Story worth reading by journalist Gabe Popkin, including a journalistic shout-out to FIA:

To my mind, the FIA is a national treasure, like the James Webb Space Telescope. There’s probably no comparable public dataset in the world, yet unlike the James Webb, most people have never heard of it.

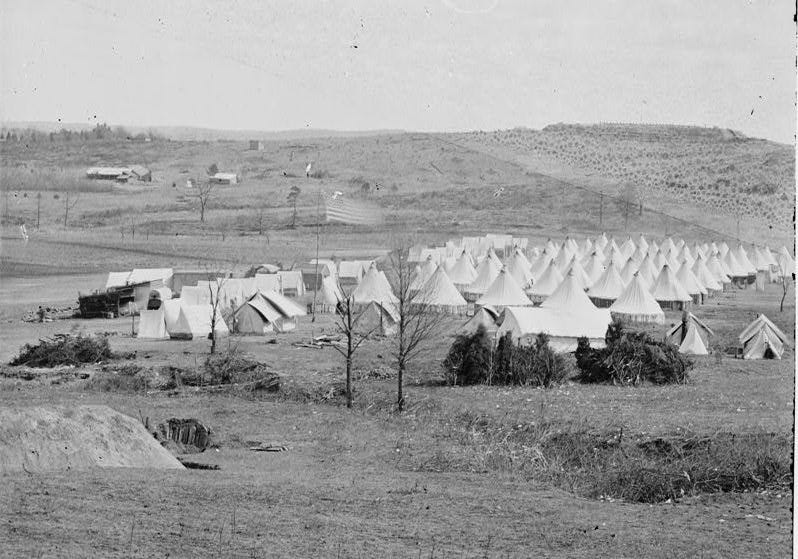

It’s long been known both from FIA and other data that eastern U.S. forests are soaking up carbon dioxide as they rebound from a near-total deforestation that started in the early 1600s and ended only in the early 1900s. One shocking photo I came across recently shows what is now the Brookland neighborhood of Washington, D.C. during the Civil War.

Sidenote: I’ve been reading a memoir by an Alexandria native who describes the Union Army cutting their woodlands for firewood and structures, so I imagine that’s part of what happened to this area as were farm fields.

This desolate scene is hard to square with the lush, green city D.C. is today, especially in outlying neighborhoods like Brookland. Yet around the time of the Civil War, large swaths of the District were apparently nearly as treeless as a western desert — as, indeed, was much of the eastern half of the country.

The scientists found, unsurprisingly, that American forests have bulked up as they rebound from the deforestation that created scenes like the one captured in the photo. While this regrowth will eventually taper off as forests mature, so far it seems to be going strong.

More remarkably, the researchers also found that regrowth alone cannot explain the blistering pace at which our trees are putting on wood. By examining forest growth rates while controlling for age-related differences, the scientists determined that something else is supercharging growth.

And while the study did not directly answer what that something is, the authors highlighted one likely explanation: Trees are gobbling up some of the excess carbon dioxide we’re putting into the atmosphere. Essentially, by burning fossil fuels in our cars, buildings and factories, we are fertilizing nature. And nature is responding.

Many studies have speculated about carbon fertilization using computer models, experiments and theory. It’s clear that all things being equal, plant leaves respond to higher carbon dioxide levels by ramping up photosynthesis (the biochemical process plants use to turn carbon dioxide into sugars), which could cause plants to grow faster and ultimately store more carbon.

But in nature, many things can affect how fast trees grow. Experiments have pumped high levels of carbon dioxide into young forests and found that trees initially grew faster than in unfertilized control plots but eventually leveled off, presumably as nutrient limitations or other factors throttled trees’ growth rates.

The new study is among the first to provide clear evidence that real-world forests over a vast landscape are indeed able to use the extra CO2 to bulk up. And our trees are feasting on carbon dioxide, those in other places with moderate temperatures and ample moisture, such as northern Europe and eastern Asia, likely are too.

*********

Now, “carbon fertilization” might sound like a wonky scientific abstraction. But for the 180 million of us who live in this part of the world, it has had real, measurable benefits. The trees in our neighborhoods and parks, and even our own yards, have grown faster than they otherwise would have. That means more shade, more storm protection, more wildlife habitat — and, not least of all, more wood. We have all benefited, in multiple ways.

Now, on to the western US:

In the western U.S., unfortunately, the data tell a different story. Forests there are growing less and less robustly, as heat and drought limit trees’ ability to benefit from high CO2 levels. (Interestingly, the Forest Service has reported this for years based on FIA data, but I suspect their reports rarely get read.)

The plight of western forests has gotten plenty of coverage, so I won’t dwell on it here except to note that the fact that some forests are benefiting from high CO2 levels does not mean we can simply assume that all forests will — and certainly does not suggest we don’t need to worry about climate change.

I asked Lichstein and his colleague Aaron Hogan what implications their research has for natural climate solutions — the idea that natural ecosystems like forests can soak up some of the carbon dioxide we humans emit by burning fossil fuels. Their answer, perhaps surprisingly, was not much. In fact, they said that at the global scale, the strength of the carbon fertilization effect is probably exaggerated in most of the computer models scientists use to forecast climate trends.

In other words, as future warming stresses forests, they will probably absorb a smaller and smaller fraction of our total carbon dioxide emissions. Right now that fraction is one quarter, so the strength of the carbon sink diminishes, we could be in real trouble.

This aligns with my view, based on years of reporting on forest science, that at a broad scale, forests and other ecosystems are probably already doing about as much as we can hope for to slow climate change. The idea that we’re going to jam tons of additional carbon into trees or soil strikes me as more aspirational than realistic.

It seems to me that there are three things going on here (which may be investigated somewhere, hopefully commenters will point this out). 1. Western forests are very different from each other, and some (like the Black Hills) are supposed to be getting wetter based on climate models. 2. Fire suppression allowed many more trees (increased density over time) in some spots, so competition for water would cause them to grow more slowly. 3. After cutting trees for railroads, firewood, and lumber in various places, at various times from in the 1800s and 1900’s trees are growing back and age might be an important reason that growth slows down. I don’t know how well the study adjusted for those factors.

It’s also worth noting that most of these fast-growing forests are not in parks or preserves, but on private land. That means they can legally be cut down, but it also means that millions of people have a stake in them. The public ownership that’s more common in the West — and that’s often assumed to be more protective — can also be more neglectful, especially when governments don’t have the resources to properly care for vast tracts they’ve been tasked to manage.

While private ownership is not a panacea either, when a lot of people live among forests, there are a lot of people with reasons to keep an eye on them and care for them. Technologically speaking, we could easily cut down every tree in the eastern U.S. — as far fewer, less technologically advanced people once did. Yet instead, we’ve allowed them to grow at the same time that our own population has grown.

This pushes strongly against what I would describe against the prevailing narrative that people are simply bad for trees. This kind of simplification has even been embraced by the august New Yorker, a publication I would expect to do better.

It’s time to ditch simplistic morality tales for a more nuanced and reality-based view of the relationship between trees and humans. After all, we need trees to thrive in places where people actually live. I’ve argued previously that the densely populated Mid-Atlantic could be a climate refuge, in part because our cities and towns are embedded within what, so far at least, appear to be remarkably climate-resilient forests. The new study suggests the same might be said about much of the eastern U.S.

from Sharon “…forests and other ecosystems are probably already doing about as much as we can hope for to slow climate change. The idea that we’re going to jam tons of additional carbon into trees or soil strikes me as more aspirational than realistic.”

Catherine Mater recently competed a study of forest carbon for OR in the years following NW Forest Plan, and reached an entirely different conclusion. Federal forests went from carbon source to sink, with dramatic speed, after general cessation of CCing mature and old growth forests and reduced harvest levels. Pvt industrial lands basically registered no change.

Didn’t exactly “strike her” as much as result from methodical analysis.

That wasn’t me, that was the reporter Gabe. I don’t necessarily agree with him because I see so many acres post-fire where trees could be planted. Of course, some will run models and say that they will all die, so we don’t know.

I think that there have been many analyses for forest carbon on different kinds of sites with different conclusions. As much as I hate repeating myself on this, the forests and people of western Oregon are not the final word on US forests, even US western federal forests. So I’ll start a new post and we can discuss some of the studies and why that is the case.

I have not read the original paper that the article was based on but I am very curious if they looked at mortality rates or just growth rates. Every time I visit back east I see forests that are a disaster. Gross overpopulation of deer decimate regeneration leaving an understory of barberry and buckthorn. Mature trees are being ravaged by Chestnut blight, Hemlock woolly adelgid, Dutch elm disease, Emerald ash borer, Gypsy moth, Beech bark disease, and migrating southern pine beetles. I might just have a skewed sample but they don’t seem to be thriving.

I’ll do some digging and ask around.. good question!

Thx for clarification SF. It “strikes me” that much of US mature and old-growth forests have been lost over time. Yet our forests, in aggregate, remain a powerful carbon sink. Federal forests in particular could address climate change issues with an effective response to Biden’s Ex Order 14072 by restoring much of MOG that’s been lost. Yet – surprisingly – the FS proposal makes no mention of mature forests.

We’ll start another post on the carbon sink.. but what exactly would you like to see for mature forests, and how do you define “mature”?

longish answer coming soon…

Jim, if you want to do a post and start another thread, just send it to me!

I’ll leave that to you. Here’s to kicking the hornet’s nest…

My view is that FS has engaged in 3 big “eras”: 1) Custodial (from agency creation to WWII) – getting a grip on uncontrolled forces ravaging the public domain (grazing and logging notably) 2) Utilitarian (WWII -1990) – the BIG response to timber demand, characterized by asking virtually every NF to turn out timber, and fostering emergence of a “new” timber industry sector that owned no land. 3) Ecosystem Mgmt (or maybe just ??) (1990- present) – as yet ill-defined, although post-owl crisis NW Forest Plan gave it a start.

Climate change emerged since 90’s as a major driver of forest policy debates, noted by a glacial response from FS with respect to forest carbon and now MOG forests. Similar to the FS response to spotted owl, the FS is seemingly doing as little as possible to move the needle, let alone embrace a progressive, conservation-oriented vision, consistent with the enormity of the climate challenges we face. My recent reading of Fire Weather (about Alberta’s Ft. McMurray fires, and so much more) only reinforces my fervor about this lost opportunity.

Mature forests sit squarely in the midst of the quagmire. Simply put, are M forests seen as the last bastion of commercial forestry, or the basis for expanding OG character broadly on federal forests everywhere? It seems odd, but not surprising. that the recent OG policy proposal omitted M forests entirely. I’d say the FS tipped their hand.

Notably, NW Forest Plan struck a bargain with pvt industrial lands – feds will bear the brunt of endangered spp protection so they can continue their harmful, profit-driven practices. Now we need a similar bargain – feds bear the brunt of climate change mitigation so pvt industry can provide the bulk of wood products. This is not to say commercial logging stops on NF lands, only that it focus largely on smaller, younger timber than MOG.