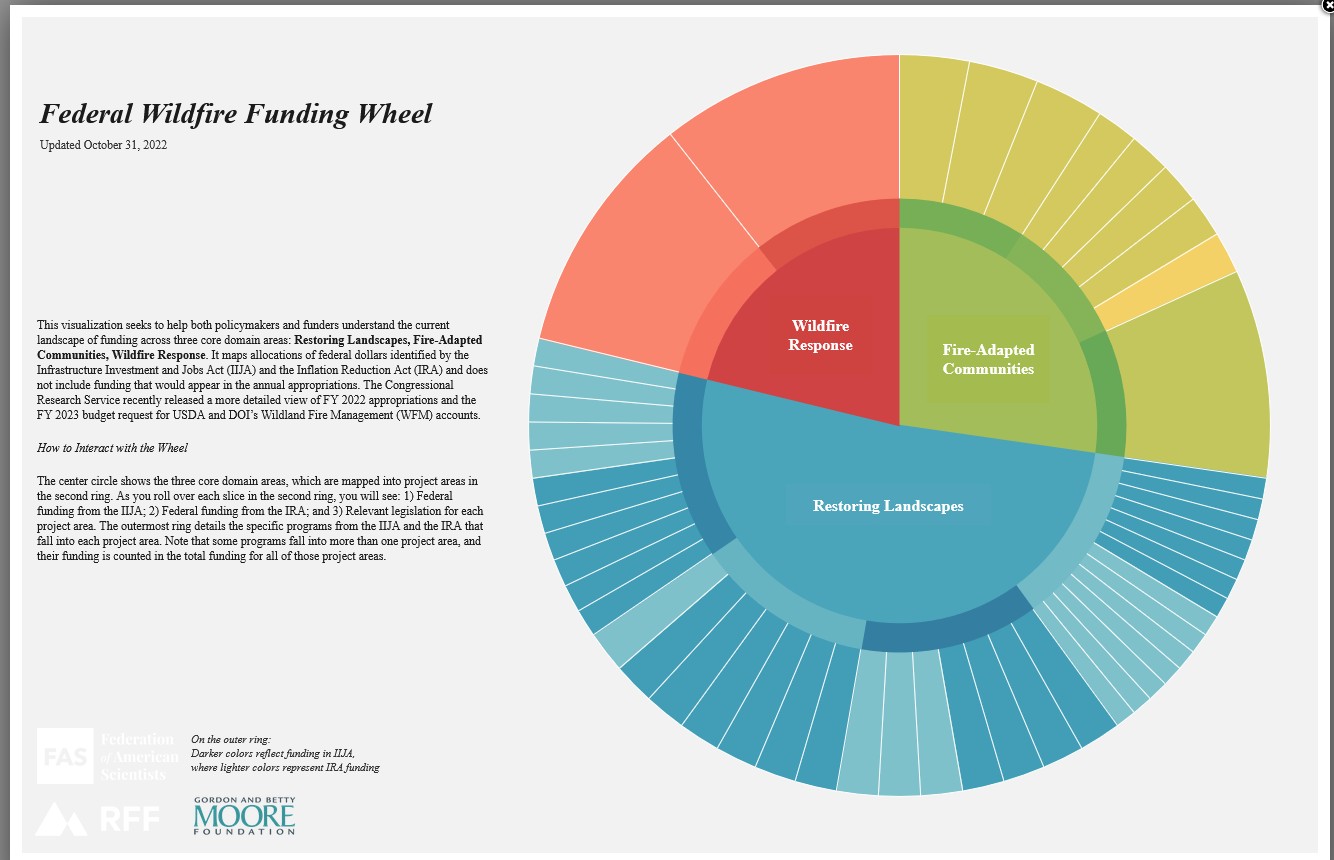

This is a pretty cool thing developed by the Federation of American Scientists, Resources for the Future, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. If you click on the link (not the photo above) you can see all the different programs. Lotsa bucks.

Sharon

Inventory of Environmental Permitting Tools

The Forest Service and BLM are part of “permitting world,” so while this is a little NEPA-nerdy for TSWites…

I ran across this application inventory from the Federation of American Scientists , their idea being to:

“survey permitting tools for interested users, open up lines of dialogue for cross-application learning, and highlight where we see needs for further permitting tech investment. ”

It’s pretty interesting to look at the federal lineup of apps.. I didn’t know that EPA has all EISs since 2012 online (of course, I retired in 2012); also CEQ has a comprehensive list of all CEs. Hopefully the descriptions of FS and BLM apps are accurate.

Litigation Settlement in Montana and Social Justice Concerns

While this is normally Jon’s bailiwick, this settlement is of particular interest. Here’s the article from the Daily Montanan, without a paywall.

This story describes a settlement of litigation on a project in Montana. It would appear to an outsider, and by Garrity’s own claims as reported (I bolded below), that their organization’s views had an outsized role in determining on-the-ground specifics of projects. Once again, the way it works is that DOJ gets credit for settling..the Forest Service gets credit for doing things, so it appears that different federal agencies have different goals. For folks relatively new to TSW, I wrote a post in 2011 on Chief Jack Ward Thomas’s experience at being overruled by DOJ:

The Department of Justice is, in my opinion, almost always too eager to settle legal actions, particularly when plaintiffs are of the environmental persuasion. It was a shock to my system to find that the Department of Justice does not consider the Forest Service a client. They have little concerns as to the desires of the Forest Service or any other agency. They set their own course and in doing so are de facto setters of policy. Somehow that seems to be a serious flaw in the system. But for now, at least, it is the system.

Now I don’t have any insider information about this particular settlement, so perhaps this was not the case with this one. From the news article:

Under the agreement, accepted by federal district court Judge Dana Christensen, the United States Forest Service can still move forward with aspects of the massive plan, including the Crouching Trout Timber sale, which authorizes nearly 25 miles of temporary or current road construction. The Crouching Trout timber portion covers approximately 1,600 acres.

Originally the project touched three Montana counties — Lewis and Clark, Meagher and Broadwater counties — and called for more than 53,000 acres of tree cutting and burning, 6,669 acres of commercial burning, and 45,934 acres of burning, plus more than 100 miles of road building. The groups had argued in federal court that the project was illegal and could disrupt critical habitat for several species.

The project was originally slated as a 20-year project in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest and the Big Belt Mountain Range.

As part of the agreement, the Forest Service can continue with the “associated activities” in the Crouching Trout Timber sale. The service also agrees to limit prescribed burning to the “inventoried wilderness areas” of no more than 25% of any area.

The U.S. Forest Service also agreed to produce annual summaries of the prescribed burning in the Middleman Project, “including units where burning has occurred and the acres burned.”

The U.S. Forest Service also agreed to a $39,000 lump sum payment to settle claims of attorneys’ fees.

Previously, the conservation groups had argued that the central Montana land was a key part of grizzly bears’ habitat and made it easier for “genetic exchange” between the populations of Yellowstone and Glacier National Park areas.

“We are thrilled that the Forest Service agreed to settle this case,” said Mike Garrity, executive director for the Alliance of the Wild Rockies. “We stopped over 100 miles of road construction and reconstruction in the forest, and we stopped over 5,000 acres of commercial logging in lynx and grizzly habitat.”

I’ve looked at the Board of Alliance for the Wild Rockies and they seem like nice people. There appear to be two Montanans, a Utahn, and an Idahoan. It’s not clear to me who funded the lawsuit.

Here’s a link to their 990. It looks like the source of their funding is restricted, but maybe I’m reading it wrong.

My point is not that folks shouldn’t have views. It’s not even that rich people shouldn’t fund whatever they want, through the processes like 501c3s and c4s, that we have in this country.

My point is about justice. Some people’s views count much more than others, apparently. Possibly people (funders) who have never set foot in Montana. They are not political folks who have some accountability to the broader (Montana) public via elections. We can’t even examine their diversity in the terms we usually use.

As far as we know, they (nor the DOJ) folks haven’t read nor considered public comments on the project.

I haven’t mapped the project itself, but certainly parts of Lewis and Clark County are identified as disadvantaged in the CEQ Climate and Economic Justice screening tool. So I guess there is an environmental justice perspective as well. We need to listen to the voices of those communities, and that’s a major push for this Administration.. but they were not in on the settlement discussion. Maybe this is another case in which agencies are not aligned.

Interestingly, AWR has a page about its supporters. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse from Montana, Reps Raul Grijalva from Arizona, Carolyn Maloney from New York, Jimmy Carter, Carole King (Montanan), and Gloria Estefan.

Now, I’ve heard the argument that they are federal lands, and so anyone across the country should have an equal vote on what happens.. as one EPA senior executive said to me “an apartment dweller in New York should have an equal voice to a resident of Delta” (we were in Delta, discussing a project on the GM).

I call that the “property rights” argument. But this is not that.

Funders we don’t know, from where we don’t know, whom no one elected, are effectively setting policy for a piece of the country, with those policies having an outsized influence on local residents. Their intentions are noble. I agree. But noble intentions combined with political power don’t always work out so well for ordinary people, as some of us older folks recall from 20th century history.

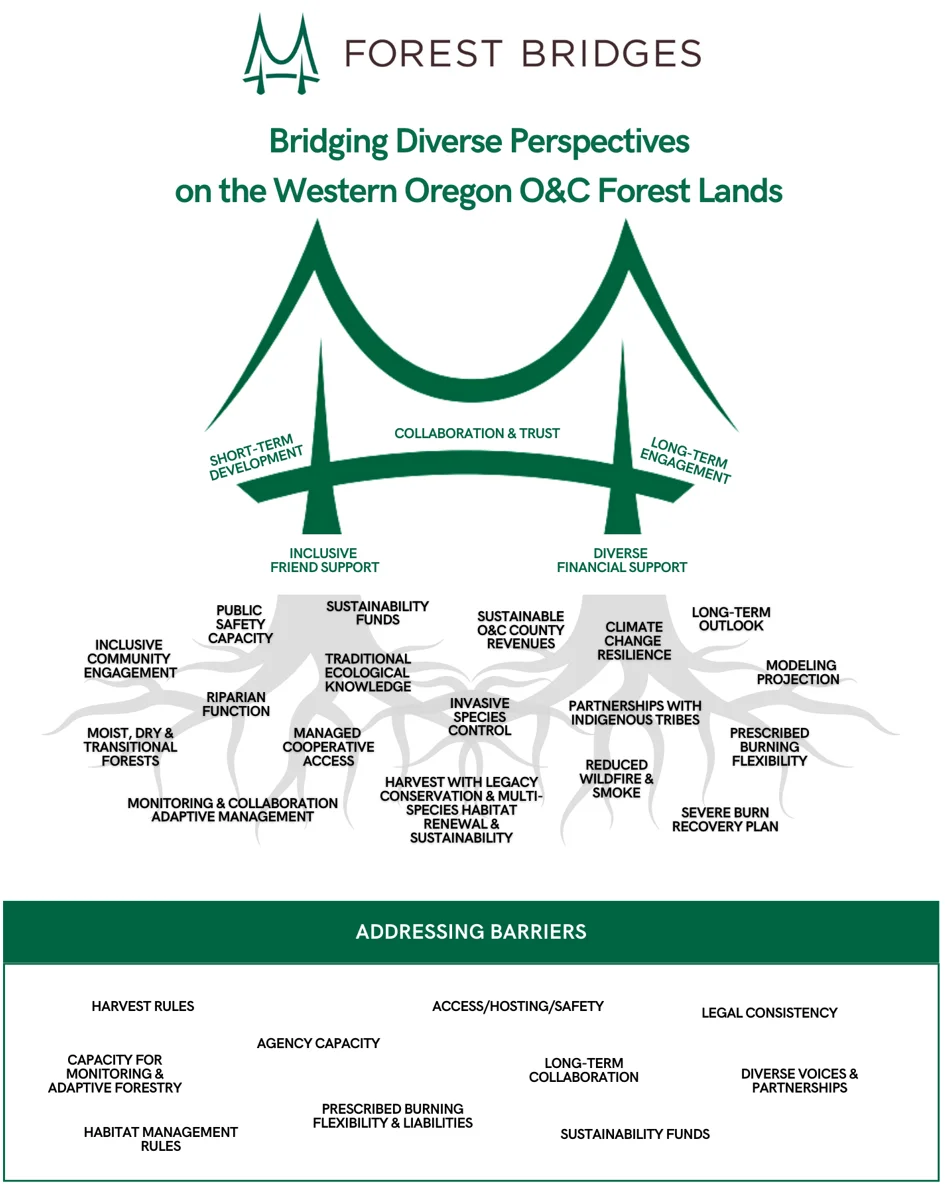

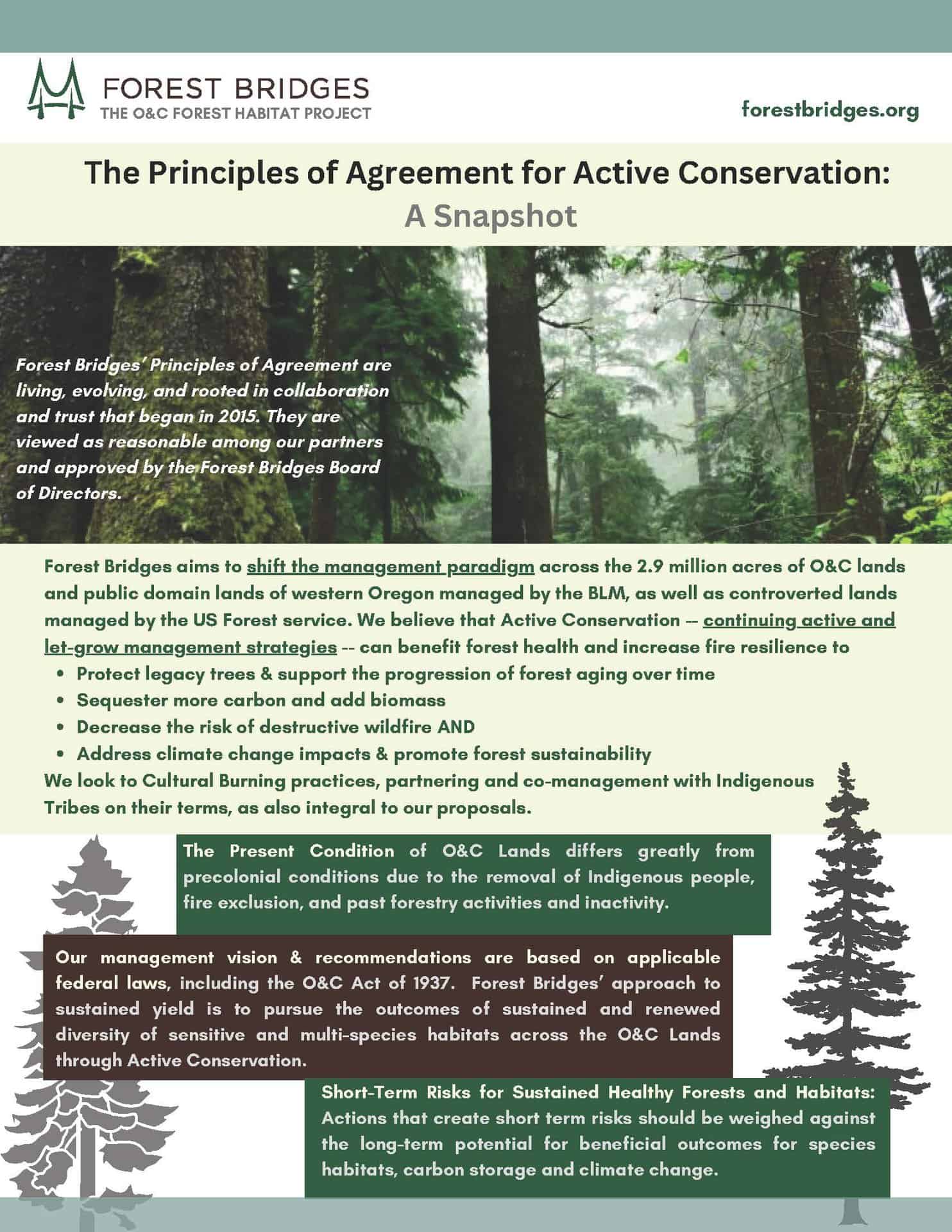

Forest Bridges: Working Toward Agreement on O&C Lands

I’m always interested in people seeking agreement about forest issues, and Oregon seems to be a long-time source of ongoing controversy. Thanks to Nick Smith for this one.

I’m always interested in people seeking agreement about forest issues, and Oregon seems to be a long-time source of ongoing controversy. Thanks to Nick Smith for this one.

There was an interview on Jefferson Public Radio, but I couldn’t find it. Here’s the description.

The so-called “O&C lands” of Western Oregon have long been a focus of contention. They are lands once given by the federal government to the Oregon & California Railroad (O&C), taken back by the feds, then managed under law by the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The bone of contention comes from the sharing of timber receipts from those lands with the 18 O&C counties, which puts pressure on those lands to produce timber.

The nonprofit Forest Bridges proposes bringing the multiple sides of the debate together, to agree on timber cutting methods, and–more importantly–which land to include in the timber base. Forest Bridges Executive Director Denise Barrett gives us an interview with an overview.

Forest Bridges has a good website with lots of info. Their Principles of Agreement are here.

Below is a snapshot of their principles of agreement. Feel free to discuss anything on the website in the comments.

Below is a snapshot of their principles of agreement. Feel free to discuss anything on the website in the comments.

Traveling Critters: Toads, Suckers and Cougars, from the Utah Wildlife Migration Initiative

From the Utah Wildlife Migration Initiative:

1000 Mile Journey of Cougar F-66

She completed 1,000 miles in less than 165 days, averaging 6 miles per day — with some days exceeding more than 20 miles of travel! Once up and over the Rocky Mountains, she continued her journey east, crossing 75% of the state of Colorado before her death on Nov. 13, 2022. In conjunction with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, a biologist and wildlife veterinarian determined she had been killed by another cougar.

“Around 220 miles into her journey, on July 4, 2022, F66 sat on the banks of the Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Wyoming. At that point, F66 could either turn around and return north, or plunge into the cold water and move forward.

Hinton said F66 made the shocking decision to swim at least a quarter of a mile to reach the other side of the reservoir. From there, she continued her journey south.”

Video of Boreal Toad Journey

Tracked toad went five miles across rocks and desert.

Razorback Sucker Migration Animation: hatchery sucker’s nearly 1000 mile journey over dams and through reservoirs.

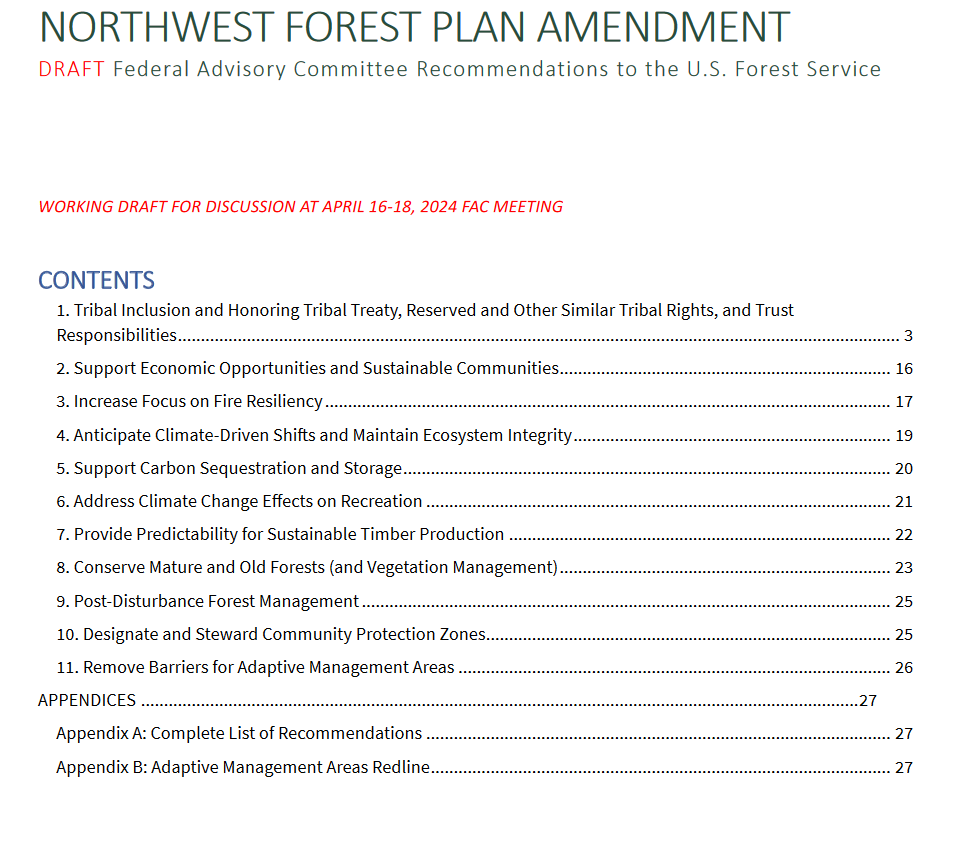

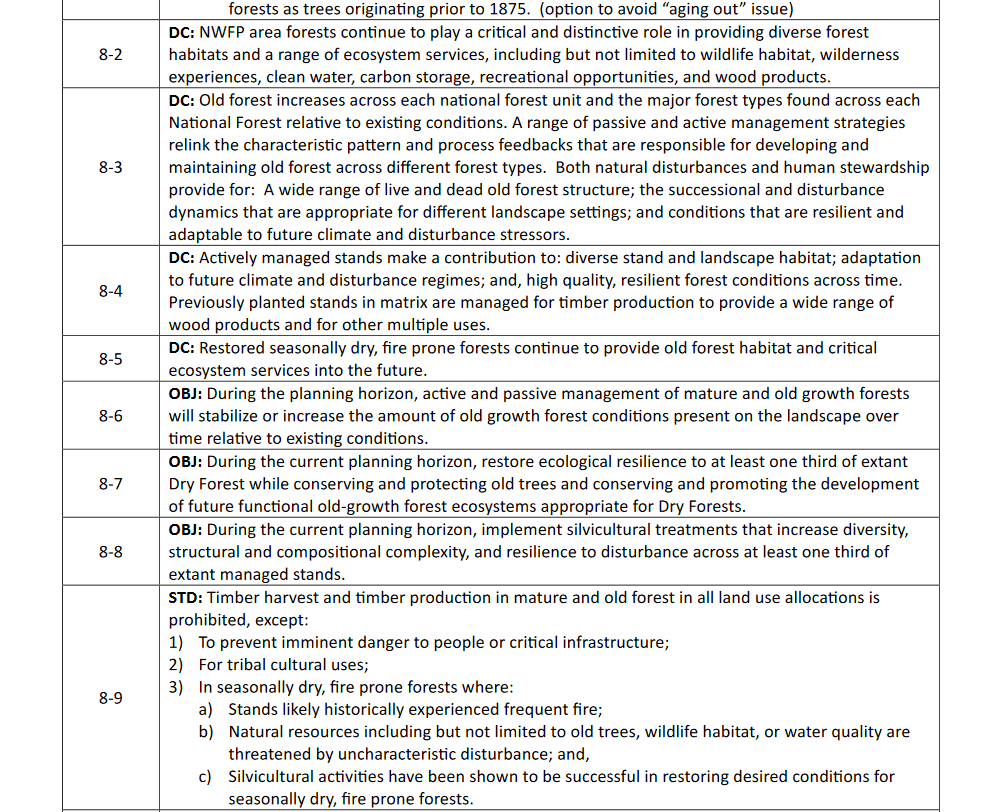

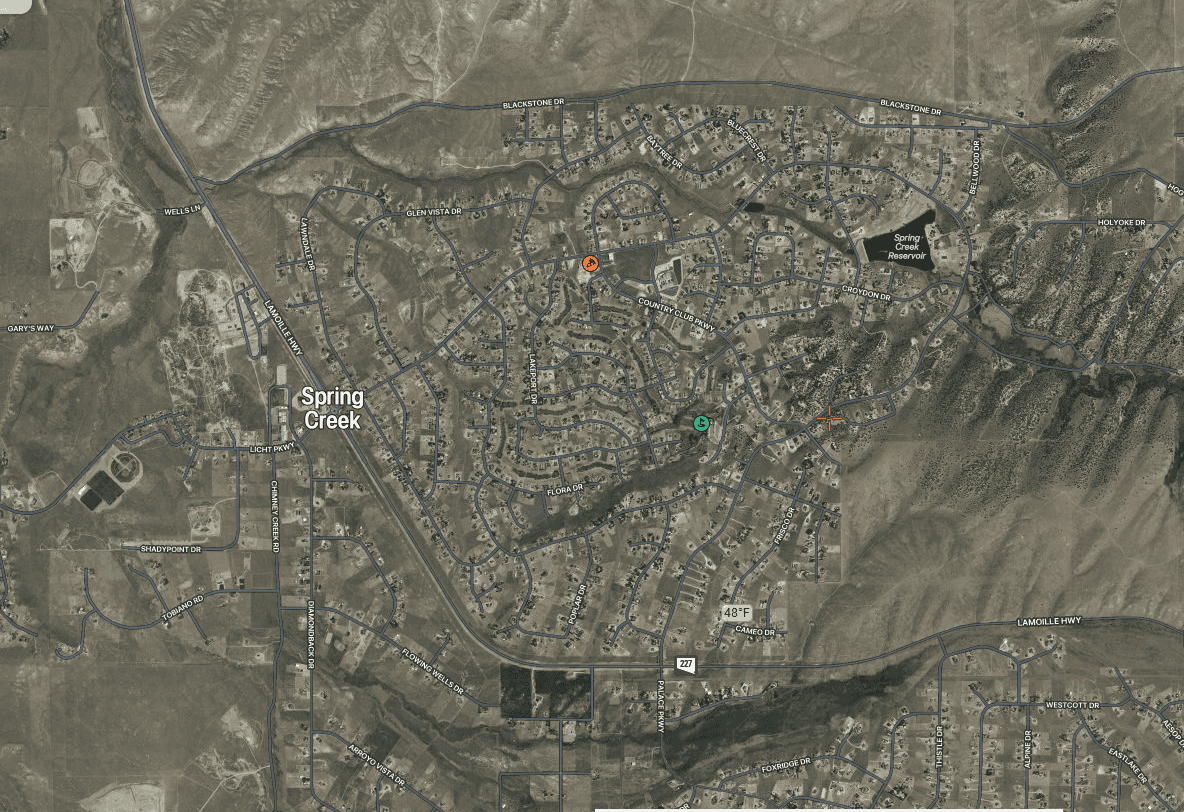

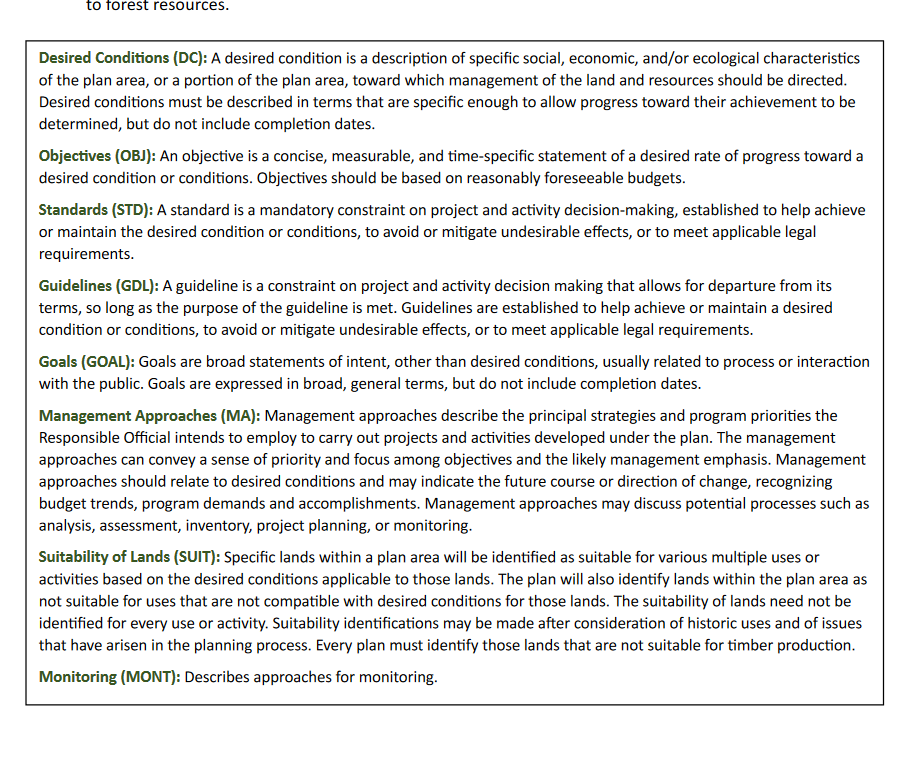

Northwest Forest Plan Amendment- FACA Committee Discussion Draft Plan of Components

Susan Jane Brown was kind enough to provide links to the draft plan components and draft recommendations. She pointed out, importantly (!) that “THESE ARE DRAFT AND UNDER ACTIVE DISCUSSION AND NEGOTIATION. The USFS hasn’t made any decisions yet, nor has the FAC reached consensus.” Here’s a link to their meeting archive page, and here’s one to the recommendations.

As with many things in forest planning there are many words here, the Tribal recommendations are too long to post, 15 pages and change.

So I hope readers will take a look and give us your thoughts on any section. Maybe our thoughts will help inform the FACA committee and the Forest Service? I’d like it if they would not use “resiliency” and always use “resilience” but that’s just me.

Here are plan components for those not familiar with the planning process:

Here are the different sections for you to look at.

Here are the different sections for you to look at.

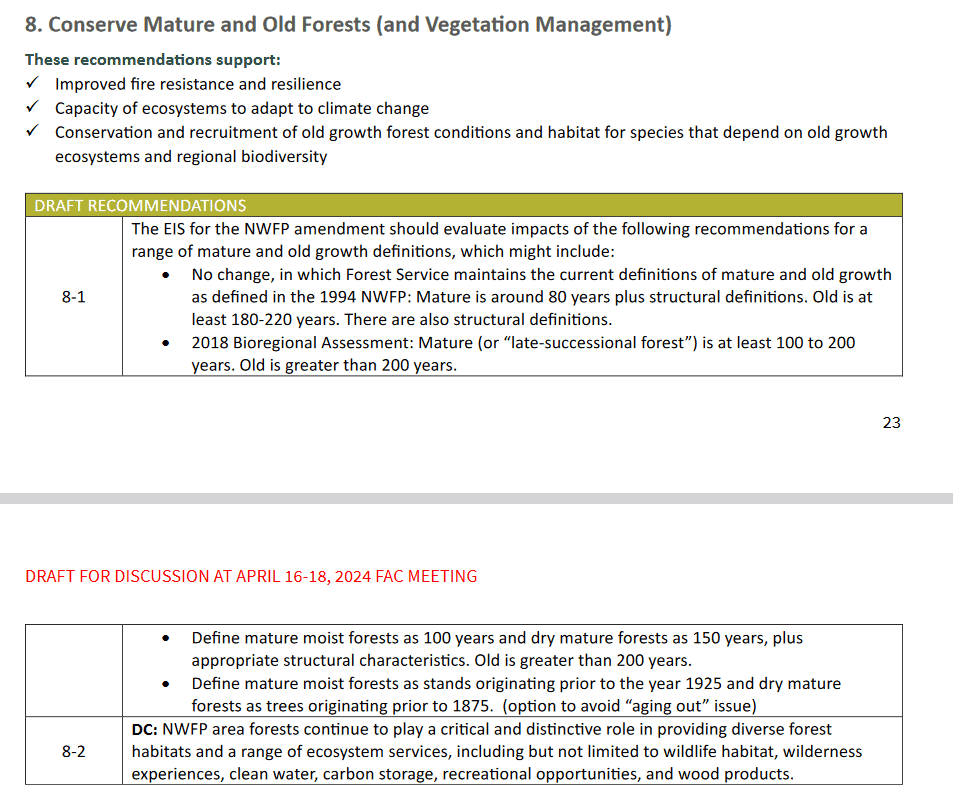

Here’s a section some might be interested in (I picked it because it is relatively short):

More on the Hiring Pause That May or May Not Refresh

This is the latest I received from one of my sources..

I asked the question “so it’s the folks covered in FF retirement and who have fire quals that are not being affected?”

Also I got an answer as to “why it’s so hard to count.”

It does get a little fuzzy around the edges. Clearly fire positions with FF retirement coverage are not in any kind of pause. Right now, even some fire-funded positions such as Fire Cache positions are not affected. No current non-fire employee is impacted except in terms of applying for a position for competitive promotion and/or lateral…opportunities may decrease as vacant positions are held vacant due to funding concerns.

Figuring out how many vacancies are out there in the process of being filled is not that simple. For a lot of hiring, for various reasons, an SF-52 is no longer submitted to initiate a hiring action, and is only generated and entered into the system once a tentative selection is made. This cuts down on a tremendous amount of unnecessary front-end work when for whatever reason a hiring manager ends up not making an offer. Intake portals have replaced the early submission of 52s in these scenarios. Also, hiring managers are doing more backfilling at the same time they are selecting for vacancies, so there are often additional hires being done that were not listed in the initial portal inventory. Bottom line is there is no one system to accurately account for how many hires are in process, and no way to quickly assess this, hence the “pause”.

Anyone with more information, please weigh in.

Northern Region Update April 2024

Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Other Regions, if you send I will post.

If You Build it, Wood Will Definitely Come: Chelan Develops “Wood Products Campus”

Chelan County is moving ahead with plans for a wood products campus, which would use timber thinned from the county’s forest land to make a variety of wood products.

County commissioners and staff recently toured sawmills and biomass plants in the region to gather ideas for the future facility.

Chelan County Natural Resources Director Mike Kaputa says they’ll look to develop a hybrid type of plant, based on what they saw.

“I wouldn’t say that we saw any one facility that we thought was perfect for Chelan County, but some combination of those things we think is going to be perfect for Chelan County,” said Kaputa. “So, we have a lot of ideas, and we have a lot of partners that are working with us on this, so we’re going to be looking into this very seriously over the next few months.”

Among the stops the commissioners and staff made were in Colville and Wallowa, Ore.

In Colville, they toured Vaagan Brothers Lumber, a company started in the 1950s and today is a leader in the west in sustainable forestry.

In Wallowa, they toured the Heartwood Biomass facility. Heartwood takes wood that is underutilized by the traditional logging industry and turns it into various wood-based products.

Kaputa says they’ll be working to figure out what products can be derived from the Chelan County forest and what type of facility needs to be built.

“We’re going to be talking about, given the work that’s going to occur on the national forest here over the next five to 10 years, what are the best product lines that we think could come from that, and then what kind of infrastructure do we think we could bring here to support that,” Kaputa said.

He said the county has spent two years coming up with several assessments of the wood supply and the different product lines that could come from that wood supply in the forests of Chelan County.

Kaputa said some type of facility will be in place to serve as a wood products campus in two years. He said the price tag would be between $15-$20 million to build the facility and/or convert existing buildings into one of more plants.

He said funding could come through several sources, including county economic development sales tax collections as well as state partners and the forest service itself.

The county has a good neighbor authority agreement to with the forest service to go into the Okanogan Wenatchee National Forest and conduct the work to thin the forest.

The process of thinning the forest of excess timber and using the wood to produce useful products – lumber for building purposes, firewood, poles, wood chips, etc. – would help achieve the goal making the forest healthier and protecting it from wildfires.

Kaputa said the forest land in Chelan County needs held because the decline of the forest in the county is well documented and the need for treatment is well known and well documented.

“Chelan County is the highest risk community in the state for potential wildfire damage,” said Kaputa.

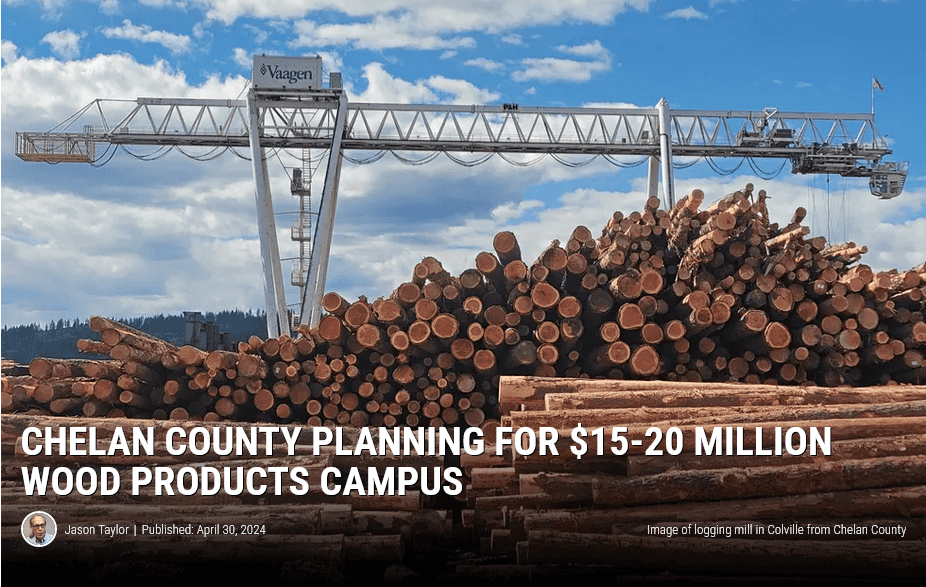

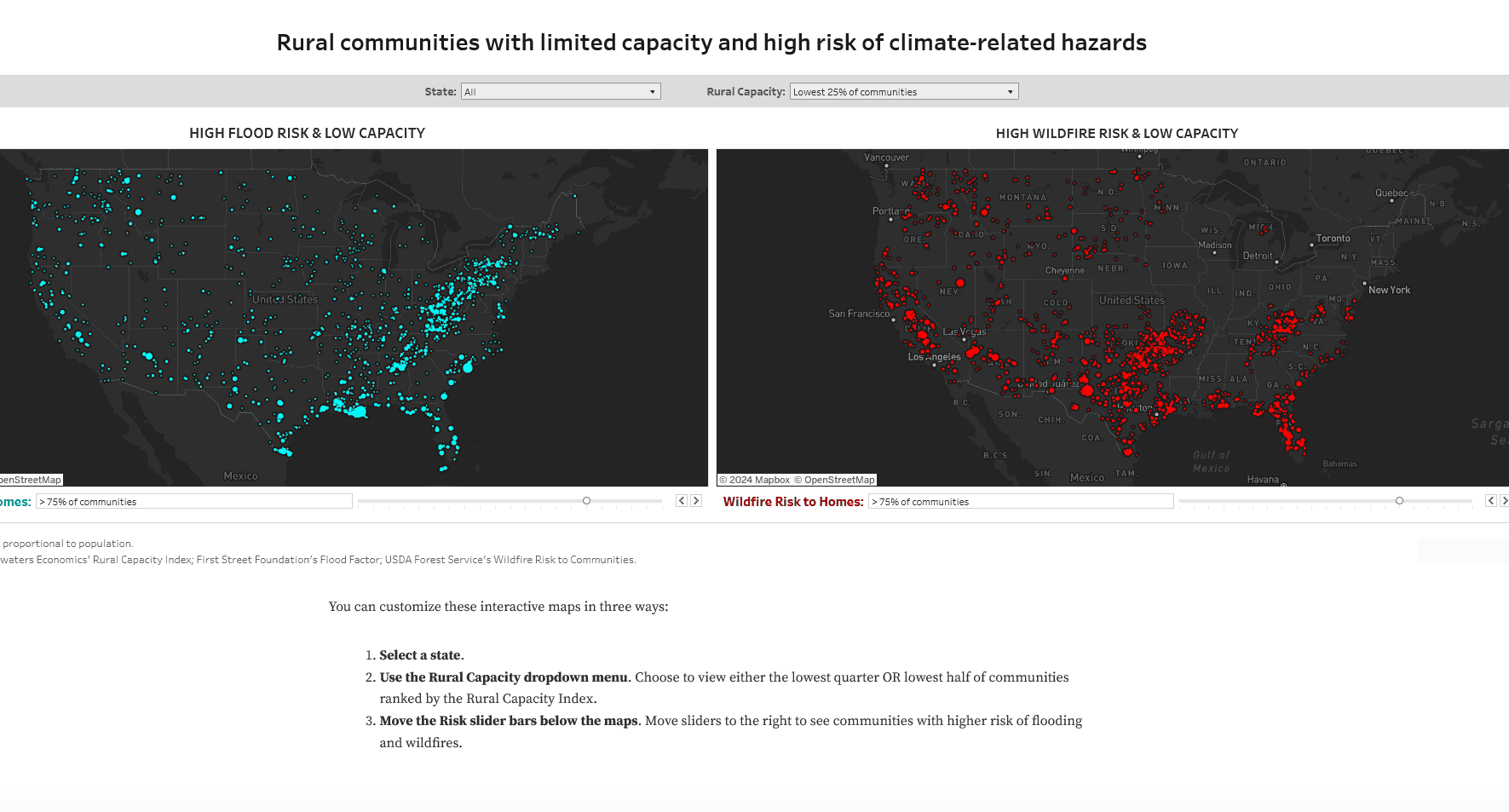

Let’s Groundtruth: Headwaters’ Rural Capacity Map

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

| Rural Capacity: | 50 out of 100 |

| 13th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 100th percentile in the U.S. |

So I wondered what the landscape looked like for an area with the 100th percentile for wildfire risk.

This is not a critique of Headwaters, as they used the Forest Service’s (and not First Street’s) Wildfire Risk to Communities map.

I think groups who develop maps think that they will be useful. But I don’t know. It seems like these maps don’t always directly address the problem at hand, in this case, “does a community have hired or volunteer folks available and knowledgeable to apply for federal grants?”. I know some communities who don’t.. even though conceivably the area is generally fairly well off. Maybe another solution would be to make the federal granting procedures easier to understand. I have friends with high capacity who find the processes of applying for grants for wildfire mitigation in their communities to be more difficult and confusing than needs be.. plus State requirements for fed bucks transferred to the State. It would be interesting for the Forest Service or someone else to commission listening sessions for communities on their tribulations in acquiring funding, coordinating different programs’ requirements, and so on. Maybe someone has.

Anyway here’s the link.

The sliders (the default is 50%) for the flood and wildfire maps are really important. Here is Moab, Utah, which we might think is fairly well-disposed in terms of economics.

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 21st percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 62nd percentile in the U.S. |

If you go up to 80% of communities, you can find a place like Pagosa Springs

| Rural Capacity: | 49 out of 100 |

| 12th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Or a community in my own area, Ellicott, CO

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 20th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Now Ellicott is, for all practical purposes, a bedroom community for Colorado Springs in El Paso County, which is fairly well off. And county folks would be staffed to help communities apply for grants. But are they? Isn’t that the real question? Then there’s the question of what folks in Ellicott would actually do with the grant money, since it’s a grassland. Plan evacuations? Is Ellicott-only the right scale for that?

Communities need capacity—the staffing, resources, and expertise—to apply for funding, fulfill complex reporting requirements, and design, build, and maintain infrastructure projects over the long term. Many communities simply lack the staff—and the tax base to support staff—needed to apply for federal programs. Communities that put together applications are often outcompeted by higher-capacity, coastal cities. The places that lack capacity are often the places that most need infrastructure investments: places with a legacy of disinvestment including rural communities and communities of color.

Places that receive the most external funding – whether from state and federal programs or philanthropy – often have larger staff, more expertise, and deeper political influence, not necessarily greater merit. Communities that need the most assistance may be the least likely to even submit applications. For the United States to fully adapt to climate-driven threats and bolster aging infrastructure, its programs and policies must account for community capacity.

Where is capacity limited?

To help identify communities with limited capacity, Headwaters Economics created a new Rural Capacity Index. The Index is based on 12 variables that can function as proxies for community capacity. The variables incorporate metrics related to four categories of capacity: local government staff and expertise, institutional capacity, economic opportunity, and education and engagement. (Read more under Data Sources and Methods below.)

Results are available for counties, county subdivisions, communities, and tribal areas in the interactive map below. The tool displays data across the urban-to-rural continuum to illustrate the variability in community capacity across the country. The inclusion of metropolitan communities is necessary to show the comparatively lower capacity that exists in most rural communities.

Why not- call places that low on the economic scale and ask them what their barriers to applying for federal grants are? For some, being in the 100 years flood plain may not be a concern.

Anyway, their conclusions seem fairly straightforward.

Supporting communities

To achieve the infrastructure and climate adaptation goals in federal programs, funding agencies must consider community capacity. Programs may need to be structured differently and new strategies may need to be created to support under-served and historically disinvested communities.

Using the Index, community capacity can be supported in many ways:

- Provide direct funding. For communities with low Index scores, eliminate the need for competitive grants, which many lower-capacity communities lack the resources and expertise to apply for and administer. Federal and state programs can identify where the needs are greatest and allocate funding accordingly.

- Improve access to competitive grants.

- Allow funding to be used to build capacity—not just used for projects. For example, funding could be used for new staff positions and technical training to support long-term investments.

- Eliminate or reduce match requirements. City and county budgets in low-capacity communities may not have the revenue to meet matching requirements.

- Revise requirements for benefit-cost analyses. These technical reports are expensive and highly technical. They often undervalue the benefits of projects in lower-capacity and lower-income communities.

- Fund technical assistance. Administered by state or federal agencies or by nonprofit partners, technical assistance programs provide expertise in project identification, design, and implementation, as well as assistance in compiling grant proposals.

- Increase funding for multi-jurisdictional projects. Funding regional projects that leverage urban-rural partnerships can benefit low-capacity communities. This may require investment in regional institutions and organizations that can help coordinate resources and prioritize projects.

- Address root problems. Low-capacity communities are often economically dependent on farming and other natural resource sectors associated with volatile revenue. By strengthening policies that encourage economic diversification, state and federal policymakers can help communities generate predictable local revenue needed for infrastructure and adaptation.

On the other hand, rather than hiring more people to interpret ever-more complex programs, or regionalizing them out of the community’s direct authority (via “urban-rural partnerships”), how about considering simplifying requirements at the front end.