I’ve been wanting to hear from stakeholders involved with 2012 planning processes. Many thanks to Sam Evans for taking the time to share his experiences. I’m sure this will lead to a great discussion! In addition to the specifics of this plan, we can reflect on the overall context of the 2102 Rule, as Sam says “This is also a make-or-break moment for the planning rule. Ten years in, there are no more excuses. The rule is not in transition any more. What the rule means here, now, is what it really means.”

**********************************************************************************************************************

Better intentions; fewer commitments

The Nantahala-Pisgah Plan Revision by Sam Evans

As the 2012 planning rule approaches its tenth birthday, another early-adopter is finally nearing the finish line. What does the Nantahala-Pisgah planning process tell us about whether we’re realizing the planning rule’s potential? Here’s a short history of a long process.

Background

The contiguous Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests in western North Carolina are the heart of the Southern Appalachian mountains. Managed as a single administrative unit, these forests are the third most visited in the National Forest System, and the most visited without a ski resort. The forests here are marvelously diverse and bewilderingly complex. A short walk can take you, ecologically speaking, the entire length of the Appalachian Trail, which incidentally passes through the area on its way from Georgia to Maine.

Ecosystems repeat in small patches, with more variation and texture than stanzas in a Coltrane improvisation. A few acres here and there, riffing across the landscape. Dry, fire-adapted forests intermingle with moist Appalachian coves, which are among the most diverse ecosystems outside the tropics.

Those moist and productive cove forests also grow valuable sawtimber. And, like other productive forests with big trees, they have tempted mismanagement and abuse. The Forests have been through at least two periods of unsustainable logging, once before Forest Service acquisition, at the turn of the 20th century, and another after, in the 1980s. There is plenty of work needed to restore degraded forests’ composition, structure, and processes. Still, much of the landscape is recovering well: pockets of old growth, disturbance-sensitive species, and backcountry areas large enough to allow for natural disturbance processes to resume.

These remnant and recovering conservation values have been a source of conflict. Much more often than not, projects have created a zero-sum choice between harvest and environmental protection. The Forests’ first plan, adopted in 1987 at the height of the timber wars, was remanded by the Chief before the ink was dry in response to protests to end rampant clearcutting and protect old growth.

The 1994 amended plan fared little better. Without public support for timber production, the agency shifted its rationale, pitching rotational harvest as a way to balance age classes for the benefit of wildlife. But the timber program itself didn’t change. Old growth, rare habitats, and unroaded areas were still scheduled for rotational harvest, and the agency dutifully attempted to implement the plan at their expense.

Attempted, but without much success. While the 1994 plan amendment promised up to 3,200 acres of timber harvest annually, the agency has been able to produce just a fraction of this, with recent averages around 750 acres each year. Even at low levels of timber harvest, at least some conservation priority areas have been prescribed for even-aged harvest in most projects under the 1994 plan, and the ensuing conflicts have been a tremendous drag on efficiency, resulting in wasted time and dropped stands. In fact, the Nantahala & Pisgah NFs have the highest rates of project-level attrition of any forest in the ecoregion.

Fortunately, stakeholders have found better ways to work together. In some Districts, stakeholders built a shared, collaborative understanding of how timber harvest could be used to restore degraded systems. Capable agency leaders reflected their consensus at the project level and found new ways to fund important work that wasn’t always viable on its own. Although not uniformly, things got better.

This story, as unique as it felt to us locally, was happening in similar ways in different places across the country. Stakeholders were finding ways to transcend conflict. It was the right time to unveil the new planning rule, which sought to build on the insights earned in local laboratories: ecological restoration is a unifying goal, and consensus is the surest way to identify the highest priority restoration work.

The Nantahala-Pisgah Plan

Local stakeholders were so excited to put the planning rule into practice that they formed a planning collaborative in 2012, well before the agency kicked off its own process with a 2014 Assessment. While the process has not been without hiccups, the Nantahala Pisgah Forest Partnership has generated comments and recommendations with full consensus at each major step of the process including detailed recommendations on the Draft Plan in 2020. Full disclosure: I am proud to be a member of the Partnership, but I am speaking here only for myself.

The Partnership’s agreements cover every major issue from recreation to timber to recreation to wildlife habitat to wilderness. Without taking away from the importance of other issues, my focus here is on the ecological, social, and economic issues orbiting the Forests’ timber harvest program. The “where, how, and why” of logging were subjects of intense debate and compromise in the collaborative setting. The agency likewise spent most of its attention on goals that could be achieved through use of timber harvest.

The Partnership’s agreements were meant to be taken as a whole, and they recognized that management levels could increase considerably while also improving ecological outcomes if the Forest Service would commit to do the right kinds of things in the right places and provide safeguards for disturbance-sensitive ecological values.

The Final Plan, released in late January, purports to hit those targets:

Unlike the previous plan that framed activities in terms of outputs and traditional standards and guidelines, the revised plan developed desired conditions for each ecological community. By using ecological communities, projects will consider needs across a broader landscape, better enabling an increase in pace and scale of restoration.

Reader’s Guide at 5. The plan attributes these ostensible improvements to collaborative input, noting that collaborative stakeholders “created innovative approaches and processes” that “helped to create a more fully implementable plan.” FEIS App’x H at 12.

If only the plan content lived up to those intentions.

Does the Plan prioritize ecological restoration?

First, and crucially, the Plan does provide detailed, well-supported desired conditions for each ecological community, or “ecozone.” Plan at 54–64. These reference conditions are grounded in the best available science and provide unifying direction for future management. Each set of “key ecosystem characteristics” describes characteristic species composition from the canopy to the forest floor, plus characteristic disturbance patterns and structure. They explain, for example, that within moist, productive ecozones, disturbance is dominated by gap-phase dynamics, which produce a pattern of small gaps and fine-scale diversity. Dry forests, on the other hand, should have larger patches and relatively more young and open forest conditions. These key ecosystem characteristics, moreover, are essential to maintain and restore wildlife diversity: some species need small gaps within mature forests, while others need larger patches. Plan at 64; FEIS App’x D at 12. The Forest Service got the reference conditions absolutely right.

After painstakingly describing the key ecosystem characteristics for each ecozone, however, the Plan disclaims any requirement to move toward these desired conditions. The mantra is repeated throughout the planning documents: Projects may “locally deviate from the [natural range of variation]” in order to balance age classes at the forest-wide scale. Record of Decision (ROD) at 66. That’s because the Plan’s default tool is scheduled, even-aged harvest. Plan at 91, TIM-DC-06 (describing scheduled timber program). This type of harvest will occur even in ecozones where large-patch early seral habitat is uncommon under ecological reference conditions. While the Plan sets a modest target for creation of open forest conditions in fire-suppressed, dry forests, it anticipates that the overwhelming bulk of harvest will be even-aged and located in mesic systems. FEIS App’x D at 46-49 (modeling the anticipated timber sale program).

This program of work would not restore characteristic, fine-scale structural diversity in ecozones where it is needed. Indeed, the agency acknowledges that fine-scale disturbance processes aren’t currently happening at natural rates because the forests are in an even-aged condition due to past logging. ROD at 66. A mostly-even-aged harvest program would keep the forest on a treadmill that precludes reaching ecozone desired conditions for structure. The Plan would also allow the continued degradation of species composition caused by even-aged harvest where it is ecologically inappropriate. See FEIS at 3-160 (acknowledging that “less is known about the silvics and reestablishment” of characteristic species in cove ecozones).

The planning team does express an intention to do better work than the Plan’s bare minima. The Plan lists a few “management approaches” to address conditions where there is general support that timber harvest will improve species composition and structural diversity at relevant scales. Plan at 71-72. As recent projects demonstrate, however, intentions aren’t binding at the project level. Neither are management approaches. Targeted, site-specific restoration is an explicit goal only in the “Ecological Interest Area,” which covers 2.1% of the landscape. ROD at 56. Meanwhile, even-aged harvest is scheduled on a whopping 58% of the landscape.

Of the “suitable” management areas, moreover, over 100,000 acres (about 20%) are existing old growth, rare habitats, and wilderness inventory areas that have already been mapped by NGOs, the state, and the Forest Service, respectively. On average, therefore, 20% of harvests proposed under the new Plan are guaranteed to generate conflict—a depressing reminder of the 20% attrition rate that has dogged the old plan. When projects are developed in these areas, there are no standards or guidelines protecting their unique values. Whether to harvest old growth is left entirely to the District Ranger. State-delineated rare habitats can be harvested after “coordination” with no strings attached. Unroaded areas may be roaded without limitation. As in the old plan, conflict is the only backstop to prevent harm to these values.

The Forests argue that even-aged harvest counts as “structural restoration” anywhere it occurs, including areas with high conservation value, because it will restore young forest conditions at the landscape scale. But the Forests did not define restoration at the landscape scale; they correctly recognized that restoration means different things in different ecozones, which is why the Plan sets desired conditions at the ecozone scale. Yes, young forest is an important component of structural diversity, but the characteristic patch size and distribution of young forest is different in each ecological system, and those differences matter to the wildlife associated with each system. Ecological restoration in the Southern Appalachians simply cannot be reduced to “balancing age classes” at the landscape scale.

Why would the Forests set desired conditions for its ecozones but then forecast that it will ignore them in project after project? According to the agency, targeted, site-specific restoration actions to restore key ecosystem characteristics for ecological communities would be too expensive. Without scheduled harvest, “there would not be enough financial resources” to execute a self-sustaining timber sale program. ROD at 56. Timber receipts. Economic efficiency. The philosophy of the 1982 Rule lives on.

To sum up, the Forests argue they cannot restore characteristic species composition and structure at the desired levels with current budgets, so they conclude they must take actions that individually will not contribute to NRV, and when added together will be inconsistent with NRV. That is not how the planning rule works. The planning rule requires each planning unit to maintain and restore NRV, 36 C.F.R. §§ 219.8(a)(1); 219.19, and to ensure that its objectives are within its fiscal capability, id. § 219.1(g).

Failing to identify types and levels of restoration work that can be achieved with expected budgets isn’t just bad planning; it also creates a self-defeating cycle. Without clear price signals, agency higher-ups (much less Congressional appropriators) will not know how much funding is needed to truly restore our forests. By conflating ecological restoration with scheduled timber harvest, a local Forest may preserve some future flexibility to continue with a timber sale program even when budgets are low, but it undermines its own ability to seek and justify the budgets it needs to do the most important work.

This is not to say that there is no room for timber production on the Nantahala-Pisgah, or that the Forests must set trivially small objectives that do not meet economic or social needs. The Partnership offered consensus recommendations that would have allowed the Forest Service to grow its timber program while also meeting its ecological restoration obligations. Did any of that work make it into the Plan?

Does the Plan reflect collaborative input?

The Partnership reached consensus and provided detailed input at every major checkpoint of plan development, covering the full range of issues from land allocation to wilderness recommendation to plan components. Boiled down, our recommendations for vegetation management included:

Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership Recommendations

| Increased levels of timber harvest at current budget levels

| paired with | Protections for steep slopes and streams, old growth, areas with high diversity, and rare habitats

|

| “Tiered objectives” (Stretch goals) to allow the Forests to increase levels of timber harvest even further if additional resources are available | paired with | Adaptive management “triggers” to gauge whether the Forests have the capacity to mitigate negative impacts before moving to stretch goals

|

| Scheduled timber production on a suitable base that excludes areas known to have high potential for conflict

| paired with | Wilderness recommendations that would be supported for designation after meeting benchmarks for success in plan implementation

|

| An unsuitable management area that allows for the use of all appropriate tools, including timber harvest and road construction, to accomplish ecological restoration based on site-specific needs

| paired with | Backcountry management in which restoration would occur primarily by use of natural disturbance and prescribed fire |

| A high degree of flexibility to develop stand-level prescriptions

| paired with | A “pacing” mechanism to ensure that high-consensus restoration occurs alongside scheduled harvest |

In short, the Partnership asked the agency to increase harvest levels and improve ecological outcomes—to “do more, better work.” To succeed with current budgets, we knew that we needed to avoid unnecessary conflict. Each of the recommendations was therefore calibrated to proactively address tensions that would otherwise create project-level friction.

For example, all members supported levels of harvest that are beyond the Forest Service’s current capacity, provided that increasing harvest levels does not exacerbate the road maintenance backlog (a proxy for risk to water quality) and the spread of non-native invasive plants. So, we proposed “tiered objectives,” or stretch goals, which were accompanied by adaptive management triggers (e.g., reduction of the road maintenance backlog, treatments levels for invasive plants). When we can demonstrate that we can keep up with the work needed to mitigate negative impacts at Tier 1, then we know we are within our fiscal capability to stretch to Tier 2.

As another example, some members strongly felt that project-level flexibility was essential to meet restoration needs in viable timber sales, but other members were worried that commercial realities would lead to too much even-aged harvest in the wrong ecozones, like coves. These are inherently plan-level questions: how much is too much? Failing to answer those kinds of questions in the plan will create the conditions for sustained conflict at the project level. To avoid that, we proposed a pacing mechanism. We asked the Forest Service to track types of harvest and ensure that at least half of the total is in one of several priority treatment types—common conditions where timber harvest (including commercial harvest) can maintain or improve stand-level composition or function.

These were innovations we believed would not only solve local problems, but might also be useful for other forests with similar challenges. Indeed, some kind of pacing mechanism is essential to meet the goals of the 2012 rule. Ecological restoration does not have a cookie-cutter solution. It requires some measure of flexibility to do the right things at the project level, but it also requires some mechanism to ensure that we’re doing them in the right proportions in the right places in the longer term.

Unfortunately, the Forests rejected these carefully balanced recommendations. They agreed to increase timber harvest levels, but declined to include any pacing mechanism to ensure that the types and proportions of harvest would restore ecological integrity. They adopted tiered objectives, but they declined to adopt the triggers needed to determine when we are ready to move to the more ambitious targets. They emphasized scheduled timber harvest, but declined to limit it to areas without high potential for conflict. They created an ecological restoration management area but declined to put any substantial acreage in it, instead enlarging the suitable base.

Despite these choices, it’s hard to argue that the planning team has not been committed to public process. At stakeholders’ request, the DEIS alternatives were deliberately calibrated to keep stakeholders from retreating to their corners. During plan revision, planners attended dozens of meetings. Specialists were generous with their time and expertise. And the agency clearly expects the collaborative process to continue into implementation. Plan at 25.

Yet the Forest Service did not roll up its sleeves and actively engage in the process of developing collaborative solutions. Agency thinking happened in a black box, with progress revealed only during formal public comment periods. ID Team meetings were closed, and there was minimal dialogue or feedback. With a Plan that describes work far outside the zone of consent, it appears that consensus proposals were not understood or valued. As a result, it is hard to trust that the agency’s commitment to the collaborative process will result in implementation of collaborative outcomes. Indeed, if project-level discretion and collaboration were enough, we wouldn’t need a new plan.

Here’s how things look in hindsight: Dozens of professionals and volunteers spent eight years working to build consensus at the Forest Service’s request. We were asked to put aside past conflicts created by a parade of zero-sum projects and to imagine a different future. We were asked to be ambassadors to our respective communities. And we showed up. We stretched our comfort zones to the limit, and we handed the agency a roadmap for ecological and social sustainability. Meanwhile, the Forest Service was digging a moat around the plan it intended to finalize from the start—a plan that makes our work irrelevant.

The 2012 Rule after 10 Years

There you have it. Better intentions; fewer commitments.

I realize that some of you will read that as a good thing. Some will argue that increased agency discretion will result in bigger accomplishments. Others will note that a lack of protective standards will cause greater harm. Still others will hope that, despite a lack of clear plan direction to protect conservation values and restore key ecosystem characteristics, we will find a way forward anyhow. That the relationships, improved understanding, and good intentions formed during the past ten years will help us design successful projects in the next fifteen. (“The real plan is the friends we made along the way!”)

For my part, I cannot believe that the 2012 Rule was intended to fund years-long, expensive processes that don’t produce decisions to solve problems. If we’re simply hoping that we can reach the same compromises again later at the project level, why not reflect them in the Plan now? Why did we accumulate ten years’ worth of analysis and consensus-building only to defer the decisions to the project level, where we can analyze and contest them again and again? These questions, moreover, are bigger than any single plan revision: why should self-respecting stakeholders invest years in future collaborative processes if their collective input can be so dismissively rejected? In the interest of protecting both agency and stakeholder time investments in this planning process and encouraging similar investments in future planning processes, the Forest Service should make decisions now that will reflect consensus and improve efficiency during implementation.

If the Nantahala-Pisgah’s Revised Plan is any indication, we have a long way to go to realize the promise of the 2012 Rule. I continue to believe that the Rule’s innovations—ecological restoration and consensus-building—are the agency’s path to continued relevance, but the 2012 Rule will ultimately be judged by the projects (and, unfortunately, by the conflicts) that it produces. Based on our local experience, what is working for the Rule, and what are the challenges?

- Identifying and ensuring progress toward restoration goals:It is possible to develop broadly supported reference conditions for ecological restoration in distinct ecological systems, even in highly altered eastern forests. There is good scientific information available, much of it developed by partners and agency professionals working together.It is harder to craft plan components that can make meaningful progress toward reference conditions with anticipated budgets. The problem is simple: under an ecological restoration paradigm, the highest-priority work is often the least economical. On the other hand, there is a real potential for increasing budgets in coming years. Although the planning rule’s fiscal capability requirement is important, it should not be a straitjacket forcing planners to choose between (a) trying to justify doing the wrong things because they can pay for themselves and (b) doing nothing at all.Surmounting this problem requires a willingness to innovate beyond the planning rule’s text. Tiered objectives and adaptive management triggers offer a platform to justify additional funding, incentivize partner contributions, and get more done. But doing more is not an end in itself. A pacing mechanism is essential to ensure that the easiest or most commercially viable work does not displace higher priority work or get ahead of mitigation needs. Both of these innovations can be incorporated into traditional plan components.

Increasing the pace and scale of ecological restoration also requires more thoughtful and efficient land allocations. The Forest Service must ensure that known conservation assets are not mapped into suitable management areas, where plan-level acreage and volume goals take priority over local values by default. Such allocations inevitably will result in continued project-level conflict and attrition. Conflict as a sideboard for conservation values can only “work” at low levels of harvest; it will not allow us to scale up without damaging ecological values and the public trust.

- Supporting, participating in, and reflecting collaborative work:The Forest Service has learned a great deal about how to create opportunities for collaboration and to provide support to its stakeholders with information and resources. This was an important goal of the planning rule, and the Nantahala and Pisgah NFs have taken it seriously.The agency “black box,” however, remains a major obstacle to effective collaboration. When planners believe they know the right solution already, they are likely to shield the messy parts of the process from scrutiny. Collaboration works best, however, when agency staff are willing to work toward solutions as participants. The agency should communicate better about its own institutional needs and limitations to support consensus-building around new approaches that will work for partners and the agency alike.But it is essential that planners understand they need the public’s help to find the right answer, and they must be willing to reflect consensus in the plan itself—to share decision space. While some forests and districts have taken the plunge, there remain pockets of institutional resistance. Collaborative stakeholders will often ask for guardrails to ensure future actions stay within the zone of consent, and those guardrails can be at odds with agency preferences for greater discretion. Agency leaders must learn that setting limits during the planning process isn’t at odds with agency discretion but is instead an efficient way to exercise agency discretion. Ultimately, collaborative planning must offer stakeholders more than a request to trust its intentions. Trust requires accountability.

The Nantahala-Pisgah Plan is caught in the middle between what the agency is getting right and the lessons it has yet to learn. It’s optimistic but unfinished. Fortunately, there is still time to get it right. This plan is too important to give up on yet—both for the Nantahala-Pisgah and as a model for other forests that are trying to overcome histories of conflict.

This is also a make-or-break moment for the planning rule. Ten years in, there are no more excuses. The rule is not in transition any more. What the rule means here, now, is what it really means. Can the agency commit to work for better outcomes, build trust, and demonstrate its relevance to a public that is increasingly worried about the climate and biodiversity crises? Or will it teach the public that restoration is just another euphemism for business as usual? The next few months will tell.

Sam’s detailed and lengthy treatise sums up to 1) timber management is the #1 forest plan issue; and, 2) forest plans don’t make any meaningful timber management decisions. I agree.

Forest planning is a waste of time, except for planners, for whom it is job security.

Maybe NFMA should be repealed?

Talk about fewer commitments!

Perhaps. But only if it is replaced with a dominant use statute favoring ecological integrity.

Hi Susan: What, exactly, is “ecological integrity?” I’ve been hearing and reading terms such as this for more than three decades now, and no one has been able to clearly explain what this means — or why it should be a “dominant use?” Seriously, I think terms such as this, entirely open to individual interpretation, should be excluded from any planning process, rather than emphasized or even integrated. I’d be very interested in a thoughtful response.

Bob, this is a strawperson argument you present. Ecological integrity has objectively been defined and discussed in the peer-reviewed literature.

Ecological integrity is defined in the 2012 NFMA planning regulations at 36 CFR 219.19 as “The quality or condition of an ecosystem when its dominant ecological characteristics (for example, composition, structure, function, connectivity, and species composition and diversity) occur within the natural range of variation and can withstand and recover from most perturbations imposed by natural environmental dynamics or human influence.”

The concept has been analyzed in the peer-reviewed literature as well. See for example:

– Karr et al., Ecological integrity is both real and valuable (2021) available here: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/csp2.583

– Wurtzebach and Schultz, Measuring Ecological Integrity: History, Practical Applications, and Research Opportunities (2016) available here: https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/66/6/446/2754289?login=true

Ecological integrity should be the dominant use of our national forests because multiple use has been a demonstrable failure. If multiple use worked, we wouldn’t have increased species listings, declining water quality, increased wildfire risk, and declining community resilience, among other issues.

An emphasis on ecological integrity would possibly better deliver multiple benefits/uses than trying to be all things to all people, as multiple use does.

Of note, your first reference Kerr at al is a counterpoint to the negative arguments of Rohwer and Marris “Ecosystem integrity is neither real nor valuable” https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/csp2.583

I found the negative article entirely unconvincing although not without some interesting concerns.

For a lay-person such a myself I thought the two articles sufficed for me to gain a reasonable understanding of the term, its current use, and its faults and features. The features far outweigh any faults as far as I am concerned.

“If multiple use worked, we wouldn’t have increased species listings, declining water quality, increased wildfire risk, and declining community resilience, among other issues. ” Susan, could you explain how you see that these would not have occurred under managing for “ecosystem integrity”?

My point is that multiple use is a failure and we need to try something else. Ecological integrity is worth trying in my view.

I don’t think you can “objectively” define an any abstraction including “ecological integrity” or even “biodiversity” “social justice” “equity” “climate change” “conservatism” “nationalism” and so on.. they’re just terms that people can define, and others can contest the definitions of. Some can, via political power or privilege, put their definition into statutes or regulations. To me, it doesn’t matter whether it’s scientists defining or other folks.

As you just pointed out on the Nantahala-Pisgah, the Forest objectively defined “ecological integrity” by its forest plan desired conditions for key ecosystem components. Other forests are doing the same when they revise their plans, though there can be scientific debate about whether it is the “right” number (just like about anything else).

I mean, okay? But is nihilism pointing you to a better alternative? Because otherwise you’re just assenting to a raw political struggle, which is a worse version of your reasons for not liking ecological integrity, right?

I completely agree with Sharon’s observation: “I don’t think you can “objectively” define an any abstraction including “ecological integrity” or even “biodiversity” “social justice” “equity” “climate change” “conservatism” “nationalism” and so on.. they’re just terms that people can define, and others can contest the definitions of.”

Exactly right. Maybe “peer reviewed literature” has come up with some kind of definition that the average citizen can comprehend, but I seriously doubt it. “Contesting definitions” is good job security for academics and lawyers, but pretty much useless for discussing with most everyone else.

“Planning” — particularly when involving the public — should be conducted in Plain English with quantifiable objectives in order to be functional, in my opinion. Pitting “multiple use” against “ecological integrity” seems more like politics than planning.

Great question, Sam! I’ll write a post about other land management folks and the abstractions they’ve chosen and we can discuss the pros and cons.

To paraphrase George. E.P. Box, “all abstractions are wrong, but some are more useful than others.”

That quote is similar to the one about models. 😃

It is the same quote, I just paraphrased it!

Maybe.

This sure supports my observations that the agency still looks a lot like the volume target-driven Old Forest Service. I would agree with Andy’s #1, but #2 would be that the Forest Service doesn’t WANT to make any meaningful timber management decisions that would tie its hands because #3 is how important money is behind issues #1 and #2. (I think wilderness recommendations are also key issues, but solving the timber problem would help a lot with that.) Of course, when a forest plan establishes suitable acres it creates the problem that it doesn’t want to have – get the cut out from those acres.

I haven’t studied Andy’s proposed KISS, but this seems to be what it would have forest plans do for timber management:

“(b) A land management plan revision shall:

(1) Decide the vegetation management and timber harvest program and the proportion of probable methods of tree removal;” (and the “program” would be pretty detailed)

Maybe that could force the kind of commitment that the Forest Service doesn’t want to make, but I don’t see how that would be “Simple.” It would be interesting to see what would happen if the Forest Service was honest with its public planning participants about how its program budget process works, and its “fear of commitment” (a phrase I used that marked the beginning of the end of my FS career).

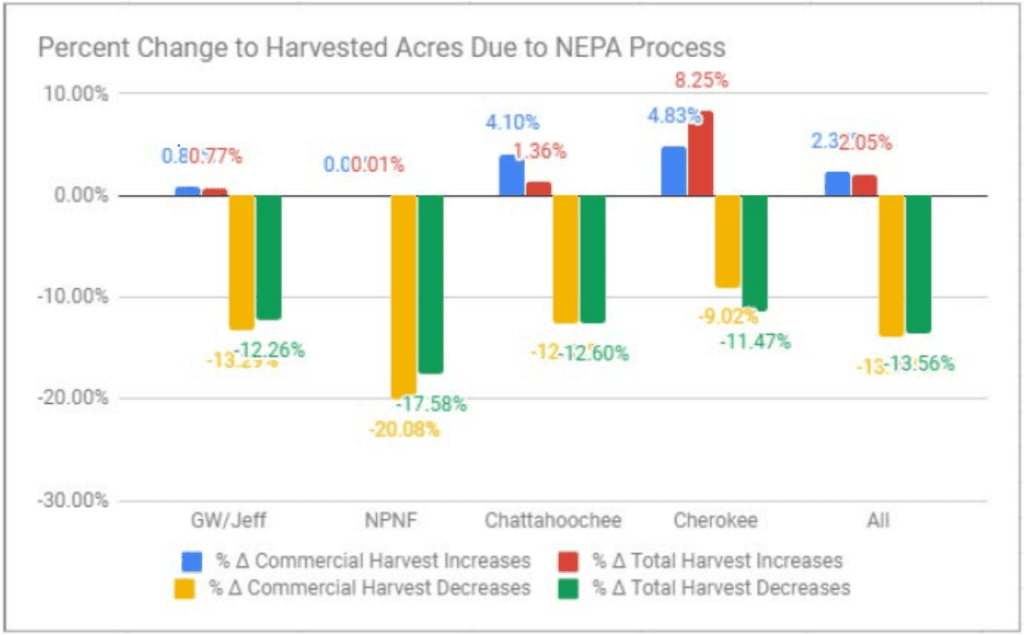

There are some staggering numbers in the details of the plan section 3.4.10 Timber Resources of the FEIS. At the height of the logging free-for-all in the 1980s Total Annual Sold volumes were in the range of 10-12,000 acres and 90-120,000 CCF. Thankfully, those annual levels declined to roughly 780 acres and 18,000 CCF or about 23CCF/acre in the 2000s. (Figure 120 FEIS). Table 208 of the FEIS shows PWSQ targets of 5.0 MMCF and 11.1 MMCF for Tier 1 and Tier 2 respectively. That’s 50,000 CCF and 111,000 CCF respectively for Tier 1 and Tier 2. I’m at a loss to understand the huge increase in Tier 2. Keep reading from there and in Table 210 the plan shows 107,751 acres as viable and operable with current access and 136,770 acres more viable and operable with road building. They project a 127% increase in acres will give a 284% increase in PWSQ. The Tier 1 goal is from 2,200 acres from a base of 107,751 acres and table 211 shows a Tier 1 goal of 51,339 CCF/yr at 23CCF/acre. For Tier 2 the yield increases quite significantly. Tier 2 calls for 4,700 acres per year, a 213% increase, but the yield is 176,114 CCF at 37CCF/acre. There’s no explanation of how they increase the yield per acre by 161% in Tier 2, but I can only guess that is possible because you are logging the oldest and biggest tree. BTW – the 176,114 CCF target significantly contradicts the 111,000 CCF target in table 208.

The plan highlights that the 2,200 and 4,700 acre annual targets are only a tiny fraction (about 2% and 4% per decade) of the whole forest.

Page 3-353

Given these constraints, the consolidated terrestrial ecosystems objectives in the plan that would use timber harvesting (regeneration and thinning), identify roughly 22,000 acres per decade (Tier 1) or up to roughly 47,000 acres per decade (Tier 2). This equates to approximately 2.1 percent (Tier 1) to 4.5 percent (Tier 2) of the total land base over a decade being impacted by timber harvesting.

But that’s an incredibly misleading statement. The suitable acreage for timber production is only 459,175 acres. Tier 1 is then 4.8% per decade or 9.6% over the life of the plan. Tier 2 is then 10.2% per decade or 20.4% over the life of the plan. But even those much larger numbers don’t tell the whole story.

Table 210 shows 107,751 viable, accessible, and operable acres for Tier 1. 2,200 acres per year over the 20 year plan cycle is 44,000 acres which is 40.8%. Tier 2 has 136,770 viable, inaccessible, and operable acres with a goal 2,500 acres per year (for a total of 4,700 acres). That’s 50,000 acres over the plan life – 36.5% of the viable and inaccessible base. 20 years at 4,700 acres per year is 94,000 acres from a base of 244,521 viable acres. That’s 38.4% of the commercially viable acreage. There is no discussion of how many new acres will be available in 2042 and whether that 38.4% rate is sustainable.

Staggering figures indeed which are buried in the plan and never expressed so directly. If you have access to GIS another fun exercise is to look at the Operable Lands layer and imagine 1/3 of that area as being harvested over the life of the plan.

In the beginning of this comment I mentioned the free-for-all 80s and the 100,000+ CCF annual volumes – this plan calls for up to 176,000 CCF annually. Wow….

I think there’s a reason why there’s no forward projection of what the forest is going to look like 20 years from now – it won’t look anything like how the forest looks now and in the worst ways.

For the sake of discussion, it could be interesting to have a series of posts including other stakeholders (and maybe even the forest?) view on this. What views do others have, stakeholder and forest alike, on what was incorporated or dismissed from the collaborative effort? One imagines there might be a variety of views on this. Like Rashomon but for planning. I don’t doubt the poster’s perceptions per se, as they clearly make an effort to nuance things and not just drag the agency for not spitting out a plan that repeats whatever ENGO’s mission statement. So kudos for that. All that said, the black-box analogy is tiresome, and while the public clearly must be included, the desire for “shared decision space” raises FACA questions that I lack the experience to think through all the way.

While Andy is likely correct that timber is the most controversial aspect of the plan, and that there can be reluctance to make timber decisions in plans, it would be interesting to look beyond that. Obviously the poster is focused on timber here, but the plan clearly made other decision, from land allocations to NRV descriptions to other resource management components. That of course can’t be captured in a snide one-liner.

Here’s another point of view: “From a forester’s perspective, we don’t know what is going to happen in the forest in five years, much less 15 to 20 years. Having a diverse toolbox is important when you discover changes to the forest due to the hand of man.”

https://smokymountainnews.com/opinion/item/33125-a-grand-opportunity-for-the-usfs-and-partners

From a lawyer’s perspective (and perhaps a judge’s), NFMA says the Forest Service has to make its best guess at what would happen in 15-20 years and plan accordingly. It might not be easy, and it might cramp their (authoritarian?) style to have to go through a public amendment process to respond to changes, but that’s just the way NFMA set things up.

Especially with regard to wildlife. If the plan creates an escape clause that leaves it tools in the tool box that would compromise viable populations on a project-by-project basis, that plan would violate NFMA.

Jon, thanks for posting my point of view. A foresters perspective is just one of many in this process. I do think it’s reasonable that a judge would see the USFS’s desire for flexibility in management allocation as a best guess at what would happen in the next 15-20 years and their take on planning accordingly. As someone that has been at the table with Sam for close to 10 years, I know there are no simple solutions. We have built some pretty incredible relationships over those years, including the USFS. Here’s hoping they lead to thoughtful objections and more trusting partnerships. Stay tuned.

I follow the timber sales advertised by the Forest Service in Southern Oregon and Northern California. I have to say there is not a lot going on. I never understand why people always act like timber sales are the main concern of the Forest Service. My observation has been it is pretty low on their plans of action. My guess is all those trucks and cars at the Ranger Districts are doing something besides laying out timber sales.

I just looked at USAJobs and I see that most western USFS units don’t have job announcements (for timber) in place, yet. Since the USFS is banking on having lots of timber work, they sure don’t seem like there is any sense of urgency on getting projects started. I do suspect that they will first offer temporary GS-4,5 and 6 positions, hoping to grab as much experience as they can. Their fall-back position would be to hire a bunch of GS-3 people, and hope for the best. Since Region 5 will need maybe 200 new timber techs, they sure are gambling on losing a large chunk of the coming summer work season. They currently have no job announcements, or even outreach for timber work.

There is a mass hire/collective hire nationally for the Forest Service for foresters and forestry technicians this month. I believe the forester positions will be advertised this week and the technician positions shortly thereafter. These are silviculture and timber-related forestry/forestry technician work.

I suspect that many Ranger Districts will be using ‘conscripts’ for timber work. Some GS-3s are teachable. California should need about 500 of them, all Temps. I’m also guessing that Term Appointments will continue to be ‘taboo’. I guess there is always a chance that OPM could change the rules regarding Temps, too.

Region 5 is also going to need hordes of Temporary ‘Ologists’, willing to share ‘barracks’ with other strangers. There’s a lot that can, and will, go wrong, with all those millions of dollars on the line. Remember when timber temps participated wildlife surveys? (I was one of them.)

As a specific note, bracketing larger claims that you conclude with, the first piece you cite is directed at Rohwer’s piece and is also largely oblivious to the more nuanced argument it purports to be responding to. Bob’s point is only a partial strawman, in that you are correct that “integrity” has a history in the literature, Bob is correct, or leaning that way, in pointing out the concept is often used to cloak whatever value the user already holds, on other grounds, in an air of science-y unassailability. I know that’s not what you’re doing here, but it happens.

To the purported response to the Rohwer piece, while I’m sure the author could do a better job than I, a quick note.

One thing the Rohwer piece attacks is the idea that indices of integrity often base integrity, either explicitly or implicitly, as “no people.” The Karr piece cited is unclear on this point, disclaiming a strictly historical reference but stating “Unlike R&M’s complicated discussion of the meaning of integrity, we define biological integrity as one endpoint on a gradient of biological conditions, ranging from relatively free of human disturbance to nothing left alive.”. This gradient brings with it numerous questionable assumptions which, if made operative in a definition of ecological integrity governing national forests, would be pretty obviously problematic for more than just philosophical reasons.

Second, is the move to elide “biological integrity” with “ecological integrity”. While there is likely overlap, it’s not clear that these are the same thing. The cited IBIs for aquatic organisms are considerably more focused than the NFMA reg reference to ecological integrity, or, say, the general use of it in discussions, or the vaguely inspiration but light-on-content Leopold quote. The IBIs in these cases are useful proxies that don’t themselves refer to anything other than an aggregate of other information. Another way of putting it would be to say i’m a nominalist about such things. These terms point to other information but are just names that point, and without saying what they point to in any given usage, then they become rhetorical devices.

So I think if integrity is to have any use in discussion, it needs to be made exhaustingly clear (on a case by case basis) what we’re talking about lest it be a high-handed stand-in that conflates value judgements with specific meanings about biodiversity, human use, etc. Like the cited Karr piece does (maybe?) adequately defend one version of the concept as applied to the CWA, in that the information aggregated in the indices proved useful for conservation, but that can’t automatically be extended to other uses. What would a dominant use statute regarding ecological integrity on the national forests define that as, and is there literature that defines indices of ecological integrity for different forest types?

“So I think if integrity is to have any use in discussion, it needs to be made exhaustingly clear (on a case by case basis) what we’re talking about …” That’s what forest planning is supposed to do for each ecosystem in each national forest.

The definition they are supposed to use is in the Planning Rule: “Ecological integrity. The quality or condition of an ecosystem when its dominant ecological characteristics (for example, composition, structure, function, connectivity, and species composition and diversity) occur within the natural range of variation and can withstand and recover from most perturbations imposed by natural environmental dynamics or human influence.” “NRV” is not defined in the Rule, but (despite the Planning Handbook) is generally conceived as being sustainable considering both past and future conditions.

That’s not as clear as you might think, Jon. For example, the species comp is not going to be within NRV if Chestnut is missing. Roads are not within NRV. Many climate modelers say that the climate has already changed things such that many trees systems can’t recover… perhaps that is not “recovering from “most” perturbations” but who decides what “most” is?? My point is that as defined, you can’t really can’t go backward in time. So where does that leave you?

By going back to a Smokey Wired post by Jon in 2014, I learned that the USFS has transformed HRVs into NRVs — and both based on highly speculative assumptions, occasional outright falsehoods, and dubious planning value as defined. In my opinion.

Here is what I wrote about one example of a pre-NRV HRV being used by BLM to create politicized HCPs from academic WTFs: http://nwmapsco.com/ZybachB/Articles/Magazines/Oregon_Fish_&_Wildlife_Journal/20160300_Forest_Science/Zybach_20160300.pdf

Thanks, Bob, I hadn’t seen that.

Many people still think there are three kinds of lies. Lies, damn lies, and statistics. Actually there are at least four kinds of lies when you include bad computer models.

Nicholas: My thoughts, too. Mark Twain published “lies, damned lies, and statistics” in 1907, but attributed it to someone else, who said it earlier.

Eisenhower warned us about computerized modeling in 1969, but it didn’t seem to become a serious problem until the late 1970s and 1980s, when it became a substitute for reality for considering such things as “critical habitat” and “Global Warming.” Twain would have definitely added computerized modeling to his list of lies had he lived long enough to become witness. At least that’s how I see it.

Every time someone criticizes modeling, I would ask what is the alternative. It’s usually a “model” in someone’s head, defended as “professional judgment.” It’s not either/or, and the assumptions in a computer model should be much more explicit for public review.

Hi Jon: I don’t think anyone is against modeling, anymore than being against GIS or Excel spreadsheets. The problem is how they are used — they are not a substitute for actual scientific methods, but they are often used that way. Further, when their outputs are “peer reviewed” by other modelers they are often published as scientific “findings” and enhanced “predictions.” That is where I think they are abused. When they are used to prepare society for “climate change” or to identify “critical habitat” they have proven to be wrong almost every time. The link I just posted regarding my article on BLM HRVs is a good example of these concerns. Models are tools, not prophets. Or science.

“Professional judgment” might be based on some kind of internal “model,” but it is more importantly based on actual experience, not some computer jockey’s assumptions and biases. As the saying goes: good decisions are based on experience; experience is gained through making bad decisions. Some of the worst decisions I have witnessed in forest management the past 40 years have been based on models. We should learn from that.

To Bob’s point, modeling that’s simply algorithmic is worse than no model; because it allows people to let the model think for them and so they don’t think. Proper modeling is an iterative process that requires experts to assess model accuracy and utility and feed that back to the model developers. It is a well-known fact that models are likely to contain inherent biases of the people who create them – thus the need to outside expert validation. Even then, models should be exercised with care while real-world experience and analysis of their predictions shape their improvement. That’s what a good model looks like…

After dedicating eight years of my professional career to the the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Plan, I am feeling demoralized. The Nantahala-Pisgah is a flagship forest and was handed a blueprint by the broadest coalition possible of how to increase timber harvest, do more fire management, increase recreation access, better maintain roads and trails, protect the forest from non-native species, how to proceed with recommending designations, and more. This solution would have given the Forest Service maximum social license and reduced planning burdens at the project level. It would have brought traditionally opposed stakeholders together to achieve common goals. But in the end, the Forest Service chose basically the same outcome they had been peddling since 2016, wasting a whole lot of time by a whole lot of people. This version pleases internal and external constituents that want maximum discretion for pursuing timber harvest on a footprint that is far outside the consensus and local social license – no matter that volume, acres, and other metrics are unaffected by said footprint. This shows me that the Forest Service, despite generational turnover and positive momentum for more collaborative management, isn’t ready for truly collaborative management and doesn’t understand how to support and build its own constituency. I have been of the opinion that better days are ahead. I’m becoming more cynical. It may be that the Forest Service needs to have its mission changed or clarified before it is able to meet the needs of people in the 21st century.

Josh.. I’m curious how do you determine what “local social license” is? It seems like some stakeholders wanted more flexibility and others did not. Also if “volume, acres, and other metrics are unaffected by said footprint,” then what is the footprint’s importance? Thanks!

my 2 cents as a reader – social license is a consensus of agreement born from a collaborative outcome. To Sam’s original point – contention will exist when and where collaborative agreements are not upheld or valued.

But contention existed prior to the formation of the collaborative agreement, and contention outside of the collaborative group continues to exist. I agree that they should be valued.. but what exactly does that mean in practice?

Sharon, you can’t make everyone happy, and probably shouldn’t try. If, however, the Forest Service can do the greatest good, for the greatest number of people, they should. In this case, when you have groups representing every interest and probably 80% of popular opinion that all agree on a plan to produce the very same desired conditions, goals, and objectives as the proposed Alternative, that seems like a good example of social license to me.

Sharon,

I guess another answer is that if you consider a minority of dissenters as a veto over a well informed collaborative effort with broader representation, effectively giving the Forest Service cover to do whatever they want to do internally, I think we simply have different visions of how public land management should work. I value the greatest good for the greatest number (including the land and all life depending on it) over the long term. The value of the footprint of timber production, or rather, the value of places outside that footprint, is the social, physical, and biological value of the places themselves. The Forest Service chose a larger footprint than was needed and in doing so included even more places that would be harmed by timber harvest than they currently have access to. It would be more valuable to everyone – especially people that want more timber harvest – to have an socially, physically, and ecologically efficient timber production footprint. To put it even more bluntly, subsidized timber harvest of healthy, native forest on Forest Service land is a pretty unpopular concept. If you had a plan where 80% of the populace could support the timber harvest program, rather than 75% being opposed to it, why wouldn’t the agency do that?

Hi Josh: It seems as if you are confusing your own opinions with public consensus. When you say things like “the Forest Service chose a larger footprint than needed” and “included even more places that would be harmed by timber harvest” you are clearly stating your own biases — not facts.

When you state things such as “it would be more valuable to everyone” and that current “subsidized timber harvest” is a “pretty unpopular concept” you are clearly projecting your own perspective on to others.

Finally, your rhetorical question: “If you had a plan where 80% of the populace could support the timber harvest program, rather than 75% being opposed to it, why wouldn’t the agency do that?” That’s a pretty big “IF.” No basis in reality or actual numbers being used, so what is the point? Water is wet?

These types of statements undermine the points you are apparetrnly trying to make. Using “the greatest good for the greatest number” mantra as a cover only makes it worse — these are your own thoughts and opinions, not those of the general population, and you should take ownership, rather than taking cover. In my opinion.

Hi Bob, I absolutely do take ownership for those opinions, and I admit, I don’t have demographic data to back up the numbers I am using. But I’m pretty sure there is good polling data on the popularity of logging on public land. Here is an example specific to the Tongass, but over the years this has remained an unpopular idea with everyone from Taxpayers for Common Sense, to “deep green” groups opposed. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/insight-battleground-voters-oppose-more-logging-of-tongass-national-forest. As someone who believes that timber harvest has a place in the Forest Service mission, but is frequently frustrated by proposals to log biodiversity hotspots, key watersheds, and old growth on Forest Service land, I think the Forest Service should be 1) trying to build more support for the timber/restoration work they do and 2) that the Forest Service should increase their credibility by working in places where they can do the greatest good for the greatest number over the long term. What are your thoughts on the matter?

Hi Josh: My thought is that timber harvesting should be a major function of the Forest Service — for reasons of local economics, wildfire mitigation, wildlife safety, old-growth protection, aesthetics, recreational access, and better reforestation planning and forest maintenance moving forward. So, we are starting from basically different viewpoints, but with apparent middle ground.

Where I have problems (thanks for not using acronyms!), are uses of words and phrases such as “biodiversity hotspot,” “key watershed,” and even “old growth.” What do these even mean? Says who? And so what?

For example: the greatest “threat” to biodiversity in western Oregon is a solid canopy of Douglas fir or Sitka spruce. Every once in a while, a squirrel or some mushrooms; no songbirds, butterflies, or large mammals. Similarly, this creates the greater potential/likelihood of a massive crown fire and the loss of any old-growth in the stand. What to do? Pine can usually be thinned, but Douglas fir loves a clearcut. Maybe a partial cut to help protect Douglas fir old-growth and wannabes? Beginning at age 160 or so?

My personal observation has been that a gross reduction of active management (including road and trail maintenance and timber sales) in our public forests in recent decades has directly — and predictably — resulted in a gross increases in catastrophic wildfires and air pollution and directly related losses of wildlife, old-growth, public access, aesthetics, etc. My thought remains that more active management — with a focus on local human and wildlife populations — of our nation’s forests would be wonderful, however unlikely in the near term.

That last paragraph is a great example of where “walking in the woods” could lead you if the only tool you have is a chainsaw. Correlation is not causation, and if we can’t agree on the causes of a problem, we’re not very likely to solve it. There’s also a pretty good correlation to fire suppression and climate change.

Press release from the Center for Biological Diversity:

https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/report-card-north-carolinas-pisgah-nantahala-forest-plan-flunks-2022-03-10/

Report Card: North Carolina’s Pisgah-Nantahala Forest Plan Flunks

100 Organizations Give Failing Grades to Forest Service Plan for Quadrupling Logging

https://forestplanreportcard.org/

Guess what grade the CBD assigned. Right, an F.

That’s what is known as “job security” in the environmental law industry. If they were being honest, they would have probably given the plan an A. Is there a record on how many lawsuits CBD has filed against the Pisgah-Nanthala, or am I just projecting?

Here is an article that covers a lot of the same territory that Sam did. It definitely gives me the impression that this “plan” is an attempt to go back to the “trust us” era of national forest management that inspired the National Forest Management Act in the first place.

https://carolinapublicpress.org/52045/details-of-western-nc-national-forest-plan-drawing-objection/

In particular, the Forest has apparently gotten some really bad advice if they believe, “Just because acres are calculated as suitable or are included in the matrix or interface management areas, doesn’t mean they’re going to be cut.” By the agency’s own definition of suitable acres, it intends to try (and that will be the source of future conflicts). The main point of NFMA was for forest plans to anticipate where and how much they can expect to log, largely to make sure that harvest levels are sustainable. Here, they seem to have missed this fundamental purpose of the law. (Objectives in the forest plan are irrelevant to meeting this requirement.)

So who gets to wear the “trust us” badge? There has been a lot of effort to discredit the USFS and imply that it is run by people less qualified than environmental NGO’s. The “rules”, rightly so, were written to keep this government agency in check, but not to overrule their authority and expertise. Stakeholders early on were told that our job was not to write the plan, as there is a phonebook like manual that lays all that out. But we were asked to collaborate, share ideas, and participate in the process. To my knowledge, more so than ever before given the almost 10 year process. And comment we did and they did listen to us. Heck, the local activist that gave the new plan an F (see above) also praised the USFS for creating NC’s first National Scenic area. The plan is hardly an F and the loudest voices do not get to provide the final grade.

There is a lot of gamesmanship and lawyering happening throughout this process. That’s fine, it’s how the game is played and until we come up with a better one, the way it will be. At the end of the day, this is National Forest and should be managed like one by qualified forestry professionals. I for one believe in the new 2012 Planning process and the ongoing collaboration that is in place to reduce conflict, increase the pace of restoration and hold all participants accountable. And I believe that whatever the final Final Plan looks like there will be opportunities for partners to work together and help the USFS get the resources they need to properly care for these special 1.1 million acres. But crying foul and demeaning capable, hard working people that equally care about public lands into the ground is not collaboration.

I’ll give an example of how the USFS might have earned the ‘trust us’ badge. When calculating the SYL there is a rubric that must be followed. Now we know that SYL is a pretty useless number overall since it’s at a high level and is a number that nobody intends to, nor could ever, make. But the number of acres judged suitable or ‘may be suitable’ by the USFS is a widely cited metric for how little of the forest they could foreseeably manage for timber production. They say something like ‘in a forest with over 1,000,000 acres the possibly suitable base is 700,000 acres and we only judged 450,000 to be possible for timber harvest activities. Wow, they knocked 250,000 acres off – what great news! But let’s back up, part of the new SYL calculation rule, I would say cynically, is to allow the USFS to push out a big number which includes only lands where it’s not legal to harvest, e.g. Designated Wilderness, etc… or simply impossible to harvest, e.g. steep slopes, rivers and streams. There is a specific ‘carve out’ of ‘lands that may be suitable which are defined as “Timber production would not be compatible with the achievement of desired conditions and objectives established by the plan for those lands;” So the lands they are deciding not to harvest from – based on lots of criteria and feedback – get excluded from the SYL and suitable lands only to then be touted as a credit to the USFS for not including them in the suitable base after all. In the case of this plan the USFS decided that Riparian Buffers are a desired condition and objective of the plan and thus considered them as ‘lands that may be suitable for timber’. It might be picking nits to care whether the buffers are above the SYL line or below it, but with respect to trust it tells me a lot that the USFS thinks they are below it – meaning the USFS considers that it’s up to them whether they should put buffers in the plan and we should be thankful they did. In fact, buffers (at least perennial) are required by the planning rule, see 219.8.

(ii) Plans must establish width(s) for

riparian management zones around all

lakes, perennial and intermittent

streams, and open water wetlands,

within which the plan components required

by paragraph (a)(3)(i) of this section

will apply, giving special attention

to land and vegetation for approximately

100 feet from the edges of all

perennial streams and lakes.

(A) Riparian management zone

width(s) may vary based on ecological

or geomorphic factors or type of water

body; and will apply unless replaced by

a site-specific delineation of the riparian

area.

Buffers don’t change per different Alternative, so why are they below the line? What does that say about the USFS attitude towards riparian buffers? Trust dies a death of a thousand cuts…

It’s the sum of little bits like this, scattered throughout the plan that hint at how concerned the USFS is about things like water quality, as an example in this case. I’m not impugning their expertise, I’m questioning their judgement. I don’t know if there was any argument about this decision internally at USFS, but I do know what they decided in the end.

Jon, that raises a question, how is sustained yield considered in the 2012 Rule and regulations?

It’s described in the EIS.

Timber calculations

Sustained yield

Both the 1982 and the 2012 Planning Rules required identification of harvest levels that met a sustained yield. Sustained yield as defined under the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) is that “which can be removed from [a] forest annually in perpetuity on a sustained-yield basis” (NFMA at section 11, 16 USC 1611; 36 CFR 219.11(d)(6)).

The two planning rules interpret this sustained yield differently. The 1982 Planning Rule included Long-term Sustained Yield (LTSY) defined as “[t]he highest uniform wood yield from lands being managed for timber production that may be sustained under a specified management intensity consistent with multiple-use objectives” (1982 Planning Rule, Sec 219.3). The 2012 Planning Rule included a definition of Sustained Yield Limit (SYL) as “[t]he volume that could be produced in perpetuity on lands that may be suitable for timber production. Calculation of the limit includes volume from lands that may be deemed not suitable for timber production after further analysis during the planning process. The calculation of the SYL is not limited by land management plan desired condition, other plan components, or the planning unit’s fiscal capability and organizational capacity. The SYL is not a target but is a limitation on harvest, except when the plan allows for a departure” (1909.12-2015-1, Chapter 60. Pages 7 & 8).

Key differences between the LTSY and SYL center on lands included in the calculation. The 1982 LTSY is calculated from those lands only suited to timber production. The 2012 SYL is calculated off the lands that “may be suited for timber production,” including lands that are ultimately found to not be suitable for timber production. A second, albeit related, difference is the 1982 Planning Rule’s LTSY connection to multiple use objectives and economic efficiency. In comparison, the 2012 SYL is not constrained by fiscal, organization capacity, or multiple use objectives.

What are the key differences?

The calculation of the SYL is not limited by land management plan desired condition, other plan components, or the planning unit’s fiscal capability and organizational capacity.

That part means that the old SYL was an ‘after the decision’ calculation and in 2012 it’s a before the decision. There are very specific steps/rules about the calculation to be found in the rule and in the related docs.

The EIS seems to explain what they did, but that doesn’t really address some important concerns about this approach. I’ve addressed those here: https://forestpolicypub.com/2022/03/18/timber-sustained-yield-requirements-for-forest-plans/

Short version of long story. The Rule passed the buck to the Planning Handbook, which changed the definition from what the agency had used for decades (which NFMA endorsed) without any public notice. I’ll try to post on this next week.

Well, let us all know when the “process” instead of “reality” leads to a similar outcome as Region 5, where Public Lands fail to perform or deliver in any way that the ‘Public’ of any kind wants or deserves. They say California leads the way in the US, and the way California goes so goes the US. Seems true, but I’d ask if anyone gave up desktop GIS exercises and planning and lawyering up and simply took a walk in the woods and chatted with others?

Professional Planners and Lawyers excel at delivering themselves a pat on the back (and paycheck) it seems, while the scientists and public lose (see NFMA 2012 and all that has come from it since).

LOL – walk in the woods? Now you’re crazy talking. Even crazier, so few people go alone into the woods and just let the woods talk to them.

I am always overwhelmed by all the discussion about forest planning. Especially when in come to timber harvesting and especially in the last 30 years. I am only partially familiar with the timber harvesting that takes place on public lands here in Southwestern Oregon and a small part of Northern California. My observations generally are that getting timber sales through the process is lengthy and difficult and always error on the side of caution by our federal land managers. Most of the sales are influenced, some outright negoiated, and in the end litigated if not meeting of standards the environmental community.

But what I really started off to say is being out on our public lands and observing for yourself will give you a better idea what is really going on our pubic lands than all the planning discussions put together.

Bob: I think it takes a lot more than just observation — having actual experience is critical, too. Many times I have been on tours or show-me trips with so-called experts and forest scientists who couldn’t interpret what they were looking at or understand the dynamics that made it possible. The most common error (the “Franklin”) is when they assume the forest is static for some reason — therefore, a clearcut has “destroyed” a stand of trees, and “old-growth” have always occupied a site or area in which they currently exist. My thought remains that we need more experienced forest managers and historians and fewer modelers and lawyers if we are ever going to put our public forests and wildlife into a healthy condition again.

Some might say that this is equally true for decarbonization… we need more engineers and energy producers involved and fewer modelers lawyers (and I’d add ideologues).

“LOL”? That is a nice response to GIS desktop exercises with moderate to no basis in reality, and the insane preference for process and planning over outcome.

Enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Just a little follow-up on how disliked this plan seems to be (even assuming many of the objections are form letters).

https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/14000-objections-filed-against-pisgah-nantahala-forest-plan-2022-03-23/

But.. if one group files an objection everyone else has to file an objection otherwise they don’t get to participate in the objection resolution meetings.

So what appears to be objections from everyone (interests not numbers) might be everyone getting their place at the table.

The USFS has 10 days to post the comments. By my calendar that’s April 1. Hmmm….