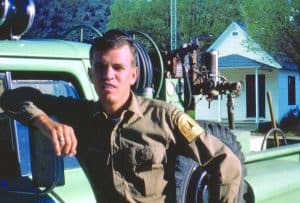

When a fire prevention guard spots or gets a report of a smoke, he’s temporarily out of the fire prevention business and in the fire suppression business. (Yep, I staged this photograph using smoke from a Forest Service dump!)

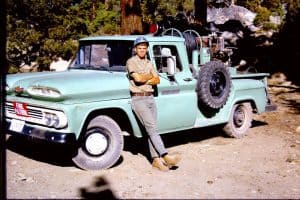

On July 22, 1963, with not a fire on the Bridgeport Ranger District yet that summer, my fire prevention job of the day was hazard reduction. Don, a new fire crewman, and I were clearing cheatgrass at strategic locations along the Buckeye Road to remove flash fuels that could carry fire into the canyons.

At about half past noon, and halfway through our lunch break, a carload of fishermen, speeding along the road toward the ranger station, honked to a stop to report “a big fire running up the mountain near Eagle Creek!”

Don and I were in the fire rig and on the way in seconds. As I radioed the four-eleven—emergency fire call—to the ranger station, it occurred to me that this fire was man-caused. There hadn’t been a lightning storm in weeks.

We arrived at the fire about the same time the fishermen reached the ranger station with their exaggerated report. I sized up the small blaze burning in brush under a few Jeffrey pines near the old Buckeye Pack Station and cranked up the pumper.

Then, as Don attacked the flames with water, I hit the radio. Fire Control Officer Marion Hysell, on the strength of the fishermen’s report, had just ordered an air tanker. I advised my boss we would soon have the fire under control and to cancel the air show. The fire was knocked down in minutes. Marion drove out to check up on us, and helped us mop up.

We thought there was something fishy about the fishermen’s report of this “big fire near Eagle Creek” that wasn’t, but had nothing other than that mere hunch on which to go.

The flash fuels cured as expected, and the district’s fire danger remained high most of the rest of the season. But, even after many August lightning storms, that small man-caused fire somehow remained the only fire of my first fire prevention guard fire season.

The district wouldn’t always be so lucky.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.