1) Can’t NFF already accept private donations for things? Didn’t know it was restricted.

2) In the distant past (1970’s) I recall a set of sequoia plantations in California in various places (known as Prof. Libby’s sequoia plantings). Did anyone ever round up what information might be available from them about reforestation? Are the trees still alive and measured?

WASHINGTON – Today, House Committee on Natural Resources Ranking Member Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.) joined House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), U.S. Reps. Scott Peters (D-Calif.), Jim Costa (D-Calif.), David Valadao (R-Calif.), Jimmy Panetta (D-Calif.), Tom McClintock (R-Calif.) and 23 other members in introducing H.R. 8168, the Save Our Sequoias (SOS) Act. That link wasn’t working, so here is the text until that one goes live.Save Our Sequoias Act

Background

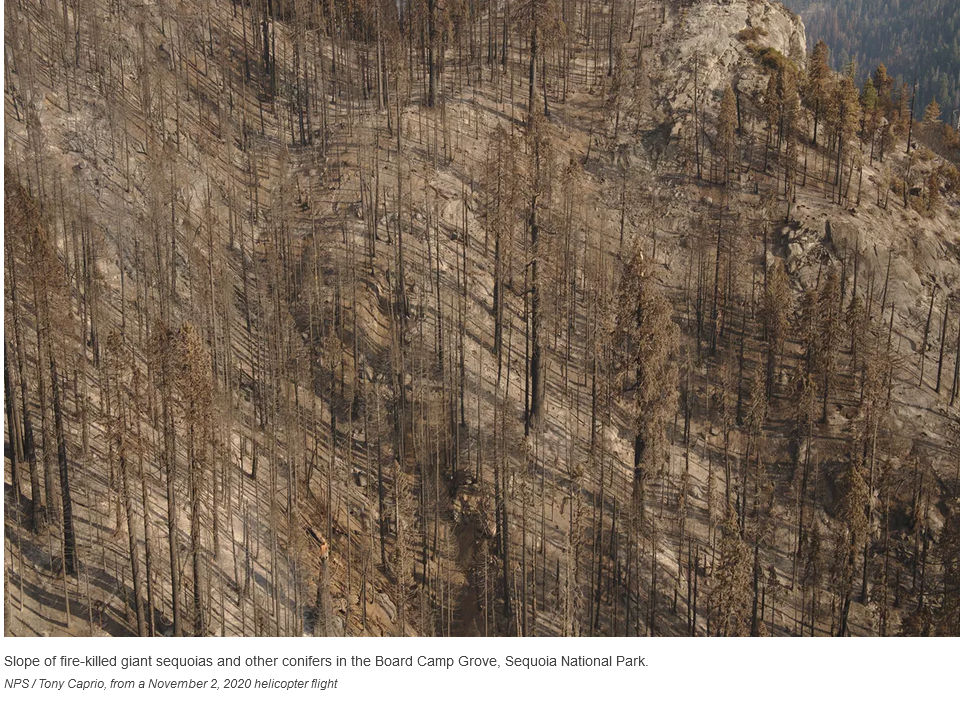

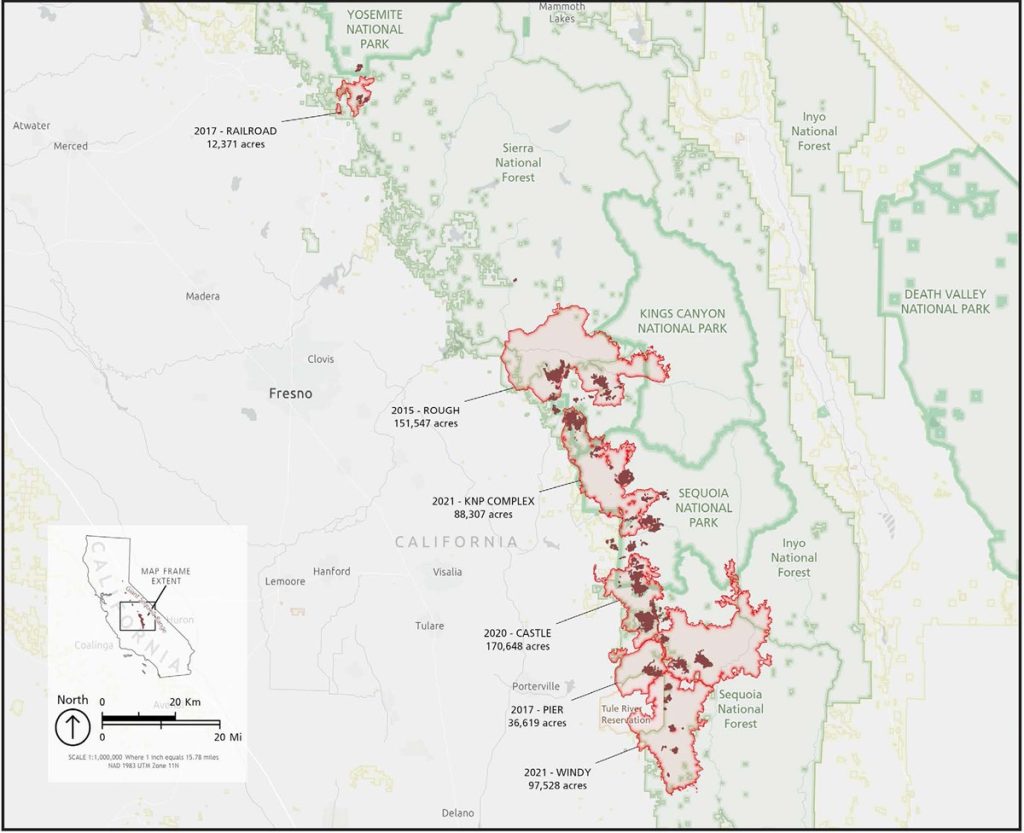

In the past two years alone, catastrophic wildfires wiped out nearly one-fifth of the world’s Giant Sequoias. Covering only 37,000 acres in California across roughly 70 groves, Giant Sequoias are among the most fire-resilient tree species on the planet and were once considered virtually indestructible. However, more than a century of fire suppression and mismanagement created a massive build-up of hazardous fuels in and around Giant Sequoia groves, leading to unnaturally intense, high-severity wildfires. The emergency now facing Giant Sequoias is unprecedented – the last recorded evidence of large-scale Giant Sequoia mortality due to wildfires occurred in the year 1297 A.D., more than seven centuries ago.

Despite the looming threat to the remaining Giant Sequoias, federal land managers have not been able to increase the pace and scale of treatments necessary to restore Giant Sequoia resiliency to wildfires, insects, and drought. At its current pace, it would take the U.S. Forest Service approximately 52 years to treat just their 19 highest priority Giant Sequoia groves at high-risk of experiencing devastating wildfires. Without urgent action, we are at risk of losing our iconic Giant Sequoias in the next several years. Accelerating scientific forest management practices will not only improve the health and resiliency of these thousand-year-old trees but also enhance air and water quality and protect critical habitat for important species like the Pacific Fisher.

The SOS Act will provide land managers with the emergency tools and resources needed to save these remaining ancient wonders from the unprecedented peril threatening their long-term survival. The bill would:

*Enhance coordination between federal, state, tribal and local land managers through shared stewardship agreements and the codification of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, a partnership between the current Giant Sequoia managers.

*Create a Giant Sequoia Health and Resiliency Assessment to prioritize wildfire risk reduction treatments in the highest-risk groves and track the progress of scientific forest management activities.

*Declare an emergency to streamline and expedite environmental reviews and consultations while maintaining robust scientific analysis.

*Provide new authority to the National Park Foundation and National Forest Foundation to accept private donations to facilitate Giant Sequoia restoration and resiliency.

*Establish a comprehensive reforestation strategy to regenerate Giant Sequoias in areas destroyed by recent catastrophic wildfires.

**

SOS Act original cosponsors: U.S. Reps. Scott Peters (D-Calif.), Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.), Jim Costa (D-Calif.), David Valadao (R-Calif.), Jimmy Panetta (D-Calif.), Tom McClintock (R-Calif.), John Garamendi (D-Calif.), G.T. Thompson (R-Penn.), Mike Thompson (D-Calif.), Ken Calvert (R-Calif.), Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.), Mike Garcia (R-Calif.), Lou Correa (D-Calif.), Doug LaMalfa (R-Calif.), Ami Bera (D-Calif.), Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.), Sanford Bishop (D-Ga.), Young Kim (R-Calif.), Ed Perlmutter (D-Colo.), Dan Newhouse (R-Wash.), Kurt Schrader (D-Ore.), John Curtis (R-Utah), Tom Malinowski (D-N.J.), Russ Fulcher (R-Idaho), Kaiali’i Kahele (D-Hawaii), Michelle Steel (R-Calif.), Juan Vargas (D-Calif.), Pete Stauber (R-Minn.) and Josh Gottheimer (D-N.J.).

More than 90 organizations support the SOS Act, including: ACRE Investment Management, American Conservation Coalition, American Forest & Paper Association, American Forest Foundation, American Forest Resource Council, American Loggers Council, American Sportfishing Association, American Wood Council, Aramark Parks & Destinations, Archery Trade Association, Associated California Loggers, Association of American Railroads, Association of California Water Agencies, Bipartisan Policy Center Action, Boone & Crockett Club, Calaveras Big Trees Association, Calaveras County Water District, Calaveras County, California Assemblyman Vince Fong, California Cattlemen’s Association, California Farm Bureau, California Forestry Association, California Senate President pro Tempore Toni Atkins, California Senator Shannon Grove, Carbon180, Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Charm Industrial, CHM Government Services, Citizens Climate Lobby, Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, ConservAmerica, Dallas Safari Club, Delek US Holdings, Drax, Ducks Unlimited, Edison International, Enviva, Evangelical Environmental Network, Federal Forest Resource Coalition, Forest Landowners Association, Forest Resources Association, Fresno County, Giant Sequoia National Monument Association, Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, Great Basin Institute, Hardwood Federation, Healthy Forests, Healthy Communities, Houston Safari Club, International Inbound Travel Association, International Paper, Inter-Tribal Timber Council, Kern County, Kern River Valley Chamber of Commerce, Kernville Chamber of Commerce, Mariposa County, National Alliance of Forest Owners, National Association of Counties, National Association of Forest Service Retirees, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, National Forest Recreation Association, National Wild Turkey Federation, Niskanen Center, Outdoor Industry Association, Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, PG&E, Placer County Water Agency, Placer County, Public Lands Council, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Rural County Representatives of California, Salesforce, Salt River Project, San Diego Gas & Electric, Save the Redwoods League, Sequoia Parks Conservancy, Sierra Forest Products, Sierra Pacific Industries, Society of American Foresters, Springville Chamber of Commerce, The Nature Conservancy, Trust for Public Land, Tulare County Farm Bureau, Tulare County Fire Department, Tulare County, Tule River Tribe, Tuolumne County, Vista Outdoor, Weyerhaeuser Company, Wildlife Management Institute, Yosemite Clean Energy, and Yosemite Conservancy.

It seems like they would like the committee to be a FACA committee, which seems reasonable and to have some kind of public involvement (I’m not sure that the Park Service and the Forest Service would actually propose a project without public involvement. They also argue that the NPS and FS have enough CEs to do the trick already.