Some people might be getting tired of the PM 2.5 topic… and plus with current fire retardant issue, the idea that EPA – the agency that, as we have seen, can’t keep track of the money it’s spending, uses un-ground-truthed wildfire risk models developed by an NGO without any transparent government oversight.. doesn’t have enough employees to do what they are already tasked with.. and doesn’t play well with land management agencies. per GAO. And then there’s the perceived need to blame neighboring states for miniscule amounts of ozone pollution in Denver.

Nevertheless, I thought that this was a super article by reporter Danielle Venton of KQED. It is long and comprehensive, as befits a piece on such a complicated subject. I like the way she structured it.

1. Updating the standard is good, say public health, air regulators and the EJ community. According to a quoted source, it saves lives, especially those of communities of color.

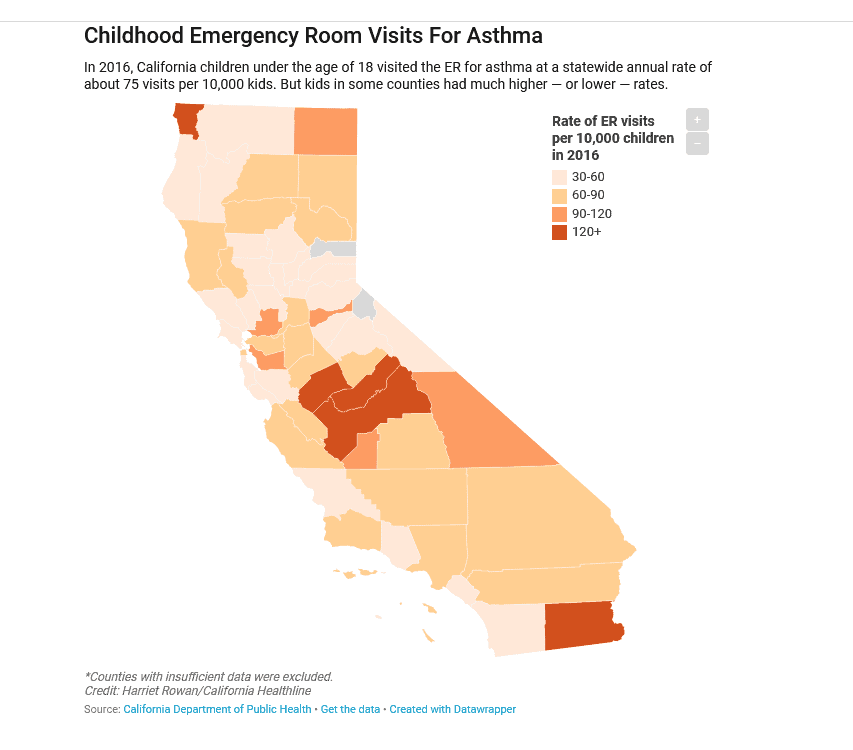

According to the story, it’s particularly a problem om Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley. As a former resident of Southern California, home of all income levels and races, I think it might be better to target specific producers of whatever pollutants are leading to increased asthma.

“Everyone knows a parent who has brought their baby, or their 2-year-old, into the ER because they couldn’t breathe. You know, the baby’s turning blue,” Amsalem said. “It’s a story you hear across generations.”

If you go to the linked article here, you find about the San Joaquin Valley

Because the region is surrounded on three sides by mountain ranges, pollutants get trapped in the valley. Wildfires — such as the blazes that have dirtied the valley’s air this summer — exacerbate asthma symptoms and send more kids to the emergency room.

Wildfires likely contributed to the high rate of childhood ER visits for asthma in Del Norte County in 2016 — 121 visits per 10,000 children — which represents an increase of more than 40 percent from the previous year. Del Norte, which sits along the Oregon border, had the fifth-highest rate in the state in 2016.

And if we look at the map, Imperial County has the problem of dust from the Salton Sea drying up. I’m not sure that wildfires or the Salton Sea will be helped by a new PM2.5 regulation.

2. Wildfires are bad for PM 2.5

It still amazes me that people never noticed this until wildfires were blamed on climate change. All those discussions in California about why wildfires are good.. and this didn’t come up until the last few years.

Today, with emissions from the worst pollutants down by more than 70% (PDF), the EPA estimates the Clean Air Act saves 230,000 lives annually and hundreds of thousands more from asthma, bronchitis and heart attacks. Public health experts estimate the benefits of all these lives saved and hospital visits avoided into the many trillions of dollars.

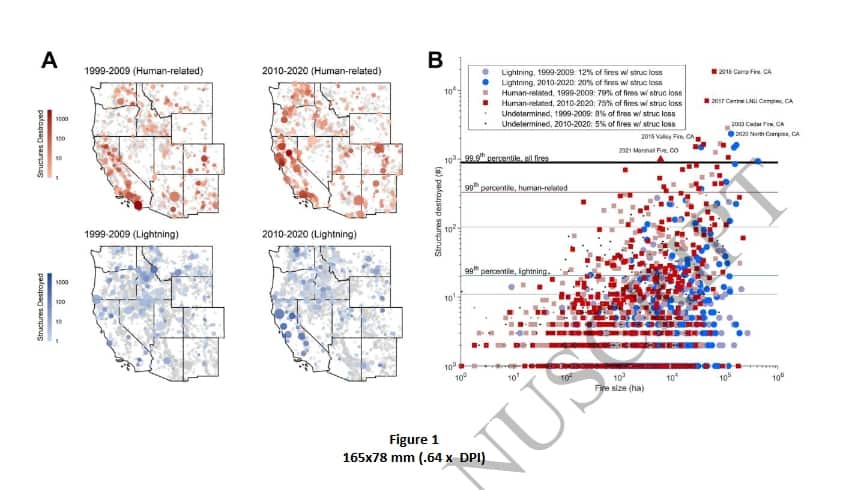

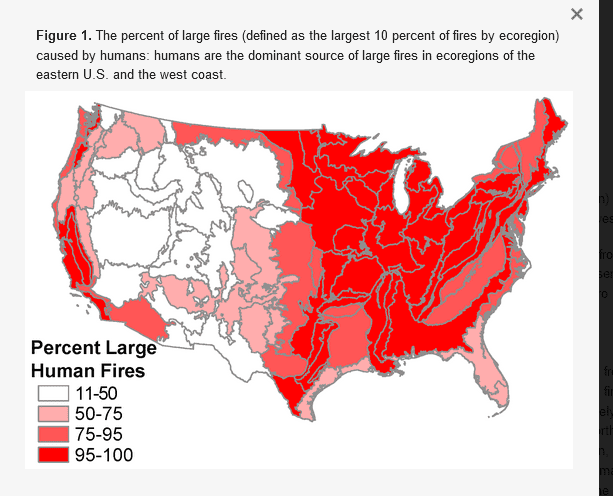

Wildfires are now a major producer of both carbon emissions and tiny specks of sooty pollutants known as PM 2.5. A 2022 study from the National Center for Atmospheric Research found that wildfire pollution was beginning to reverse decades of clean air gains. (Researchers at Stanford in 2020 had similar findings [PDF].)

******

The EPA estimates a third of the PM 2.5 we breathe in this country is from wildfires. For those in the West during wildfire season, it can be 90%.

And if wildfire trends continue and worsen, as climate models suggest they will, then we’ve seen nothing yet.

2. But to reduce wildfire smoke, we need to have prescribed fire (or burn excess fuels in some kind of smoke free environment, which seems possible, but not at the scale we’re talking about). And here’s a process the EPA has:

However, EPA officials recognize that sometimes air districts are out of compliance through no fault of their own. In this case, they are allowed to file for an “exceptional event.” In this bureaucratic process, the “event” is linked to the cause of pollution going over the legal limit. It is meant for events that are unforeseeable and are unlikely to occur in the same location again, like a volcanic explosion. If the link can be made, then emissions from that event can be subtracted from the total, and the air district is no longer in trouble with the EPA.

It is a long, technically involved process. A California Air Resources Board (CARB) exceptional events filing (PDF) for ozone concentrations during the Northern California wildfires of 2020 runs 228 pages.

You’re kidding me.. California taxpayers paid for CARB employees to write about ozone from forest fires? Isn’t there anyone who is interested in “useful and efficient” regulation rather than unclear and wasteful regulation?

The problem, as seen by many in the wildfire science community, is that while this process essentially means air districts are not on the hook for wildfire smoke, they are on the hook for prescribed fire smoke. And prescribed fire — the most affordable, effective inoculation against future wildfires — has never been used as a basis for an exceptional event in California.

*********

The EPA also seems aware of these concerns. In its proposed rule, it says it acknowledges stakeholder concerns about the importance of prescribed fire and intends to work with stakeholders to address these issues. It also says prescribed fires have the potential to qualify for exceptional events (PDF), which could encourage their continued and expanded use.

However, this has environmental lawyers very concerned. Sara Clark of the law firm Shute, Mihaly and Weinberger works with nonprofit organizations and supports prescribed fire and Indigenous cultural burners. She thinks the EPA’s reasoning as written might not hold up under a judge’s evaluation.

“[The EPA] does a lot of linguistic acrobatics to try and clarify how a prescribed fire is … not reasonably preventable or controllable. But it’s called a ‘controlled burn,’” said Clark. “I’m concerned about the legal underpinnings there.”

She also believes that the time and technical expertise needed to file for an exceptional event exemption would make air regulators wary of using it. Extensive documentation and analysis is needed to submit for an exceptional events determination from CARB or the EPA.

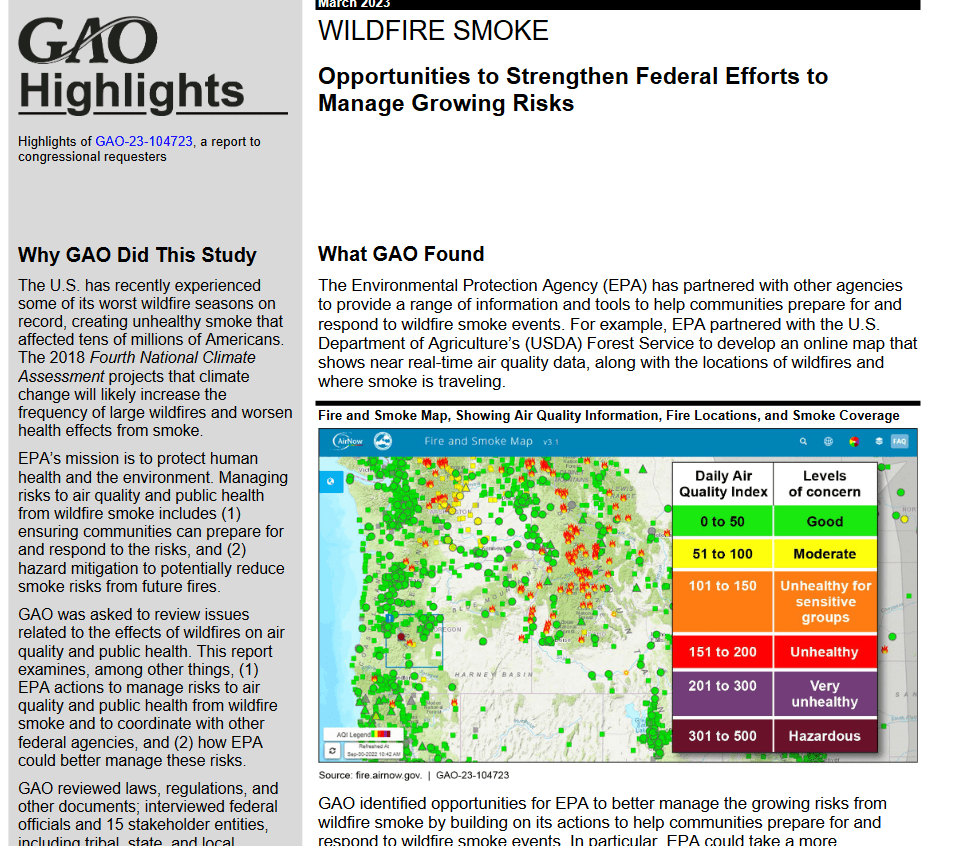

A recent Government Accountability Office report echoes these concerns. The report says the EPA could do a better job working with other agencies to reduce impacts from wildfires (PDF), including making it easier to conduct prescribed fires.

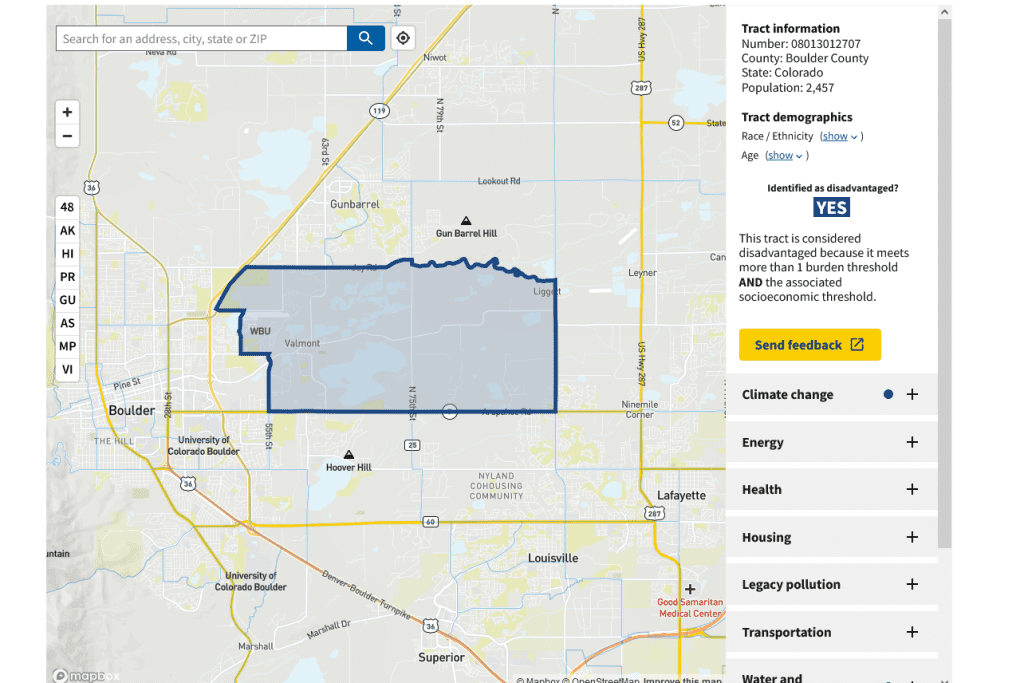

Stakeholders interviewed by the GAO said that state and local agencies aren’t likely to use the exceptional events provision for prescribed burns because “the agencies would not likely approve prescribed burns that could cause National Ambient Air Quality Standards exceedances in the first place.” And they said that “exceptional event demonstrations are technically complicated and resource intensive.”

Put another way, it’s more likely that prescribed burns would never happen if air regulators thought they might have to file for an exceptional event.

It is also legally uncharted, or nearly uncharted, territory. The EPA has received only one exceptional events demonstration for a prescribed burn (PDF) — too much ozone was associated with prescribed burns in the Flint Hills of Kansas in December 2012. But since then, no tribal, state or local agency has submitted an exceptional event demonstration for a prescribed burn, according to EPA officials.

The air districts (who need to keep EPA as much on their side as possible) aren’t worried

Neither Bay Area nor California air regulators seem to share the worries of the fire community that the EPA will hamper the increased use of prescribed fire, however.

She expressed hope that the rule’s implementation phase, which it now heads into, would be the time for nitty-gritty details to be worked out.

“Even though they can be expunged from the data, residents are still feeling [the effects of wildfire] very much so,” said Amsalem, of the Central California Environmental Justice Network. She hopes agencies will work out this issue, she said, “because we do need to do more prescribed burning to reduce the catastrophic events.”

It seems unlikely to me that an agency would willing give up fairly unconditional power over other agencies’ activities, but we’ll see how this all works out.