There might be a few folks who signed onto this list because they wanted to follow the “new century of forest planning.” Forest plan revisions are finally/still happening. The Custer Gallatin became I believe the 7th forest plan to reach the draft stage under the 2012 Planning Rule. (It’s got some wilderness issues!) The Forest Service revision schedule hasn’t been updated since last June, but here it is. The Chugach National Forest was the 6th draft. There are a number of draft plans that were expected to be out about now, but I haven’t seen anything. Two revised plans are complete. There’s been a noticeable slowdown in forest planning recently: there was only 1 new start in 2018, and 2 in 2017.

Jon Haber

Northern Region Regional Forester talks about bikes in recommended wilderness

I’ve excerpted the portion of the Regional Forester’s objection decision on the revised forest plan that addresses this issue, dated August 15, 2018 (p. 46). It upholds the Flathead Forest Supervisor’s decision to designate recommended wilderness as not suitable for mountain bikes. I’ve highlighted the language in the regulation that addresses the question about whether the only concern should be physical impacts. The objection decision also indicates that the decision to recommend wilderness or not took into account existing mountain biking. It also addresses the alleged bias towards this solution in the Northern Region. This probably pretty much summarizes the current state of the debate from the Forest Service perspective.

Some objectors requested that bicycle use (mechanized transport) be allowed in recommended wilderness, along with chainsaws (motorized equipment) for the development and maintenance of trails, as long as these uses do not preclude wilderness designation.

The areas recommended as additions to the National Wilderness Preservation System are allocated to management area 1b. This management area has plan direction in the form of desired conditions, standards, guidelines, and suitability to “provide for…management of areas recommended for wilderness designation to protect and maintain the ecological and social characteristics that provide the basis for their suitability for wilderness designation” as required at 36 CFR 219.10(b)(iv).

The suitability component MA1b-SUIT-06 indicates, “Mechanized transport and motorized use are not suitable in recommended wilderness areas” as a constraint on these uses to help achieve desired condition MA1b-DC-1 that states, “Recommended wilderness areas preserve opportunities for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. The Forest maintains and protects the ecological and social characteristics that provide the basis for wilderness recommendation” (revised plan, p. 9).

As one of the key issues identified from the public scoping comments, the draft EIS analyzed a range of alternatives for managing mechanized transport and motorized use in recommended areas. Alternative C included the suitability component MA1b-SUIT-06 and alternative B did not. The intent of varying the direction was to assess how this plan component would help the Forest achieve the desired conditions for recommended wilderness. After considering the analysis and the public comment on the draft EIS, Forest Supervisor Weber found the MA1b-SUIT-06 component analyzed in alternative C was the appropriate first step in ensuring the protection and maintenance of the areas he decided to recommend in the draft decision (draft ROD p. 19).Therefore, he modified alternative B to include MA1b-SUIT-06.

The intent of suitability component MA1b-SUIT-06 is to not establish or authorize continued uses that would affect the wilderness characteristics of these areas over time (draft ROD pp. 18-19). By deliberate design, the areas being recommended for wilderness in alternative B modified do not currently have significant mechanized transport use occurring. Per public comment on the draft EIS, boundary adjustments were made in the final EIS to remove areas from recommended wilderness that currently allow mechanized transport and over-snow motorized vehicle use (FEIS, pp. 27-28). As there is some over-snow motor vehicle use allowed in one recommended wilderness area (Slippery Bill-Puzzle) (FEIS, section 3.15.3; appendix 8, p. 8-261), Forest Supervisor Weber has endeavored to accommodate this desired recreation opportunity by changing the desired recreation opportunity spectrum in another area of the forest for potential site-specific designation of additional snowmobile areas 2. With these changes between draft and final EIS, the decision maker found that the eight areas recommended represent high-quality areas on the Forest capable of maintaining their unique social and ecological characteristics, while considering the tradeoffs regarding public desires for other uses of the land.

At the resolution meeting, some expressed a concern regarding an “unwritten rule” in the Northern Region that precluded Forest Supervisor Weber from exercising his discretion to choose the appropriate management of recommended wilderness on the Forest. Although previous Northern Region staff drafted guidance for management of recommended wilderness during land management planning, this was prior to the 2012 planning rule and associated implementing directives. I would like to assure objectors and interested parties that I allowed and encouraged Forest Supervisor Weber the discretion to determine management direction for the Forest per the forest-specific conditions, public engagement, law, regulation, policy, and the direction in FSH 1909.12, chapter 70. As a result, per the discretion described in the Agency’s direction at FSH 1909.12 chapter 74.1, option 2, Forest Supervisor Weber did analyze allowing existing uses to continue (DEIS, p. 26). However, as indicated in the draft ROD, he found the best strategy to protect the wilderness characteristics was to eliminate existing uses per chapter 74.1, option 4.

January litigation

On to 2019 …

Ochoco National Forest OHV trail system

The Oregon district court ruled the U.S. Forest Service failed to satisfy its legal obligation to study wildlife impacts. This case was discussed here.

Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest motorcycle event

Several organizations are challenging decisions that allegedly limit the routes for a motorcycle trail riding event on public land. They challenge the Greater Sage-grouse Bi-State Distinct Population Segment Forest Plan Amendment and special recreation permits issued to them.

Oregon state forest logging practices

In 2018, five environmental and fisheries groups filed a legal complaint against the Oregon Department of Forestry alleging that logging and associated activities in the Tillamook and Clatsop state forests are harming federally threatened coho salmon by discharging sediment into streams. The federal district court will allow the case to proceed as long as the allegations are made more specific.

Bitterroot National Forest public access

A lawsuit by landowners subject to a Forest Service easement claims the agency has encouraged public use, which has become “excessive and disruptive” to the landowners.

Rio Grande National Forest bighorn sheep

The new lawsuit challenges a decision to allow domestic sheep to graze because the risk is high that the domestic sheep and bighorns will cross paths, which could expose the bighorns to life-threatening diseases.

Superior National Forest land exchange

A federal judge is allowing to proceed lawsuits challenging a land exchange between the U.S. Forest Service and PolyMet Mining after a bill that would curb such legal challenges to the swap failed in Congress’ last session.

December litigation

Since it looks like the Forest Service “Litigation Weekly” may have been a victim of the government shutdown, here’s what you may have missed.

Coconino National Forest ski area

The Arizona Supreme Court has squashed what could be the last legal maneuver by the Hopi Tribe to block the use of treated effluent to make snow on the San Francisco Peaks. (The Forest Service was not a party.)

Boise National Forest salvage logging projects

The Ninth Circuit upheld the North and South Pioneer salvage logging projects against NEPA and ESA claims. This lawsuit was previously addressed here.

Helena – Lewis and Clark National Forest thinning project

The District Court upheld a thinning and burning project in the Elkhorn Mountains Wildlife Management Area.

Flathead National Forest timber project

The District Court dissolved the injunction against the Glacier Loon project after the Forest supplemented its NEPA analysis.

Francis Marion National Forest annexation

The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that two Awendaw residents and the Coastal Conservation League may challenge a 2009 town annexation that cut through the Francis Marion Forest to reach a 360-acre privately owned tract. What made the Nebo annexation so controversial was the town’s approach to establishing “contiguity.” In South Carolina, municipalities may annex properties only if they’re contiguous, or touching, their current limits. Awendaw annexed Nebo after also annexing a 10-foot-wide strip through the Francis Marion forest, but the U.S. Forest Service did not sign a petition allowing it. (The Forest Service was not a party and has been strangely silent.)

Kisatchie National Forest hunting ban

A federal judge has upheld a 2013 dog deer hunting ban challenged by local hunters.

Mountain bikes in existing wilderness (redux)

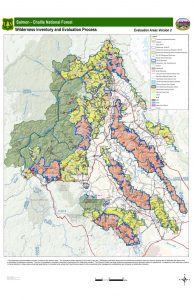

I try to not get too involved in the wilderness debates (there seem to be enough people there already). But I follow planning, and this started out to be a post on the status of wilderness recommendations on the Salmon-Challis National Forest, as part of their forest plan revision process, but there was also this:

“Two places in particular really stand out,” he said. “One is the north side of the Pioneer Mountains. The southern half is in the Sawtooth National Forest and is already recommended for wilderness, and the area around Borah Peak in the Lost River Range. Those two areas we find to have exceptional wilderness character, a lot of scenic values, great wildlife habitat, opportunities for solitude and other things that fit the definition of wilderness character. These areas have been managed as wilderness areas since 1979.”

I wanted to find out what happened in 1979, because this suggests a policy of excluding mountain bikes to protect potential wilderness areas outside of Region 1 (the Salmon-Challis is in Region 4). Instead I found a recent law review article discussing the bigger issue including a couple of questions that have been key in recent posts. It includes the history of the Forest Service policy:

In 1966, the Forest Service wrote formal regulations to implement the Wilderness Act, and defined “mechanical transport” to mean a cart, sled, or other wheeled vehicle that is “powered by a non-living power source.

The Forest Service later reversed course by issuing a declaration banning bicycles in 1977…

The Forest Service flipped one last time in 1984, after various groups, including the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society, successfully convinced the agency to remove the reference to bicycles in the discretionary 1981 regulation.

There is also a good discussion of the legislative intent behind the term “mechanized transport.” The author buys into the interpretation of a previous author liked by the Sustainable Trails Coalition, “Legislative history informs the mechanical transport issue and reveals that Congress “meant to prohibit mechanical transport, even if not motorized, that (1) required the installation of infrastructure like roads, rail tracks, or docks, or (2) was large enough to have a significant physical or visual impact on the Wilderness landscape.” But she adds, “Even if the term “mechanical transport” in the Wilderness Act does not include bicycles as a matter of law, the management agencies have the discretion to ban them, as they explicitly have.” (This includes BLM and the Park Service.) She favors local discretion.

Wilderness decisions are acutely emotional and political, and what it feels like we’re witnessing is how emotions and politics shift over time, sometimes in response to technology. I personally would rather not see mountain bikes in wilderness because it makes wilderness smaller by making more remote areas more full of people, which is not a wilderness value. But maybe people like me are dying out. But I’m not convinced that bikes (large numbers over time) don’t have “a significant physical or visible impact” either, on at least most trails.

So I don’t know why the Salmon-Challis potential wilderness areas may have excluded bikes since 1979. But here is the status of planning for wilderness:

“There are groups out there like The Wilderness Society looking at us as the last best place to designate more wilderness area,” Mark said. “I’ve already got two-thirds of the forest as wilderness. I’ve got local folks, range permittees, outfitter guides and others asking ‘Well Chuck, how much more wilderness do you need?’ That’s a good question and I don’t necessarily have an answer.”

I don’t like the implication that he thinks 2/3 is necessarily a lot (especially if there are going to be more people using wilderness areas someday because they can ride their bikes there).

The Wayne Gretzky approach to fuel reduction

The hockey star is known for saying you have to “skate to where the puck will be.” That seems to be what the Forest Service is trying to do by putting thinning treatments where fire risk is high, but research again suggests that the hockey analogy doesn’t work in forests. Maybe it’s because the “field of play” is so much larger and the entity delivering the puck isn’t on your team (and doesn’t play by any rules). This article plays off of the recent executive order to treat 8.45 million acres of land and cut 4.4 million board feet of timber, “which is about 80 percent more than was cut on U.S. Forest Service lands in 2017.”

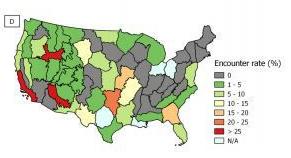

“The Hazardous Fuels Reduction Program received a lot of financial investment and resources over the past 15 years,” Barnett told the Missoulian. “We treat quite a lot of landscapes each year. And less than 10 percent of that had even (been) burned by a subsequent fire. So that raises more broad general questions over the efficacy of fuel treatments to change regional fire patterns.”

“Even if federal land management agencies were able to increase their treatments and meet the President’s goal of treating 8.45 million acres, it would still equate to less than 2 percent of all federal lands,” Pohl said. “It is unlikely these locations will be among the hundreds of millions of acres that burn during the effective lifespan of a fuel reduction treatment, typically 10-20 years.”

And if the goal is protecting homes rather than changing regional fire patterns,

“Research shows that home loss is primarily determined by two factors: the vegetation in the immediate area around the home, and the way the home is designed and constructed,”

You could read this to say that if they treated 2% a year for 10-20 years, there would be a higher encounter rate than historically that might be a better justification, but it doesn’t sound like that is the way they are interpreting it. The map does suggest that southern California and a couple of other places might be looked at differently, and considered a priority for funding.

The author went off script a bit to say that logging is a good strategy to “improve forest health,” but maybe that’s the semantic problem of “logging” vs “thinning.” I’m also wondering if an order to produce board feet doesn’t tend to favor logging (of bigger trees) over thinning?

Michigan national forest considering banning alcohol on wild and scenic rivers

This is probably just another run-of-the-mill people management issue that taxes the limited recreation management resources of the Forest Service; here’s what happens when natural places get so popular they attract people who are not there to enjoy the nature part. The ban would be about “safety and environmental issues on our National Wild and Scenic Rivers,” and maybe there are some wild and scenic rivers act requirements at the bottom of this (the forest supervisor spent some time at OGC). (But it’s mostly interesting to me because I’ve been on these rivers, long ago).

Forest Plan Participation 101

Some tips from a participant in the Manti-LaSal forest plan revision process, which includes developing a “conservation alternative” that “will emphasize the long term health of the forest.”

I’m afraid I’m pretty cynical about the payoff from this approach, but I’d be interested in stories from anyone who feels they had some success. Part of the problem comes from the fact that the Forest Service creates its own structure for the alternatives it develops (such as the choice of management areas, what the different kinds of plan components should look like, how the plan document will be organized), and an outside alternative that doesn’t line up with this would be difficult for the planning team to document and evaluate. Then of course there is the, “I am the professional” bias that resists outside ideas, the “don’t take away my power” bias that resists any actual obligations (standards) in the plan, and the “no-change” inertia bias that defines “reasonable alternatives” as those that aren’t much different from the current plan. At best, it seems like there might be a few surprises that the Forest Service actually likes and tries to use. Tell me I’m wrong.

It looks like Mary is already encountering some bias:

For instance, the Moab Sun News’ article on the public meeting reported that forest service grazing manager Tina Marian said people won’t see a lot of grazing changes in the new plan that aren’t already being implemented on the ground. She shouldn’t predetermine that outcome. The conservation alternative will recommend changes to how grazing is implemented in the forest (which is a part of Moab’s watershed), like reducing the rate of cattle grazing.

It’s not possible to tell where exactly the Manti-LaSal is in the revision process from their website, but there was a comment period on the “Draft Assessment Report” in June of 2017. I think the best time to influence alternatives is probably when the Forest must “Review relevant information from the assessment and monitoring to identify a preliminary need to change the existing plan and to inform the development of plan components and other plan content” (36 CFR §219.7(c)(2)(i)). Any reasonable alternative would have to be traced back to that information, and if there are disagreements at that point it’s not likely that later suggestions would be well received.

In the example above, what did the assessment say about the effects of cattle grazing? The Forest seems to take the position that “historic” grazing was a problem, but “… (C)urrent grazing practices are not having as large an effect on stream stability, as evidenced by the many greenline transects rated as stable in 2016.” But then there’s this proof of bias in the Assessment (I’m not familiar with these “directives,” and unfortunately, “Shamo” isn’t in the “Literature Cited”):

Livestock grazing has occurred on the Forest for over 150 years and will continue as part of the Forest’s directives to provide a sustained yield and support local communities (Shamo 2014, USFS 2014).

They’ve got some other interesting issues on the Manti-LaSal:

The alternative will ensure that pinyon and juniper communities are not removed on thousands of acres for the purposes of growing grass for cattle and artificial populations of elk.

It will require the forest to remove the non-native mountain goats that are tearing up the rare alpine area above 11,000 feet in the Manti-La Sal Mountains. It will not allow honeybee apiaries, which would devastate native bees.

And that’s where part of the Bears Ears National Monument is/was. There was a lawsuit on the goats, and there are several on Bears Ears.

The myth of “coordination”

In recent years this the idea of “coordination” has been sold to local governments as a legal tool to make federal land managers do what the locals want with national forest plans. It’s a myth that periodically needs busting. This article describing the response of the Malheur National Forest and a document from the Northern Region provides a pretty good summary of the history and reality.

“Based on recent local government resolutions or ordinances and letters to some national forests, it appears that some local government officials believe the (National Forest Management Act) coordination requirement means the Forest Service must incorporate specific provisions of county ordinances into forest plans or that the Forest Service must obtain local government approval before making planning decisions,” Hagengruber said.

“This position overstates the NFMA obligation of the Forest Service,” he continued. “The statute does not specify what actions are required to coordinate Forest Service planning with local government planning, and it does not in any way subordinate federal authority to counties.”

“Rather,” he continued, “the Forest Service must consider the objectives of state and local governments and Indian tribes as expressed in their plans and policies, assess the interrelated impacts of these plans and policies, and determine how the forest plan should deal with the impacts identified.”

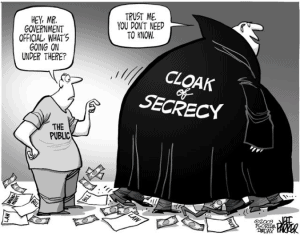

Interior Dept. to limit freedom of information

To add to the lawsuits that result when the government misses its deadline to provide information subject to the Freedom of Information Act, we may soon see a lawsuit against USDI’s effort to not have to provide the information in the first place. Comments on their proposed new FOIA regulations were due Monday.

(The purpose is to) “streamline the FOIA submission process in order to help the Department inform requesters and/or focus on meeting its statutory obligations.”

The department proposes limiting the number of requests that individuals or groups could file each month, and to “not honor a request that requires an unreasonably burdensome search or requires the bureau to locate, review, redact, or arrange for inspection of a vast quantity of material.”

A department spokeswoman said making the process more efficient would “ensure more equitable and regular access to federal records for all requesters, not just litigious special interest groups.”

FOIA represents a strong statement from Congress about the importance of open government. Responses to FOIA requests often reveal illegal activity and become the basis for lawsuits. Still, every administration seems to stamp its own bias on its FOIA procedures, and this is Trump and Zinke.

As a practical matter, it can take a lot of agency resources to comply with FOIA requirements. But as a legal matter, the law is pretty clear about what has to be provided and how fast. Regulations can’t change that. There is nothing in the law that excuses agencies from honoring a request if they happen to take actions that generate “vast” quantities of material, or if some aspect of providing required material is “burdensome.”

(Could the USDA Forest Service be brewing something similar?)