Here’s a Colorado Sun story..

Here’s a Colorado Sun story..

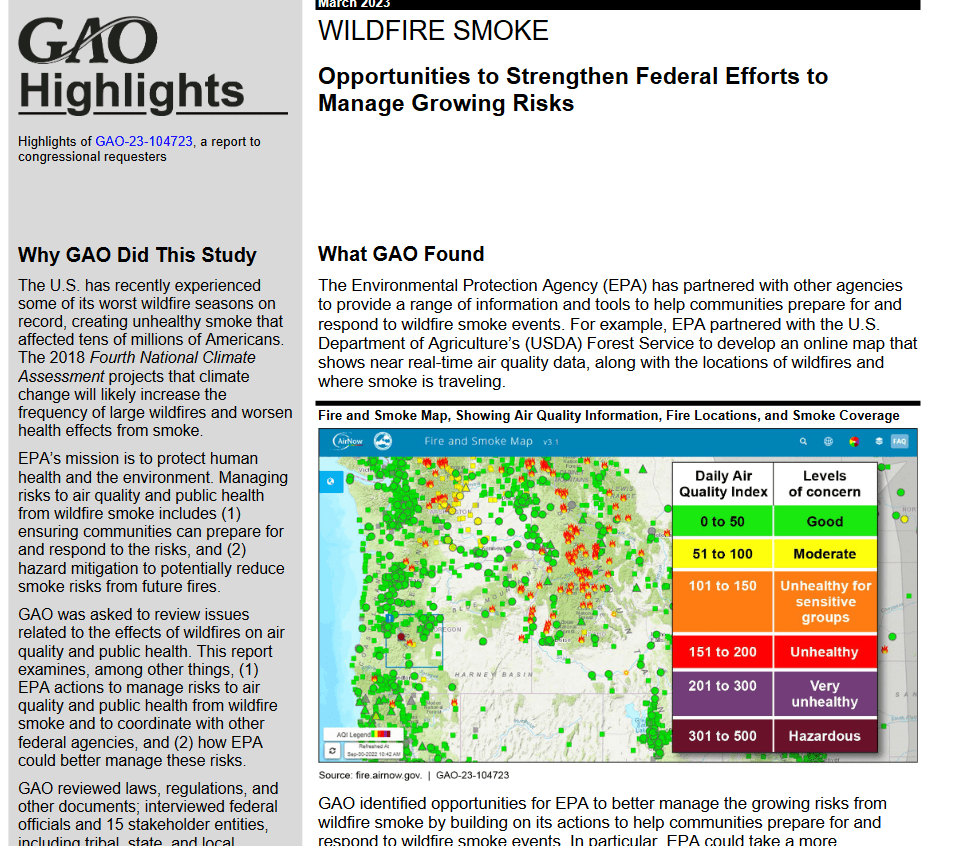

This is about non-wildfire air pollution (ozone), but to my mind doesn’t make a strong case for EPA regs making sense. And of course, EPA uses maps with un-groundtruthed wildfire risks directly from an outside group, so there’s that, and their lack of coordination with other federal agencies on wildfire smoke… I’m not picking on them as an agency, but like the FS and BLM I’m sure there are things they are doing well and others not so well.

The EPA’s justification for the new good neighbor rulings, published in the Federal Register, says the agency’s well-established monitoring methods show Utah contributing more than the 1% threshold of regulated substances to other states. “Its highest-level contribution is 1.29 parts per billion to Douglas County, Colorado,” the EPA said.

That number appears small, but the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission and the Regional Air Quality Council spend countless hours discussing strategies and policies to potentially shave a part or two per billion off summer ozone levels in the Front Range nonattainment area. Readings in recent summers have spiked above 80 ppb at some monitors.

At first, when I read this article, I was curious about the justification for 1%. It seems fairly, well, minimal.

Unfortunately, we don’t get to hear Utah’s side of the story because.. they are in litigation.

Colorado hasn’t joined in on the litigation despite pressure from environmental groups to support EPA (in blaming other states for our Colorado-generated problems?).

From a CPR story (that also talks about the relationship between ozone and wildfire smoke):

In 2014, Flocke and his NCAR colleague Gabriele Pfister conducted a state-commissioned aerial survey to track the ozone sources along the Front Range. The research found that the region has background ozone levels of about 40 to 50 parts per billion, which is short of the current federal health standard of 70 parts per billion.

Local emissions of air pollutants pushed air quality to unsafe levels. On days when ozone levels exceeded federal health standards, traffic and oil and gas combined are responsible for more than two-thirds of ozone production along the Front Range.

Colorado’s ozone landscape has likely changed in the seven years since the survey. Energy companies have installed more pipelines, cutting down on total emissions from oil and gas production. Over the same period, more people have arrived in Colorado and brought their cars with them. While the COVID-19 pandemic led to a reduction in Front Range traffic in the spring and summer of 2020, Pfister said state data show it has rebounded to record levels in Denver.

“There are basically just more cars on the road,” Pfister said.

When I first read the Colorado Sun story, I was puzzled by the mechanics of how pollution from Utah could fly over the western part of the state and lodge in Douglas County. A wise reporter friend suggested that perhaps Douglas County is in non-attainment, so the percentage is equally low in other counties, bu it doesn’t matter for them. This would make sense. I reached out to the reporter for the more information and name of his EPA contact but haven’t heard back.

Anyway, it seems like ozone is fundamentally an urban problem on the Front Range.. so why go after rural folks in Utah?

As it turns out, this came up last year in Wyoming, via the Cowboy State Daily.

The EPA, in an April 6 report, said Wyoming contributes up to 0.8 parts per billion to the Denver-Chatfield area “smog” — just more than 1%.

As a result, the agency wants to enact its “Good Neighbor” mandates that would allow it to place tougher greenhouse gas restrictions on Wyoming and several other states which contribute 1% or more to ozone pollution in “downwind” states.

The EPA early this month deemed the Denver-Chatfield area a “severe” violator of federal ozone, or smog, standards – a downgrade from its prior status of “serious” violation.

**********

Gov. Mark Gordon in a March statement called the “Good Neighbor” mandate an “attack on state-led approaches” moving “more authority away from the people to Washington, DC.”

Gordon also said the plan targets Wyoming and other Western energy-producing states, and seeks to penalize their energy industries.

“It will harm states like Wyoming who meet ozone standards and benefit more populous states that use our energy but do not meet their own standards,” Gordon continued. “EPA’s proposal does not ‘follow the science’ or the law and will unjustly discriminate against Wyoming industries.”

**********

The Cowboy Daily also raises the question about California..

In the same projection, California was expected nearly to double Wyoming’s chemical share of Colorado’s smog by contributing about 3 parts per billion to Colorado.

California also is expected to export about 40 times Wyoming’s ozone-chemical output nationwide, with 34 ppb total ozone-chemicals export.

And then there is this interesting critique of the EPA modeling from a Colorado engineer (yes, ozone is measured but of course, contributions are modelled), also from the Cowboy State Daily.

This is just one piece of the critique:

“EPA states that the average difference between the projected values and the actual values is 7.79 ppb (parts per billion of ozone-contributing chemicals),” reads Strobel’s letter to the governor.

Wyoming’s likely inclusion in the “Good Neighbor” restrictions is due to its projected 0.81 ppb contribution to Colorado’s total ground ozone, which is projected to be 71.7 ppb in 2023.

“If the model cannot project values with any more accuracy than 7.79 ppb for Chatfield,” wrote Strobel, “it is absurd for EPA to suggest that they can project that 0.81 ppb will come from Wyoming.”

If Wyoming’s projected contribution had been below 0.7 ppb, the state would not fall under the “Good Neighbor” restrictions.

“With such poor accuracy,” continued Strobel, “it is also absurd for EPA to claim that they can distinguish between 0.81 ppb and the 0.7 ppb threshold for requiring action.”

If you’re curious, you might wonder why Colorado isn’t a bad neighbor to Kansas.. it seems probably as there are no large urban areas in non-attainment.

It’s perfectly normal for federal agencies to find rationales to expand their power over states. But this one seems a little arbitrary and dare I say, capricious. A person could even wonder whether the political inclinations of the “bad neighbor” states have been somehow factored in..