I’d like to point out to any FS leadership who read TSW that folks on the Forest wouldn’t talk to me to tell their side of the story. So they are being good employees. Problem is, if it weren’t for retirees who happen to keep up with the details (retirees like this being rare and threatened by loss of interest), we would never hear the FS side- unless there is an objection response on the same points. Maybe this would be a good application for AI.. “find the FS statements about … in the EA, response to comments and objections.” Still, I don’t think the Cone of Litigation Silence is good for public understanding, trust and support.

Anyway, here’s a link to Jack Igelman’s recent article on the issue. You can follow him on TwitX @ashevillejack. I’m not a legal person, as everyone knows, so there are some quotes from me that are off the top of my head about why these 15 acres are of concern. Conceivably with the same funding invested, the plaintiffs could buy their own 15 acres and manage it however they wanted. Maybe our friends at SELC will weigh in. Kudos to Jack for reading the EA!

The agency is obligated to manage the forest along the Whitewater River as a wild and scenic river corridor, which limits management options. However, timber harvesting is allowed to occur as long as it does not harm the river’s outstandingly remarkable values or degrade its water quality. The wild and scenic corridor extends about one quarter-mile on each side of the river.

“This timber prescription takes it backwards,” said Nicole Hayler, executive director of the Chattooga Conservancy. “The Forest Service has a track record of management activities in eligible areas to basically whittle away at the eligibility.”

Will harvesting “harm the values” or “whittle away at eligibility”? I don’t think we can judge without the prescription. (NHP is the natural heritage program.)

In the Southside Project’s final Environmental Analysis released in 2019, the Forest Service included a response to objections that the project analysis failed to analyze impacts to state natural areas.

The NHP determined that portions of the stand are dominated by white pine, an artifact of previous land use that is not naturally occurring.

According to the NHP, “It would be beneficial to remove the white pines from this stand, and then manage the area after harvest in such a way to restore the natural community” while acknowledging that some areas along the Whitewater River are in excellent condition.

The NHP did not respond to CPP’s interview request.

But if it’s good to remove the white pines, then maybe taking some more trees and getting openings for the “natural community” is a good idea. Again, it would be nice to see the prescription.

The timber harvest prescriptions for the tract “require harvesting much more than white pine,” SELC attorney Patrick Hunter said. “We can say with certainty that the NHP’s request to limit logging to white pine is not reflected in the Forest Service’s final decision.”

But did the NHP say to limit the logging to WP? What other species are there? Is taking out the WP and other species an opportunity to increase tree species diversity or wildlife habitat?

Although the lawsuit includes a relatively small parcel of land, Friedman said that the court’s ruling could establish legal precedent around the influence of new forest plans on projects initiated and authorized under prior plans.

“The same groups who didn’t want certain projects before will still not want them” after a forest plan is finalized, she said. “If they feel strongly enough about them and have the financial wherewithal, they will litigate those projects. That’s just the way it works for most of the country; it’s business as usual. “

Litigating forest restoration projects in the Forest Service’s Southern region, however, are less frequent compared to other parts of the country, such as the Northern or Pacific Southwest region. There has been just one forest restoration project litigated in the Southern region which stretches from Texas to Virginia since 2003.

Hunter told CPP this is the first time SELC has initiated litigation against the Nantahala or Pisgah National Forest.

Whether the case is settled inside or outside of court, Friedman said changing an existing agency decision may set a precedent for other projects and other national forests.

According to Hunter of the SELC, the lawsuit seeks to validate the understanding that activities occurring within the national forest must be consistent with the current forest plan.

He noted that the complaint could reinforce existing precedent citing a 2006 decision against the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee in which the court ruled that a timber harvesting and road building project must be made consistent with a revised forest management plan that went into effect after the projects’ authorization.

The legal action reflects broader concerns about balancing the need for timber harvesting to restore the ecology of the forest while preserving ecologically significant areas and underscores the complexities of managing public lands.

*************

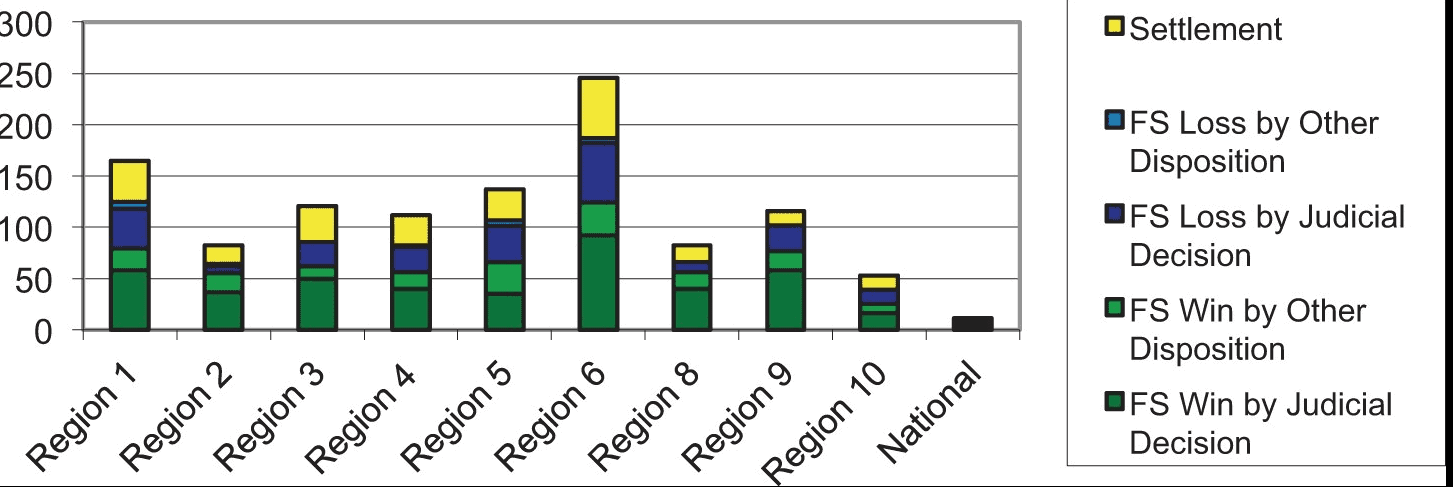

Of course, the Cherokee NF is indeed in Region 8, so I guess the difference is whether the project is a “restoration” project or a “logging” project. I would only offer that what the FS sees as a restoration project (with tree removal), other entities often see as a “logging” project. This is a real side trip- but I ran across a paper by Miner et al. from 10 years ago (no paywall) that had this graph. The authors characterized these as “land management” cases, not necessarily vegetation management cases.

*******

David Whitmire, of the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Council, which represents the interests of fishers and hunters in Western North Carolina, said the lawsuit could, however, slow down forest-restoration work.

“I would rather see money spent on projects rather than lawyers,” Whitmire said. “The Forest Service is having to back up and deal with the lawsuit. It takes away a lot of resources that would otherwise benefit the forest.”

I’d only add that if this case sets precedent for forest plans being retroactive for ongoing previously approved projects, I think it might have two effects: first that Forests will not want to do plan revisions. When I worked in Region 2, many forests were not enthused about plan revisions anyway (reopening large numbers of disagreements to what end?). Second is that if they are in revision, they would seemingly be less inclined to give areas with ongoing projects more restrictive designations. It seems that both of these co-evolutionary responses by the FS would be against what plaintiffs would ultimately prefer.

But perhaps the plaintiffs will weigh in.