Dr. Beverly Law recently gave a presentation titled, “Role of Forest Ecosystems in Climate Change Mitigation.” Here’s some information on Dr. Law’s background, education and area of expertise, via

Dr. Law’s website at Oregon State University:

Dr. Beverly Law is Professor of Global Change Forest Science in the College of Forestry, and an Adjunct Professor in the College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University. She is an Aldo Leopold Leadership Fellow. Her research focuses on the role of forests, woodlands and shrublands in the global carbon cycle. Her approach is interdisciplinary, involving in situ and remote sensing observations, and models to study the effects of climate and climate related disturbances (wildfire), land-use change and management that influence carbon and water cycling across a region over seasons to decades. She currently serves as the Chair of the Global Terrestrial Observing System – Terrestrial Carbon Observations (supported by UNEP, UNESCO, WMO), and on the Science/Technology Committee of the Oregon Global Warming Commission.

You can view a PDF copy of Dr. Law’s presentation right here. Below, the text-only version of Dr. Law’s presentation does a nice job of summarizing the myth and reality regarding “thinning,” bioenergy/biomass and climate.

Role of Forest Ecosystems in Climate Change Mitigation

B.E. Law – Oregon State University, February 23, 2014

Key Points:

Activities that promote carbon storage and accumulation are allowing existing forests to accumulate carbon, and reforestation of lands that once carried forests.

Natural disturbance has little impact on forest carbon stores compared to an intensive harvest regime.

Harvest and thinning do not reduce carbon emissions. Full accounting shows that thinning increases carbon emissions to the atmosphere for at least many decades.

Carbon returns to atmosphere more quickly when removed from forest and put in product chain.

1. Role of forest ecosystems in mitigating climate change – Carbon storage and accumulation

Allowing existing forests to accumulate carbon is likely to have a positive effect on forest carbon in vegetation and soils, and on atmospheric carbon. Wet forests in the PNW and Alaska have some of the highest carbon stocks and productivity in the world. Fires are infrequent in these forests, occurring at intervals of one to many centuries. Old forests store more carbon than young forests. Old forests store as much as 10 times the biomass carbon of young forests (Law et al. 2001, Hudiburg et al. 2009). The low hanging fruit is to allow these forests to continue to store and accumulate carbon.

A key objective is to reduce GHG emissions. Changes in management should consider the current forest carbon sink and losses in the product chain when evaluating management options.

2. Role of natural disturbance in forest carbon budgets

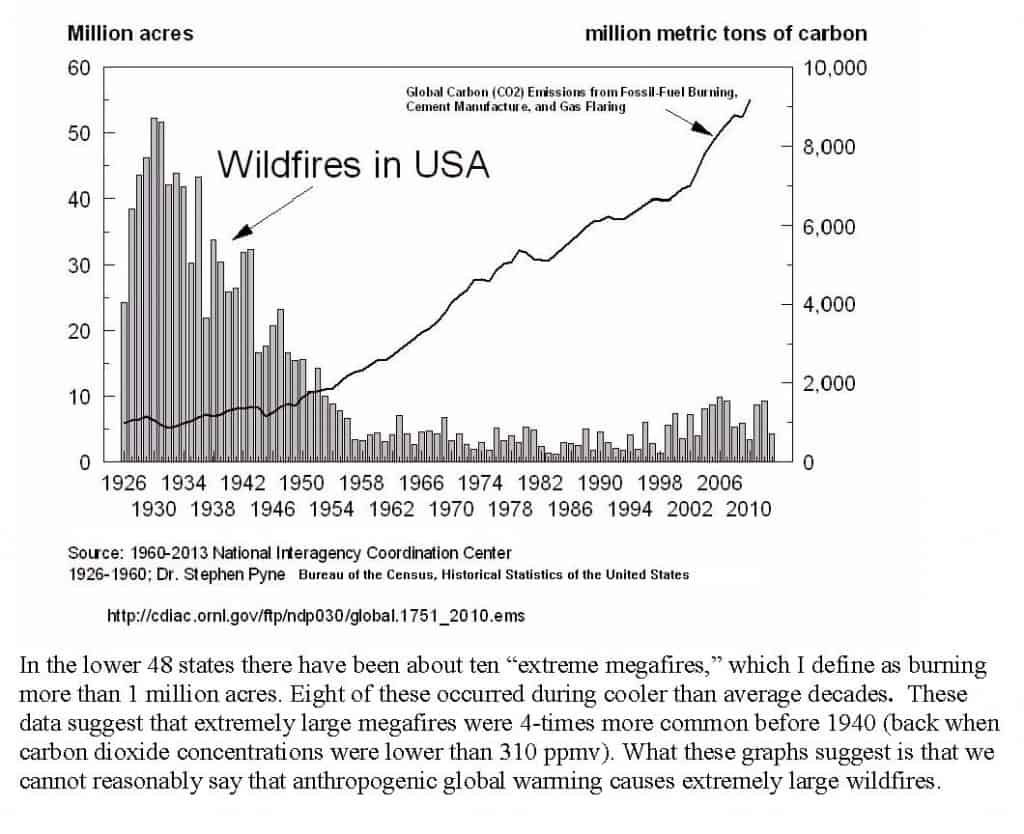

Natural disturbance from fire and insects has little impact on forest carbon and emissions compared with intensive harvest.

Although wildfire smoke looks impressive, less carbon is emitted than previously thought (Campbell et al. 2007). In PNW forests, less than 5% of tree bole carbon combusts in low and high severity fires (Campbell et al. 2007, Meigs et al. 2009). Most of what burns is fine fuels in low and high severity fires, making actual carbon loss much less than one might expect. For example, from 1987-2007, carbon emissions from fire were the equivalent of ~6% of fossil fuel emissions in the Northwest Forest Plan area (Turner et al. 2011). If fire hasn’t significantly reduced total carbon stored in forests, it isn’t going to materially worsen climate change.

In the western states, 5-20% of the burn area has been high severity fire and the remaining burn area has been low and moderate severity (MTBS; www.mtbs.gov). In the PNW, 50-75% of live biomass survived low and moderate severity fires combined, which account for 80% of the burn area (Meigs et al. 2009). Physiology measurements show that current methods used to determine if trees are likely to die post-fire lead to overestimation of mortality and removal of healthy trees (Irvine et al. 2007, Waring data in Oregon District Court summary). Removal of surviving trees from a burned area will reduce carbon storage, and in many cases regeneration.

The release of carbon through decomposition after fire occurs over a period of decades to centuries. About half of carbon produced by fires remains in soil for ~90 years, whereas the other half persists in soil for more than 1,000 years (Singh et al. 2012). Similarly, after insect attack and tree die-off, there isno large change in carbon stocks. Carbon stocks are dominated by soil and wood, and wood in trees that are killed transfers to dead pools that decompose over decades to centuries.

3. How do forest management strategies such as thinning affect carbon budgets on federal lands?

Forest carbon density could be enhanced by decreasing harvest intensity and increasing the intervals between harvests. For example, biomass carbon stocks in Oregon and N California could be theoretically twice as high if they were allowed to continue to accumulate carbon (Hudiburg et al. 2009). Even if current harvest rates were lengthened just 50 years, the biomass stocks could increase by 15%.

Harvest intensity – The Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) was enacted to conserve species that had been put at risk from extensive harvesting of old forests. Prior to enactment, the public forests were a source of carbon to the atmosphere. Harvest rates were reduced by ~80% on public lands, which led to a large carbon sink (increase in net ecosystem carbon balance, NECB) in the following decades. Direct losses of carbon from fire emissions were generally small relative to harvest (Turner et al. 2011, Krankina et al. 2012).

Thinning forests – Landscape and regional studies show that large-scale thinning to reduce the probability of crown fires and provide biomass for energy production does not reduce carbon emissions under current and future climate conditions (Hudiburg et al. 2011, Hudiburg et al. 2013; Law & Harmon 2011; Mitchell et al. 2009, 2012; Schulze et al. 2012; Mika & Keeton 2012). If implemented, it would result in long-term carbon emission to the atmosphere because many areas that are thinned won’t experience fire during the period of treatment effectiveness (10-20 yrs), and removals from areas that later burn may exceed the carbon ‘saved’ by reducing fire intensity (Law & Harmon 2011; Campbell et al 2012; Rhodes & Baker 2009). Thinning does not necessarily reduce fire occurrence, particularly in extreme weather conditions (drought, wind).

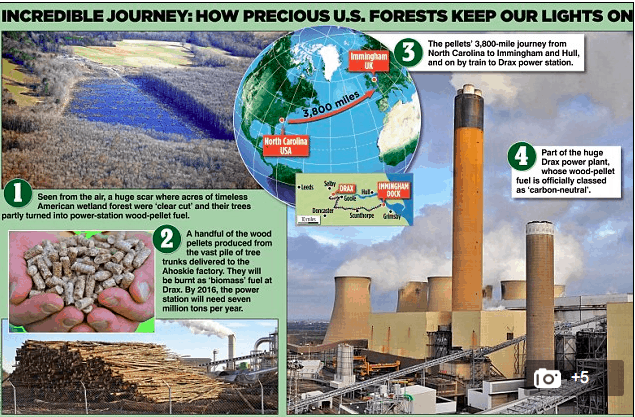

Slow in and fast out – opportunity cost. Today’s harvest is carbon that took decades to centuries to accumulate, and it returns to the atmosphere quickly through bioenergy use. Increased GHG emissions from bioenergy use are primarily due to consumption of the current forest carbon and from long-term reduction of the forest carbon stock that could have been sustained into the future. The general assumption that bioenergy combustion is carbon-neutral is not valid because it ignores emissions due to decreasing standing biomass that can last for centuries.

Bioenergy still puts carbon dioxide in the atmosphere when a key objective is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The global warming effect of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere does not depend on its source. Per unit of energy, the amount of carbon dioxide released from biomass combustion is about as high as that of coal and substantially larger than that of oil and natural gas (Haberl et al. 2012).

Summary

Comprehensive assessments are needed to understand the carbon consequences of land use actions, and should include a full accounting of the land-based carbon balance as well as carbon losses through the products chain. In mature forests, harvest for wood product removes ~75% of the wood carbon, and 30-50% of that is lost to the atmosphere in the manufacturing process, including the use of some of that carbon for biomass energy. The remainder ends up back in the atmosphere within ~90-150 years, and there are losses over time, not just at the end of the product use). These loss rates are much higher than that of forests. Full accounting of all carbon benefits, including crown fire risk reduction, storage in long- and short-term wood products, substitution for fossil fuel, and displacement of fossil fuel energy, shows that thinning results in increased atmospheric carbon emissions for at least many decades.