Last February I posted a somewhat lengthy discussion of lodgepole pine bug and fire history that included several quotes from John Leiberg’s 1899 report titled “Cascade Range Forest Reserve from Township 28 South to Township 37 South, Inclusive, Together With the Ashland Forest Reserve and Forest Regions from Township 28 South to Township 41 South, Inclusive, and from Range 2 West to Range 14 East, Willamette Meridian, Inclusive”: https://forestpolicypub.com/2013/02/28/lodgepole-pine-ecology-1899-2013/

A more comprehensive selection of his observations in this report can be found here: http://www.orww.org/History/SW_Oregon/References/Leiberg_1899/

Several of these quotes were also posted as a Comment about a week ago, but WordPress won’t let me search those files or list more than 18 of my past comments for some reason, so I am reposting them here, based on current discussions of wet vs. dry forests, natural fire regimes, and wildfire severity patterns and history.

Leiberg was a Swedish immigrant who did much of his botanical field work from his base near Lake Pend Oreille, in Idaho Territory, including the 19th and 20th annual reports of the US Geological Survey, which encompassed most (or all) of the current Bitterroot National Forest. He was meticulous in his observations, including counting the tree rings of several tree species at small sawmills that had just entered the region (“virgin forests”), and using land surveys, photography and personal interviews to build detailed maps and tables for several different forested areas in the western US, mostly in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Nevada, Montana, and Minnesota.

I believe him to be one of the very best forest scientists of his era for these regions, but his work has been sadly neglected — likely beginning with the politics surrounding the formation of the National Forests in 1906 and the transfer of the Forest Reserves for the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture. It was to Pinchot’s advantage to ignore Leiberg’s work because it directly contradicted his assertions that the federal reserves were not being properly studied or managed. Leiberg died in Leaburg, Oregon (near Eugene) in 1913.

I would be very interested in the thoughts of other Commenters on this blog regarding the following quotes:

(p. 245) The duration of the forest type is indefinite. While undoubtedly subject to evolutionary changes, its modifications or transitions to other types are so slow as to be quite imperceptible to us. Not so with subtypes, They frequently change, sometimes two or three times in a generation. Forest fires are fertile causes for inducing such rapid changes. But even when left undisturbed a subtype rarely persists in any particular locality for more than 250 or 300 years. Such at least is the rule on the eastern and immediate western slope of the Cascades and in the basins between the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains. The only exception to this rule in the region named that is known to me occurs in pure yellow-pine and western-juniper growths.

(p. 248) But the open character of the yellow-pine type of forest anywhere in the region examined is due to frequently repeated forest fires more than to any other cause.

(p. 249) The forest floor in the type is covered with a thin layer of humus consisting entirely of decaying pine needles, or it is entirely bare. The latter condition is very prevalent east of the Cascades, where large areas are annually overrun by fire. But even on the western side of the range, where the humus covering is most conspicuous, it is never more than a fraction of an inch in thickness, just enough to supply the requisite material for the spread of forest fires.

(p. 268) In other places fires have destroyed a certain percentage of the forest. The damage may vary from 10 to 60 per cent or higher. The destruction has not been all in one place or body. The fire has run through the forest for miles, burning a tree or group of trees here and there.

(p. 274) The age of the timber utilized in sawmill consumption varies from 100 to 350 years. Most of the yellow pine falls below 175 years; the higher limit is reached chiefly in the sugar pine. Most of the sugar pine in the region is of great and mature age. Comparatively little red fir is sawn. It varies in age from 100 to 500 years, and some of the very large individuals seen were doubtless even older. The noble fir and white pine of mill-timber size varies in age from 100 to 350 years, most of it falling below 180 years. The alpine hemlock of mill size runs from 80 to 250 years, 120 to 140 years representing the age of the bulk of the standard growth. The white fir, with sufficient clear trunk development to come within the limit of these estimates, varies in age from 75 to 120 years.

(p. 277) The aspect of the forest, its composition, the absence of any large tracts of solid old-growth of the species less capable of resisting fire, and the occurrence of veteran trees of red fir, noble fir, white pine, alpine hemlock, etc., singly or in small groups scattered through stands of very different species, indicate without any doubt the prevalence of widespread fires throughout this region long before the coming of the white man. But, on the other hand, the great diversity in the age of such stands as shown clearly their origin as reforestations after fires, proves that the fires during the Indian occupancy were not of such frequent occurrence nor of such magnitude as they have been since the advent of the white man.

(p. 277) The age of the burns chargeable to the era of Indian occupancy can not in most cases be traced back more than one hundred and fifty years. Between that time and the time of the white man’s ascendancy, or, between the years 1750 and 1855, small and circumscribed fires evidently were of frequent occurrence. There were some large ones. Thus, in T. 37 S., R. 5 E., occurs a growth of white fir nearly 75 per cent pure covering between 4,000 and 5,000 acres. It is an even-aged stand 100 years old and is clearly a reforestation after a fire which destroyed an old growth of red fir one hundred and five or one hundred and ten years ago. A similar tract occurs in T. 36 S., R. 5 E., only that here the reforestation is white pine instead of white fir.

(p. 277) The largest burns directly chargeable to the Indian occupancy are in Ts. 30 and 31 S., Rs. 8 and 9 E. In addition to being the largest, they are likewise the most ancient. The burns cover upward of 60,000 acres, all but 1,000 or 1,100 acres being in a solid block. This tract appears to have been systematically burned by the Indians during the past three centuries [ca. 1600 to 1855]. Remains of three forests are distinctly traceable in the charred fragments of timber which here and there litter the ground.

(p. 278) Along the summits of the Cascades from Crater Lake to Mount Pitt are very many even-aged stands of alpine hemlock 200 to 300 years old. These even-aged stands may represent reforestations after ancient fires dating back two hundred and fifty to four hundred years, but there is no certainty on this point.

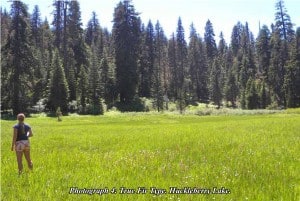

(p. 278) It is not possible to state with any degree of certainty the Indian’s reasons for firing the forest. Their object in burning the forest at high elevations on the Cascades may have been to provide a growth of grass near their favorite camping places, or to promote the growth of huckleberry brush and blackberry brambles, which often, after fires, cover the ground with a luxuriant and, to the Indian, very valuable and desirable growth. The chief purpose of the fires at middle elevations and on the plains or levels probably was to keep down the underbrush in the forest and facilitate hunting.

(pp. 282-283) There is little doubt that a very large proportion of the many rocky level tracts which occur east of the Cascades in the region under consideration are wholly due, as to the character of their present surface, to frequently repeated fires. The pumice originally laid down at the bottoms of shallow lakes would be evenly spread out. As the lakes were being gradually drained thick masses of marsh vegetation would preserve the pumice surface from wastage. The marsh vegetation was finally supplanted by forest; then man came on the scene and with fire as an ally made some profound changes. The entire series of phenomena here detailed, not omitting the part played by fire, are in full operation at the present time in the region bordering Klamath Marsh, and in various other localities, such as Sycan Marsh and tracts bordering the Klamath lakes.

(p. 288) These grassed-over places are, and have been, of commercial importance since the upper plateaus and summits of the Cascades began to be utilized as sheep pastures. All of these pastures and meadows which owe their origins to fires are merely temporary affairs. If suffered to remain undisturbed by further fires they will return to forest cover. Around Diamond and Crater lakes the grassy places are slowly giving way to stands of lodgepole pine as the primary reforestation. On the lava plateaus flanking the crest of the range in Ts. 34 and 35 S., R. 5 E., grassy places created by fires before the advent of the white man have, in course of time, become covered with thick stands of lodgepole pine, now mature and giving way to stands of noble fir and alpine hemlock.

p. 290-291) The custom of the Indians of peeling the yellow pine at certain seasons of the year to obtain the cambium layer which they use for food, is in some localities a fruitful contributory cause toward destruction of the yellow pine by fire. They do not carry the peeling process far enough to girdle the tree, but they remove a large enough piece of bark to make a gaping wound which never heals over and which furnishes an excellent entrance for fire. Throughout the forests of the Klamath reservation trees barked in this manner are very common. Along the eastern margin of Klamath marsh they are found by the thousands.

(p. 298) The southern and central portions are covered with stands of lodgepole pine, all reforestations after fires and representative of all ages of burns from one hundred fifty years ago [ca. 1750] up to the present time [1899]. There is no portion of these or the heavier stands of alpine hemlock and noble fir in the northern sections of the township that have not been visited by fire within the past forty-five years [since 1855]. Reforestations consist wholly of lodgepole pine as the first growth. In some places on warm southern declivities brush growth comes in after fires. In other localities a grass and sedge sward covers the ground. It is clearly evident that many of the fires have been set for the purpose of promoting these grass growths and enlarging the possible sheep range. It is also noticeable that wherever fires have been kept down for four or five years there is gradual return to forest and a disappearance of the grass.

(p. 305) This region [T. 29 S., R. 5 E.] was burned periodically during the Indian occupancy, as the many different ages represented in the lodgepole pine stands prove. But when the white man came into the region the areas in this particular township was covered with a uniform stand of the species. During the past forty or forty-five years [1855-1899] the timber has been burned in many locations and the subsequent reforestations have again been burned. The region is too high in altitude to permit the growth of much brush. After a fire one of three things happens: either lodgepole pine comes in as the first forest growth, or grasses and sedges form a thin, interrupted sward, or the ground remains bare of all vegetation. It is impossible to predict beforehand which one of the three phases will appear.

(p. 395) The forest is of the alpine-hemlock type throughout [T. 35 S., R. 5 E.] . Fires of modern origin have ravaged it extensively. The great burns which cover the eastern areas of the adjoining township and wrought great havoc among what must have been heavy stands of noble fir. The forests in the eastern areas have suffered no less, and there are scant signs of reforestation. Most of the young growth now standing is overwhelmingly composed of lodgepole pine. The bottom and eastern slopes of the South Fork Canyon have escaped fairly well and carry a forest in a state of tolerably good preservation. Much of it has not experienced a fire for 300 or 400 years, and in consequence it contains a vast amount of litter, consisting chiefly of the original lodgepole pine growth which followed a fire that occurred between three and four centuries ago [ca. 1500 to ca. 1600]. The lodgepole pine has had time to mature, die, and fall down, and a new forest 150 years old has taken its place since that time.

(p. 457) The Pokegama Lumber Company operates here, sending the logs to their mills at Klamathon, on the southern Pacific Railroad, by way of the Klamath River. They cut pine exclusively, and cut all pine clean as they go, leaving great accumulations of debris behind them for future fires. They take all trees far into the crown, trimming off the limbs and making the last cut on a basis of 7 to 8 inches in diameter at the small end. In consequence they realize about 40 per cent higher yield than the customary cruisers’ estimates provide for.