Although my old “fire prevention guard” job title has been superseded by such titles as “fire prevention technician” or “fire prevention specialist” in ensuing decades, I think my approach to the job as I did it on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s—my philosophy regarding how to do the job—remains valid.

I don’t know that any fire prevention guard ever prevented a fire just by riding around in his or her agency vehicle. I know I didn’t because I didn’t. The key to fire prevention patrol success is public contact, and the key to public contact is to get out of the patrol rig and talk with people.

So, instead of just driving through campgrounds and raising dust, I routinely parked my vehicle and walked the campgrounds. That made me available to visitors, either to initiate conversations or to respond to questions. Outside developed campgrounds, I parked a respectful distance from and walked into camps to greet campers, answer questions, and work a fire prevention message and a campfire permit check into the conversation. I did the same along heavily-fished streams or wherever else I encountered forest visitors.

Another way I made myself available to the public was by patronizing resort restaurants along my patrol routes. This cost me more than packing a lunch, but it was a rare noon hour at the Crags Resort or Mono Village restaurants in the Twin Lakes area or at the Virginia Lakes Resort restaurant that I didn’t make at least a few good contacts. I even lunched in sheep camps with hospitable Basque sheepherders a few times.

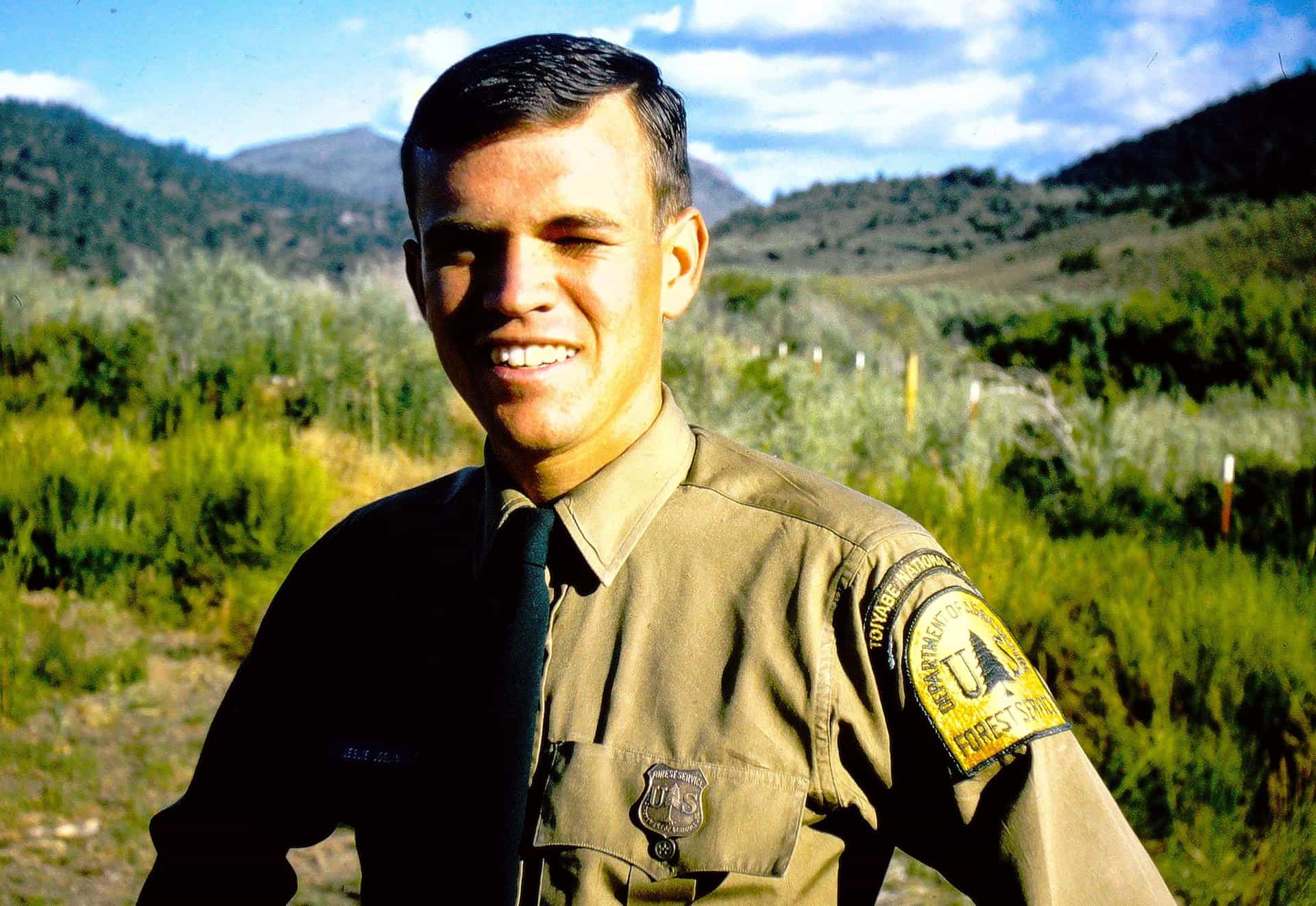

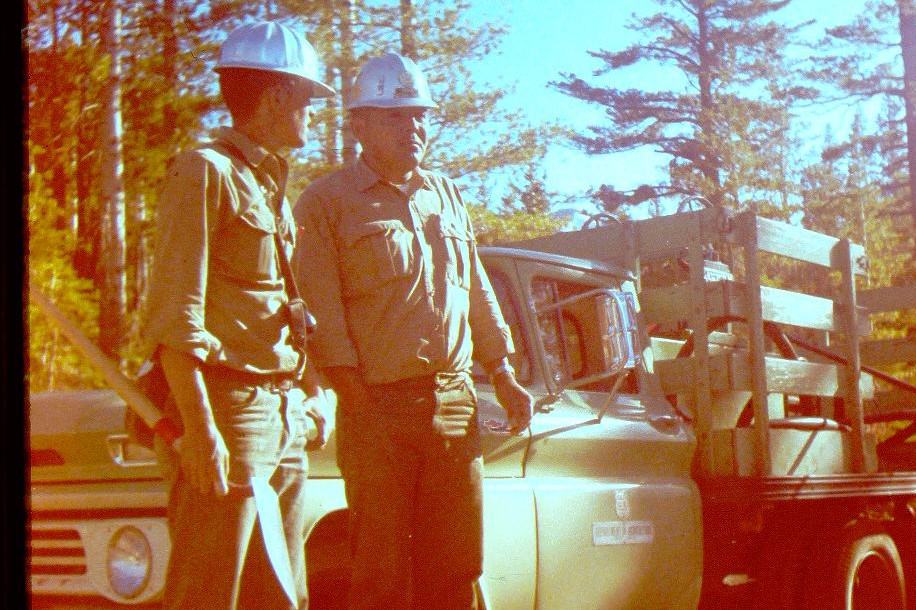

Availability’s partner in the public contact business is visibility, and I made it a point to look the part, to be easily recognized as a Forest Service representative. A good haircut and a clean shave, a freshly-pressed uniform shirt with badge and nametag in place, clean green jeans and solid work boots, all coupled with a pleasant disposition, project a positive image. There is no place in public service, I agreed with the district ranger and the fire control officer, for slovenly appearance and bad manners. I’ve no proof, of course, but I’m convinced this friendly, helpful, face-to-face approach contributed to my success at the job.

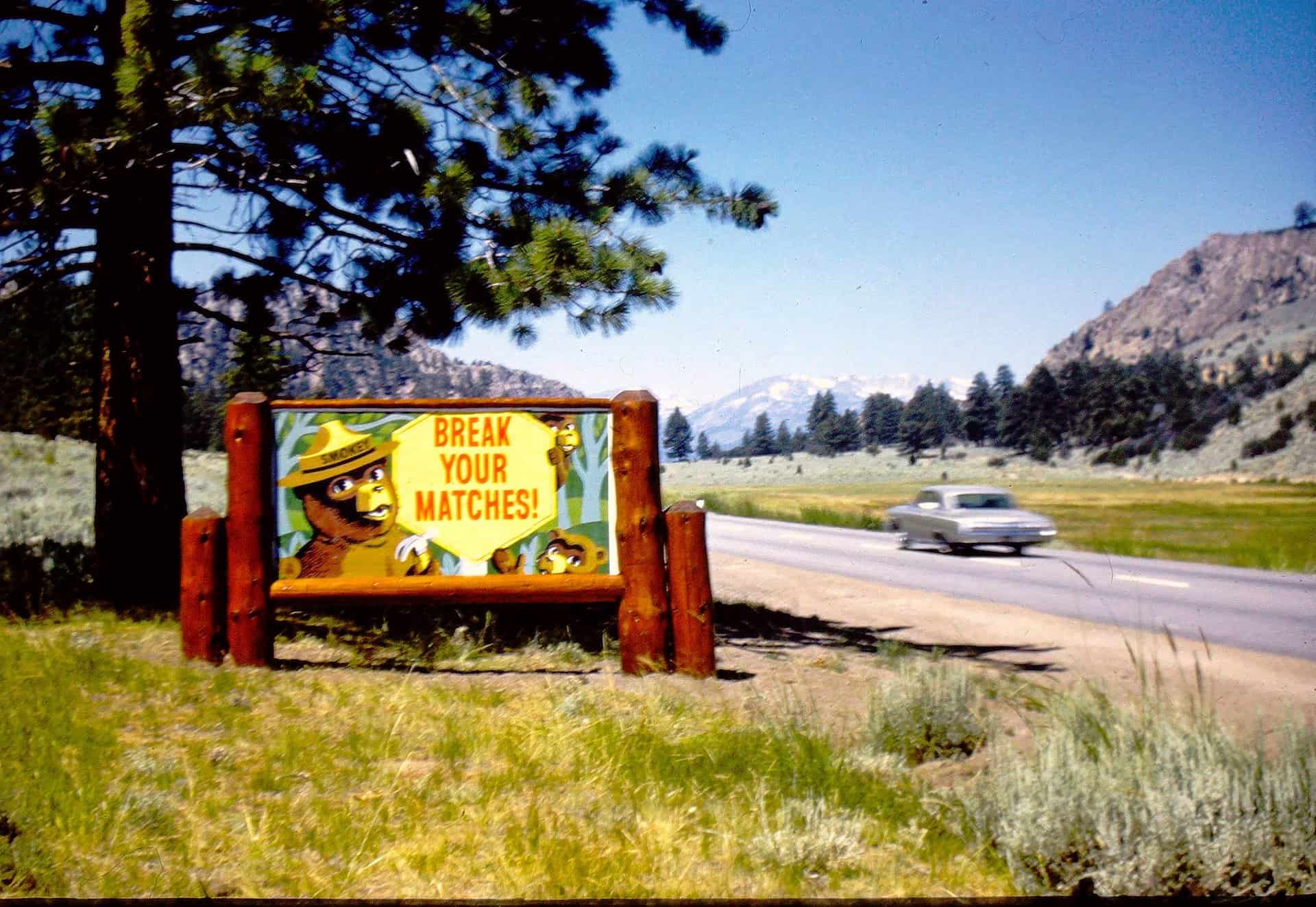

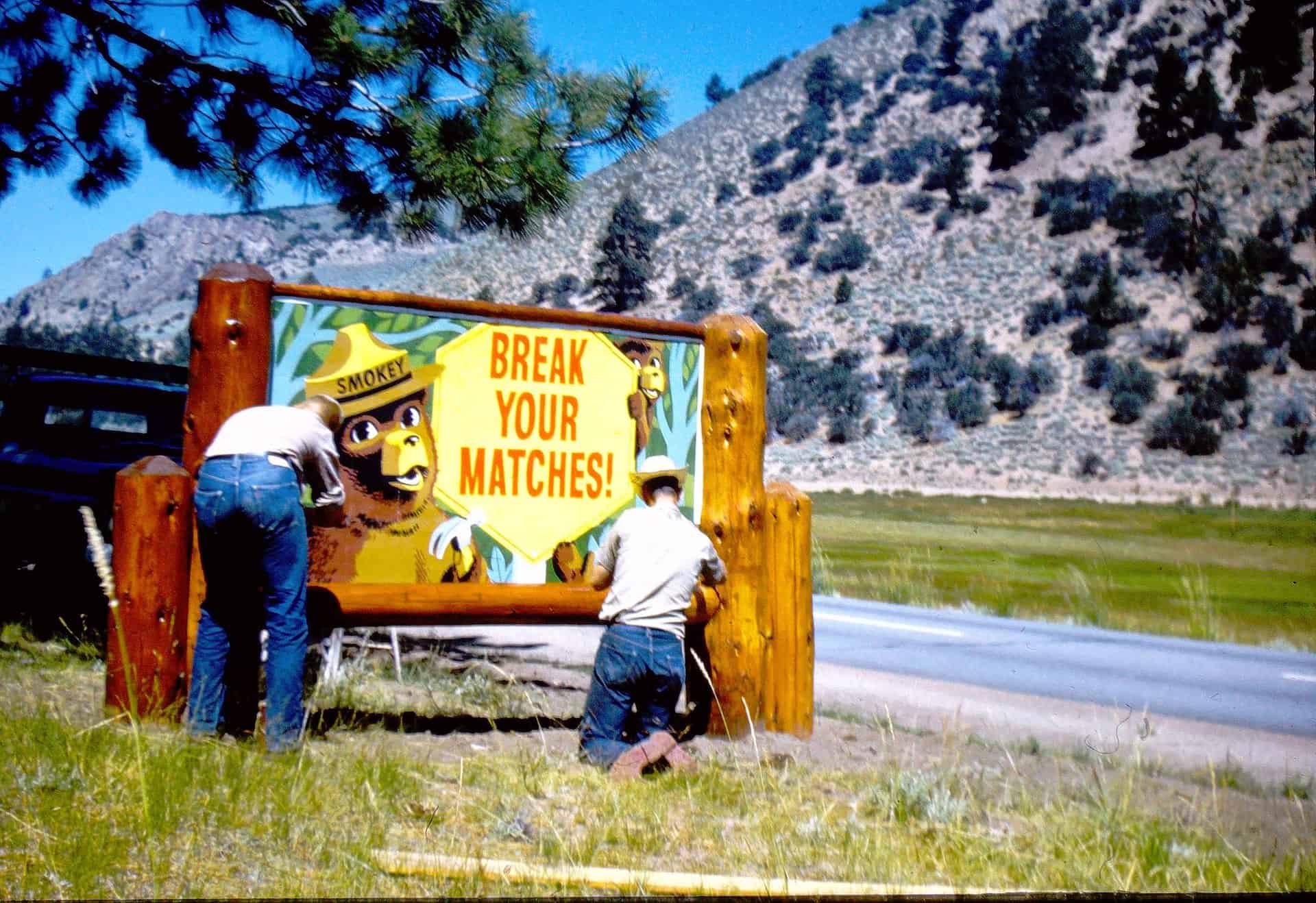

Availability and visibility were enhanced by other patrol route chores. Chief among these was sign installation and maintenance. I often left the ranger station on patrols with new road signs or fire prevention signs to be installed lashed to the rig. In addition to the tank-pump unit and fire tools, there were digging tools, paint brushes, and a five-gallon can of brown stain to help keep all district signs looking fresh. Since signs were almost always along roads or at trailheads, I was available and visible and made valuable public contacts while installing and maintaining them. This approach, I’m convinced, made a positive impression.

And, early on, I learned that—while my primary job was fire prevention—I was expected to know just about anything anyone might want to know about the Toiyabe National Forest and the surrounding country. I made it my job to be a fast learner! And what I knew I supplemented by reference to national forest maps I carried and provided—free of charge in those days—to the public. Assistance to visitors in emergencies, it goes without saying, also was part of the job.

I often wondered just how I was doing at the job. It didn’t seem enough to be told I was doing a good job. I had questions that wouldn’t answer, questions I had to answer for myself. Was my approach to each situation a good one? Did each face-to-face encounter reflect the right mix of diplomacy, empathy, and helpfulness? Was my image one of fairness and competence? Just what kind of impression did I leave with the public? It seemed I was in a position to make good friends or bad enemies for the Forest Service on a daily basis.

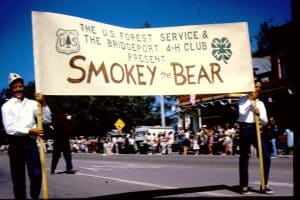

Did I worry too much about such things? No, I decided, I didn’t. My job was more than preventing and suppressing forest fires. It was also to win friends for and understanding of the Forest Service and its endeavors. The way I did my job helped mold public opinion of the organization in which I had always wanted to serve.

That’s why I had to be careful. It’s all too easy for someone whose job involves daily contact with a variety of publics—in my case, a wide range of national forest visitors and users—to forget these things, to become indifferent toward or even disdainful of the publics he or she serves. Worse yet, I knew, would be to ape the “badge-heavy” cop or act a “big shot” around these publics.

After all, these visitors and users are the citizen-owners of the National Forest System. It’s “national forest land” that belongs to the people of the United States and is administered for them by the Forest Service, not “Forest Service land.” A small point? A nit-pick? Not at all! It’s an all-important distinction that informs—or should inform—the perceptions of both the public servants and the publics they serve of their respective roles, responsibilities, and prerogatives regarding the national forests and each other.

Although most of the people I met were middle-class California suburbanites, visitors to the Toiyabe National Forest came from all parts of the nation and the world. All deserved the best and friendliest service I could provide. I learned then, and believe still, that pubic service means just that.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.