[This Post includes two JPEG Tables. Any one who can help correct, fill, and/or map this data would be very much appreciated.]

About 15 years ago, forester Bruce Courtwright became very concerned about increasing wildfires and wildfire risks to the communities of northern California, so he helped gather a number of other wildfire experts to collectively address the problem. This group eventually became known as the National Wildfire Institute (NWI) and was in the process of becoming more formal a few years ago, when Bruce became ill and died. Without a leader or formal organization, members have remained active, mostly via informal email discussions, local meetings, phone calls, and proposals. Promotions of Michael Rain’s “Call to Action” and Jim Petersen’s “First, Put Out the Fire!” have been key group efforts to effect needed change as to how the USFS can better manage its wildfires and forestlands — and including immediate snag salvage and site preparation moving forward, followed by better reforestation planning and forest maintenance strategies for future generations.

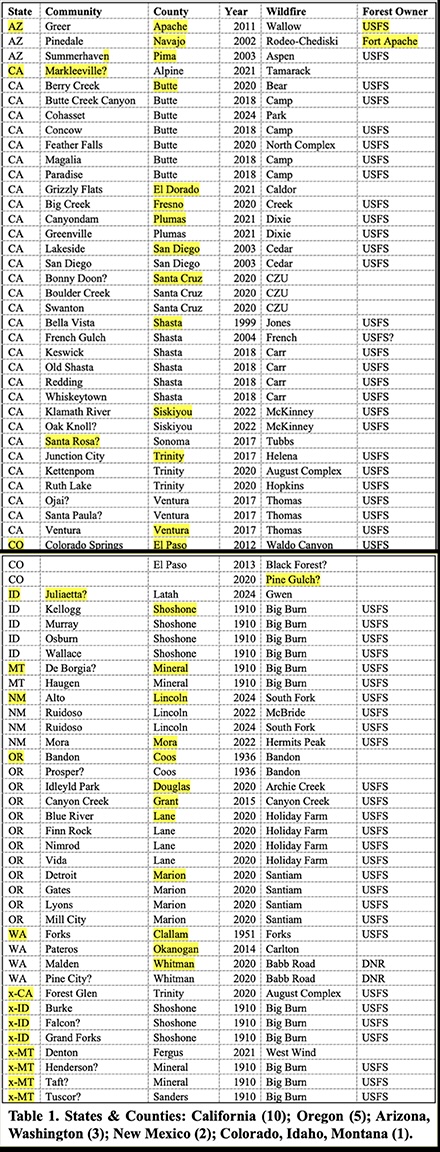

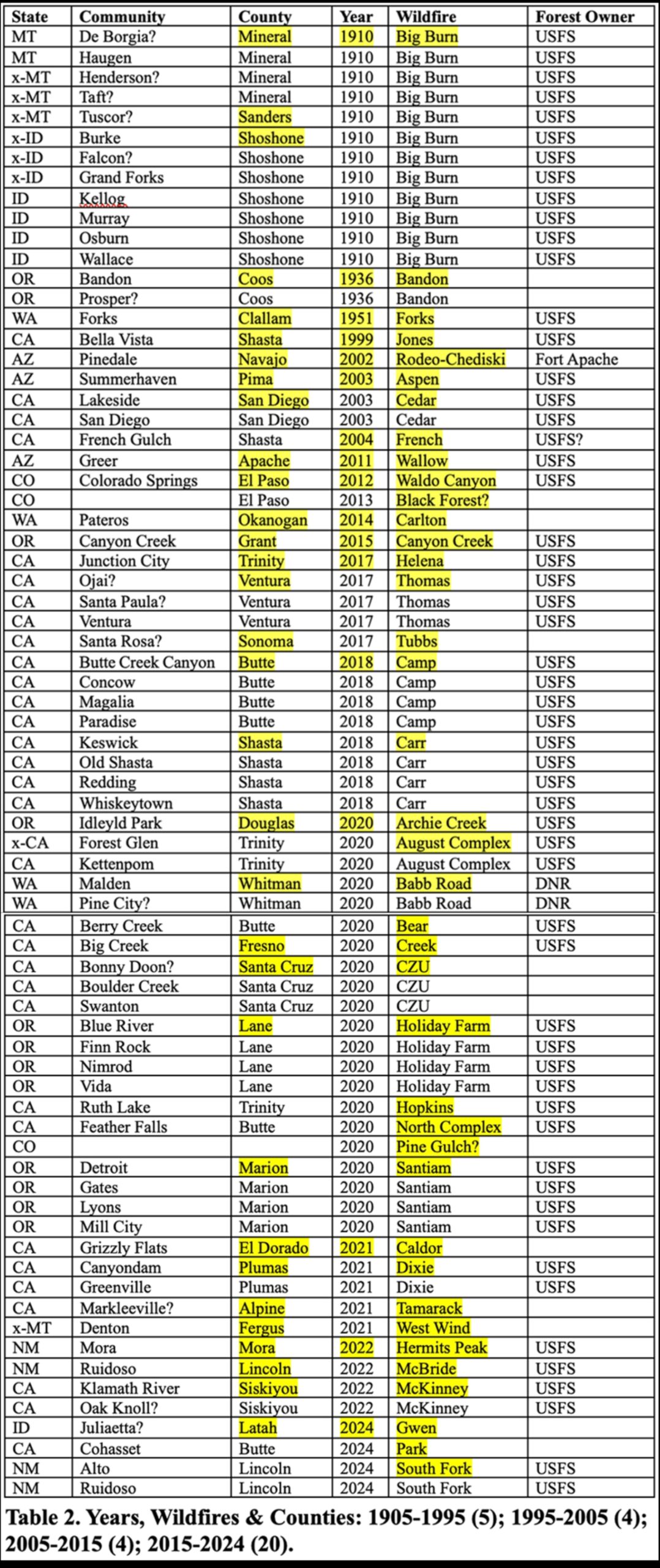

These efforts continue, and were recently expanded with Rob DeHarpport’s concern over the increasing number of rural towns being damaged or destroyed in forest fires. That insight has led to me, Petersen, Lake Tahoe writer Dana Tibbitts, and NWI members such as Roger Jaegel, Bill Derr, and Bill Dennison, to begin assembling a list of affected communities in order to develop a baseline for further analysis. An Excel file was established for this purpose and our initial findings — summarized in the following two tables — were startling. So far, more than 70 communities are listed, beginning in 1905, most such fires have occurred in the past 10 years, and almost all of them were started on National Forests, and most of those are in the legal range of spotted owls and subjected to the NWFP.

Initially the listing started with the Peshtigo and Great Michigan forest fires of 1871, but from the outset the focus has been on towns most recently burned and rebuilding, and on towns currently threatened by wildfire risks on adjacent and nearby forestlands. There was no attempt to list towns or named communities that were subjected to grass or shrubland fires, or included rural subdivisions or mobile home or RV parks — just forest fires, and an arbitrary division of at least 30 structures burned; or 50% of a community’s structures if it had less than 60 buildings. We were pretty shocked at how recent most of the fires were, and also that they were almost entirely related to USFS lands, so we made 1905 the logical starting point. All indications are that the September 2020 Fires were at least as destructive, if not as deadly, as the historic 1871 and 1910 Fires.

Table 1 is a listing of the burned communities arranged by state and county. We fully expect these numbers to increase with midwest and south histories, as well as the 1963 Pine Barren Fires in New Jersey. The “x-” States are those showing towns that were burned and never rebuilt — the 1910 Railroad towns are most of these. The “?” Towns are those that may have escaped damage or weren’t related to a forest fire and may need to be removed. Any help with blanks, corrections, or additions appreciated!

Burning down the house: Unilateral intentional wildfire use is killing people and burning private property.

Remanding lands in the public domain to the tribal communities from whom they were seized can’t happen soon enough.

Interesting.. Thanks, Bob and everyone!

Question: what does the yellow highlighter mean?

I am no expert, but I have some idea of the geography. Given that ID, NM, AZ and MT are not in the NWFP, and the Sierra is not (it does have CASPO, but that’s not the same), I have trouble thinking that “most” are within NWFP territory. Maybe it you had a separate table for the last 10 or 20 years, that would be helpful?

Not to harp on this, but it would be good to know how many were human caused versus natural ignition. When I think of NWFP and CASPO terrain, I think of good growing conditions, and dense vegetation, which could lead in and of itself to high fuel loading, under the fire suppression policies of the past century or so.

I think the idea of interviewing communities with those five questions is good. Maybe someone knows if this kind of research has been done? I wonder whether it would fit JFSP (Joint Fire Sciences Program)?

Thanks Sharon:

The highlights show the separate counties and states on Table 1, and the individual years and fires on Table 2.

These are meant to include the entire US to put these events in context — the NWFP entries emerged from that whole. More than 1/2 of the fires listed since 1994 are in the NWFP. There was no effort to focus on that result, it just developed.

I have never had too much interest in determining whether a human smoker, electricity user, or arsonist started a fire — or whether it was lightning or volcano — only how the fuels responded under the existing conditions after ignition. People are almost as hard to control as the weather, but fuels are usually manageable. I don’t think this is a “fire suppression” result so much as abandonment.

Nice work with gathering and compiling this data, Bob. I think the human vs natural cause ignitions would be important to know if there are conclusions being drawn about changes in forest management because of the probable increase in the number of humans in the forest over time. Additionally, humans have a habit of starting fires during dry/windy periods whereas natural ignitions often start with more humid/wet conditions. This adds a potential confounding factor to viewing this as a forest management issue. Another possible factor, of course, is the expansion and increasing density of human developments.

Thanks Mike: Some of the other NWI folks, working with Roger Jaegel, Bill Derr, and others, are also compiling databases of communities in which their watershed has been impacted by forest fires, and communities which have not yet been burned in a wildfire but are under immediate threat due to management of adjacent and nearby forestlands. The focus on local and county media, elected officials, and long-term residents is a key strategy with all three compilations.

We agree on what is “important to know,” and hopefully these proposed studies can develop that information in addition to charting safer and more pleasant futures for these families and communities — and for the forests and wildlife they share.

My experience is that humans start fires everyday everywhere, no matter the weather conditions. If they do it in a ship at sea, no problem; but if the environment is loaded with highly flammable fuels, perhaps stretching for miles, then the weather is a lot more important. Western Oregon is the location of some the most catastrophic wildfires in history, and the Klamath-Siskiyous and western Cascades get thousands of dry lightning strikes causing wildfires every fire season; but the Coast Range gets very little lightning ever — and then mostly accompanied by heavy rains — so nearly 100% of wildfires are human caused — so it is more a regional problem, and the national scale of this inquiry could produce some very useful information for specific locations.

I am not sure how the Montana fires fit into all of this. If I recall correctly, the “Big Burn” communities listed in Montana were mostly camp towns associated with railroad construction, not permanent communities. Also, the 2021 fire that affected Denton, Montana was not a forest fire. Denton is surrounded by agricultural fields and the nearest FS land is 25 miles away. Hard to blame that one on the FS.

Thanks Anonymous: The railroad towns have an “x-” next to them for that reason — explained in the text. Appreciate the insight on Denton — that verifies the “x-” on its entry as well and will remove from database. This is a work in progress, so feedback is helpful.

1. Markleyville was not burned down. In fact, the efforts of USFS/CAL FIRE firefighters saved the town.

2. Berry Creek was impacted by fire that ran through industrial timberland that is heavily managed, in less than 12 hours, catastrophically.

3. Concow in the 2018 Camp Fire was rife with properties where the owners refused to take any kind of defensible space/fuel reduction work, namely due to the proliferance of illegal pot farms in the area (where they wanted the brush and trees to hide them).

4. San Diego is a rural community?

5. Bonny Doon, and the CZU Complex, was 100% non-federal land. The fault of poor firefighting, if that is the argument, is 100% on CAL FIRE, and in an area rife with heavily managed forests.

6. Old Shasta, Redding, Whiskeytown, and Keswick are not in commerical coniferous forest. Redding is a CITY of >90k. The others are suburbs of it. The fuel from the Carr fire was driven by manzanita, non-commercial trees like grey pines, and a lack of effort of the landowners to ever do anything related to defensible space. Further, the fire originated from NPS lands, went to BLM lands, then went to private lands where it wreaked havoc, all during an exceptional heat wave. The USFS land, and subsequent industrial timberland, impacts were afterthought effects of the fire.

7. Santa Rosa is a far, far, far cry from a small rural town. It is a large city. Further, This lists does not even have the Atlas Fire, which was actually driven in part by fire within confier forests, but mainly impacted million dollar mansions.

8. Ojai, Santa Paula, and Ventura had little to do with USFS and, and in fact were driven by manzanita burning, and further, are large cities with exceptional wealth, home to thriving yoga communities and Hollywood actors.

9. Kettenpom and Ruth Lake had few to any year round residents. They are glorified hunting cabins.

10. 1951, Forks – go read The Final Forest and learn some history.

11. Pateros and Malden were burned by grass, coming from non-USFS land.

….is this list to point out an agenda, or facts from a scientist?

You could actually do this scientifically with Census data, fire perimeters, vegetation types, and more data in GIS, but this looks more like a “Back in my day” kind of list.

Hi Anon: Thank you very much for this information. I would guess that is a rhetorical question from you at the end, and intended to be insulting. Very brave for a coward hiding behind a fake identity. Lots of the “Anonymous” posters are civil, respectful, ask good questions, and offer useful information. I suggest having enough huevos to use your real name when being snarky or publicly questioning someone’s credibility.

You do offer useful information, though, and I’d like to follow up. Here are my responses:

1. Thanks. We’ll remove it from this list and consider adding it to the others.

2. That’s interesting. Can you name the industrial landowner(s)? Was NF land involved? We could answer those questions easy enough, but with 60+ communities and proposals just being developed, more specific information would be very helpful at this juncture.

3. And?

4. Neither is Redding, so they are outliers. “Rural” is a generality, but the criteria was forest fires that enter a named community and burn at least 30 structures. No size limit, except minimum 50% burn requirement for communities with less than 60 structures.

5. More specific details?

6. So NPS origin? Redding is answered above.

7. So we should add the Atlas Fire? Year and affected town(s)?

8. We’re not tracking wealth, yoga, Hollywood, or personal values, so more information on your “little to do” assessment would be helpful.

9. Are they named communities?

10. Go read it yourself. I planted trees out of Forks as a contractor in the early 1980s and may know its history — and certainly older people and historical taverns — better than you. You seem to have an attitude — is that why you operate in secret?

11. I will put a “?” next to their names until better information develops.

Thanks for this help. Answer to your questions: 1) No, it is to look for solutions; and 2) scientists don’t do “facts” — we ask questions and look for possible answers. You’re welcome. Now grow up, get out of the basement, and seek some meaningful employment is my advice. And have enough spine to sign your real name when you publicly state your biases and opinions regarding real people and communities.

Pateros was not burned down because of “grass”. This from a Californian more than likely who has no clue about what happens in WA and probably has never been here. DNR is to blame for the Carlton Fire. First of all while Goldmark was the DNR Commissioner he neglected all of the DNR lands and did zero fire prevention, mitigation and did not work with other agencies. We had 4 to 5 fires from a lightning storm both on DNR and private land that they did not put out. They lied to locals and land owners that were there putting the fires out that they need to leave as they have it under control. Land owners came back the next day… no trucks and no crews and fire growing larger. Several days later a wind event carried the fires and eventually combined them. Various fuels. All crews were told to stand down. No one was fighting the fires. Local landowners were getting arrested for bulldozing in an attempt to make firelines and save properties. The agencies were sitting around a round table in Twisp trying to figure out what to do. THAT is why Pateros burned down. INACTION!!! Fire was in Pateros while they were meeting 50 miles away. All crews standing down!! No one doing structure protection!! We lost our home we had just bought and know exactly why!! INACTION!! Gebbers finally got sick and tired of what was going on and got their crews and dozers out and fought the fire for them more than likely saving the town of Brewster! Everyone here knows what happened and how it happened. Now… we have a different set of rules for the area. Joel Kretz worked hard in Olympia working alongside of Hilary Franz and we have not only the Samaritan Law set up to where ANYONE CAN PUT OUT A FIRE ANYWHERE but also UNIFIED COMMAND between the USFS, DNR and local districts!! And Hilary has been doing mitigation for years now on DNR lands trying to undo the Goldmark reign neglect for decades!!

Thanks Dagmar: I am sorry about your loss and experience, but these are the exact types of stories that we are trying to learn: what could have been done to prevent the fire, and what has been done to prevent a reoccurrence. A lesson for other communities and forest managers to consider.

I added “DNR” to the “Forest Owner” column for Pateros, and it joins the 2020 Babb Road Fire as the lone entries in that category (and yes, I know that citizens technically own these properties and not government agencies).

It is amazing how important the DNR Commissioner position really is. Our forest are a lot healthier because of the proactive work they have done under Hilary’s leadership. The FS also has joined in and now we also have Trex teams that are mostly native and they teach about wildfire while doing prescribed burning. The Colville’s, Selkirk’s and other tribes are joining in the prescribed burning each fall to spring. The USFS uses fires implementing prescribed burning in the plans around the areas of said fires under that gov contract. While prescribed burning can go awry as on the Pioneer Fire this year above Lake Chelan and they brought the fire down to Stehekin at the head of the lake… some of the area will benefit and may not be so prone to catching fire from lightning strikes. They have also been doing road improvements under the the fire contract. These past 2 months there is no fire anymore… however they have been doing all the roads on the Sawtooth within the Pioneer Fire jurisdiction and improving them. Leaving them open incl. the old opened dozer lines abandoning the “endless forest” concept. At least in this area and our mntns. here. So now we will have good access to the Sawtooth where there are roads and some off roads for future fires.

Not sure the source of this data, but as a resident of Shasta County the town of Whiskeytown has not existed since it was inundated by the construction of Whiskeytown resoivoir in 1964. It definatly did not burn in the Carr Fire, as it did not exist in 2018. Did someone pull these town locations from historic USGS maps?

Thanks Big Pondo: This is a “first cut” at developing a list that was compiled by several individuals from numerous sources and a key reason I posted here — for review and updating with corrections and additions. Like it says in the text.

According to the National Park Service: “Three firefighters died, four civilians died, and over 1,000 homes and buildings were destroyed. With over 97 percent of Whiskeytown burned and over 100 structures (buildings, boats, etc.) within the park destroyed, the Carr Fire was the most destructive fire in the history of the National Park System.”

Apparently, “Whiskeytown” is now short-hand for the “Whiskeytown National Recreation Area”: https://www.nps.gov/whis/learn/news/carrfire.htm

Yep, the Carr fire was felt by all in Shasta county. Like another poster above mentioned the run into Redding occurred mainly on NPS and BLM land above French Gulch. It also jumped the Sacramento River, which illustrates that this was a fire driven more by extreme weather than just fuels alone.

I’ll all for giving the FS their lumps, but we can’t really hang this one on them.

Hi Big Pondo: My family moved to Redding in the 1960s before relocating to Texas, but I still have a niece and grand nephew who live there, and I think had to evacuate for that fire. It is amazing how far a fire can spot in advance — the 1902 Yacolt Fire and the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire both crossed the Columbia River where it is more than a mile wide. Pitchy snags left as “critical habitat” can operate as giant Roman candles during a wildfire and cast hundreds of flaming embers more than a mile in advance and are able to blow burning limbs thousands of feet into the air. The fact is that major wildfires often create their own “extreme weather,” including hurricane-force winds and thunderstorms with rain.

I hope their home was spared Bob, members of my family were evacuated as well.

Thanks to all who have contributed to this discussion and to Bob for starting it. I’d like to think that this is a learning journey and we can all learn from each other without questioning motives, etc.

In fact it reminds me of “joint fact-finding” an environmental conflict resolution technique

https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/conflict-resolution/dispute-resolution-through-joint-fact-finding/

It also reminds me of the power of truly listening to others and their experiences.

“Perhaps one of the most precious and powerful gifts we can give another person is to really listen to them, to listen with quiet, fascinated attention, with our whole being, fully present. ”

https://cac.org/daily-meditations/the-gift-of-deep-listening-2022-07-27/

Thanks Sharon: This has been an excellent forum through the years for meaningful discussions, article reviews, and “joint fact-finding” in regards to forest management in general, and US Forest Service in particular.

One of the surprising things for me with this post has been the lack of potential feedback regarding southern, northeastern, and midwestern towns that have burned in forest fires in the past 120 years. I’m personally unfamiliar with the forests and their histories for those regions, but I figured other readers and commenters might be helpful in those regards — I know there are a lot of mill towns and tree farms east of the Rockies, but I’m unaware of any major forest fires that have burned towns since Peshtigo, and possibly excepting the 1963 Pine Barren Fires in New Jersey.

It is hard to imagine that this pattern will remain this prominent, but if it does then it is really remarkable how recently these events seemed to multiply, and how such a significant percentage are associated with National Forest wildfires.

If this is actually a fairly

The last six words appear to have been an intended sentence at some point. My proof-reader is not getting any better with age, and he refuses to retire.

The citizens of Gatlinburg, TN, would remind readers of the 2016 Chimney Tops 2 fire that killed 14 and destroyed 2,460 structures.

Thanks Andy: This link also led to the Maine “Great Fires” of 1947, which apparently began in towns and spread to forests and then affected other towns. The Tennessee fires seem to be NPS-related, and so far I’m assuming the Maine fires were on private lands. Until more is learned, it still seems remarkable that such a series of USFS forest fires have been entering towns in the past 10 years — and mostly in communities directly affected by the NWFP.