Links provide more information

On April 19, the Council on Environmental Quality finalized the first of two phases of rulemaking to replace the Trump administration’s 2020 rewrite of NEPA procedures. The Phase I Regulations address three primary issues: (1) how to prepare a purpose and need statement in NEPA documentation; (2) the scope of agency-specific NEPA implementation regulations; and (3) the definition of “effects” and “cumulative impacts.” (The article includes a link to the new rule.) The second phase is expected to be broader. Five lawsuits currently pending on the Trump rule will continue. Litigation also continues against the Forest Service NEPA regulations adopted in 2020.

On May 5, eight conservation groups notified the Custer Gallatin National Forest and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service of their intent to sue over the East Paradise Range Allotment Management Plan, which authorized grazing on three of the six allotments described in the plan. The notice states that the agencies failed to take a “hard look” at the plan’s impacts on grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (9th Cir.)

On May 12, the 9th Circuit affirmed the district court of Arizona’s decision that the Forest Service acted arbitrarily and capriciously in approving the plan of operations for the Rosemont Copper Mine on the Coronado National Forest based on its misunderstanding of Section 612 of the Surface Resources and Multiple Use Act of 1955, and on its incorrect assumption that Rosemont’s mining claims are valid under the 1812 Mining Law. (This article provides additional information.) The Copper World Mine on adjacent private land is proceeding.

Court decision in Desert Survivors v. U. S. D. I. (N.D. Cal.)

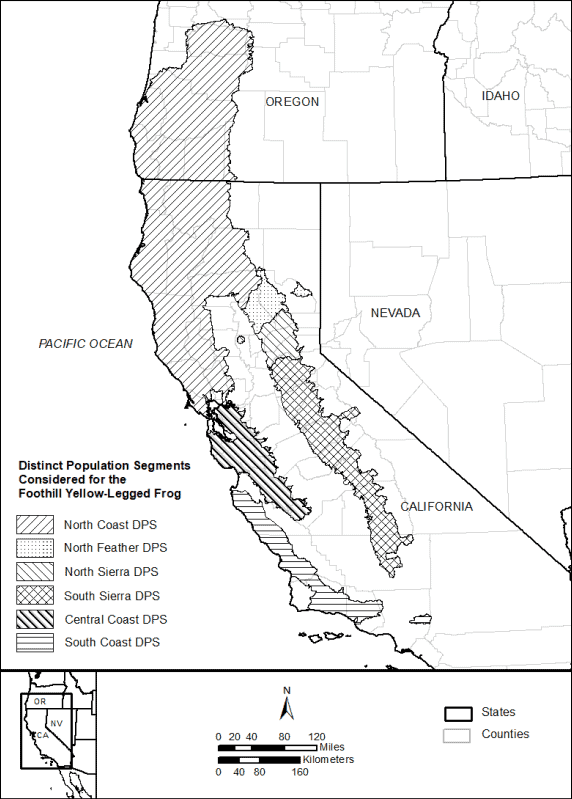

On May 16, the district court overturned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s withdrawal of a proposed Endangered Species Act listing and section 4(d) rule for the “bi-state population” of the greater sage grouse found along the California-Nevada border (including the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest). The court held that the agency failed to adequately explain their determination that the species did not warrant listing based on the available science. The court reinstated the 2013 proposal to list the species as threatened and required a new listing decision. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

New case: Friends of the Flathead River v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Mont.)

On May 16, a newly founded nonprofit filed a suit claiming the Flathead National Forest is violating the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the Forest Service Organic Act and the Administrative Procedure Act by not updating a 1985 comprehensive management plan for the Wild and Scenic River to better manage heavy use.

New case: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Mont.)

On May 17, five conservation groups filed suit against the Knotty Pine timber project on the Kootenai National Forest. The project would include roughly 3,000 acres of commercial logging as well 40 miles of road maintenance and road building. Plaintiffs allege violation of forest plan requirements to provide habitat security for grizzly bears. (An ESA claim may be added.) (A link to the complaint is at the end of this article.)

Court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. Wyo.)

On May 17, the district court upheld the Upper Green River Area Rangeland Project’s approval of continued livestock grazing on six allotments on the Bridger-Teton National Forest. The court held that the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service properly determined that 72 grizzlies could be taken as a result of grazing conflicts within 10 years without specific guidelines for age and sex. (Note: the characterization of incidental take as being a “threat” to these bears is not inappropriate as suggested here.)

Court decision in Citizens for a Healthy Community v. U. S. Department of the Interior (D. Colo.)

On May 19, the district court remanded a master development plan for oil and gas development in Colorado’s North Fork Valley. The court said the BLM and Forest Service had admitted that they did not comply with recent executive orders and other rulings that they must weigh any proposal’s contributions to greenhouse gases and climate change. (Additional background is in this article.)

Settlement in Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (D. Oregon)

On May 24, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to reconsider its decision in 2019 to reverse itself and not list the red tree vole under the Endangered Species Act. The voles are found in old-growth forests on the Oregon coast. (A link to the original complaint may be found here.)

Court decision in Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility v. National Park Service (D. D.C.)

On May 24, the district court found that the Park Service had failed to comply with NEPA when it authorized e-bikes to travel on trails and roads used by conventional bicycles without preparing an EIS or EA. However, the judge did not block their use pending NEPA compliance. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

On May 24, The Xerces Society and Center for Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for failing to properly consider harms to endangered species caused by insecticide spraying across western grasslands. The most popular insecticide, diflubenzuron, is used to control gypsy moths and pine beetles, as well as grasshoppers on rangelands. There are more than 230 listed species in the 17 states encompassing the spraying and legal challenge, ranging from bull trout to sage grouse. In Oregon, the federal government is accepting bids to spray 30,000 acres of public lands.

Court decision in Alliance for the Wild Rockies v. Gassman (D. Mont.)

On May 25, the district court enjoined the Ripley timber project (including 10,854 acres of commercial logging and 238 acres of clearcutting), on the Kootenai National Forest in a lawsuit filed by the Alliance for the Wild Rockies for failing to adequately consider the effects of associated roads on grizzly bears. There would be 13 miles of permanent roads and six miles of temporary roads, as well as maintenance or reconstruction on 93 miles of existing roads.

Court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. Mont.)

On May 26, the district court vacated the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2020 withdrawal of a proposed rule to list wolverines as threatened or endangered. In November, 2021, the FWS had filed a motion for voluntary remand of the withdrawal without vacatur. Vacating the 2020 decision means the prior proposed listing rule is in effect, and wolverines receive ESA protections as a proposed species; the agency has 18 months to submit a new listing decision. (There is a link to the opinion on this web page.)

New case: Swan View Coalition v. Haaland (D. Mont.)

On May 31, plaintiffs filed a complaint against the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service for failing to properly re-evaluate the effects of the Flathead National Forest’s revised land management plan on grizzly bears and bull trout. The re-evaluation was required by the district court in its June 2021 decision discussed here and pertains to changes in road management. (The article includes a link to the complaint.)