the White River, Pike, and Arapaho and Roosevelt national forests along the Front Range and high into the Rockies. At about the same time, firefighters began trying to suppress all fires.

As a result, over the past century, dense forests with thick undergrowth have grown up across the Front Range and the entire West. Many of the plants that thrived in the pre-European forests disappeared from the now shady forest floor. And with them went many of the animals that ate and pollinated them. You end up with a rather homogeneous landscape that doesn’t have a lot of flowers in it,” Davis said. “You end up with a situation where you can’t have a lot of native bees there.”

************

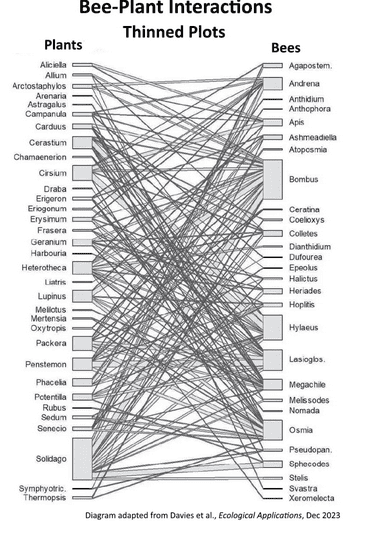

They found an impressively richer, more dense and resilient web of life. While the bee population roughly doubled, the number of interactions between bees and plants rose eightfold and there were five times as many unique connections between specific bee species and plant species.

The researchers illustrated the interactions in a diagram, which visually depicts a richer, more complex web of life.

“Yeah, it’s kind of mind-blowing,” Davis said. “You just see there’s just far more diversity or more complexity.

“You get the idea that if you lost one or two of the flowers or one or two of the bees out of this system, the whole network doesn’t just collapse and fall apart. Whereas on these control plots, if you remove one or two things, you just got a lot more vulnerable ecosystem.”

“This paper is a strong piece of evidence for the ecosystem benefits of forest thinning in areas where fire has been suppressed and the canopy is overgrown,” said Amy Yarger, director of horticulture at the Butterfly Pavilion. She was not involved in the research. “With climate change and biodiversity loss posing existential threats, mindful forest management is key for conservation and for preserving our way of life in Colorado.”

*******************

“Here are some really key species for supporting a lot of biodiversity of pollinators, which in turn supports biodiversity of plants,” said Julian Resasco, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado. “Things that maintain the integrity and the diversity of these ecosystems make them more robust to other threats, like climate change.”

The researchers recommended that forest managers seed ponderosa pine forests with these plants to promote a robust pollinator network. They also could be good plants for people to plant in their gardens. “These are good choices for planting because they’re going to support the bee-flower interaction network,” Davis said.

He believes the environmental benefits extend beyond bees and plants. “We’re sort of measuring one little component of the overall food web here,” Davis said. “By bolstering their abundances, you’re also bolstering the abundances of things which prey upon them, like predators, which could be birds and other animals.” Another study from 2020 suggests that the thinned forests also benefited bird populations.

Not every scientific paper reminds me of an old pop song.. birds, bees, flowers, trees, this paper has it all.

Carbaryl (1-naphthyl methylcarbamate) is a white crystalline solid commonly sold under the brand name Sevin®, a trademark of the Bayer Group. It kills beneficial insects like honeybees as well as crustaceans not to mention its havoc wreaked on fungal communities and amphibians. Sevin® is often produced using methyl isocyanate the chemical that Union Carbide used to kill thousands of people in Bhopal, India. The deadly chemicals migrate easily into waterways then into groundwater.

Insects contaminated with industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals in water supplies are weakening immune systems spreading white nose syndrome to bats as part of Earth’s anthropogenic-driven sixth mass extinction.

On orders from Donald Trump’s Ag Secretary Sonny Perdue and Governor Mark Gordon, the Forest Service, the US Department of Agriculture and the Wyoming Game & Fish Department sprayed the herbicide Rejuvra® with a helicopter on cheatgrass in a 9,200 acre area within the Mullen Fire scar near Laramie, Wyoming with the goal of reducing, maybe even eradicating its presence. People recreating on the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest were urged to avoid the kill zone so imagine the effects on native pollinators and cervid genetics.

Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd) is the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome and in part because of WNS the US Fish and Wildlife Service extended Endangered Species Act protection in 2016 for the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) despite protestations from Republicans. In January of this year the US Fish and Wildlife Service extended the date to the end of March for reclassification of the northern long-eared bat from threatened to endangered. Insects coated with industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals in water supplies are weakening immune systems spreading WNS to bats as part of Earth’s anthropogenic-driven sixth mass extinction.

Last year Colorado officials found Pd in Baca, Larimer and Routt Counties now the National Park Service has detected the disease in a Yuma bat (Yuma myotis) near La Junta. The US Environmental Protection Agency has found that virtually all endangered species are threatened by pesticides like Carbaryl.

In my home state of South Dakota 650 cases of chronic wasting disease have been reported since 2001 and in 2022 34 elk and deer were found to be infected; now, South Dakota beekeepers are reporting massive collapses of colonies because of pesticides. In the northern Great Plains songbirds are losing ground to industrial agriculture.